风萧萧_Frank

以文会友全球经济进入动荡时代

https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2023-geopolitical-investments-economic-shift/

中美紧张局势和乌克兰战争已经将投资转向志同道合的国家——这表明企业正在进行地缘政治赌注。

作者:肖恩·唐南和恩达·柯兰

Maeva Cousin 的数据和分析

制图:Jennah Haque,2023 年 9 月 18 日

在一些全球最大的公司的财报电话会议和公司文件中,这个词越来越多地出现。 从贝莱德等华尔街巨头,到可口可乐、特斯拉等消费巨头,以及 3M 公司等工业支柱,标普 500 强企业的首席执行官及其副手在 2023 年使用“地缘政治”一词近 12,000 次,或者 几乎是两年前的三倍。

这不仅仅是说说而已。 现在出现的确凿证据表明,所有关于紧张国际关系的讨论以及十多年来对全球化时代结束的警告最终促使企业选择其资本的立场。 多年来,西方跨国公司一直回避地缘政治,转而在不太成熟的市场中追求利润,它们越来越多地在志同道合的国家建设未来工厂。

当世界领导人本周齐聚纽约参加年度联合国大会时,彭博经济研究对联合国外国直接投资数据的分析表明,世界正在重组为相互竞争的集团(尽管仍然相互联系),这反映了联合国对俄罗斯入侵美国的投票结果。 乌克兰。 分析发现,在 2022 年投资的 1.2 万亿美元绿地外国直接投资中,有近 1,800 亿美元跨地缘政治集团从拒绝谴责俄罗斯入侵的国家转移到那些谴责俄罗斯入侵的国家。

“这是一个历史性的变化,”韩国前贸易部长杨汉九 (Yeo Han-koo) 表示,他认为世界正在进入一个动荡的时代。 “新的经济秩序正在形成,这将带来不确定性和不可预测性。”

联合国大会投票谴责俄罗斯入侵的国家占全球GDP的三分之二以上。 摄影师:Angela Weiss/法新社/盖蒂图片社

这种转变的促进因素是显而易见的。 饱受疫情影响的政府正在敦促企业牢记国家利益,并提供补贴和其他激励措施,作为将生产带回国内的诱饵。 俄罗斯入侵乌克兰以及美中竞争加剧,加速了贸易和全球化蓬勃发展的冷战后脆弱模式的终结。

令政策制定者担忧的潜在成本和后果也是如此。 欧洲央行行长克里斯蒂娜·拉加德今年早些时候以异常直接的语言宣称,“我们正在目睹全球经济分裂成相互竞争的集团,每个集团都试图让世界其他国家更接近各自的战略利益” 和共同的价值观。”

世界对俄罗斯乌克兰战争仍存在分歧。2023年联合国投票要求俄罗斯从乌克兰撤军

注:地图显示了出席诉讼程序的不同联合国成员的投票情况。来源:联合国

这种焦虑是有充分理由的。 国际货币基金组织 (International Monetary Fund) 经济学家今年早些时候计算出,在最极端的情况下,即全球经济分裂为硬派,从长远来看,将摧毁多达 7% 的产出,这一转变类似于消灭法国和法国。 他们确定,德国经济。

需要明确的是,这次突破既不平衡也不干净。 以美国和德国等欧盟大国为首,投票谴责俄罗斯入侵的国家占全球国内生产总值的三分之二以上。 中国位于另一个集团的核心,其超越美国经济作为世界主导经济体的竞赛正受到经济增长放缓的打击,许多人认为这反映了长期问题。

快速了解:“朋友支持”对贸易的未来意味着什么

即使世界上出现了新的经济铁幕,它也是一个漏洞百出的铁幕。 如今,全球经济比以往任何时候都更加一体化,而且它们之间的关系也很复杂。 乌克兰战争和由此产生的制裁扰乱了特定商品的贸易,而美中贸易战等其他事件也造成了自身的破坏,但现实是全球商业一直具有弹性。

分裂的世界经济的未来

资料来源:国际货币基金组织、世界银行、彭博经济研究

企业追逐利润和利润丰厚的市场的本能与消费者对便宜货的渴望一样强烈,使得这个新时代持久地具有交易性。 正如美国商务部长吉娜·雷蒙多(Gina Raimondo)上个月访问中国时所表明的那样,这两个集团的成员仍然渴望相互出售产品,并将恢复波音公司飞机和其他美国出口产品的销售列为她的首要议程。

中国电动汽车公司正在竞相进入欧洲,尽管他们的这样做引发了欧盟对中国补贴的调查。

美国商务部长吉娜·雷蒙多 (Gina Raimondo) 表示,正如美国商务部长吉娜·雷蒙多 (Gina Raimondo) 上个月访问中国时所展示的那样,中美两国的成员仍然热衷于向对方出售波音飞机和其他美国出口产品。 摄影师:沉其来/彭博社

印度等国家在联合国投票中投了弃权票,选择不谴责俄罗斯的入侵,但它们正在寻求与美国和其他西方大国建立新的战略关系,这些国家认为这些联系至关重要。 中国和西方投资者都在涌入越南和墨西哥等日益重要的互联经济体大家庭,这些经济体正试图跨越联合国投票双方的阵营。

但迄今为止,大转变的主要轶事证据正在强化,没有任何数据点比绿地外国直接投资(对新工厂的长期投资往往需要数年时间才能实现和指出)更能说明世界正在发生的变化。 公司对未来做出的大赌注。

彭博经济研究利用谴责俄罗斯入侵乌克兰的联合国投票作为过滤器,发现过去两年流向不谴责俄罗斯入侵乌克兰的国家的绿地外国直接投资的全球份额平均仅为 15%,低于 2019 年的 30%。 截至 2019 年的十年。中国(包括香港)的份额从 2010-19 年的平均近 11% 降至 2022 年的不足 2%。 对俄罗斯的投资完全枯竭。

数据表明,美国和其他西方公司在志同道合的国家进行了更多投资。 美国是 2021-22 年的最大赢家,与疫情爆发前的十年相比,其在全球绿地外国直接投资中所占份额增幅最大。 彭博经济分析发现,德国、意大利甚至英国等其他七国集团国家在外国投资中的份额也在增加。

没有谴责俄罗斯的国家减少了外国直接投资的流入

按目的地划分的绿地外国直接投资价值,以 2010-2019 年平均水平为指数

资料来源:联合国贸易和发展会议、彭博经济研究

除其他因素外,这可能反映出美国产业政策的转变,鼓励对半导体和电动汽车等战略行业进行更多投资,以及日本、韩国和台湾等欧洲和亚洲盟友的反应。

但这也标志着另一种非凡的转变。

尽管世界贸易组织本月表示,现在宣布全球化时代结束还为时过早,但它警告说,地缘政治紧张局势正开始影响贸易流动,而且碎片化的早期迹象正在出现。 世贸组织估计,自乌克兰入侵以来,两个假设的地缘政治集团之间的货物贸易增长速度比这些集团内部的贸易增速慢 4% 至 6%(根据联合国的投票模式)。

国际货币基金组织经济学家今年早些时候宣称,投资和商品流动不再遵循通常的路径。 曾经利润丰厚的新市场的承诺占据主导地位,国际货币基金组织对二十年数据的研究发现,近年来,地缘政治在推动资本流动方面发挥了加速作用。

国际货币基金组织研究部副主任安德里亚·普雷斯比特罗表示:“即使你控制了国家风险和地理距离等通常是双边贸易和资金流动的关键驱动因素的因素,你仍然会发现地缘政治问题。” “近年来,地缘政治因素似乎更为重要。”

鉴于其作为世界最大贸易国的地位,大部分转变都围绕着中国。 国际货币基金组织向彭博社分享的最新分析显示,与疫情爆发前的五年相比,2020年第二季度至今年第一季度,美国公司在中国的绿地投资下降了57.9%,欧洲公司的绿地投资下降了36.7% 。 亚洲其他地区对中国的投资下降了三分之二以上。

世界在中国以外寻找未来工厂。 疫情爆发以来对华外商直接投资与五年前相比

*新兴欧洲包括阿尔巴尼亚、白俄罗斯、波斯尼亚和黑塞哥维那、保加利亚、匈牙利、科索沃、摩尔多瓦、黑山、北马其顿、波兰、罗马尼亚、俄罗斯、塞尔维亚、土耳其和乌克兰。资料来源:国际货币基金组织

这一变化的背后是投资决策中日益重要的因素,即国际货币基金组织经济学家和其他人所说的“地缘政治距离”。 国际货币基金组织的经济学家利用基于七十年联合国投票的指数发现,最近的外国直接投资流量更有可能流向地缘政治一致的国家,而不是地理位置接近的国家。

国际货币基金组织的行动反映了经济学家正在发生的更广泛的演变。

几代人以来,经济学家一直通过依赖企业追求回报最大化的模型来观察全球经济,并根据地理影响或大国引力进行调整。 现在,他们正试图应对在数据驱动的经济世界中地缘政治中看似无形的力量以及政府定义国家安全的不断扩大的方式。

在外国直接投资中,地缘政治因素胜过地理因素。 地理位置或地缘政治邻近国家之间的全球外国直接投资年度份额

对于国际货币基金组织前首席经济学家、现任彼得森国际经济研究所高级研究员莫里斯·奥布斯特菲尔德来说,这真正意味着经济学家正在消化几个世纪以来权力竞争驱动贸易的历史常态的回归。 “历史的弧线不一定会向自由市场倾斜,”奥布斯特菲尔德说。

前世界银行首席经济学家、贸易和全球化领域的顶尖专家彭妮·戈德堡 (Penny Goldberg) 将地缘政治称为“人为的不确定性”。

引导美国和其他西方经济体政府进行变革的很大程度上是一种感觉,即他们的领导人长期以来错误地相信市场有能力做出正确的决定。 戈德伯格担心的是,世界可能在另一个方向上走得太远了。

她说,以国家安全而不是经济为指导力量进行投资往往需要更多地基于信任而不是数据。 戈德伯格说,历史上许多政府都有以安全名义做出错误判断的记录,比如 2003 年的伊拉克战争。 如果地缘政治正在推动投资,“你就必须相信政府的话。 有时,即使是善意的人也可能会犯错。”

戈德堡等人认为,日益扩大的分裂会给全球经济带来更广泛的负面影响。 其中包括随着制造成本上升而导致的通货膨胀加剧、由于国际研究合作变得越来越稀少而导致创新减少、随着对贫穷国家的投资停滞而加剧贫困和全球不平等。 志同道合的富国相互投资意味着对可能更需要投资的穷国的投资减少。

虽然迄今为止的地缘政治竞争往往集中在半导体或量子计算等战略技术领域,以及太阳能电池板、电池工厂和电动汽车工厂等新能源项目,但发展中的分歧也更广泛。

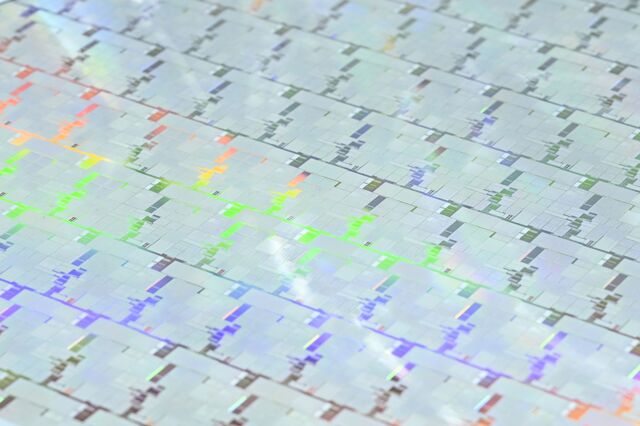

半导体迄今为止,地缘政治竞争往往集中在半导体等战略技术领域。 摄影师:Edwin Koo/彭博社

世界大宗商品贸易正在破裂。 这一切都始于能源、石油和天然气,但美国及其亚洲和欧洲盟友正在争先恐后地为矿物和其他原材料(如铜、镍和锂)建立新的友好供应链,这些原材料对生产半导体、手机和电动汽车至关重要。

全球半导体和可再生能源投资猛增。 已宣布的绿地外国直接投资项目的价值

资料来源:联合国贸易和发展会议

在一些地方,这种分歧是由摆脱美元的愿望推动的。 金砖国家正在探索一种新的共同货币,可能会保护成员国免受像对俄罗斯那样的制裁的影响。 孟加拉国已同意向俄罗斯支付约3亿人民币建设核电站的费用。 巴基斯坦热衷于达成以人民币购买俄罗斯原油的长期协议。

政府也比以前更愿意公开展示自己的力量。

在今年早些时候发布的一项新战略中,德国政府宣称其最大的“企业必须在决策时充分考虑地缘政治风险”。 它还警告企业,如果有一天它们面临与地缘政治危机相关的成本,则不应指望政府来救助它们。

中国总理李强发出的另一条信息同样直言不讳:他利用德国之行敦促首席执行官们自己做出投资决定,而不是屈从于政府。

人们很容易认为,这次下滑都是从唐纳德·特朗普 (Donald Trump) 2016 年当选开始的。但甚至在他或其他民粹主义者崛起之前,新经济集团的推动就已经开始了。 奥巴马政府与欧盟和亚太国家发起了地缘政治驱动的贸易谈判,但最终被特朗普扼杀。 中国自己推行的耗资9000亿美元的“一带一路”倡议从一开始就带有赤裸裸的地缘政治色彩,该倡议横跨亚洲并深入非洲。

可能出现的情况也比通常采用的冷战类比所暗示的更为复杂。

中国在许多供应链中仍然占据主导地位,甚至正在建设的新工厂也可能在未来几年至少使用一些中国投入。 荣鼎集团的分析发现,随着企业积极将投资和采购从中国转移出去,即使大幅转移到其他地点也可能只会导致中国的地位小幅下降,因为中国在全球制造业中占据主导地位。

奥布斯特菲尔德指出,同样,许多与中国有关系的新兴经济体仍然渴望西方投资。 许多人不想被迫在竞争对手的联盟之间做出选择。

金砖国家可能会通过增加沙特阿拉伯等新成员来扩大规模,但这个集团仍然因自身的地缘政治竞争而四分五裂,中国国家主席习近平决定缺席本月在印度举行的二十国集团会议就证明了这一点。

北京自己的联盟建设也出现了其他问题。 意大利已发出退出“一带一路”倡议的计划。 就在南非金砖国家峰会取得胜利几天后,印度和沙特阿拉伯与美国和欧盟一起公布了一项在南亚、中东和欧洲之间建立贸易和运输联系的计划。

2001年,高盛集团的经济学家吉姆·奥尼尔首次创造了“金砖四国”一词来强调新兴经济体的新俱乐部,他称这种划分是不切实际的,是“政治人物和一些理想主义者的炒作”。

“即使你看看那些在出口方面最有经验或最成功的国家,例如德国、韩国,他们也非常小心,避免过度受制于某个集团或另一个集团,”他说。

然而,我们很难忽视新出现的数据。 企业将赌注押在地缘政治上,并产生了后果。 野村证券(Nomura)经济学家在本月的一份报告中表示,中国在亚洲出口中所占的份额正在以至少二十年来最快的速度下降,部分原因是贸易正在多元化。 墨西哥最近取代中国成为美国最大的贸易伙伴。

阅读更多:美国最大的贸易伙伴不再是中国

贝莱德董事长拉里·芬克(Larry Fink)在该公司 7 月份的财报电话会议上宣称,“分散的地缘政治格局”是影响回报的新“结构性”力量,这种情况将持续下去。 即使是最反传统的首席执行官也在为新世界做准备。 在 7 月份与特斯拉投资者举行的电话会议中,埃隆·马斯克提出了他应对地缘政治崛起的解决方案:“我们能做的最好的事情就是在世界许多地方拥有工厂,”马斯克说。 “如果世界某个地方的事情变得困难,我们仍然可以让其他地方的事情继续下去。”

The Global Economy Enters an Era of Upheaval

https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2023-geopolitical-investments-economic-shift/

US-China tensions and the war in Ukraine are already swinging investments to like-minded countries — a sign that companies are making geopolitical bets.

by Shawn Donnan and Enda Curran

Data and Analysis by Maeva Cousin

Graphics by Jennah Haque,

One word has been popping up increasingly on earnings calls and in corporate filings of some of the world's biggest companies. From Wall Street giants like BlackRock Inc. to consumer titans like Coca-Cola Co. and Tesla Inc. and industrial mainstays like 3M Co., S&P 500 chief executives and their lieutenants have used the word “geopolitics” almost 12,000 times in 2023, or almost three times as much as they did just two years ago.

It’s not just talk. Hard evidence is now emerging that all the discussions of strained international relations and more than a decade of warnings over the end of an era of globalization are finally spurring corporations to pick sides with their capital. Western multinationals that for years have avoided geopolitics in favor of pursuing profits in less mature markets are increasingly building the factories of the future in like-minded nations.

As the world’s leaders gather in New York this week for the annual United Nations General Assembly, a Bloomberg Economics analysis of UN foreign-direct investment data points to a world reorganizing into rival — though still linked — blocs that reflect UN votes on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Of the $1.2 trillion in greenfield FDI invested in 2022, close to $180 billion shifted across geopolitical blocs from countries that declined to condemn Russia's invasion to those that did, the analysis found.

“This is a historic change,” said Yeo Han-koo, a former South Korean trade minister, who sees a world entering an era of upheaval. “A new economic order is being formulated and that will cause uncertainty and unpredictability.”

Countries that have voted to condemn Russia’s invasion account for more than two-thirds of global GDP. Photographer: Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images

Countries that have voted to condemn Russia’s invasion account for more than two-thirds of global GDP. Photographer: Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images

The accelerants for the shift are obvious. Pandemic-scarred governments are pressing companies to keep national interests in mind and providing subsidies and other incentives as a carrot to bring production home. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a building US-China rivalry have hastened the end of a fragile post-Cold War model that saw trade and globalization boom.

So too are the potential costs and consequences that are worrying policymakers. In unusually direct language, European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde declared earlier this year that “we are witnessing a fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs, with each bloc trying to pull as much of the rest of the world closer to its respective strategic interests and shared values.”

World Remains Split Over Russia’s War in Ukraine。 2023 United Nations vote calling for Russia to withdraw from Ukraine

Note: Map shows votes for distinct UN members that were present for the proceeding.Source: United Nations

There's a good reason for the angst. Economists at the International Monetary Fund earlier this year calculated that in the most extreme scenarios in which the global economy divides into hard blocs it would destroy as much as 7% of output in the long term, a shift akin to wiping out both the French and German economies, they determined.

To be clear, the break is neither balanced nor clean. Led by the US and European Union powers like Germany, countries that have voted to condemn Russia’s invasion account for more than two-thirds of global gross domestic product. China sits at the core of the other bloc and its race to overtake the US economy as the world’s dominant one is being hit by a slowdown in growth that many see reflecting longer-term problems.

Even if there is a new economic Iron Curtain descending on the world, it is a remarkably porous one. The globe’s economies are more integrated today than they have ever been and their relationships are complicated. The war in Ukraine and resulting sanctions have snarled trade in particular commodities and other events like the US-China trade wars have caused their own disruptions, but the reality is that global commerce has been resilient.

The Future of a Divided World Economy

Sources: IMF, World Bank, Bloomberg Economics

The instinct of corporations to chase profits and lucrative markets remains as strong as consumers’ desire for bargains, making this new era enduringly transactional. Members of either bloc remain eager to sell to each other, as US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo demonstrated last month when she traveled to China with a possible resumption of sales of Boeing Co. aircraft and other US exports high on her agenda. Chinese electric vehicle companies are racing into Europe, though their doing so has triggered an EU investigation into Chinese subsidies.

Members of both blocs remain eager to sell to each other, as US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo demonstrated last month when she traveled to China with sales of Boeing Co. aircraft and other US exports high on her agenda. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Members of both blocs remain eager to sell to each other, as US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo demonstrated last month when she traveled to China with sales of Boeing Co. aircraft and other US exports high on her agenda. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Countries like India that have chosen not to condemn Russia’s invasion, by abstaining in UN votes, are seeking new strategic relationships with the US and other Western powers, which see those links as vital. Both Chinese and Western investors are pouring into an increasingly important family of connecting economies like Vietnam and Mexico, which are trying to straddle the blocs on either side of UN votes.

But what was until now largely anecdotal evidence of a grand shift is hardening and no data point illustrates the way the world is changing more than what is happening in greenfield FDI — the long-term investments in new factories that often take years to realize and point to the big bets being made by companies on the future.

Using UN votes to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a filter, Bloomberg Economics found that the global share of greenfield foreign direct investment going to countries that didn't condemn the invasion averaged only 15% in the last two years, down from 30% in the decade to 2019. China's share, including Hong Kong, fell to less than 2% in 2022 from nearly 11% on average over 2010-19. Investment in Russia completely dried up.

The data point to US and other Western companies investing more in like-minded countries. The US was the biggest winner in 2021-22, seeing the largest increase in its share of global greenfield FDI versus the decade leading up to the pandemic. But also gaining share in foreign investment have been other Group of Seven countries like Germany, Italy and even the UK, the Bloomberg Economics analysis found.

Countries That Didn't Condemn Russia Trail FDI Flows

Value of greenfield foreign direct investment by destination, indexed to 2010–2019 average

Sources: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Bloomberg Economics

That may reflect, among other drivers, a shift in US industrial policy to encourage more investment in strategic sectors like semiconductors and electric vehicles, and the response from European and Asian allies like Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

But it also marks a remarkable pivot of another kind.

While the World Trade Organization this month said it’s premature to call an end to the era of globalization, it warned that geopolitical tensions are beginning to shape trade flows and that early signs of fragmentation are appearing. Goods trade between two hypothetical geopolitical blocs — based on voting patterns at the UN — have grown 4% to 6% slower than trade within these blocs since the invasion of Ukraine, the WTO estimates.

IMF economists earlier this year declared that flows of investment and goods were no longer following the usual paths. Where once the promise of lucrative new markets held sway, an IMF look at two decades of data found that the role of geopolitics had played an accelerating role in driving the flow of capital in recent years.

“Even if you control for features like country risk and geographic distance which generally is a key driver of bilateral trade and financial flows, you still find the geopolitics matters,” says Andrea Presbitero, deputy head of the IMF’s research division. And "geopolitical factors seem to matter more in recent years.”

Given its status as the world’s biggest trading nation, much of the shift revolves around China. Between the second quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of this year, US companies’ greenfield investments in China plunged 57.9% and those by European firms dropped 36.7% versus the five years leading up to the pandemic, an updated IMF analysis shared with Bloomberg found. Investments from the rest of Asia into China were down by more than two-thirds.

World Looks Beyond China for Factories of the Future. Foreign direct investment in China since the pandemic started, compared to the five years prior

*Emerging Europe includes Albania, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Hungary, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine.Source: International Monetary Fund

Behind the change is the growing importance in investment decisions of what the IMF economists and others have dubbed “geopolitical distance.” Using an index built on seven decades of UN votes, the IMF economists found that recent FDI flows had become more likely to go to geopolitically aligned countries rather than even geographically close ones.

The IMF exercise reflected a broader evolution underway among economists. For generations economists have peered out at the global economy through models reliant on the corporate drive to maximize returns, adjusted for the influence of geography or the gravitational pull of large countries. Now they are trying to deal with what in the data-driven world of economics feels like an amorphous force in geopolitics and the ever-expanding way governments define national security.

Geopolitics Edges Out Geography in Foreign Direct Investment. Annual share of global FDI between countries that are geographically or geopolitically close

Source: International Monetary Fund

To Maurice Obstfeld, a former IMF chief economist who is now a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, what that really means is that economists are digesting a return to what for centuries was a historical norm in which the power competition drove trade. “It's not necessarily true that the arc of history bends toward the free market,” Obstfeld says.

Penny Goldberg, a former World Bank chief economist who is also a leading expert on trade and globalization, calls geopolitics “manmade uncertainty.”

Much of what is guiding the change by governments in the US and other Western economies is a feeling that for too long their leaders had a misplaced belief in the power of markets to make the right decision. What worries Goldberg is that the world may be going too far in the other direction.

Making investments with national security rather than economics as a guiding force often entails acting more on trust than data, she says. Plenty of governments in history have a track record of making miscalculations in the name of security, like the 2003 war in Iraq, Goldberg says. If geopolitics is driving investment “you have to take the government at its word. And sometimes even well-meaning people may get it wrong.”

Goldberg is among those who see broader negative consequences for the global economy from a growing split. Those include higher inflation as the cost of manufacturing rises, less innovation as international research cooperation becomes rarer and more poverty and global inequality as investment in poor countries stalls. Like-minded rich countries investing in each other means less investment for poor countries that arguably need it more.

While the geopolitical competition so far has often been focused on strategic technology sectors like semiconductors or quantum computing, as well as new-energy projects like solar panel and battery plants and electric vehicle factories, the developing split is broader too.

Geopolitical competition so far has often been focused on strategic technology sectors like semiconductors. Photographer: Edwin Koo/Bloomberg

Geopolitical competition so far has often been focused on strategic technology sectors like semiconductors. Photographer: Edwin Koo/Bloomberg

The world’s commodities trade is fracturing. It all starts with energy and oil and gas, but the US and its Asian and European allies are scrambling to secure new friendly supply chains for the minerals and other raw ingredients like copper, nickel and lithium vital to produce semiconductors, phones and EVs.

Global Investment Soars in Semiconductors, Renewables. Value of announced greenfield FDI projects

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

In some places the division is driven by a desire to move away from the dollar. BRICS nations are exploring a new shared currency that might shield members from the impact of sanctions like those imposed on Russia. Bangladesh has agreed to pay Russia about $300 million in Chinese yuan for a nuclear power plant. Pakistan is keen for a long-term deal to buy Russian crude in the Chinese currency.

Governments are also much more comfortable showing their hand publicly than they once were.

In a new strategy released earlier this year, Germany’s government declared that its biggest “companies must take geopolitical risks sufficiently into account in their decision making.” It also warned companies that they shouldn’t count on the government to bail them out if they one day faced costs associated with a geopolitical crisis.

A competing message from Chinese Premier Li Qiang was equally blunt: he used a trip to Germany to urge CEOs to make their own investment decisions rather than bend to their government.

It’s tempting to believe this slide all began with Donald Trump’s election in 2016. But the push toward new economic blocs was underway even before his rise or that of other populists. The Obama administration launched geopolitics-motivated trade negotiations with the EU and Asia-Pacific countries that Trump eventually killed. China’s own pursuit of its $900 billion Belt and Road Initiative that reached across Asia and into Africa was nakedly geopolitical from the beginning.

What’s likely to emerge is also more complicated than the usually-deployed Cold War analogy implies.

China still has a dominant role in many supply chains and even the new factories being built are likely to use at least some Chinese inputs for years to come. Analysis by the Rhodium Group found that as companies actively diversify investment and sourcing away from China, even substantial shifts to alternative locations may only result in small declines in China’s role because of its dominance in global manufacturing.

Equally, many emerging economies that have relationships with China still hanker for Western investment, Obstfeld points out. And many don’t want to be forced to choose between rival alliances.

The BRICS may be expanding by adding new members like Saudi Arabia but it’s a bloc still riven with its own geopolitical rivalries as demonstrated by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s decision to skip this months’ G-20 meetings in India.

Beijing’s own alliance-building is showing other cracks. Italy has signaled its plans to exit the Belt and Road Initiative. Just days after what was billed as a triumphant BRICS summit in South Africa, India and Saudi Arabia joined with the US and EU to unveil a plan to build trade and transport links between South Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

Economist Jim O’Neill, who was at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in 2001 when he first coined the term BRIC to highlight a new club of emerging economies, calls a divide into blocs unrealistic and “hype from political figures and some idealists.”

“Even if you look at the countries who are the most experienced or successful in terms of exporting, for example Germany, South Korea, they are very careful about becoming too beholden to one group or another,” he said.

And yet it’s hard to ignore the emerging data. Companies are betting on geopolitics and it’s having consequences. China’s share of Asian exports is losing ground at the fastest pace in at least two decades in part because trade is diversifying, economists at Nomura said in a report this month. Mexico recently overtook China as the US’s top trading partner.

The “fragmented geopolitical landscape” that BlackRock Chairman Larry Fink declared as a new “structural” force shaping returns on the firm’s July earnings call is here to stay. And even the most iconoclastic CEOs are preparing for a new world. In his own July call with Tesla investors, Elon Musk offered his solution to the rise of geopolitics: “The best we can do is have factories in many parts of the world,” Musk said. “If things get difficult in one part of the world, we can still keep things going in the rest.”