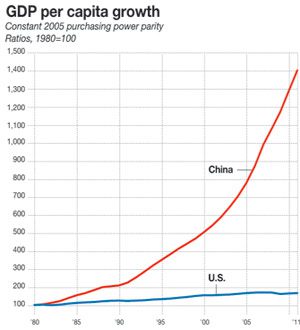

During the three decades following Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 reforms, China achieved the fastest sustained rate of economic growth in human history, with the resulting 40-fold rise in the size of China’s economy leaving it poised to surpass America’s as the largest in the world. A billion ordinary Han Chinese have lifted themselves economically from oxen and bicycles to the verge of automobiles within a single generation.

China’s academic performance has been just as stunning. The 2009 Program for International Student Assessment(PISA) tests placed gigantic Shanghai—a megalopolis of 15 million—at the absolute top of world student achievement. PISA results from the rest of the country have been nearly as impressive, with the average scores of hundreds of millions of provincial Chinese—mostly from rural families with annual incomes below $2,000—matching or exceeding those of Europe’s most advanced and successful countries, such as Germany, France, and Switzerland, and ranking well above America’s results.

These successes follow closely on the heels of a previous generation of similar economic and technological gains for several much smaller Chinese-ancestry countries in that same part of the world, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, and the great academic and socioeconomic success of small Chinese-descended minority populations in predominantly white nations, including America, Canada, and Australia. The children of the Yellow Emperor seem destined to play an enormous role in Mankind’s future.

These successes follow closely on the heels of a previous generation of similar economic and technological gains for several much smaller Chinese-ancestry countries in that same part of the world, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, and the great academic and socioeconomic success of small Chinese-descended minority populations in predominantly white nations, including America, Canada, and Australia. The children of the Yellow Emperor seem destined to play an enormous role in Mankind’s future.

Although these developments might have shocked Westerners of the mid-20th Century—when China was best known for its terrible poverty and Maoist revolutionary fanaticism—they would have seemed far less unexpected to our leading thinkers of 100 years ago, many of whom prophesied that the Middle Kingdom would eventually regain its ranking among the foremost nations of the world. This was certainly the expectation of E.A. Ross, one of America’s greatest early sociologists, whose book The Changing Chinese looked past the destitution, misery, and corruption of the China of his day to a future modernized China perhaps on a technological par with America and the leading European nations. Ross’s views were widely echoed by public intellectuals such as Lothrop Stoddard, who foresaw China’s probable awakening from centuries of inward-looking slumber as a looming challenge to the worldwide hegemony long enjoyed by the various European-descended nations.

The likely roots of such widespread Chinese success have received little detailed exploration in today’s major Western media, which tends to shy away from considering the particular characteristics of ethnic groups or nationalities, as opposed to their institutional systems and forms of government. Yet although the latter obviously play a crucial role—Maoist China was far less economically successful than Dengist China—it is useful to note that the examples of Chinese success cited above range across a wide diversity of socioeconomic and political systems.

For decades, Hong Kong enjoyed one of the most free-market, nearly anarcho-libertarian economic regimes; during that same period, Singapore was governed by the tight hand of Lee Kuan Yew and his socialistic People’s Action Party, which built a one-party state with a large degree of government guidance and control. Yet both these populations were overwhelmingly Chinese, and both experienced almost equally rapid economic development, moving in 50 years from total postwar destitution and teeming refugee slums to ranking among the wealthiest places on earth. And Taiwan, whose much larger Chinese-ancestry population pursued an intermediate development model, enjoyed similar economic success.

Despite a long legacy of racial discrimination and mistreatment, small Chinese communities in America also prospered and advanced, even as their numbers grew rapidly following passage of the 1965 Immigration Act. In recent years a remarkable fraction of America’s top students—whether judged by the objective winners’ circle of the Mathematics Olympiad and Intel Science competition or by the somewhat more subjective rates of admission to Ivy League colleges—have been of Chinese ancestry. The results are particularly striking when cast in quantitative terms: although just 1 percent of American high-school graduates each year have ethnic Chinese origins, surname analysis indicates that they currently include nearly 15 percent of the highest-achieving students, a performance ratio more than four times better than that of American Jews, the top-scoring white ancestry group.

Chinese people seem to be doing extremely well all over the world, across a wide range of economic and cultural landscapes.

Almost none of these global developments were predicted by America’s leading intellectuals of the 1960s or 1970s, and many of their successors have had just as much difficulty recognizing the dramatic sweep of events through which they are living. A perfect example of this strange myopia may be found in the writings of leading development economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, whose brief discussions of China’s rapid rise to world economic dominance seem to portray the phenomenon as a temporary illusion almost certainly soon to collapse because the institutional approach followed differs from the ultra-free-market neoliberalism that they recommend. The large role that the government plays in guiding Chinese economic decisions dooms it to failure, despite all evidence to the contrary, while America’s heavily financialized economy must be successful, regardless of our high unemployment and low growth. According to Acemoglu and Robinson, nearly all international success or failure is determined by governmental institutions, and since China possesses the wrong ones, failure is certain, though there seems no sign of it.

Perhaps such academics will be proven correct, and China’s economic miracle will collapse into the debacle they predict. But if this does not occur, and the international trend lines of the past 35 years continue for another five or ten, we should consider turning for explanations to those long-forgotten thinkers who actually foretold these world developments that we are now experiencing, individuals such as Ross and Stoddard. The widespread devastation produced by the Japanese invasion, World War II, and the Chinese Civil War, followed by the economic calamity of Maoism, did delay the predicted rise of China by a generation or two, but except for such unforeseen events, their analysis of Chinese potential seems remarkably prescient. For example, Stoddard approvingly quotes the late Victorian predictions of Professor Charles E. Pearson:

Does any one doubt that the day is at hand when China will have cheap fuel from her coal-mines, cheap transport by railways and steamers, and will have founded technical schools to develop her industries? Whenever that day comes, she may wrest the control of the world’s markets, especially throughout Asia, from England and Germany.

Western intellectual life a century ago was quite different from that of today, with contrary doctrines and taboos, and the spirit of that age certainly held sway over its leading figures. Racialism—the notion that different peoples tend to have different innate traits, as largely fashioned by their particular histories—was dominant then, so much so that the notion was almost universally held and applied, sometimes in rather crude fashion, to both European and non-European populations.

With regard to the Chinese, the widespread view was that many of their prominent characteristics had been shaped by thousands of years of history in a generally stable and organized society possessing central political administration, a situation almost unique among the peoples of the world. In effect, despite temporary periods of political fragmentation, East Asia’s own Roman Empire had never fallen, and a thousand-year interregnum of barbarism, economic collapse, and technological backwardness had been avoided.

On the less fortunate side, the enormous population growth of recent centuries had gradually caught up with and overtaken China’s exceptionally efficient agricultural system, reducing the lives of most Chinese to the brink of Malthusian starvation; and these pressures and constraints were believed to be reflected in the Chinese people. For example, Stoddard wrote:

Winnowed by ages of grim elimination in a land populated to the uttermost limits of subsistence, the Chinese race is selected as no other for survival under the fiercest conditions of economic stress. At home the average Chinese lives his whole life literally within a hand’s breadth of starvation. Accordingly, when removed to the easier environment of other lands, the Chinaman brings with him a working capacity which simply appalls his competitors.

Stoddard backed these riveting phrases with a wide selection of detailed and descriptive quotations from prominent observers, both Western and Chinese. Although Ross was more cautiously empirical in his observations and less literary in his style, his analysis was quite similar, with his book on the Chinese containing over 40 pages describing the grim and gripping details of daily survival, provided under the evocative chapter-heading “The Struggle for Existence in China.”

During the second half of the 20th century, ideological considerations largely eliminated from American public discourse the notion that many centuries of particular circumstances might leave an indelible imprint upon a people. But with the turn of the new millennium, such analyses have once again begun appearing in respectable intellectual quarters.

The most notable example of this would surely be A Farewell to Alms, Gregory Clark’s fascinating 2007 analysis of the deep origins of Britain’s industrial revolution, which was widely reviewed and praised throughout elite circles, with New York Times economics columnist Tyler Cowen hailing it as possibly “the next blockbuster in economics” and Berkeley economist Brad DeLong characterizing it as “brilliant.”

Although Clark’s work focused on many different factors, the one that attracted the greatest attention was his demographic analysis of British history based upon a close examination of individual testaments. Clark discovered evidence that for centuries the wealthier British had left significantly more surviving children than their poorer compatriots, thus leading their descendants to constitute an ever larger share of each generation. Presumably, this was because they could afford to marry at a younger age, and their superior nutritional and living arrangements reduced mortality rates for themselves and their families. Indeed, the near-Malthusian poverty of much ordinary English life during this era meant that the impoverished lower classes often failed even to reproduce themselves over time, gradually being replaced by the downwardly mobile children of their financial betters. Since personal economic achievement was probably in part due to traits such as diligence, prudence, and productivity, Clark argued that these characteristics steadily became more widespread in the British population, laying the human basis for later national economic success.

Leaving aside whether or not the historical evidence actually supports Clark’s hypothesis—economist Robert C. Allen has published a strong and fairly persuasive refutation—the theoretical framework he advances seems a perfectly plausible one. Although the stylistic aspects and quantitative approaches certainly differ, much of Clark’s analysis for England seems to have clear parallels in how Stoddard, Ross, and others of their era characterized China. So perhaps it would be useful to explore whether a Clarkian analysis might be applicable to the people of the Middle Kingdom.

Interestingly enough, Clark himself devotes a few pages to considering this question and concludes that in contrast to the British case, wealthier Chinese were no more fecund than the poorer, eliminating the possibility of any similar generational trend. But Clark is not a China specialist, and his brief analysis relies on the birth records of the descendants of the ruling imperial dynasty, a group totally unrepresentative of the broader population. In fact, a more careful examination of the Chinese source material reveals persuasive evidence for a substantial skew in family size, directly related to economic success, with the pattern being perhaps even stronger and more universally apparent than was the case for Britain or any other country.

Moreover, certain unique aspects of traditional Chinese society may have maintained and amplified this long-term effect, in a manner unlike that found in most other societies in Europe or elsewhere. China indeed may constitute the largest and longest-lasting instance of an extreme “Social Darwinist” society anywhere in human history, perhaps with important implications for the shaping of the modern Chinese people.

Chinese society is notable for its stability and longevity. From the gradual establishment of the bureaucratic imperial state based on mandarinate rule during the Sui (589–618) and T’ang (618–907) dynasties down to the Communist Revolution of 1948, a single set of social and economic relations appears to have maintained its grip on the country, evolving only slightly while dynastic successions and military conquests periodically transformed the governmental superstructure.

A central feature of this system was the replacement of the local rule of aristocratic elements by a class of official meritocrats, empowered by the central government and selected by competitive examination. In essence, China eliminated the role of hereditary feudal lords and the social structure they represented over 1,000 years before European countries did the same, substituting a system of legal equality for virtually the entire population beneath the reigning emperor and his family.

The social importance of competitive examinations was enormous, playing the same role in determining membership in the ruling elite that the aristocratic bloodlines of Europe’s nobility did until modern times, and this system embedded itself just as deeply in the popular culture. The great noble houses of France or Germany might trace their lineages back to ancestors elevated under Charlemagne or Barbarossa, with their heirs afterward rising and falling in standing and estates, while in China the proud family traditions would boast generations of top-scoring test-takers, along with the important government positions that they had received as a result. Whereas in Europe there existed fanciful stories of a heroic commoner youth doing some great deed for the king and consequently being elevated to a knighthood or higher, such tales were confined to fiction down to the French Revolution. But in China, even the greatest lineages of academic performers almost invariably had roots in the ordinary peasantry.

Not only was China the first national state to utilize competitive written examinations for selection purposes, but it is quite possible that almost all other instances everywhere in the world ultimately derive from the Chinese example. It has long been established that the Chinese system served as the model for the meritocratic civil services that transformed the efficiency of Britain and other European states during the 18th and 19th centuries. But persuasive historical arguments have also been advanced that the same is even true for university entrance tests and honors examinations, with Cambridge’s famed Math Tripos being the earliest example. Modern written tests may actually be as Chinese as chopsticks.

With Chinese civilization having spent most of the past 1,500 years allocating its positions of national power and influence by examination, there has sometimes been speculation that test-taking ability has become embedded in the Chinese people at the biological as well as cultural level. Yet although there might be an element of truth to this, it hardly seems likely to be significant. During the eras in question, China’s total population numbered far into the tens of millions, growing in unsteady fashion from perhaps 60 million before AD 900 to well over 400 million by 1850. But the number of Chinese passing the highest imperial exam and attaining the exalted rank of chin-shih during most of the past six centuries was often less than 100 per year, down from a high of over 200 under the Sung dynasty (960-1279), and even if we include the lesser rank of chu-jen, the national total of such degree-holders was probably just in the low tens of thousands,

a tiny fraction of 1 percent of the overall population—totally dwarfed by the numbers of Chinese making their living as artisans or merchants, let alone the overwhelming mass of the rural peasantry. The cultural impact of rule by a test-selected elite was enormous, but the direct genetic impact would have been negligible.

This same difficulty of relative proportions frustrates any attempt to apply in China an evolutionary model similar to the one that Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending have persuasively suggested for the evolution of high intelligence among the Ashkenazi Jews of Europe. The latter group constituted a small, reproductively isolated population overwhelmingly concentrated in the sorts of business and financial activity that would have strongly favored more intelligent individuals, and one with insignificant gene-flow from the external population not undergoing such selective pressure. By contrast, there is no evidence that successful Chinese merchants or scholars were unwilling to take brides from the general population, and any reasonable rate of such intermarriage each generation would have totally swamped the genetic impact of mercantile or scholarly success. If we are hoping to find any rough parallel to the process that Clark hypothesizes for Britain, we must concentrate our attention on the life circumstances of China’s broad rural peasantry—well over 90 percent of the population during all these centuries—just as the aforementioned 19th-century observers had generally done.

In fact, although Western writers tended to focus on China’s horrific poverty above all else, traditional Chinese society actually possessed certain unusual or even unique characteristics that may help account for the shaping of the Chinese people. Perhaps the most important of these was the near total absence of social caste and the extreme fluidity of economic class.

Feudalism had ended in China a thousand years before the French Revolution, and nearly all Chinese stood equal before the law. The “gentry”—those who had passed an official examination and received an academic degree—possessed certain privileges and the “mean people”—prostitutes, entertainers, slaves, and various other degraded social elements—suffered under legal discrimination. But both these strata were minute in size, with each usually amounting to less than 1 percent of the general population, while “the common people”—everyone else, including the peasantry—enjoyed complete legal equality.

However, such legal equality was totally divorced from economic equality, and extreme gradations of wealth and poverty were found in every corner of society, down to the smallest and most homogenous village. During most of the 20th century, the traditional Marxian class analysis of Chinese rural life divided the population according to graduated wealth and degree of “exploitative” income: landlords, who obtained most or all of their income from rent or hired labor; rich, middle, and poor peasants, grouped according to decreasing wealth and rental income and increasing tendency to hire out their own labor; and agricultural laborers, who owned negligible land and obtained nearly all their income from hiring themselves out to others.

In hard times, these variations in wealth might easily mean the difference between life and death, but everyone acknowledged that such distinctions were purely economic and subject to change: a landlord who lost his land would become a poor peasant; a poor peasant who came into wealth would be the equal of any landlord. During its political struggle, the Chinese Communist Party claimed that landlords and rich peasants constituted about 10 percent of the population and possessed 70–80 percent of the land, while poor peasants and hired laborers made up the overwhelming majority of the population and owned just 10–15 percent of the land. Neutral observers found these claims somewhat exaggerated for propagandistic purposes, but not all that far from the harsh reality.

Complete legal equality and extreme economic inequality together fostered one of the most unrestrained free-market systems known to history, not only in China’s cities but much more importantly in its vast countryside, which contained nearly the entire population. Land, the primary form of wealth, was freely bought, sold, traded, rented out, sub-leased, or mortgaged as loan collateral. Money-lending and food-lending were widely practiced, especially during times of famine, with usurious rates of interest being the norm, often in excess of 10 percent per month compounded. In extreme cases, children or even wives might be sold for cash and food. Unless aided by relatives, peasants without land or money routinely starved to death. Meanwhile, the agricultural activity of more prosperous peasants was highly commercialized and entrepreneurial, with complex business arrangements often the norm.

For centuries, a central fact of daily life in rural China had been the tremendous human density, as the Middle Kingdom’s population expanded from 65 million to 430 million during the five centuries before 1850, eventually forcing nearly all land to be cultivated to maximum efficiency. Although Chinese society was almost entirely rural and agricultural, Shandong province in 1750 had well over twice the population density of the Netherlands, the most urbanized and densely populated part of Europe, while during the early years of the Industrial Revolution, England’s population density was only one-fifth that of Jiangsu province.

Chinese agricultural methods had always been exceptionally efficient, but by the 19th century, the continuing growth of the Chinese population had finally caught and surpassed the absolute Malthusian carrying-capacity of the farming system under its existing technical and economic structure. Population growth was largely held in check by mortality (including high infant mortality), decreased fertility due to malnutrition, disease, and periodic regional famines that killed an average of 5 percent of the population. Even the Chinese language came to incorporate the centrality of food, with the traditional words of greeting being “Have you eaten?” and the common phrase denoting a wedding, funeral, or other important social occasion being “to eat good things.”

The cultural and ideological constraints of Chinese society posed major obstacles to mitigating this never-ending human calamity. Although impoverished Europeans of this era, male and female alike, often married late or not at all, early marriage and family were central pillars of Chinese life, with the sage Mencius stating that to have no children was the worst of unfilial acts; indeed, marriage and anticipated children were the mark of adulthood. Furthermore, only male heirs could continue the family name and ensure that oneself and one’s ancestors would be paid the proper ritual respect, and multiple sons were required to protect against the vagaries of fate. On a more practical level, married daughters became part of their husband’s household, and only sons could ensure provision for one’s old age.

Nearly all peasant societies sanctify filial loyalty, marriage, family, and children, while elevating sons above daughters, but in traditional China these tendencies seem to have been especially strong, representing a central goal and focus of all daily life beyond bare survival. Given the terrible poverty, cruel choices were often made, and female infanticide, including through neglect, was the primary means of birth control among the poor, leading to a typical shortfall of 10–15 percent among women of marriageable age. Reproductive competition for those remaining women was therefore fierce, with virtually every woman marrying, generally by her late teens. The inevitable result was a large and steady natural increase in the total population, except when constrained by various forms of increased mortality.

The vast majority of Chinese might be impoverished peasants, but for those with ability and luck, the possibilities of upward mobility were quite remarkable in what was an essentially classless society. The richer strata of each village possessed the wealth to give their most able children a classical education in hopes of preparing them for the series of official examinations. If the son of a rich peasant or petty landlord were sufficiently diligent and intellectually able, he might pass such an examination and obtain an official degree, opening enormous opportunities for political power and wealth.

For the Ming (1368–1644) and Ch’ing (1644–1911) dynasties, statistics exist on the social origins of the chin-shih class, the highest official rank, and these demonstrate a rate of upward mobility unmatched by almost any Western society, whether modern or premodern. Over 30 percent of such elite degree-holders came from commoner families that for three previous generations had produced no one of high official rank, and in the data from earlier centuries, this fraction of “new men” reached a high of 84 percent. Such numbers far exceed the equivalent figures for Cambridge University during all the centuries since its foundation, and would probably seem remarkable at America’s elite Ivy League colleges today or in the past. Meanwhile, downward social mobility was also common among even the highest families. As a summary statistic, across the six centuries of these two dynasties less than 6 percent of China’s ruling elites came from the ruling elites of the previous generation.

The founding philosophical principle of the modern Western world has been the “Equality of Man,” while that of Confucianist China was the polar opposite belief in the inherent inequality of men. Yet in reality, the latter often seemed to fulfill better the ideological goals of the former. Frontier America might have had its mythos of presidents born in log-cabins, but for many centuries a substantial fraction of the Middle Kingdom’s ruling mandarins did indeed come from rural rice-paddies, a state of affairs that would have seemed almost unimaginable in any European country until the Age of Revolution, and even long afterward.

Such potential for elevation into the ruling Chinese elite was remarkable, but a far more important factor in the society was the open possibility of local economic advancement for the sufficiently enterprising and diligent rural peasant. Ironically enough, a perfect description of such upward mobility was provided by Communist revolutionary leader Mao Zedong, who recounted how his father had risen from being a landless poor peasant to rich peasant status:

My father was a poor peasant and while still young was obliged to join the army because of heavy debts. He was a soldier for many years. Later on he returned to the village where I was born, and by saving carefully and gathering together a little money through small trading and other enterprise he managed to buy back his land.

As middle peasants then my family owned fifteen mou [about 2.5 acres] of land. On this they could raise sixty tan of rice a year. The five members of the family consumed a total of thirty-five tan—that is, about seven each—which left an annual surplus of twenty-five tan. Using this surplus, my father accumulated a little capital and in time purchased seven more mou, which gave the family the status of ‘rich’ peasants. We could then raise eighty-four tan of rice a year.

When I was ten years of age and the family owned only fifteen mou of land, the five members of the family consisted of my father, mother, grandfather, younger brother, and myself. After we had acquired the additional seven mou, my grandfather died, but there came another younger brother. However, we still had a surplus of forty-nine tan of rice each year, and on this my father prospered.

At the time my father was a middle peasant he began to deal in grain transport and selling, by which he made a little money. After he became a ‘rich’ peasant, he devoted most of his time to that business. He hired a full-time farm laborer, and put his children to work on the farm, as well as his wife. I began to work at farming tasks when I was six years old. My father had no shop for his business. He simply purchased grain from the poor farmers and then transported it to the city merchants, where he got a higher price. In the winter, when the rice was being ground, he hired an extra laborer to work on the farm, so that at that time there were seven mouths to feed. My family ate frugally, but had enough always.

Mao’s account gives no indication that he regarded his family’s rise as extraordinary in any way; his father had obviously done well, but there were probably many other families in Mao’s village that had similarly improved their lot during the course of a single generation. Such opportunities for rapid social mobility would have been almost impossible in any of the feudal or class-ridden societies of the same period, in Europe or most other parts of the world.

However, the flip-side of possible peasant upward mobility was the far greater likelihood of downward mobility, which was enormous and probably represented the single most significant factor shaping the modern Chinese people. Each generation, a few who were lucky or able might rise, but a vast multitude always fell, and those families near the bottom simply disappeared from the world. Traditional rural China was a society faced with the reality of an enormous and inexorable downward mobility: for centuries, nearly all Chinese ended their lives much poorer than had their parents.

The strong case for such downward mobility was demonstrated a quarter century ago by historian Edwin E. Moise, whose crucial article on the subject has received far less attention than it deserves, perhaps because the intellectual climate of the late 1970s prevented readers from drawing the obvious evolutionary implications.

In many respects, Moise’s demographic analysis of China eerily anticipated that of Clark for England, as he pointed out that only the wealthier families of a Chinese village could afford the costs associated with obtaining wives for their sons, with female infanticide and other factors regularly ensuring up to a 15 percent shortfall in the number of available women. Thus, the poorest village strata usually failed to reproduce at all, while poverty and malnourishment also tended to lower fertility and raise infant mortality as one moved downward along the economic gradient. At the same time, the wealthiest villagers sometimes could afford multiple wives or concubines and regularly produced much larger numbers of surviving offspring. Each generation, the poorest disappeared, the less affluent failed to replenish their numbers, and all those lower rungs on the economic ladder were filled by the downwardly mobile children of the fecund wealthy.

This fundamental reality of Chinese rural existence was certainly obvious to the peasants themselves and to outside observers, and there exists an enormous quantity of anecdotal evidence describing the situation, whether gathered by Moise or found elsewhere, as illustrated by a few examples:

‘How could any man in our village claim that his family had been poor for three generations? If a man is poor, then his son can’t afford to marry; and if his son can’t marry, there can’t be a third generation.’

… Because of the marked shortage of women, there was always a great number of men without wives at all. This included the overwhelming majority of long-term hired laborers… The poorest families died out, being unable to arrange marriages for their sons. The future generations of poor were the descendants of bankrupted middle and rich peasants and landlords.

… Further down the economic scale there were many families with unmarried sons who had already passed the customary marriage age, thus limiting the size of the family. Wong Mi was a case in point. He was already twenty-three, with both of his parents in their mid-sixties; but since the family was able to rent only an acre of poor land and could not finance his marriage, he lived with the old parents, and the family consisted of three members. Wong Chun, a landless peasant in his forties, had been in the same position when he lived with his aged parents ten years before, and now, both parents having died, he lived alone. There were ten or fifteen families in the village with single unmarried sons.

… As previously mentioned, there were about twenty families in Nanching that had no land at all and constituted the bottom group in the village’s pyramid of land ownership. A few of these families were tenant farmers, but the majority, since they could not finance even the buying of tools, fertilizer, and seeds, worked as “long-term” agricultural laborers on an annual basis. As such, they normally were paid about 1,000 catties of unhusked rice per year and board and room if they owned no home. This income might equal or even exceed what they might have wrested from a small rented farm, but it was not enough to support a family of average size without supplementary employment undertaken by other members of the family. For this reason, many of them never married, and the largest number of bachelors was to be found among landless peasants. Wong Tu-en, a landless peasant working for a rich peasant for nearly ten years, was still a “bare stick” (unmarried man) in his fifties; and there were others in the village like him. They were objects of ridicule and pity in the eyes of the villagers, whose life [sic] centered upon the family.

Furthermore, the forces of downward mobility in rural Chinese society were greatly accentuated by fenjia, the traditional system of inheritance, which required equal division of property among all sons, in sharp contrast to the practice of primogeniture commonly found in European countries.

If most or all of a father’s property went to the eldest son, then the long-term survival of a reasonably affluent peasant family was assured unless the primary heir were a complete wastrel or encountered unusually bad fortune. But in China, cultural pressures forced a wealthy man to do his best to maximize the number of his surviving sons, and within the richer strata of a village it was not uncommon for a man to leave two, three, or even more male heirs, compelling each to begin his economic independence with merely a fraction of his father’s wealth. Unless they succeeded in substantially augmenting their inheritance, the sons of a particularly fecund rich landlord might be middle peasants—and his grandchildren, starving poor peasants. Families whose elevated status derived from a single fortuitous circumstance or a transient trait not deeply rooted in their behavioral characteristics therefore enjoyed only fleeting economic success, and poverty eventually culled their descendants from the village.

The members of a successful family could maintain their economic position over time only if in each generation large amounts of additional wealth were extracted from their land and their neighbors through high intelligence, sharp business sense, hard work, and great diligence. The penalty for major business miscalculations or lack of sufficient effort was either personal or reproductive extinction. As American observer William Hinton graphically described:

Security, relative comfort, influence, position, and leisure [were] maintained amidst a sea of the most dismal and frightening poverty and hunger—a poverty and hunger which at all times threatened to engulf any family which relaxed its vigilance, took pity on its poor neighbors, failed to extract the last copper of rent and interest, or ceased for an instant the incessant accumulation of grain and money. Those who did not go up went down, and those who went down often went to their deaths or at least to the dissolution and dispersal of their families.

However, under favorable circumstances, a family successful in business might expand its numbers from generation to generation until it gradually squeezed out all its less competitive neighbors, with its progeny eventually constituting nearly the entire population of a village. For example, a century after a couple of poor Yang brothers arrived in a region as farm laborers, their descendants had formed a clan of 80–90 families in one village and the entire population of a neighboring one. In a Guangdong village, a merchant family named Huang arrived and bought land, growing in numbers and land ownership over the centuries until their descendants replaced most of the other families, which became poor and ultimately disappeared, while the Huangs eventually constituted 74 percent of the total local population, including a complete mix of the rich, middle, and poor.

In many respects, the Chinese society portrayed by our historical and sociological sources seems an almost perfect example of the sort of local environment that would be expected to produce a deep imprint upon the characteristics of its inhabitants. Even prior to the start of this harsh development process, China had spent thousands of years as one of the world’s most advanced economic and technological civilizations. The socioeconomic system established from the end of the sixth century A.D. onward then remained largely stable and unchanged for well over a millennium, with the sort of orderly and law-based society that benefited those who followed its rules and ruthlessly weeded out the troublemaker. During many of those centuries, the burden of overpopulation placed enormous economic pressure on each family to survive, while a powerful cultural tradition emphasized the production of surviving offspring, especially sons, as the greatest goal in life, even if that result might lead to the impoverishment of the next generation. Agricultural efficiency was remarkably high but required great effort and diligence, while the complexities of economic decision-making—how to manage land, crop selection, and investment decisions—were far greater than those faced by the simple peasant serf found in most other parts of the world, with the rewards for success and the penalties for failure being extreme. The sheer size and cultural unity of the Chinese population would have facilitated the rapid appearance and spread of useful innovations, including those at the purely biological level.

It is important to recognize that although good business ability was critical for the long-term success of a line of Chinese peasants, the overall shaping constraints differed considerably from those that might have affected a mercantile caste such as the Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern Europe or the Parsis of India. These latter groups occupied highly specialized economic niches in which a keen head for figures or a ruthless business sense might have been all that was required for personal success and prosperity. But in the world of rural Chinese villages, even the wealthier elements usually spent the majority of the lives in backbreaking labor, working alongside their families and their hired men in the fields and rice paddies. Successful peasants might benefit from a good intellect, but they also required the propensity for hard manual toil, determination, diligence, and even such purely physical traits as resistance to injury and efficiency in food digestion. Given such multiple selective pressures and constraints, we would expect the shift in the prevalence of any single one of these traits to be far slower than if it alone determined success, and the many centuries of steady Chinese selection across the world’s largest population would have been required to produce any substantial result.

The impact of such strong selective forces obviously manifests at multiple levels, with cultural software being far more flexible and responsive than any gradual shifts in innate tendencies, and distinguishing between evidence of these two mechanisms is hardly a trivial task. But it seems quite unlikely that the second, deeper sort of biological human change would not have occurred during a thousand years or more of these relentlessly shaping pressures, and simply to ignore or dismiss such an important possibility is unreasonable. Yet that seems to have been the dominant strain of Western intellectual belief for the last two or three generations.

Sometimes the best means of recognizing one’s ideological blinders is to consider seriously the ideas and perspectives of alien minds that lack them, and in the case of Western society these happen to include most of our greatest intellectual figures from 80 or 90 years ago, now suddenly restored to availability by the magic of the Internet. Admittedly, in some respects these individuals were naïve in their thinking or treated various ideas in crude fashion, but in many more cases their analyses were remarkably acute and scientifically insightful, often functioning as an invaluable corrective to the assumed truths of the present. And in certain matters, notably predicting the economic trajectory of the world’s largest country, they seem to have anticipated developments that almost none of their successors of the past 50 years ever imagined. This should certainly give us pause.

Consider also the ironic case of Bruce Lahn, a brilliant Chinese-born genetics researcher at the University of Chicago. In an interview a few years ago, he casually mentioned his speculation that the socially conformist tendencies of most Chinese people might be due to the fact that for the past 2,000 years the Chinese government had regularly eliminated its more rebellious subjects, a suggestion that would surely be regarded as totally obvious and innocuous everywhere in the world except in the West of the past half century or so. Not long before that interview, Lahn had achieved great scientific acclaim for his breakthrough discoveries on the possible genetic origins of human civilization, but this research eventually provoked such heated controversy that he was dissuaded from continuing it.

Yet although Chinese researchers living in America willingly conform to American ideological restrictions, this is not the case with Chinese researchers in China itself, and it is hardly surprising that BGI—the Beijing Genomics Institute—has become the recognized world leader in cutting-edge human genetics research. This is despite the billions spent by its American counterparts, which must operate within a much more circumscribed framework of acceptable ideas.

During the Cold War, the enormous governmental investments of the Soviet regime in many fields produced nothing, since they were based on a model of reality that was both unquestionable and also false. The growing divergence between that ideological model and the real world eventually doomed the USSR, whose vast and permanent bulk blew away in a sudden gust of wind two decades ago. American leaders should take care that they do not stubbornly adhere to scientifically false doctrines that will lead our own country to risk a similar fate.

Ron Unz is publisher of The American Conservative.