India Ready For 'Any Contingency' Against China, Warns Head Of Army

Amid heightened tensions between neighboring Asian powers that are home to the world's two largest populations, India has grown closer to the United States and other Western-aligned nations, while becoming increasingly wary of a rising China.

But even as New Delhi takes unprecedented steps toward shoring up relations with the Washington, there appears to be little chance the traditionally non-aligned nation will establish any formal defense alliance with the U.S.

"In fact, we do refer to India and the USA as natural allies," former Indian ambassador to China Ashok Kantha told Newsweek, "but this is not in the sense of a military alliance."

Such an alliance would run contrary to more than 75 years of India's post-colonial history after winning its independence from the United Kingdom and suffering a violent partition with Pakistan, sparking the first of several wars over disputed territory with the neighboring Islamic Republic as well as one with China six decades ago. Even during some of the nation's most dire crises, however, India has opted to not choose sides among world powers.

"We had to suffer a period of colonial subjugation lasting two centuries, and then we emerged as one of the most populous countries in the world, which was also innovative in democracy, in multiculturalism and in an open society," Kantha said. "We came to the conclusion during the Cold War period that India cannot be a camp follower of either great power, at that time the USA and the Soviet Union, that we will work with both countries."

Today, this policy referred to by India as "strategic autonomy" continues amid growing frictions between the U.S. and China, even if New Delhi saw Washington as the better partner.

"We will not be equidistant, we will take positions on issues," he added. "On some issues we might be closer to the USA, but we will not join a military alliance. And this basic consensus has remained unchanged."

In this Newsweek photo illustration, U.S. President Joe Biden and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi shake hands during the G20 Summit on November 15, 2022 in Nusa Dua, Indonesia.

Such a position has never implied neutrality. Throughout the Cold War, New Delhi forged a tight strategic partnership with Moscow, a relationship still very much alive today in the form of diplomatic interactions and the outsized presence of Russian weaponry comprising the arsenal of the Indian Armed Forces.

So, while Kantha asserted that India had "serious misgivings" regarding Russia's decision to launch a war in Ukraine in February of last year, he said "we abstain from condemning Russia because it's a relationship that has been historically important to us, and even today for a variety of reasons."

Even before the conflict in Ukraine, however, Kantha said that New Delhi was looking to diversify its military partnerships, a trend that has served as a major opportunity for U.S.-India relations, in which he said that "defense is emerging as a very major area." In addition to a broadening array of intelligence-sharing pacts, the two countries have pursued a growing number of joint exercises, including the Yudh Abhyas training that took place in November near India's disputed border with China.

The contested 2,100-mile boundary separating China and India, known as the Line of Actual Control, has been the source of the most serious tensions between the two powers in decades, beginning with a deadly series of clashes in 2020. The two sides have repeatedly attempted to de-escalate the situation, but tense encounters and skirmishes have continued among troops armed with clubs and stones.

After the latest publicly acknowledged clash that occurred in December, U.S. News & World Report cited unnamed sources claiming that the U.S. offered India real-time intelligence support throughout the incident.

Kantha, who was personally involved in navigating China-India diplomacy during his tenure as ambassador, said Beijing's actions in recent years "caused deep pain or anxieties and misgivings in India, as also in the USA."

"So while India is definitely not inclined to move towards any kind of containment of China, we believe that a country like China cannot be contained, or nor are we interested in the economic decoupling from China," Kantha said, "I think we are more inclined towards some kind of de-risking strategy vis-à-vis China, we are inclined to build deterrence to guard against China's reckless behavior to avoid a repetition of what happened along the borders in the western sector in April and May 2020."

The task at hand for India, according to Kantha, "will largely be building our own capabilities, but also requires an aspect of external balancing of China and then working together with USA and other likeminded countries will become, and is already in fact, an important component of our policy."

And while he was skeptical of any major improvement in China-India relations without serious progress made on the border dispute, he said avoiding a more serious conflict was crucial for India to achieve its national goals on other fronts.

"It's extremely important, because our defense budget remains relatively modest and we would like to focus on development for the foreseeable future," Kantha said. "Getting distracted by any conflict or protracted escalation of tensions along the borders is definitely not in our interest."

Indian army soldiers stand guard outside their bunker on the Srinagar-Leh highway on January 6 in Zojila, 67 miles east of Srinagar in Indian-administered Kashmir. The strategic pass connects Kashmir with Ladakh, which is located.

Swaran Singh, a visiting professor at the University of British Columbia with decades of experience lecturing at India's major diplomatic and military institutions, also argued that managing this relationship was essential for achieving the long-term objectives of both powers.

"De-escalation is the only way as both China and India cannot afford to derail their development trajectories and miss their imagined historic resurgence to the center stage of world affairs," Singh told Newsweek. "But as two rapidly growing economies and peer civilizational states reclaiming their place under the sun, their competition remains inevitable."

The dynamic between China and India was not always so grim. While their 1960s border war, China's close ties with Pakistan and India's hosting of the separatist government-in-exile of Tibet following the region's annexation by China in the 1950s fostered deep-rooted bitterness between the two powers, efforts began in the late 1980s and early 1990s to rehabilitate their relations and, as recently as 2018 and 2019 Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi held summits in their respective countries.

Their fatal border spat three years ago, just as COVID-19 began to grip the world, signaled a dark turn, however. The feud has continued to make headlines as the Indian Foreign Ministry rejected China's decision last week to rename 11 places within territory claimed by India and the Chinese Foreign Ministry criticized Indian Home Minister Amit Shah's visit to the contested frontier region on Monday.

And yet, with border tensions still simmering, Singh asserted that "both sides agree on the need to begin a new chapter of confidence building to suit their new avatar as rapidly developing major powers."

At the same time, he said "both also continue with heavy forward deployments while also working on military disengagement which has been, even in face of regular core commander level and inter-ministerial meetings, patchy and uneven."

"As they learnt to deal with their bilateral and historic problems," Singh said, "they now need to learn ropes of engaging each other in their new avatars as major powers and especially in their interface in regional and global fora."

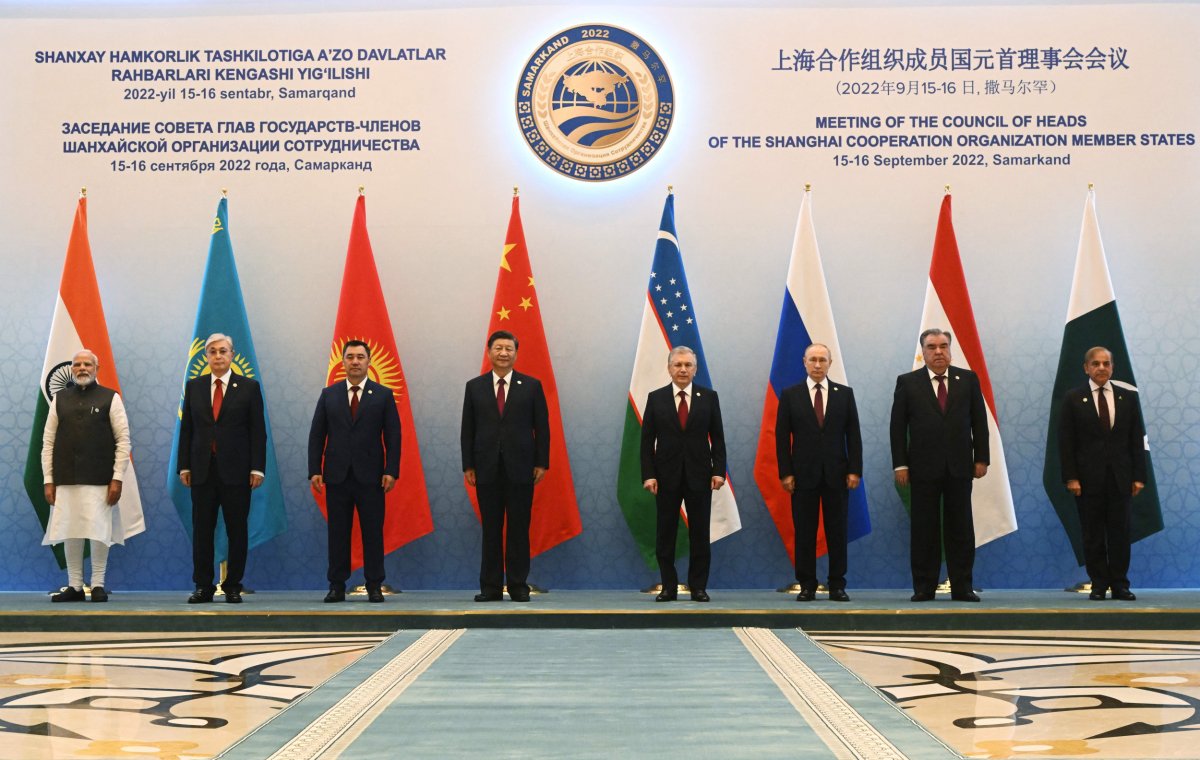

The two countries have managed to share at least some common ground in certain key venues gaining more relevance in an increasingly multipolar international order. These include the nine-state Shanghai Cooperation Organization bloc and the informal coalition known as BRICS, in which China and India are joined by Brazil, Russia and South Africa.

READ MORE

This election may give China a new Latin America friend at Taiwan's expense

What two Taiwan trips mean for fate of most dangerous U.S.-China issue

Four years from brink of war, can Pakistan in crisis avoid new India clash?

A number of other countries have applied to or expressed interest in joining these two groups that promise to put bilateral quarrels aside in the interest of greater security and economic coordination.

Still, China's growing clout in the economic, military and diplomatic spheres have presented both risk and opportunity for New Delhi.

"While China has demonstrated an unprecedented economic growth that undergirds its political influence and military modernization, China's rise has made India the preferred partner for status quo powers in the U.S.-led liberal world order," Singh said. "This has opened doors for technology transfers and defense cooperation for India, making India the only neighbor that has showcased capacity to stand up to China."

India has also doubled down on its participation in another multilateral group, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, commonly known as the Quad, alongside the U.S., Australia and Japan. The quartet has intensified cooperation among members and it is regularly accused by China of representing an attempt to form a bloc built on containing the People's Republic.

But, like Kantha, Singh pointed out that there were limits to these ties built into India's core tenets as a nation.

"Even at its weakest moment of independence with partition, India chose nonalignment that defines its civilizational DNA," Singh said. "Today, as the world's largest population country, third-largest defense spender, fifth-largest economy and a state with nuclear weapons, this sentiment stands reinforced and reflected in its axiom of multialignment."

He also argued that the same instability in the world order that has made room for growing roles for both China and India has also helped to prevent the two sides from effectively catering to their ailing bilateral relations.

"Pandemic and the Ukraine war have surely distracted both China and India from attending to their bilateral problems, if not further complicated China-India equations," Singh said. "So, while a more peaceful world may avail them opportunities to redress some of their irritants, some amount of brinkmanship will continue to define China-India relations."

(L-R) Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Kazakhstan's President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Kyrgyzstan President Sadyr Japarov, Chinese President Xi Jinping, Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Russian President Vladimir Putin, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon and Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz.

Happymon Jacob, an associate professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University and founder of the Council for Strategic and Defense Research in New Delhi, pointed to another important factor in the complex dynamic of China-India relations.

While the U.S. surpassed China as India's top trading partner last year, the People's Republic remains an influential economic player. As such, Jacob told Newsweek that there is "an absence of a consensus in India on openly calling out Chinese aggression, which is primarily a result of India's economic relationship with China."

Fundamentally, however, he too saw the ongoing dispute over territory as primarily driving the downturn in China-India relations.

"The reason behind the deterioration in Sino-Indian relationship is China's land grab strategy on the border with India," Jacob said. "China is also unhappy about India's growing partnership with the U.S., which (at least partly) is a result of China's aggression in the first place."

"If China were to reinstate the territorial status quo as it existed prior to the summer standoff of 2020 and stake no more claims to Indian territories, it is possible to deescalate bilateral tensions," he added. "But I don't think China is keen to do that."

Given the level of mistrust that has been fostered among the two sides, Manoj Joshi, a fellow at the New Delhi-based Observer Research Foundation who has served in national security advisory roles in India, also told Newsweek that "the chances of a rapprochement are low."

"The two countries have been very careful in ensuring that things don't go from bad to worse, but there seems to be no meeting ground on which a new modus vivendi can rest," Joshi said. "De-escalation can be worked out and is, in fact, being worked out. But rapprochement is unlikely. Suspicions will not go away easily."

"The situation will remain fraught, especially since both sides continue to build up their forces on either side of the Line of Actual Control that marks their border," he added. "The earlier process had rested on agreements that had sought to build down such forces."

But obstacles exist to India's growing proximity to the U.S. as well. While the perceived threat from Beijing has helped fuel New Delhi's shift toward Washington, there are a host of other geopolitical issues on which India and the U.S. are at odds.

"The power gap between India and China, is certainly a major factor driving the current convergence of U.S.-India ties," Joshi said. "But India's positions are mainly driven by its size and interests. It perceives a significant security threat from Pakistan, whereas the U.S. has been at various times a major military ally of Pakistan. And where it sees Iran as a relatively benign actor in the Persian Gulf and a friend, the U.S. has seen Tehran as a hostile player."

"This rules out the possibility of a formal military alliance with the U.S.," Joshi said, "something that would require a much closer identity of views."