暗香盈袖

如鹰展翅 更新茁壮我一直对戴德生很好奇 . 他说 : “ 假如我有千镑英金,中国可以全数支取;假如我有千条生命,决不留下一条不给中国 ” 。 一个十九世纪的英国人 , 为什么会到中国来 , 又怎么会把自己打扮成中国人的模样 , 是什么令他确信要 把自己的一生 , 以及子孙都献给中国 ? 他是怎样走上这样一条路的 ?

有一天我在一本书 ( 这本书这一章节讲的是蒙神呼召的人常常要做出牺牲 , 更常常令他们的亲人做出更大的牺牲 ) 里读到戴德生自己回忆的 , 乘船去中国宣教时在码头与母亲分别的一幕 , 我的眼眶湿了 , 感到了他们那一刻的刺痛 . 更加定意要读一读他的经历 .

( 为了方便不懂英文的朋友 , 我把引用的文字翻成中文 , 原文附在文章后面 .)

"戴德生 , 一个伟大的 , 有信心 , 靠祷告的人 , 蒙神呼召去中国传道 . 因为他的父亲已去世 , 他得与他寡居的母亲分离 . 在 1905 年他去世之前 , 他为神所用 , 在中国内地传教 . 当时在内地有了 205 个传教点 ,849 名传教士 ,125,000 中国基督徒 – 一个生命完全降服于神的见证 . 戴德生描述了他和母亲为了顺服上帝的旨意 , 去中国传教所付出的代价 .

把你自己想象成戴德生,你的父亲已去世,你意识到可能有生之年再也见不到母亲了.仔细阅读他记录的和母亲的离别 , 试着想象他们的感受 :

‘ 我挚爱的 , 现已为圣徒的母亲到利物浦来送我 . 我永远也不会忘记那一天 , 以及她和我一起走进那间小小舱房的情景 , 在那儿我将住上漫长的六个月 . 她用一双充满母爱的手帮我整理了小床 . 她坐在我身边 , 和我一起唱最后一首赞美诗 , 之后我们就将长时间地分离了 . 我们跪下来 , 她为我祷告 , 是我出发去中国之前最后听到的母亲的祷告 . 然后 , 我们被告知必须离别了 , 我们得相互告别 , 在世上我们不能期待再见 .

为了我 , 她尽量控制自己的感情 . 我们分开了 ; 她上了岸 , 仍在为我祝福 ! 我独自站在甲板上 , 船开向码头大门时 , 她跟着我们跑 , 我永远忘不了从我母亲心底发出的痛彻心扉的哭喊 . 它如尖刀一般刺穿了我的心 . 在此之前 , 我从来没有真正懂得 ” 神如此深爱世人 ” 的意思 . 而我确信我亲爱的母亲在此刻比以往一生都更理解神对正走向灭亡的世人的爱 .

赞美主 , 更多的人正在发现这超乎想象的喜乐 , 神奇妙恩典的显现 , 是赐给那些 ” 跟随他 ”, 将自己献上 , 完全顺服在他伟大旨意里的人 .’”

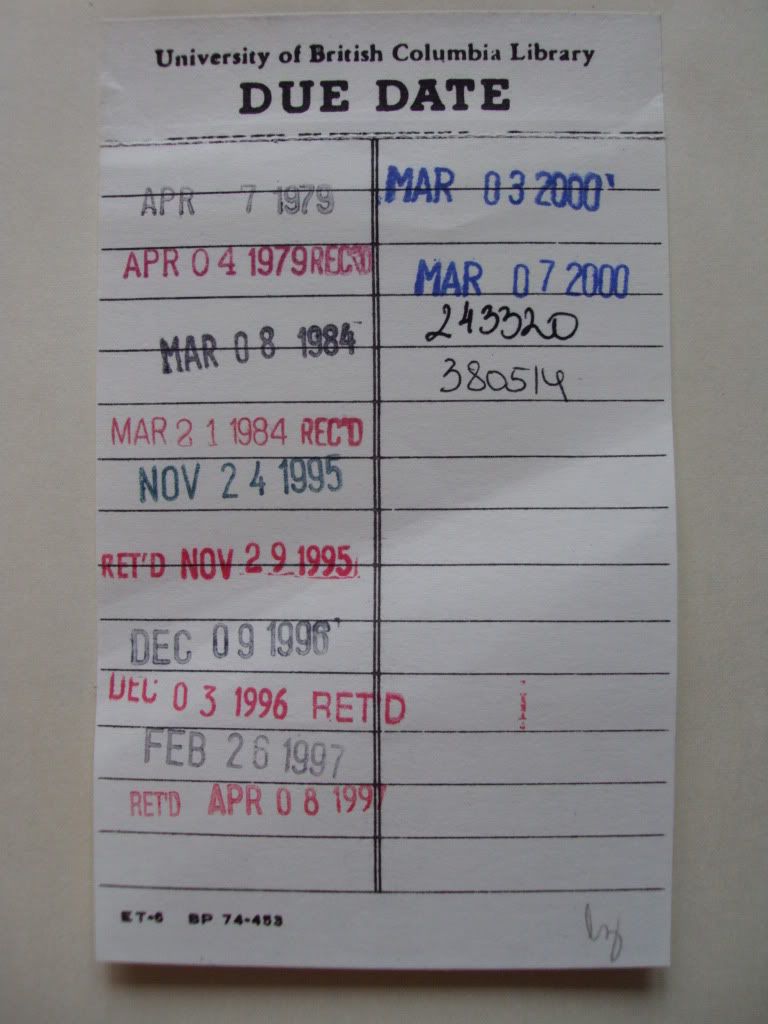

温哥华图书馆里居然很难找到他的传记 , 经过内部借调 , 才从卑诗省大学图书馆弄来了这本 < 戴德生和玛利亚 >( Hudson Taylor and Maria -By J.C.Pollock). 很旧的一本书 , 出版于 1962 年 , 彼时我还没有出世 . 这本书常年呆在书架上 , 有着老书特有的陈旧 , 脆弱 , 以及真正的书香 . 上一次它被人握在手里 , 是十一年前 .

里面的事情发生得更早 , 它们令我如此感动 .

书里记载了戴德生在英格兰约克郡的青少年时代 , 以及他在中国传福音 , 在神的带领下成长 , 生儿育女 , 直到他妻子玛利亚去世的经历 .

1832 年戴德生出生在一个基督教家庭 , 但他对于福音并没有真正的认识 . 他没有上大学 , 不喜欢家里浓厚的宗教氛围 , 十五岁时去了一家银行做事 , 他为人诚恳 , 热情 , 乐观 , 很得人缘 , 在那里他慢慢远离了神 , 活在这世界的欲望里 , 常常说些亵渎神的话 .1848 年他回到他父亲店里打杂 .

“ 他身体不好 , 过早的性发育 , 灵魂里不满足的折磨使他烦躁不安 , 容易沮丧 , 变得乖戾 .

一年以后 ,1849 年的六月 , 他母亲出门了 . 一个暖和的下午艾美利亚 ( 他妹妹 ) 也出去了 . 戴德生有半天假 , 无所事事 . 他懒洋洋地翻着父亲的书 , 在一篮子流行的 ” 福音小册子 ” 里拿出一本 , 想着读一下故事 , 然后跳过后面的道德说教 . 他去了房子和店后面的谷仓 , 舒舒服服蜷缩着 ,’ 毫不不在意地开始读书 , 心里的意图很清楚 , 只要书的内容一开始变得单调乏味就把它丢开 .’

正读着 , 一句话抓住了他的心 . 忽然间他明白了他理解宗教的角度错了 . 他相信基督教教义是一场沉闷枯燥的用做好事来为坏事抵债的挣扎 . 如此他早就破产了 , 仅用去教会礼拜和晚上草草的祷告来向他神圣的造物主付一点点账 , 完全没有偿清债务的可能 . 就像很多破产的人一样 , 他只想今朝有酒今朝醉 .

可书里的一句话令他豁然开朗 , 突然确信耶稣在十字架上受死 , 已经为他偿清了所有罪的债 .’ 这如破晓一般欢喜的确认 , 如光一般瞬间由圣灵照进我的灵魂 . 原来在这世上除了跪下 , 接受我的救主及其救恩 , 永远赞美他之外 , 我并不需要做什么来得到救赎 .’

马丁路德 , 约翰班杨 , 约翰卫斯理都不会比戴德生在 1849 年那个六月的下午 , , 他十七岁时更完全地感受到 : 重担被卸去 , 光驱除了黑暗 , 以及重生并和耶稣建立了亲密的友情 .

几天过去了 , 他害羞地向艾美利亚说出了秘密 . 十天后 , 他母亲回来时他飞奔到门口 ’ 告诉她我有这样一个好消息要宣布 .’ 母亲拥抱了他 ,’ 我知道 , 我的儿 , 两周来我一直在欢喜庆祝你要告诉我的这个大喜事 .’ 戴德生太吃惊了 . 是不是艾美利亚多嘴了 ? 他母亲说不是的 . 她说 , 在 80 英里以外 , 就在谷仓发生事情的那一天 , 她感到一种铺天盖地无以阻挡的愿望要为戴德生祷告 , 于是她跪在地上数小时为他祷告 , 起来时心里有不可撼动的确信 , 那就是她的祷告已经被应许 . ‘ 也许这正是自然的 ,’ 戴德生很多年以后写道 ,’ 从我基督徒生活的一开始 , 我就被引导着感受到 , 祷告原是和神之间交流的严肃事情 .’

待续

另外推荐,戴德生自传 : <献身中华>中文版 http://www.docin.com/p-82704447.html

原文

Experiencing God

Hudson Taylor, a great man of prayer and faith, responded to God's call to go to China as a missionary. Because his father had already died, he had to leave his widowed mother to go to China. By the end of his life in 1905, he had been used by God to found the China Inland Mission. There were 205 preaching stations, 849 missionaries, and 125,000 Chinese Christians -- a testimony of a life absolutely surrendered to God. Hudson Taylor described something of the cost he and his mother experienced as he obeyed God's will to go to China as a missionary.

Imagine that you are Hudson Taylor. Your father is dead, and you realize that you may never see your mother again on earth. Slowly read Taylor's account of their parting and try to imagine the emotions they must have felt.

My beloved, now sainted, mother had come to see me off from Liverpool. Never shall I forget that day, nor how she went with me into the little cabin that was to be my home for nearly six long months. With a mother's loving hand she smoothed the little bed. She sat by my side, and joined me in the last hymn that we should sing together before the long parting. We knelt down, and she prayed--the last mother's prayer I was to hear before starting for China. Then notice was given that we must separate, and we had to say good-bye, never expecting to meet on earth again.

For my sake she restrained her feelings as much as possible. We parted; and she went on shore, giving me her blessing! I stood alone on deck, and she followed the ship as we moved towards the dock gates. As we passed through the gates, and the separation really commenced, I shall never forget the cry of anguish wrung from the mother's heart. It went through me like a knife. I never knew so fully, until then, what "God so loved the world" meant. And I am quite sure that my precious mother learned more of the love of God to the perishing in that hour than in all her life before.

Praise god, the number is increasing who are finding out the exceeding joys, the wondrous revelations of His mercies, vouchsafed to those who "follow Him," and emptying themselves, leave all in obedience to His great commission.

Hudson Taylor and Maria

By J.C.Pollock

With adolescence Hudson grew restless with the religious atmosphere of home. At fifteen he entered a local bank where, being merry and gay , he was popular, and “used to wish for money and a fine horse and house, and I longed to go hunting as some did who were about me.” The other clerks brushed his mind free of religion. He scoffed and swore, probably mildly, for he was sensitive and did not relish his mother’s resigned glances or Amelia’s tears; besides, his father beat him for blasphemy.

The gaslight in the murk of a Yorkshire winter was too much for Hudson’s eyes; they were weak for the rest of his life. He left the bank in 1848 to serve the jars and bottles of his father’s shop, prescribing for bunions of famers’ wives in to market, mixing powders when the mayor’s offspring had colic. Ill health, early sexual development and gnawing dissatisfaction of soul made him fidgety and unsettled, easily upset and cross.

A year later, in June 1849, his mother was away. One warm afternoon Amelia was out and Hudson had nothing to do on a half-holiday. He looked idly over his father’s books and rummaged in a basket of popular “Gospel tracts.”He picked one out, intending to read the story and skip the moral He went into the barn behind the hose and shop, curled up comfortably and began “in an utterly unconcerned state of mind, with a distinct intention to put away the tract as soon as it should seem prosy.”

As he read, one sentence gripped him. Suddenly he realized that he approached religion from the wrong angle. He believed Christianity to be a dreary struggle to pay off bad deeds by good. He had long bankruptcy, paying a small dividend to his Divine Creator in the shape of chapel attendance and prayers rattled off at night but with no hope of discharge; like most bankrupts he had sought to have a good time.

One sentence in the tract broke open his mind to a sudden certainty that Christ by His death upon the cross had already discharged the debt of sins. “And with this dawned the joyful conviction, as light was flashed into my soul by the Holy Spirit, that there was nothing in the world to be done but to fall down on one’s knees and accepting this Saviour and His Salvation, to praise Him forevermore.”

No Luther, Bunyan or Wesley had a more complete sense of the rolling away of his burden, of light dismissing darkness, of rebirth and the close friendship of Christ, than Hudson Taylor on that June afternoon of 1849, at the age of seventeen.

Several days passed before he shyly to d Amelia under seal of secrecy. At the return of his mother ten days afterwards he ran to the door “to tell her I had such glad news to give.” She replied as she hugged him, “I know, my boy. I have been rejoicing for a fortnight in the glad tidings you have to tell me.” Hudson was amazed. Had Amelia blabbed? His mother denied it. She said that 80 miles away, on the very day of the incident in the barn, she had felt such overwhelming desire to pray for Hudson that she spent hours on her knees and had arisen with unshakable conviction that her prayers were answered. “It was perhaps natural,” Taylor wrote years later, “that from the commencement of my Christian life I was led to feel that prayer was in sober matter of fact transacting business with God.”