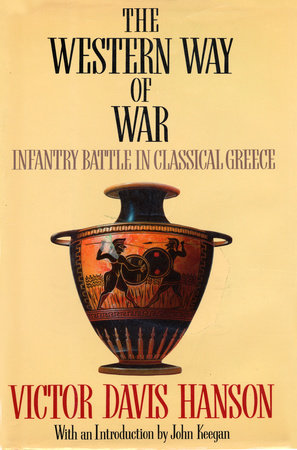

古典时代的希腊人不仅发明了西方政治的中心思想——国家权力应该由大多数公民来指导——而且还发明了西方战争的核心行为,即决定性的步兵战斗。 公元前五世纪的希腊人不再采取伏击、小规模冲突、机动或个人英雄之间的战斗。 在各个年龄段的武装人员之间设计了一场凶猛、短暂且具有破坏性的正面冲突。 在这项大胆、原创的研究中,维克多·戴维斯·汉森展示了这个残酷的企业如何致力于实现与共识政府相同的结果——明确、立即解决争端。

《西方战争方式》借鉴了一系列非凡的资源——希腊诗歌、戏剧、花瓶绘画以及历史记录——来描述战场上实际发生的事情。 这是第一个从步兵的角度来探索古典希腊战争的实际机制的研究——残酷的长矛刺击,穿着沉重的青铜盔甲进行战斗的困难,这使得他们很难看到、听到和移动,以及 害怕。 汉森还讨论了士兵的身体状况和年龄、武器装备、伤口和士气。

对古希腊人杀戮场上发生的事情的令人信服的描述最终表明,他们的武器和战斗风格是经过精心设计的,通过使战斗经历尽可能具有决定性和可怕性,最大限度地减少时间和生命损失。 汉森将这种新的战斗方式与宪政政府的兴起联系起来,提出了新的问题并对关于战争历史的旧假设提出了质疑。

西方战争方式中有哪些希腊人?

https://defenceindepth.co/2021/10/21/which-greeks-in-the-western-way-of-war/

凯文·布拉克福德博士,国防研究部。 伦敦国王学院

“西方战争方式”(TWOW) 是历史学家维克多·戴维斯·汉森 (Victor Davis Hanson) 定义的一个概念,他将古希腊人和他们决定性的步兵战斗形式视为独特的西方传统的源泉。 这是训练有素的公民士兵的理想,能够在决定性的战斗中击败敌人,在自由社会中明确区分战争与和平。 西方战争传统的核心理念是,双方同意的政府能够利用直接武力以明确、有力的方式战胜对手。 TWOW 的“震撼与敬畏”和杀伤力,依赖于更好的技术和决定性的压倒性力量,与伏击、小冲突或个人战斗形成鲜明对比,这些被认为是自由西方国家所不具备的特征。

如今,这种向西方发动战争的理想继续引发关于美国是否已经失去“杀戮艺术”,或者美国如何受到西方理想束缚的争论,甚至有一个 RUSI 播客专门致力于理解“西方”这个词。 战争方式”。 至关重要的是,人们越来越担心非西方大国的“龙与蛇”已经学会克服西方的优势和战争方式。 英国国防部甚至担心“对手已经研究了西方的战争方式”并学会了适应新的能力。 将这些对西方战争方式衰落的担忧结合起来,是担心西方的军事主导地位受到威胁,以及敌对大国在寻求直接对抗时不会遵守规则。

TWOW 及其可追溯到古希腊的西方例外论框架对于理解当代挑战来说是一个糟糕的指南。 当前战略文献的趋势常常陷入本质主义论点,这些论点侧重于文化差异来解释广泛的结果。 这在家庭手工业中尤为明显,家庭手工业的兴起将混合战争和“小绿人”解释为一种独特的俄罗斯现象,其基础是俄罗斯民族性格的缺陷和俄罗斯人之间的差异性文化。 创造这样的原始理由来解释战略行为会简化历史并夸大差异。 将理性的西方与集中压倒性的力量与依赖狡猾和欺骗的非理性的东方进行对比,会产生基于可疑假设的非历史论点。 西方以独特方式作战的观念也引发了令人不安的刻板印象和陈词滥调,并且容易受到对东方主义的批评,如下所述。

TWOW 建立在自由城邦的神话化观点之上,公民士兵捍卫自由国家,这种观点可以追溯到古代古典时代。 因此,它发展了一种关于西方战争的道德叙述和意识形态观点,而这种观点并没有得到古希腊战争历史的支持。 这种保卫自由城邦的公民士兵的理想主义忽视了希腊城邦及其东部波斯对手经常使用希腊雇佣军。 但这只是西方拥有独特战争方式这一概念背后的众多历史上有问题的信念之一。

西方寻求以压倒性的武力展示进行直接对抗的想法可能会让古希腊人自己感到惊讶,他们赞扬奥德修斯等传奇英雄,因为他狡猾、狡猾和操纵性的行为让对手感到困惑和惊讶。 认为西方不会采取这种形式的诡计的信念表明,只有东方大国才有能力利用间接武力和诡计来获得优势。 TWOW声称西方寻求直接决战,但却悄悄地忽视了单极时代已经看到西方技术在无人机和隐形轰炸机方面占据主导地位,这些技术明确用于突袭对手和欺骗对手。 因此,尚不清楚西方或东方的战争方式之间是否存在明显的文化差异。

东方主义者对东方战争的描绘可能集中于孙子高超的欺骗策略,或武士的光荣风格。 第二次世界大战中日本帝国的神风特攻队飞行员是东方战争方式的一个明显例子。 神风特攻队飞行员以牺牲自己的生命为代价,以冷静、有节制的自我牺牲精神瞄准薄弱环节,这被视为与西方战争方式背道而驰。 然而,西方军队在第一次世界大战战场上缓慢前进的过程表明,在面对更强大的防御形式时,牺牲、荒谬的勇敢行为以及生命损失之间存在着有趣的相似之处。

这些历史例子挑战了西方和东方战争方式作为不同和稳定类别的概念。

TWOW 方法建立在理想化的古典古代历史之上,作为独特的西方传统的源泉,但古代晚期的不那么迷人的时代和“黑暗时代”呈现出更为复杂的景象。 为了理解实力的衰落、新竞争对手的崛起和技术适应,也许我们不应该关注古希腊人,而应该关注讲希腊语的拜占庭人。

拜占庭帝国的历史表明,不同的文化和战争方式可以采用相似的战术和战略来面对相似的物质和行动限制。 拜占庭帝国和中国唐朝对游牧草原武士到来的反应就是一个例子。 拜占庭是以君士坦丁堡为中心的东罗马帝国,距离中国唐朝有3000多英里,但在公元6-7世纪左右,两国都面临着草原游牧民族的大规模入侵。

在古代晚期的这个时期,突厥骑兵的大规模入侵威胁着拜占庭和中国的定居社会。 尽管这两个帝国相距甚远,但游牧战士非常擅长利用骑马射箭、快速突袭、伏击和佯装飞行战术进行战争,这给防御带来了一系列类似的问题。 中国将军李靖和被称为战略的拜占庭战争手册针对游牧战争方式制定了共同的主题。 双方都试图利用谈判来攻击土耳其人的营地,并且都看到了在敌对领土上保卫辎重列车的重要性。

同样,拜占庭人和李靖主张以防御部队控制战场阵地,分兵进攻和前进。 然而最值得注意的是,中国人和拜占庭人都对队形的秩序和控制表示担忧,以免落入游牧民族假装逃跑的陷阱。 游牧草原武士的出现创造了一种新的战争形式,对中国和拜占庭的定居帝国提出了挑战。 为了应对草原游牧民族的战术,每个帝国都制定了类似的解决方案,重点是集中力量、保护后勤和控制纪律严明的队形。 这个简短的例子表明,由于物质和战略限制,而不是基于文化差异的解释,类似的过程可以发展。

今天,中国和俄罗斯修正主义的崛起反映了美国及其盟国已经失去了冷战后的主导地位。 然而,为了理解中国的崛起,战略辩论仍然把目光投向古希腊人和修昔底德。 这是修昔底德关于伯罗奔尼撒战争的起因是雅典实力的增强和斯巴达的恐惧的著名言论,被概括为“修昔底德陷阱”。 因此,古希腊历史被用来形容美中关系正走向战争。 但讲希腊语的拜占庭人面临着与萨珊波斯人的强大竞争。 拜占庭-萨珊王朝的帝国冲突并不是一个大国崛起和衰落导致大国战争的故事,而是一个更复杂的故事,讲述了一场长达400年的对抗,双方在美索不达米亚两岸建立了缓冲区。 。

这两个帝国之间的竞争形成了两个利益分割的体系,波斯国王将其称为地球的“两只眼睛”。 今天,将世界划分为两种相互竞争的国际秩序愿景是一种现实的可能性。 修昔底德陷阱给人一种不可避免的感觉,但美国和中国也有可能同样寻求创造利益范围。 古希腊历史和修昔底德可以成为战略辩论的有用指南,但认识到后来讲希腊语的拜占庭人提醒我们,我们应该避免基于对文化身份的有限解读而提出宏大的主张和本质主义的论点。

TWOW 是一个关于西方战争方式的神话框架,它通常始于古希腊人,并将“西方”的理想视为古典世界的产物。 罗马的衰落在很大程度上被西方视为一场灾难性事件,它开启了一段黑暗时代,东方帝国的延续,而讲希腊语的拜占庭人因此被悄悄遗忘。 拜占庭帝国并不完全符合“西方”的经典,其历史教训也被忽视。 但正如本文试图简要表明的那样,TWOW 建立在本质主义文化差异的简单化方法之上。 拜占庭战争的历史呈现出一幅更加复杂的图景,这动摇了西方独特的战争方式的想法。 TWOW 是一个傲慢且有历史缺陷的概念,需要被抛弃。

希腊重装步兵与“西方战争方式”

这篇短文是 2012 年春季为 CAMS 180:古代战争而写的,作为我对一个小组项目的贡献,该项目定义了维克多·戴维斯·汉森 (Victor Davis Hanson) 称为“西方战争方式”的模型,并分析了我们目前对希腊重装步兵的了解如何反驳或支持 这个假设。

西方战争方式:

它是什么?

“西方战争方式”是由维克多·戴维斯·汉森(Victor Davis Hanson)开发的流行模型,描述了现代欧洲(或西方)战争和战斗礼仪的起源。

汉森认为,西方战争方式是传统的意识形态,即战争应该在军队之间预先安排好的、决定性的短期军事冲突中进行,而不是使用欺骗性的战争战术。 游击战和撤退被认为是懦弱的行为,而只有与敌人直接对抗才能获得荣誉和荣耀。 此外,西方对战争成功或不成功的定义完全取决于其决定性,这意味着战争只能通过在结束时有明显的赢家和明显的输家来决定。

典型的“西方”军队进行决斗式的“人对人的战斗”,通常是由类似的武装人员以严格的队形进行战斗。 就像18世纪的英国军团一样,他们的声誉建立在战场英勇的基础上,冒着死亡的危险,按照战斗规则坚守阵地击败敌人,这就是西方标准中勇敢的定义。 偏离规则是为那些必须“作弊”才能获胜的低等懦夫和失败者保留的。

西方战争方式的起源:

汉森指出,这些决斗观念和对战争的态度是西方独有的,可以追溯到古典希腊重装步兵。 根据汉森的模型,重装步兵从事高度仪式化的痛苦战争系统,这在方阵中得到体现。 汉森坚持认为,重装步兵方阵的功能、布局和装备的演变是为了强调这种仪式化的意识形态,这种意识形态厌恶撤退,强调联合行动、凝聚力和前进。

支持西方战争方式的论点:

通过将方阵解释为极其紧密的阵型,并通过字面解释重装步兵奥提莫斯的“推”,汉森的方阵战争模型似乎解释了重装步兵装备的某些不寻常的方面,包括背板、枪托尖刺和盾牌的凹度1。

更重要的是,汉森的仪式化重装步兵战争模型可以解释方阵所缺乏的东西,即射弹的整体使用。 “这种对近距离面对面杀戮的故意依赖解释了希腊文学中另一个普遍蔑视的对象:那些从远处作战的人,轻装的散兵或轻盾兵,标枪投掷者,投石手,尤其是弓箭手 ”2 在《伊利亚特》和希腊人看来,射箭本身几乎被认为是“作弊”。 这是一种违反一对一有序战斗荣誉准则的战争策略。 任何胆怯的农民都可以在安全距离内用弓箭杀人,但这需要一个真正的男人来近距离和个人战斗。

根据汉森的说法,重装步兵战争的另一个决斗属性仍然是“西方战争方式”,那就是它习惯在预先确定的地点举行预先安排的战斗。 希罗底德在他的著作中讲述了马尔多尼奥斯(薛西斯的表弟)写给薛西斯的一封关于重装步兵战争程序的信,“这些希腊人习惯于以最毫无意义的方式在彼此之间发动战争......因为一旦他们宣布 互相争斗时,他们会寻找最公平、最平坦的地方,然后下去战斗。 结果,即使是胜利者也会带着巨大的损失离开; 我不必提及被征服者,因为他们已经被消灭了。” 3

此外,数百年后,波利比乌斯将当前的罗马战争与古希腊人的战争进行了对比,“古人选择不通过欺骗来征服敌人,他们认为除非在公开的战斗中粉碎对手的精神,否则任何成功都是辉煌或安全的。 因此,他们彼此同意不使用隐藏的导弹或远距离发射的导弹,他们认为只有肉搏战才是真正决定性的。 因此他们提前宣战、宣战,宣布部署的时间和地点。 但现在他们说只有可怜的将军才会在战争中公开做任何事情(13.3.2-6)”4

当然,这些段落暗示希腊人并不关心牵制或游击战术,而是更喜欢东方邻国所不具备的更快、更具决定性的战斗形式。

反对“西方战争方式”的论点

现代战争方法起源于古典重装步兵的观点可能既不完全正确,也不完全错误。 事实是,仍然没有证据表明远古时代有“纯粹的”重装步兵战争,这意味着我们仍然只能感染

从我们后来掌握的证据来看。 此外,波利比乌斯和希罗底德的著作也不能完全准确,因为一篇是为了娱乐,另一篇是几百年后写的,是对“美好时光”的怀念。

此外,汉森的西方战争方式模型将对决断性的渴望称为西方的,同时暗示东方或非欧洲的战争是直接相反的。 “正是西方渴望步兵之间发生一次壮观的碰撞,渴望在自由人之间的战场上用锋利的武器进行残酷的杀戮,这让我们来自非西方世界的对手困惑和恐惧了 2500 多年。” 5 然而,将非西方人描绘成只参与非决定性和欺骗性的游击战,这是一个本质上的缺陷。 近东军队并没有避免预先安排的决定性战斗,米吉多战役(约公元前 1479 年)、卡尔卡尔战役(公元前 853 年)和蒂尔图巴战役(约公元前 653 年)的记载就证明了这一点。 。 如果汉森相信这一点,“公元前七世纪初的希腊就首次表达了对一场可怕的武力冲突的渴望……这在欧洲历史上是第一次……在短短几个小时内找到决定性的胜利或彻底的失败, ”比古典重装步兵早近 800 年前,东方人就开始实行决定性的预先安排的战争。 6 认为重装步兵具有发起决定性的预先安排的战争的原始且独特的愿望的假设是完全不准确的。

此外,认为希腊人没有利用欺骗手段的观点本质上也是错误的。 从军事演习到反情报和秘密行动,希腊人毫不犹豫地对敌人使用欺骗手段。 似乎只有当欺骗被用来对付希腊人时,才会被认为是懦弱的行为。 例如,在温泉关战役中,希腊人在不同地点佯装撤退,结果却转身屠杀追击的波斯人;在萨拉米斯战役中,地米斯托克利欺骗薛西斯相信他们已经投降,以阻止自己的军队撤退。 公元前 396 年,“斯巴达海军上将法拉基达斯在前往迦太基封锁下的锡拉丘兹的途中,俘获了九到十艘迦太基三层战舰,将自己的人放进去,然后拖着自己的船只驶过迦太基人。” 7

在另一个例子中,“得知色雷斯人打算在夜间攻击他的营地,伊菲克拉特斯留下了许多火堆(给人留下营地仍然被占领的印象)并隐藏了他的部下,他们攻击并击败了进攻的色雷斯人。” 8 即使在《伊利亚特》中,特洛伊人也被希腊人通过欺骗击败。

因此,虽然预先安排的决战既不是西方军队的原创,也不是独一无二的,而且重装步兵当然也没有放弃使用欺骗手段,但很难说古希腊人在塑造我们现代西方关于战争如何进行的观念中发挥了什么作用。 应该发工资。 在过去 200 年间,人们对什么是标准战争或不被认为是光荣战争的态度已经发生了显着的变化,更不用说在过去 2,600 年里了。

1 Victor Davis Hanson,《西方战争方式》,(纽约:Alfred A. Knopf,1989 年),第 1 章。 6.

我对西方战争方式有疑问

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/2sb5wh/i_have_a_problem_with_the_western_way_of_war/?

我目前正在阅读维克多·戴维斯·汉森(Victor Davis Hanson)的《西方战争方式》一书,他一遍又一遍地声称,两支军队在开阔的战场上进行激战的想法起源于希腊古典时期。

我之前读过保罗·克里瓦切克(Paul Kriwaczek)写的《巴比伦:美索不达米亚和文明的诞生》,书中认为苏美尔人和其他美索不达米亚城邦如乌尔和乌鲁克会排列军队并互相冲锋,就像希腊人所做的那样。

我承认我只读了《TWWoW》的一章,但其中的主张一直困扰着我。 这是对汉森的公平解读,还是奖学金已经继续进行?

kasirzin u/kasirzin 2014 年 3 月 1 日 •9 岁。 前

战争方式和战略文化的整个子领域确实有点混乱,有相当多的热度和相对较少的启发。 尽管如此,VDH 的基本论点仍然保留了一定的分量(至少,对于仍然要出版的攻击它的书籍来说,有足够的分量),部分原因是它是民族中心主义的,而且在某种程度上让我们西方人自我感觉良好。 毕竟,如果欧洲(以及后来的美国)不是那么独特,他们怎么会在军事上取得如此出色的成绩呢? 不幸的是,许多关于文化和战争方式的讨论确实往往会陷入刻板印象。

我目前正在读一本书(大约读了一半),该书反对 VDH 的论文,名为《危险的荣耀:西方军事力量的崛起》,作者是约翰·弗朗斯。 在这里,他将战争方式简化为两种基本模式:步兵的近距离冲突,这种冲突不是源自西方,而是源自农业城市社会(包括希腊,也包括美索不达米亚人和中国人),以及基于流动性和机动性的战争风格。 草原人民的战争。 除了这种简化之外,他还确定了攻击对手的三种方式:战斗、针对敌人经济实力的破坏和围攻。 他认为,在历史的大部分时间里,这两种类型的战争大致处于平衡状态。 由于蒙古人和奥斯曼人的成功(标志着奥斯曼帝国在维也纳面前失败的结束日期),草原战争从大约 1200 年到 1683 年取得了优势。 他描述了草原战争如何主宰欧亚大陆和中东的大部分地区,因为这些地区的大部分地区都是草原人民可以进入的,并且拥有维持草原军队的联系和资源。 欧洲作为世界最大大陆附近的山地半岛,与这些事件隔绝,因为大型草原军队根本无法在那里维持生计,从而导致出现一种截然不同的战争方式。 中国还成功地保持了自己的风格,这在很大程度上要归功于它吸收入侵者的能力。

然而,即使在这种独特的欧洲风格中,战斗仍然相对较少。 围攻更加频繁,部分原因是城市和堡垒标志着对领土的控制,这是战争的巨大战利品之一。 城市和堡垒意味着土地,因此也意味着财富和声望。 在历史上的大部分时间里,经济实力的破坏是欧洲战争的常态。 这比战斗的胜利或围攻的胜利更容易实现。

我读到了 1683 年,当时正值欧洲开始统治其他国家的风口浪尖。 尽管法国表示,由葡萄牙开始并由其他国家继续进行的海上探险是欧洲人试图绕过奥斯曼帝国所体现的草原的绝对力量,直接到达中国和印度的一个例子。 他还指出,欧洲人并没有真正做好与当地人开战的准备,而且在许多地方,他们必须与强大的对手作战,因此他们很难取得进展。

VDH 的一些基本思想仍然很受欢迎,但学术界正在努力继续前进。

ThoughtRiot1776 •9 年。 前

他的论文的大部分内容不也是公民的军事角色以及希腊人如何进行仪式化的战争方式以限制损失和领土获取吗?

我读这本书已经有一段时间了,但我很确定他比声称希腊人是第一个使用盾墙的人更深入。

。。。。。。。

The Western Way of War,Infantry Battle in Classical Greece

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/74938/the-western-way-of-war-by-victor-davis-hanson/9780307831552

Author Victor Davis Hanson

The Greeks of the classical age invented not only the central idea of Western politics--that the power of state should be guided by a majority of its citizens--but also the central act of Western warfare, the decisive infantry battle. Instead of ambush, skirmish, maneuver, or combat between individual heroes, the Greeks of the fifth century b.c. devised a ferocious, brief, and destructive head-on clash between armed men of all ages. In this bold, original study, Victor Davis Hanson shows how this brutal enterprise was dedicated to the same outcome as consensual government--an unequivocal, instant resolution to dispute.

The Western Way of War draws from an extraordinary range of sources--Greek poetry, drama, and vase painting, as well as historical records--to describe what actually took place on the battlefield. It is the first study to explore the actual mechanics of classical Greek battle from the vantage point of the infantryman--the brutal spear-thrusting, the difficulty of fighting in heavy bronze armor which made it hard to see, hear and move, and the fear. Hanson also discusses the physical condition and age of the men, weaponry, wounds, and morale.

This compelling account of what happened on the killing fields of the ancient Greeks ultimately shows that their style of armament and battle was contrived to minimize time and life lost by making the battle experience as decisive and appalling as possible. Linking this new style of fighting to the rise of constitutional government, Hanson raises new issues and questions old assumptions about the history of war.

Which Greeks in the Western Way of War?

https://defenceindepth.co/2021/10/21/which-greeks-in-the-western-way-of-war/

Dr Kevin Blachford, Defence Studies Department. King’s College London

The “Western way of war” (TWOW) is a concept that was most notably defined by the historian Victor Davis Hanson who viewed the Ancient Greeks and their form of decisive infantry battle as the wellspring of a unique Western tradition. It is an ideal of well drilled citizen-soldiers able to defeat the enemy in a decisive battle, with a clear distinction between war and peace in a free society. Central to this tradition of Western warfare is the idea that consensual governments are able to make use of direct force to overcome an adversary in a clear emphatic manner. The “shock and awe” and lethality of TWOW, with its reliance on better technology and decisive overwhelming force stands in contrast to the ambushes, skirmishes, or individual combat that are viewed as uncharacteristic of liberal Western states.

Today, this ideal of waging Western war continues to inspire debates about whether the US has lost the ‘art of killing’, or how the US is constrained by its Western ideals, with even a RUSI podcast dedicated to understanding this term, ‘the Western way of war’. Crucially, there is also increased concern that the ‘dragons and the snakes’ of non-Western powers have learned to overcome the Western advantages and approach to warfare. The British Ministry of Defence even raises concerns that ‘adversaries have studied the Western way of war’ and have learned to adapt with new capabilities. Uniting these concerns of a Western way of war in decline is the fear that the West’s military dominance is under threat and that rival powers will not play by the rules in seeking direct confrontation.

TWOW and its framework of Western exceptionalism stretching back to Ancient Greece is a poor guide to understanding contemporary challenges. Current trends in strategic literature all too often fall into essentialist arguments which focus on cultural differences to explain broad outcomes. This is particularly apparent with the cottage industry which has sprung up to explain hybrid warfare and ‘little green men’ as a uniquely Russian phenomenon based on flaws in the Russian national character and a culture of otherness among Russians. Creating such primordialist reasons to explain strategic behaviour simplifies history and exaggerates difference. Contrasting a rational West with focused overwhelming power against an irrational East reliant on cunning and deception creates ahistorical arguments based on questionable assumptions. The notion that the West fights in a distinct manner also raises troubling stereotypes, cliches, and is open to critiques of orientalism, as the following explains.

TWOW builds upon a mythologised view of a free polis with citizen-soldiers defending the liberal state which dates back to the classical age of antiquity. It therefore develops a moral narrative and ideological view of Western war which is not supported by the history of Ancient Greek warfare. This idealism of citizen-soldiers defending a free polis overlooks that there were often Greek mercenaries used by both the Greek city states and by their eastern Persian adversaries. But this is just one of the many historically problematic beliefs which underlie the concept of the West having a distinct way of war.

The idea that the West seeks direct confrontation in an overwhelming show of force may surprise the Ancient Greeks themselves who celebrated legendary heroes, such as Odysseus, for his cunning, sly and manipulative acts which confounded and surprised opponents. The belief that the West refrains from such forms of guile suggests that only Eastern powers are capable of using indirect force and trickery to gain an advantage. TWOW’s claim that the West seeks direct decisive battle then quietly overlooks that the unipolar era has seen the dominance of Western technology with drones and stealth bombers which are explicitly used to surprise an opponent and deceive adversaries. It is far from clear therefore, that there are any distinct cultural differences between a Western or Eastern approach to war.

Orientalist portrayals of Eastern war may focus on Sun Tzu’s masterful strategies of deception, or the honorable style of the Samurai warriors. A clear example of the Eastern way of war could be seen in the kamikaze pilots of the Japanese empire in the Second World War. The calm, measured self-sacrifice of kamikaze pilots to target areas of weakness at the cost of their own lives is seen as antithetical to a Western way of war. Yet, the slow onward march of Western troops across the fields of the First World War suggests interesting parallels of sacrifice, nonsensical acts of bravery and the loss of life against much stronger forms of defence.

Such historical examples challenge the notion of a Western and Eastern way of war as distinct and stable categories. TWOW approach builds upon an idealised history of classical antiquity as the wellspring of a unique Western tradition, but the less glamorous era of late antiquity and the ‘dark ages’ presents a more complicated picture. To understand declining power, the rise of new rivals and technological adaptation perhaps we should look not to the Ancient Greeks, but the Greek speaking Byzantines.

The history of the Byzantine empire shows that both different cultures and approaches to war can convene on similar tactics and strategies to face similar material and operational constraints. One example of this can be seen with the responses of the Byzantine empire and China’s Tang dynasty to the arrival of nomadic steppe warriors. Byzantium was the east Roman empire centred on Constantinople, which existed over 3,000 miles away from the Tang dynasty in China and yet both powers around the 6-7th centuries A.D faced considerable incursions by steppe nomads.

The large incursions of Türk cavalry forces during this era of late antiquity threatened to overwhelm the sedentary societies of both Byzantium and China. Nomadic warriors who were highly proficient in warfare that utilised horseback archery, fast raids, ambushes and tactics of feigned flight created a similar set of problems for defence despite the considerable distance between these two empires. The Chinese general Li Jing and the Byzantine manual of war, known as the strategikon, developed common themes in response to the nomadic ways of war. Both sought to exploit negotiations in order to attack the camps of the Türks and both saw the importance of defending baggage trains in hostile territory.

Equally, the Byzantines and Li Jing advocated having defensive troops to control positions on the battlefield, with separate troops for assault and moving forward. Most notably however, the Chinese and Byzantines each expressed concern for the order and the control of formations in order not to fall into the trap of the nomad’s feigned flight. The appearance of the nomadic steppe warriors created a new form of warfare which challenged the sedentary empires of China and Byzantium. In response to the tactics of steppe nomads each empire developed similar solutions focused on concentrating mass, protecting logistics and controlling disciplined formations. What this brief example suggests is that similar processes can develop due to material and strategic constraints, rather than explanations based on cultural differences.

Today, the rise of China and Russian revisionism is a reflection that the US and its allies have lost their post-Cold War dominance. Yet, to understand the rise of China, strategic debates continue to look to Ancient Greeks and Thucydides. It is Thucydides’ famous statement on the causes of the Peloponnesian war arising from the growing power of Athens and the fear this causes in Sparta, which has been summarized as the “Thucydides trap”. Ancient Greek history is therefore used to portray the US-China relationship as heading on a railroad to war. But the Greek speaking Byzantines faced their own great power rivalry with the Sasanid Persians. The Byzantine-Sasanid clash of empires was not a story of a rising and declining power leading to a great power war, but a more complicated story of a 400-year-old rivalry that saw the two sides develop a buffer zone between them across Mesopotamia.

The competition between these two empires created a system of two divided spheres of interests, which the Persian King referred to as the “two eyes” of the Earth. The division of the world into two competing visions of international order is a realistic possibility for today. The Thucydides trap presents an air of inevitability, but it is just as possible that the US and China will equally seek to create spheres of interest. Ancient Greek history and Thucydides can be useful guides to strategic debates but recognising the later Greek speaking Byzantines offers a reminder that we should avoid making grand claims and essentialist arguments based on a limited reading of cultural identity.

TWOW is a framework for myth-making about Western approaches to war which often begins with the Ancient Greeks and valorises an ideal of “the West” as a product of the classical world. The fall of Rome is largely viewed by the West as a cataclysmic event which ushered in a period of dark ages and the continuation of the Eastern empire as the Greek speaking Byzantines is therefore quietly forgotten. The empire of Byzantium does not fit neatly into the canon of “the West” and its historical lessons are neglected. But as this article has tried to briefly show, TWOW builds upon a simplistic approach of essentialist cultural differences. The history of Byzantine warfare presents a more complicated picture which unsettles the idea of a distinct Western approach to war. TWOW is a hubristic and historically flawed concept which needs to be left behind.

Greek Hoplites and the”Western Way of War”

https://sites.psu.edu/sarahreeseeportfolioeng202a/greek-hoplites-and-thewestern-way-of-war-2/

This short piece was written ,Spring 2012 for CAMS 180: Ancient Warfare, as my contribution to a group project defining a model by Victor Davis Hanson called the “Western Way of War” and analyzing how our current knowledge of the Greek Hoplites refutes or supports this hypothesis.

Western Way of War: What is it?

The “Western Way of War” is a popular model developed by Victor Davis Hanson describing the origins of modern European (or Western) warfare and battle etiquette.

According to Hanson, the Western Way of War is the traditional ideology that wars should be fought in short pre-arranged and decisive military clashes between armies without the use of deceptive war tactics. Guerrilla warfare and retreat are deemed cowardly, while honor and glory can be achieved only through direct confrontation with the enemy. Also, the Western definition of a successful or unsuccessful war rests entirely on its decisiveness, meaning a war can only be decided by having a distinct winner and a clear loser at its conclusion.

A prototypical “Western” army engages in duellistic “man-to-man battles”, usually with similarly armed individuals fighting it out in strict formation. Like the 18’th century British Regiments, whose reputations were built on battlefield gallantry, risking death and holding your ground to defeat your enemy according to the rules of combat is the definition of bravery by Western standards. Deviation from the rules is reserved for the inferior cowards and losers who have to “cheat” to win.

Origins of the Western Way of War:

Hanson states that these duellistic notions and attitudes towards warfare are unique to the west and date all the way back to the Classical Greek Hoplites. According to Hanson’s model, Hoplites engaged in a highly ritualized agonal system of warfare, which manifested itself in the phalanx. Hanson insists that the function, arrangement, and equipment of the Hoplite phalanx evolved to emphasize this ritualistic ideology which abhorred retreat and stressed joint action, cohesion and forward movement.

Arguments For the Western Way of War:

By interpreting phalanxes as extremely tight formations, and by interpreting the Hoplite Othismos “push” literally, Hanson’s Model of phalanx warfare seemingly explains certain unusual aspects of Hoplite equipment including the back-plates, butt spikes, and the concavity of the shields1.

More importantly, Hanson’s Model of ritualized Hoplite warfare may explain what is lacking from the phalanx, namely the overall use of projectiles. “This deliberate dependence on face-to-face killing at close range explains another universal object of disdain in Greek literature: those who fight from afar, the lightly equipped skirmisher or peltast, the javelin thrower, the slinger, and above all, the archer.”2 In the Iliad and to the Greeks, archery in itself is almost considered to be “cheating.” It is a war tactic which violates the honor-codes of man-to-man ordered combat. Any cowardly peasant can kill from a safe distance with a bow, but it requires a real man to fight up-close and personal.

According to Hanson, another duellistic attribute of Hoplite warfare which remained a “the Western Way of War” was its custom to hold pre-arranged battles in pre-determined locations. In his writings, Heroditus tells of a letter written to Xerxes by Mardonios (Xerxes’ cousin) on the procedures of Hoplite warfare, “these Greeks are accustomed to wage their wars among each other in the most senseless way…For as soon as they declare war on each other, they seek out the fairest and most level ground, and then go down there to do battle on it. Consequently, even the winners leave with extreme losses; I need not mention the conquered, since they are annihilated.” 3

Also, hundreds of years later Polybius contrasted the current Roman warfare with that of the ancient Greeks, “The ancients chose not to conquer their enemies by deception, regarding no success as brilliant or secure unless they crushed their adversaries’ spirit in open battle. For this reason they agreed with each other not to use hidden missiles or those discharged from a distance against each other, and they considered only a hand-to-hand, pitched battle to be truly decisive. Therefore they declared wars and battles in advance, announcing when and where they were going to deploy. But now they say only a poor general does anything openly in war (13.3.2-6)” 4

Certainly these passages imply that the Greeks did not bother with diversionary or guerrilla tactics, and preferred a quicker more decisive form of battle not shared by their Eastern neighbors.

Arguments Against “The Western Way of War”

The idea that modern methods for waging war originated with the Classical Hoplites is probably neither completely true, nor completely false. The fact remains that there is still no evidence for “pure” Hoplite Warfare in the Archaic Era, meaning that we can still only infer from the later evidence we do have. Also, the writings of Polybius and Heroditus cannot be counted upon for complete accuracy, as one is for entertainment and the other was written hundreds of years later as a nostalgic longing for “the good old days”.

Also, Hanson’s Model of the Western Way of War, in calling the desire for decisiveness Western, simultaneously implies that Eastern or non-European warfare is the direct opposite. “It is this Western desire for a single, magnificent collision of infantry, for brutal killing with edged weapons on a battlefield between free men, that has baffled and terrified our adversaries from the non-Western world for more than 2,500 years.” 5 However, there is an essential flaw in portraying non-Westerners as engaging only in non-decisive and deceptive guerilla warfare. Near Eastern armies did not avoid pre-arranged decisive battles, as evidenced by accounts of the Battle of Megiddo (ca. 1479 B.C.), the Battle of Qarqar (853 B.C.), and the Battle of Til-Tuba (ca. 653 B.C.). If Hanson believes that this, “desire for an awesome clash of arms was first expressed in Greece at the beginning of the seventh century B.C…for the first time in European history… to find in a few short hours a decisive victory or utter defeat,” than decisive pre-arranged warfare was being practiced by Easterners almost 800 years prior to the Classical Hoplites. 6 The assumption that the Hoplites were original and unique in their desire to wage decisive pre-arranged warfare is totally inaccurate.

Furthermore, the idea that the Greeks did not utilize deception is also inherently false. From military maneuvers, to counter-intelligence and covert operations, the Greeks did not hesitate to use deception against their enemies. It seems the only time deception is considered cowardly, is when it is used against the Greeks. For example, at the Battle of Thermopylae the Greeks feigned retreats at various points, only to turn and slaughter the pursuing Persians, and at the Battle of Salamis Themistocles tricked Xerxes into believing they had surrendered, in order to block his own troops from retreating. In 396 B.C., “On his way to Syracuse, which was under Carthaginian blockade, the Spartan admiral Pharakidas captured nine or ten Carthaginian triremes, put his own men into them, and sailed past the Carthaginians, towing his own ships behind.” 7

In yet another instance, “Learning that the Thracians intended to attack his camp at night, Iphikrates left numerous fires (to give the impression the camp was still occupied) and hid his men, who attacked and defeated the attacking Thracians.” 8 Even in the Iliad, the Trojans are defeated by the Greeks through deception.

So, while pre-arranged decisive battles are neither original, nor unique to Western armies, and while the Hoplites certainly did not abstain from using deception, it is hard to tell what role the ancient Greeks had in shaping our modern Western ideas about how warfare should be waged. The attitudes revolving around what is or is not considered to be standard or honorable warfare has evolved significantly within the last 200 years, let alone the last 2,600 years.

1 Victor Davis Hanson, The Western Way of War, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989), chap. 6.

I have a problem with The Western Way of War

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/2sb5wh/i_have_a_problem_with_the_western_way_of_war/?

I'm currently reading Victor Davis Hanson's book The Western Way of War and over and over again he claims that the idea of two armies clashing together in a pitched battle on an open field originated in Greek classical antiquity.

I was reading Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization by Paul Kriwaczek before and in that book it is argued that the Sumerians and other Mesopotamian city states like Ur and Uruk would line their armies up and charge each other, just like the Greeks did.

I admit I have only got about a chapter into TWWoW but the claims made in it have been bothering me. Is this a fair reading of Hanson, or has the scholarship moved on?

The whole subfield of ways of war and strategic culture is a bit of a mess, really, with a rather lot of heat and relatively little illumination. That said, VDH's basic thesis still retains some weight (at least, sufficient weight for books still to be published attacking it), in part because it is ethnocentric, and moreover in a way that makes us in the west feel good about ourselves. After all, if Europe (and later the USA) weren't so unique, how did they end up doing so well for themselves militarily? A lot of discussion of culture and ways of war does tend to fall back upon stereotype, unfortunately.