一: 简.奥斯汀的草莓

父母刚来加拿大定居时,我们姐妹带着二老去郊外的自由采摘农场(U-Pick)摘草莓。摘草莓是个辛苦活,在大太阳底下晒着,不停地弯腰寻找,采摘。一个小时后,从未干过农活的我和妹妹就累得受不了啦,赶紧在地头找了个树荫坐下来乘凉。二老虽然是城里人,但年轻时下乡干过不少农活,吃苦精神明显胜过子女。我们休息的时候,他们俩又兴致勃勃地摘了一小时的草莓,装满了随身的竹篮。

自那以后,我宁可选择直着腰摘覆盆子、樱桃和蓝莓,也不愿再频繁弯腰碰草莓啦。

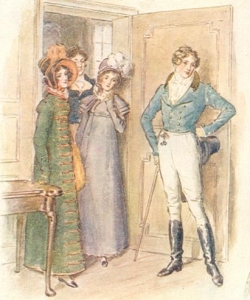

我记得简.奥斯汀(Jane Austen,1775年-1817年)在她的首版于1815年的经典小说《爱玛》(Emma) 里写有摘草莓的情景,通过埃尔顿太太的那张喋喋不休的利嘴,将采草莓的过程描述如下:

“英国最好的水果——人人都喜爱——总是棒极了。这是最好的草莓圃,最好的品种。自己采才有意思——只有这样吃起来才有滋味。上午无疑是最好的时间——决不会感到累——哪个品种都挺好——阔少爷比别的不知要好多少——真是无与伦比——别的简直不能吃——阔少爷草莓很少见——大家都喜欢辣椒莓——白木莓味道最好——伦敦的草莓价格——布里斯托尔产得多——枫园——培育——草莓圃什么时候翻整——园丁的想法不一致——没有统一规则——园丁决不会放弃自己的做法——鲜美的水果——只是太腻了,不宜多吃——不如樱桃——红醋栗比较清爽——采草莓的唯一缺点是要弯腰——太阳晃眼——累死了——再也受不了啦——得去树荫里坐坐。”

“The best fruit in England — every body’s favourite — always wholesome. These the finest beds and finest sorts. — Delightful to gather for one’s self — the only way of really enjoying them. Morning decidedly the best time — never tired — every sort good — hautboy infinitely superior — no comparison — the others hardly eatable — hautboys very scarce — Chili preferred — white wood finest flavour of all — price of strawberries in London — abundance about Bristol — Maple Grove — cultivation — beds when to be renewed — gardeners thinking exactly different — no general rule — gardeners never to be put out of their way — delicious fruit — only too rich to be eaten much of — inferior to cherries — currants more refreshing — only objection to gathering strawberries the stooping — glaring sun — tired to death — could bear it no longer — must go and sit in the shade.”

这是一段从自以为是、无所不知的热情到夕阳西下时的精疲力竭的滑稽荒唐的过程。不同生活阅历和教育背景的人读到这里,理解也是不同的。自从腰酸背痛地采过一次草莓后,我这位长在城里的大小姐的反映和埃尔顿太太是一样的:要弯腰——太阳晃眼——累死了——再也受不了啦——得去树荫里坐坐。

《爱玛》是奥斯汀生前的最后一部作品,虽然在中国读者中的反响不如《傲慢与偏见》及《理智与情感》,写作技巧却是最成熟的。

从第一部被发表的小说《理智与情感》起,简.奥斯汀创造了一种独特的被二十世纪初的文学评论家称为“自由简洁风格”(free indirect style , 源于法语style indirect libre)的写作手法,即以第三人称的话语与意念将读者带入小说情节中。创作《爱玛》时,她的写作技巧已到了登峰造极的地步。在奥斯汀之前,小说家要么以第一人称叙述故事,将读者限制在主人公的思想当中,要么以第三人称说故事,读者充当“上帝”的角色,冷眼旁观着故事中所有人物的一颦一笑。而奥斯汀则另辟蹊径,让读者走入第三人称爱玛的内心世界,随着她的主观意识去理解周围所发生的一切。

简.奥斯汀还在情节中大量地运用了破折号、感叹号以及断句,大大加强了故事的戏剧性。比如,二十岁的爱玛喜欢安排别人的生活,竭力为地位低下的女友海莉雅特(Harriet)寻找社会地位较高的配偶,结果却与她的愿望相反。一开始,她想方设法撮合海莉雅特与青年绅士埃尔顿,叫她拒绝了佃户罗伯特·马丁的求婚,然而势利的埃尔顿只对美貌富有的爱玛感兴趣。第一卷第十六章,发觉了真相后的爱玛无比沮丧。书中是这样描述的:

“发卷已经夹上,女佣已经打发走了,爱玛坐下来思索,感觉很凄惨。— 这的确是件可悲的事情!— 她所期望的每一件事都被搞砸了!— 所有的一切都朝着不受欢迎的方向发展!— 这对海莉雅特是如此沉重的打击!— 这是最糟糕的事。这件事的每一个方面都带来某种形式的痛苦和屈辱。但是与带给海莉雅特的危害相比,全都无足轻重。她情愿承受比实际情形更多的误解-更多的谬误-更多的由于错判而带来的耻辱,只要将她的错误导致的结果局限在她自己身上就行。

‘假如我没有劝说海莉雅特喜欢那个男人,我就可以承受这一切。即使他对我有两倍的假想 – 可怜的海莉雅特!’

她怎么会被如此蒙蔽呢!— 他口口声声说他从未认真考虑过海莉雅特 —从来没有!她尽量回顾过去发生的事情,但一切都是那么让人迷惑不解。她认为,一旦她有了想法,便会让一切事情都付诸实践。然而他的行为举止肯定不明确,摇摆不定,让人怀疑,不然她就不可能被误导。

那幅画!— 他对那幅画多么狂热啊! — 还有那个字谜!- 还有一百种其他场合 — 它们似乎都多么清楚地指向海莉雅特。可以肯定的是,那个字谜,写着“才思敏捷” — 后来又有“柔和的眼睛” – 事实上对两个姑娘都不合适。不过是个没有品味并不真实的含糊说法。谁能看穿这笨头笨脑的胡说八道呢?”

(The hair was curled, and the maid sent away, and Emma sat down to think and be miserable.—It was a wretched business indeed!—Such an overthrow of every thing she had been wishing for!—Such a development of every thing most unwelcome!—Such a blow for Harriet!—that was the worst of all. Every part of it brought pain and humiliation, of some sort or other; but, compared with the evil to Harriet, all was light; and she would gladly have submitted to feel yet more mistaken—more in error—more disgraced by mis-judgment, than she actually was, could the effects of her blunders have been confined to herself.

"If I had not persuaded Harriet into liking the man, I could have borne any thing. He might have doubled his presumption to me--but poor Harriet!"

How she could have been so deceived!--He protested that he had never thought seriously of Harriet--never! She looked back as well as she could; but it was all confusion. She had taken up the idea, she supposed, and made every thing bend to it. His manners, however, must have been unmarked, wavering, dubious, or she could not have been so misled.

The picture!--How eager he had been about the picture!--and the charade!--and an hundred other circumstances;--how clearly they had seemed to point at Harriet. To be sure, the charade, with its "ready wit"--but then the "soft eyes"--in fact it suited neither; it was a jumble without taste or truth. Who could have seen through such thick-headed nonsense?)

奥斯汀独创了大量运用感叹号和破折号的叙事手法,精彩地体现了一种戏剧化的思考过程。虽然她以第三人称的视角在叙述故事,但读者可以清清楚楚地了解女主人公的想法,探索她的内心感受并判断她的性格。

再举一个经典的例子:爱玛潜意识里爱着奈特利先生,却一直在自我欺骗,试图将自己游离于感情世界之外。第二卷第八章,韦斯顿太太向爱玛暗示:奈特利先生倾慕贝茨小姐的外甥女简·费尔法克斯,“她(爱玛)反对奈特利先生结婚,这一想法丝毫没有改变。她觉得那样做有百弊而无一利。那会使约翰·奈特利先生大为失望,伊莎贝拉也会大为失望。那几个孩子可真要倒霉了——给他们带来苦不堪言的变化,造成非同小可的损失 — 她父亲的日常安适要大打折扣——而她自己,一想到费尔法克斯要做当维尔寺的女主人,心里就受不了。一个他们大家都要谦让的奈特利太太!不 — 奈特利先生说什么也不能结婚。小亨利一定得做当维尔的继承人。”(Her objections to Mr. Knightley's marrying did not in the least subside. She could see nothing but evil in it. It would be a great disappointment to Mr. John Knightley; consequently to Isabella. A real injury to the children--a most mortifying change, and material loss to them all;--a very great deduction from her father's daily comfort--and, as to herself, she could not at all endure the idea of Jane Fairfax at Donwell Abbey. A Mrs. Knightley for them all to give way to!--No--Mr. Knightley must never marry. Little Henry must remain the heir of Donwell.)

接下来,第三卷第十一章,海莉雅特向爱玛倾吐了自己的爱幕对象是奈特利,“爱玛蓦地收回了目光,坐在那里静思,她以固定的姿势静静地坐了几分钟。这几分钟就足以让她看清了自己的内心。像她这样的头脑,一旦起了猜疑,就很快猜疑下去。她触到了- 她承认了- 她接受了整个事实。为什么海莉雅特爱上奈特利先生会比爱上弗兰克.邱吉尔糟糕得多呢?为什么海莉雅特有了一点希望,认为奈特利先生也有意于她,那就愈发可怕了呢?她脑子里像箭似的闪过一个念头:奈特利先生不能跟别人结婚,只能跟她爱玛!”

(Emma's eyes were instantly withdrawn; and she sat silently meditating, in a fixed attitude, for a few minutes. A few minutes were sufficient for making her acquainted with her own heart. A mind like hers, once opening to suspicion, made rapid progress. She touched-- she admitted--she acknowledged the whole truth. Why was it so much worse that Harriet should be in love with Mr. Knightley, than with Frank Churchill? Why was the evil so dreadfully increased by Harriet's having some hope of a return? It darted through her, with the speed of an arrow, that Mr. Knightley must marry no one but herself!)

以上这两段文字表明:爱玛的一系列主观臆想在现实中一一挫败,她终于从幼稚走向成熟,认清了自己的情感。

经过一番周折,奈特利和爱玛终于互吐衷情,罗伯特·马丁在奈特利的帮助下,最后也得到了海莉雅特的爱情。

简.奥斯汀无意将爱玛打造成一个完美的人设,把她的势利、自负、自以为是等缺点刻画得淋漓尽致,却获得了广大读者的喜爱,大家都喜欢自省后成熟起来的她最终获得幸福的结局。