战争注定:中美能否摆脱修昔底德陷阱?

2017 年 5 月 30 日

作者:格雷厄姆·艾利森 2015 年 9 月 24 日

哈佛大学约翰·F·肯尼迪政府学院道格拉斯·狄龙政府学教授。

中国和美国正在走向一场双方都不希望发生的战争。原因是修昔底德陷阱,这是一种致命的结构性压力模式,当崛起的国家挑战统治国家时就会产生这种结构性压力。 这种现象与历史本身一样古老。 关于摧毁古希腊的伯罗奔尼撒战争,历史学家修昔底德解释说:“正是雅典的崛起以及由此给斯巴达灌输的恐惧,使得战争不可避免。” 过去 500 年来,这种情况已经发生了十六次。 其中十二个地区爆发了战争。 如今,随着势不可挡的中国逼近不可撼动的美国,习近平和特朗普都承诺让自己的国家“再次伟大”,第十七起案件显得严峻。 除非中国愿意缩减其野心,或者华盛顿能够接受成为太平洋地区的第二大国家,否则贸易冲突、网络攻击或海上事故可能很快就会升级为全面战争。

哈佛大学著名学者格雷厄姆·艾利森在《注定一战》一书中解释了为什么修昔底德陷阱是理解二十一世纪中美关系的最佳镜头。 通过不可思议的历史相似之处和战争场景,他展示了我们距离不可想象的事物有多近。 然而,艾利森强调战争并非不可避免,他还揭示了过去冲突中的大国如何维持和平,以及美国和中国今天必须采取哪些痛苦的步骤来避免灾难。

修昔底德陷阱:中美是否会走向战争?

作者:格雷厄姆·艾利森 2015 年 9 月 24 日

哈佛大学约翰·F·肯尼迪政府学院道格拉斯·狄龙政府学教授。

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/09/united-states-china-war-thucydides-trap/406756/

过去16起崛起大国与统治大国对抗的案例中,有12起都是流血的结果。

当巴拉克·奥巴马(Barack Obama)本周在中国国家主席首次对美国进行国事访问期间与习近平会面时,有一个项目可能不会出现在他们的议程上:美国和中国可能会在未来十年内陷入战争。 在政策圈子里,这似乎不太可能,也是不明智的。

然而 100 年后,第一次世界大战发人深省地提醒我们,人类也有犯下愚蠢的行为。 当我们说战争是“不可思议的”时,这是关于世界上可能发生的事情的陈述,还是仅仅关于我们有限的头脑可以想象的事情? 1914 年,很少有人能想象屠杀的规模如此之大,以至于需要一个新的类别:世界大战。 四年后战争结束时,欧洲一片废墟:德皇去世,奥匈帝国解体,俄罗斯沙皇被布尔什维克推翻,法国一代人流血,英国失去了青春和财富。 欧洲作为世界政治中心的一个千年戛然而止。

享受一年无限制地访问大西洋 — 包括我们网站和应用程序上的每个故事、订阅者新闻通讯等等。

对于这一代人来说,全球秩序的决定性问题是中国和美国能否逃脱修昔底德陷阱。 这位希腊历史学家的比喻提醒我们,当崛起的大国与统治大国竞争时,随之而来的危险就如雅典挑战古希腊的斯巴达,或者一个世纪前的德国挑战英国。 哈佛贝尔弗科学与国际事务中心的一个团队在分析历史记录后得出结论,大多数此类竞赛的结局往往都很糟糕,尤其是对两国而言。 过去500年的16个案例中有12个的结果是战争。 当各方避免战争时,不仅挑战者而且被挑战者都需要在态度和行动上进行巨大而痛苦的调整。

根据目前的轨迹,未来几十年美国和中国之间爆发战争不仅是可能的,而且比目前认识到的可能性要大得多。 事实上,从历史记录来看,战争的可能性更大。 此外,当前对中美关系固有危险的低估和误解在很大程度上加剧了这些危险。 与修昔底德陷阱相关的一个风险是,一切照旧——不仅仅是意外的、非同寻常的事件——可能引发大规模冲突。 当一个崛起的国家威胁要取代一个统治国家时,本来可以遏制的标准危机,比如 1914 年大公被暗杀,可能会引发一连串的反应,进而产生任何一方都不会选择的结果 。

然而,战争并非不可避免。 我们审查的 16 起案件中有 4 起没有以流血告终。 这些成功和失败都为当今的世界领导人提供了相关的教训。 逃离陷阱需要付出巨大的努力。 正如习近平本人周二访问西雅图时所说,“世界上不存在所谓的修昔底德陷阱。 但如果大国一再犯战略误判的错误,就可能给自己制造这样的陷阱。”

** **

2400多年前,雅典历史学家修昔底德提出了有力的见解:“正是雅典的崛起,以及由此在斯巴达引发的恐惧,使得战争不可避免。” 其他人则指出了引发伯罗奔尼撒战争的一系列原因。 但修昔底德直击问题的核心,重点关注两个对手之间权力平衡的迅速转变所造成的不可阻挡的结构性压力。 请注意,修昔底德指出了这一动态的两个关键驱动因素:一方面,新兴大国日益增长的权利、对其重要性的认识以及对更大发言权和影响力的需求,另一方面是由此产生的恐惧、不安全感和捍卫现状的决心。 另一方面,在既定权力中。

在他于公元前五世纪所写的案例中,雅典在半个多世纪的时间里成为了文明的尖塔,在哲学、历史、戏剧、建筑、民主和海军实力方面取得了进步。 这震惊了斯巴达,一个世纪以来,斯巴达一直是伯罗奔尼撒半岛的主要陆地强国。 在修昔底德看来,雅典的立场是可以理解的。 随着其影响力的增强,它的自信心、对过去不公正现象的认识、对不尊重事件的敏感度以及对先前安排进行修改以反映新的权力现实的坚持也在增强。 修昔底德解释说,这也是自然的,斯巴达将雅典的姿态解读为不合理、忘恩负义,并且威胁到其所建立的体系——而雅典正是在这个体系中繁荣发展的。

修昔底德记录了相对实力的客观变化,但他也关注雅典和斯巴达领导人对变化的看法,以及这如何导致各自加强与其他国家的联盟,以期制衡对方。 但纠缠是双向的。 (正是出于这个原因,乔治·华盛顿曾告诫美国要提防“纠缠的联盟”。)当二线城邦科林斯和科西拉(现为科孚岛)之间爆发冲突时,斯巴达觉得有必要向科林斯进军。 防御,这让雅典别无选择,只能支持其盟友。 随后发生了伯罗奔尼撒战争。 30年后,战争结束时,斯巴达成为名义上的胜利者。 但这两个国家都已成为废墟,使希腊容易受到波斯人的攻击。

** **

欧洲世界大战爆发前八年,英国国王爱德华七世问他的首相,为什么英国政府对他的侄子德皇威廉二世的德国变得如此不友好,而不是继续关注美国,他认为美国是更大的挑战 。 首相指示外交部首席德国观察员艾尔·克罗撰写一份备忘录来回答国王的问题。 克罗于 1907 年元旦发表了他的备忘录。这份文件是外交史上的瑰宝。

克罗分析的逻辑与修昔底德的见解相呼应。 正如亨利·基辛格在《论中国》中所阐述的那样,他的核心问题是:英国和德国之间日益增长的敌意更多地源于德国的能力还是德国的行为? 克罗的说法略有不同:德国追求“政治霸权和海上优势”是否对“邻国的独立以及最终英国的存在”构成了生存威胁?

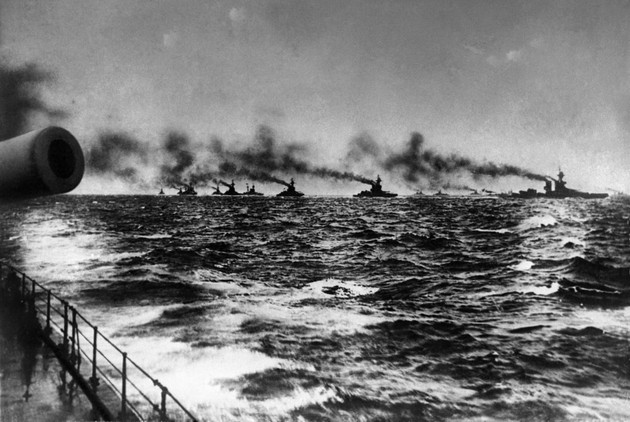

1916 年日德兰海战中,英国大舰队正前往与德意志帝国海军舰队会合 (美联社)

克罗的回答毫不含糊:能力是关键。 随着德国经济超越英国,德国不仅会发展欧洲大陆最强大的军队。 它还将很快“建立一支尽可能强大的海军”。 换句话说,基辛格写道,“一旦德国取得了海上霸权……无论德国的意图如何,这本身就会对英国构成客观威胁,并且与大英帝国的存在不相容。”

读完这份备忘录三年后,爱德华七世去世了。 参加他葬礼的人包括两位“主祭”——爱德华的继任者乔治五世和德国皇帝威廉——以及代表美国的西奥多·罗斯福。 有一次,罗斯福(一位热衷于海军力量的学生和美国海军建设的主要倡导者)问威廉是否会考虑暂停德英海军军备竞赛。 德皇回答说,德国坚定不移地致力于拥有一支强大的海军。 但正如他继续解释的那样,德国和英国之间的战争简直是不可想象的,因为“我很大程度上是在英国长大的;我是在英国长大的”。 我觉得自己有一部分是英国人。 除了德国之外,我比其他任何国家都更关心英格兰。” 然后强调:“我喜欢英格兰!”

不管冲突看起来多么难以想象,对所有参与者造成的潜在后果有多么灾难性,领导人甚至血亲之间的文化同理心有多么深厚,以及经济上相互依存的国家有多么深,这些因素都不足以阻止 1914 年或今天的战争。

事实上,在过去 500 年的 16 起案例中,有 12 起新兴国家的相对实力发生迅速变化,威胁要取代统治国家,其结果就是战争。 如下表所示,过去半个世纪欧洲和亚洲的统治权斗争在一个共同的故事情节上出现了一系列的变化。

修昔底德案例研究

哈佛大学贝尔弗科学与国际事务中心

(有关这 16 个案例的摘要以及选择它们的方法,以及登记案例的添加、删除、修改和分歧的论坛,请访问哈佛贝尔弗中心的修昔底德陷阱案例档案。对于该项目的第一阶段 ,我们贝尔弗中心通过遵循主要历史记录的判断来识别“统治”和“崛起”权力,抵制对事件提供原创或特殊解释的诱惑。这些历史根据其传统使用“崛起”和“统治” 定义,通常强调相对 GDP 和军事实力的快速变化。第一轮分析中的大多数案例来自后威斯特伐利亚时期的欧洲。)

当崛起的革命法国挑战英国的海洋统治地位和欧洲大陆的力量平衡时,英国于1805年摧毁了拿破仑·波拿巴的舰队,随后派遣军队前往欧洲大陆

在西班牙和滑铁卢击败了他的军队。 当奥托·冯·俾斯麦寻求统一不断争吵的新兴德国国家时,与共同对手法国的战争被证明是动员民众支持他的使命的有效工具。 1868 年明治维新后,快速现代化的日本经济和军事设施挑战了中国和俄罗斯在东亚的主导地位,导致与两国发生战争,日本由此成为该地区的主导力量。

当然,每个案例都是独一无二的。 关于第一次世界大战原因的持续争论提醒我们,每种原因都存在相互竞争的解释。 哈佛大学的欧内斯特·梅(Ernest May)是一位伟大的国际历史学家,他教导说,当我们试图从历史中推理时,我们应该对我们比较的案例之间的差异和相似之处同样敏感。 (事实上,在他的历史推理 101 课上,梅会拿一张纸,在页面中间画一条线,将一列标记为“相似”,将另一列标记为“不同”,然后在纸上填写至少一个 各半打。)尽管如此,修昔底德承认存在许多差异,但他引导我们找到了一个强大的共同点。

** **

这个时代最突出的地缘战略挑战不是暴力的伊斯兰极端分子或复兴的俄罗斯。 这是中国的崛起将对美国领导的国际秩序产生的影响,该秩序在过去70年里提供了前所未有的大国和平与繁荣。 正如新加坡已故领导人李光耀所言,“中国对世界平衡的破坏如此之大,世界必须找到新的平衡。 不可能假装这只是另一个大玩家。 这是世界历史上最伟大的球员。” 中国的崛起大家都知道。 我们很少有人意识到它的重要性。 历史上从来没有一个国家在如此多的权力维度上崛起得如此之远、如此之快。 用捷克前总统瓦茨拉夫·哈维尔的话来说,这一切发生得如此之快,以至于我们还没来得及感到惊讶。

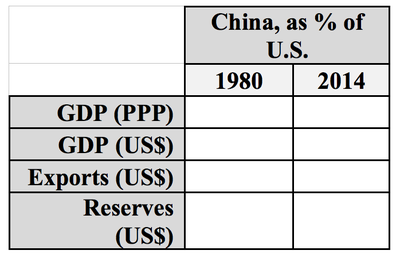

我在哈佛关于这个主题的演讲以一个测验开始,要求学生将 1980 年的中国和美国与今天的排名进行比较。 请读者填空。

测验:填空

哈佛贝尔弗中心

第一栏的答案:1980年,按购买力平价衡量,中国GDP占美国的10%; 按当前美元汇率计算占GDP的7%; 及其出口额的 6%。 与此同时,中国持有的外汇仅为美国储备规模的六分之一。 第二栏的答案是:到2014年,这些数字占GDP的101%; 按美元汇率计算为 60%; 占出口的 106%。 如今中国的外汇储备是美国的28倍。

在一代人的时间里,一个从未出现在任何国际排行榜上的国家已经跻身顶级行列。 1980年,中国经济规模还小于荷兰。 去年,中国GDP的增长增量大致相当于整个荷兰经济的增量。

我的测验中的第二个问题问学生:中国能成为第一吗? 中国什么时候才能超越美国,成为世界上最大的经济体、全球增长的主要引擎或最大的奢侈品市场?

中国能成为第一吗?

制造商:

出口商:

贸易国:

节省者:

美国国债持有人:

外商直接投资目的地:

能源消耗者:

石油进口国:

碳排放量:

钢铁生产商:

汽车市场:

智能手机市场:

电商市场:

奢侈品市场:

互联网用户:

最快的超级计算机:

外汇储备持有者:

首次公开募股的来源:

全球增长的主要引擎:

经济:

大多数人惊讶地发现,在这20个指标中,中国每一项都已经超过了美国。

中国能否在未来十年乃至更长时间内保持数倍于美国的经济增长率? 如果确实如此,其现任领导人是否认真考虑取代美国成为亚洲的主导力量? 中国是否会步日本和德国的后尘,在美国过去七十年建立的国际秩序中成为负责任的利益相关者? 这些问题的答案显然无人知晓。

但如果说有人的预测值得关注的话,那就是李光耀的预测。李光耀是全球首席中国问题观察家,也是自邓小平以来中国领导人的导师。 这位新加坡创始人在三月去世前曾表示,未来十年及更长时间内,中国经济继续以美国几倍的速度增长的可能性为“五分之四”。 当被问及中国领导人是否认真考虑在可预见的未来取代美国成为亚洲头号强国时,李直接回答道:“当然。 为什么不……他们怎么可能不渴望成为亚洲第一,乃至世界第一呢?” 以及接受美国设计和领导的国际秩序中的地位

他说绝对不会:“中国希望成为中国并被接受为中国,而不是作为西方的荣誉成员。”

** **

美国人倾向于教导别人为什么他们应该“更像我们”。 在敦促中国效仿美国的同时,我们美国人是否应该谨慎行事?

当美国在1890年代成为西半球的主导力量时,它的表现如何? 未来的总统西奥多·罗斯福代表了一个对未来 100 年将是美国世纪充满信心的国家。 从 1895 年美国国务卿宣布美国“在这片大陆上拥有主权”开始的十多年来,美国解放了古巴; 以战争威胁英国和德国,迫使它们接受美国在委内瑞拉和加拿大争端上的立场; 支持分裂哥伦比亚的叛乱,创建一个新的巴拿马国(巴拿马立即给予美国让步修建巴拿马运河); 并试图推翻墨西哥政府,该政府得到英国的支持和伦敦银行家的资助。 在接下来的半个世纪里,美国军队在 30 多个不同的场合对“我们的半球”进行干预,以有利于美国人的条件解决经济或领土争端,或者驱逐他们认为不可接受的领导人。

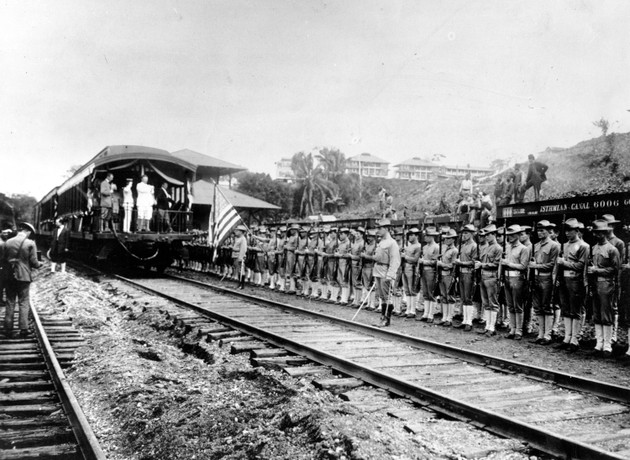

1906 年,西奥多·罗斯福与美军在巴拿马运河区(维基媒体)

例如,1902年,当英国和德国船只试图实施海上封锁,迫使委内瑞拉偿还债务时,罗斯福警告两国,如果他们不撤回其债务,他将“在必要时采取武力干预”。 船舶。 英国和德国被说服撤退,并在海牙以美国满意的方式解决争端。 次年,当哥伦比亚拒绝将巴拿马运河区租给美国时,美国资助了巴拿马分裂分子,在巴拿马新政府宣布独立后数小时内就承认了它,并派遣海军陆战队保卫这个新国家。 罗斯福为美国的干预辩护,理由是“在道德上是合理的,因此在法律上也是合理的”。 此后不久,巴拿马“永久”授予美国对运河区的权利。

** **

1978年,当邓小平发起中国快速进军市场时,他宣布了一项被称为“躲藏”的政策。 中国在海外最需要的是稳定和市场准入。 因此,中国人会“等待时机,隐藏我们的能力”,中国军官有时将其解释为“先强后报”。

随着中国新任最高领导人习近平的上任,“躲躲闪闪”的时代结束了。 习近平十年任期已近三年,他的行动速度和雄心壮志令国内同仁和海外中国观察家感到震惊。 在国内,他绕过了七人常委会的统治,而是将权力巩固在自己手中。 通过重申共产党对政治权力的垄断,结束了对民主化的挑衅; 并试图将中国的增长引擎从出口导向型经济转变为国内消费驱动型经济。 在海外,他奉行更加积极的中国外交政策,在促进国家利益方面越来越自信。

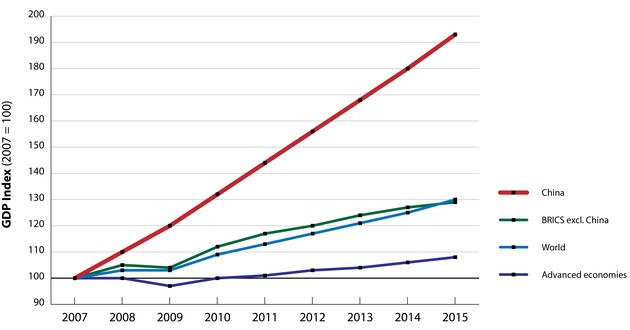

虽然西方媒体被“中国经济放缓”的故事情节所吸引,但很少有人停下来注意到中国较低的增长率仍然是美国的三倍多。 中国以外的许多观察家都忽略了自2008年金融危机和大衰退以来的七年里中国经济表现与其竞争对手之间的巨大差距。 这次冲击几乎导致所有其他主要经济体动摇和衰退。 中国从未错过增长的一年,平均增长率保持在8%以上。 事实上,自金融危机以来,全球经济增长近 40% 只发生在一个国家:中国。 下图显示了中国的增长与金砖国家新兴经济体、发达经济体和世界其他国家的增长相比。 与 2007 年 100 的共同指数相比,差异是巨大的。

国内生产总值,2007 — 2015

哈佛贝尔弗中心/国际货币基金组织世界经济展望

如今,以公民在自己国家可以购买的商品和服务数量(购买力平价)来衡量,中国已取代美国成为世界上最大的经济体。

习近平所说的“中国梦”表达了亿万中国人的最深切愿望,不仅要富,还要强。 中国文明信条的核心是相信——或者说自负——中国是宇宙的中心。 在人们不断重复的叙述中,中国一个世纪的衰弱导致了西方殖民主义者和日本的剥削和民族羞辱。

在北京看来,中国现在正在恢复其应有的地位,其实力值得中国核心利益的承认和尊重。

一幅木版画描绘了第一次中日战争。 (丰原近信/维基媒体)

去年11月,在包括中国人民解放军领导层在内的整个中国政治和外交政策机构的一次重要会议上,习近平全面概述了他对中国在世界上的作用的愿景。 自信的表现近乎傲慢。 习近平首先对多极化(即不是美国单极)和国际体系转型(即不是当前美国主导的体系)的主要历史趋势提出了本质上黑格尔式的概念。 用他的话来说,复兴的中华民族将通过对国际秩序本质的“长期”斗争来构建“新型国际关系”。 最后,他向观众保证,“世界多极化的趋势不会改变”。

鉴于客观趋势,现实主义者看到一股不可抗拒的力量正在接近不可移动的物体。 他们问,哪一种可能性较小:中国要求在东海和南海发挥比美国在20世纪初在加勒比海或大西洋更小的作用,或者美国与中国分享美国在西太平洋的主导地位 自二战以来就享受过吗?

然而,在贝尔弗中心团队分析的 16 个案例中,有 4 个案例中类似的竞争并没有以战争结束。 如果美国和中国领导人让结构性因素推动这两个伟大国家爆发战争,他们将无法躲在不可避免的外衣后面。 那些不从过去的成功和失败中吸取教训以找到更好的前进道路的人,除了他们自己之外,没有人可以责怪。

演员们装扮成红军战士,在北京纪念第二次世界大战结束 70 周年。 (金京勋/路透社)

在这一点上,讨论政策挑战的既定剧本要求转向新的战略(或至少是口号),并附上一份简短的待办事项清单,承诺与中国建立和平繁荣的关系。 将这一挑战硬塞到该模板中只会证明一件事:无法理解我试图提出的中心点。 战略家们目前最需要的不是新的战略,而是长时间的停顿反思。 如果中国崛起引发的结构性转变构成了真正修昔底德式的挑战,那么有关“再平衡”或重振“接触与对冲”的宣言,或者总统候选人呼吁采取更“强硬”或“稳健”的相同变体,那么数量 与治疗癌症的阿司匹林差不多。 未来的历史学家将把这些断言与英国、德国和俄罗斯领导人梦游到 1914 年时的遐想进行比较。

拥有13亿人口的5000年文明的崛起不是一个需要解决的问题。 这是一种病症——一种必须用一代人的时间来控制的慢性病症。 成功不仅仅需要新的口号、更频繁的总统峰会以及额外的部门工作组会议。 在没有战争的情况下管理这种关系需要两国最高层每周持续关注。 这将带来自 20 世纪 70 年代亨利·基辛格与周恩来会谈以来从未见过的深度相互理解。 最重要的是,这将意味着领导人和公众在态度和行动上发生比任何人想象的更加彻底的变化。

Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?

By Graham Allison May 30 2017

Graham Allison is the Douglas Dillon Professor of Government at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Graham Allison is a former director of the Harvard Kennedy School's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and a former U.S. assistant secretary of defense for policy and plans.

China and the United States are heading toward a war that neither side wants.

The reason is Thucydides’s Trap, a deadly pattern of structural stress that results when a rising power challenges a ruling one. This phenomenon is as old as history itself. About the Peloponnesian War that devastated ancient Greece, the historian Thucydides explained: “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” Over the past 500 years, these conditions have occurred sixteen times. War broke out in twelve of them. Today,as an unstoppable China approaches an immovable America and both Xi Jinping and Donald Trump promise to make their countries “great again,” the seventeenth case looks grim. Unless China is willing to scale back its ambitions or Washington can accept becoming number two in the Pacific, a trade conflict, cyberattack, or accident at sea could soon escalate into all-out war.

InDestined for War, the eminent Harvard scholar Graham Allison explains why Thucydides’s Trap is the best lens for understanding U.S.-China relations in the twenty-first century. Through uncanny historical parallels and war scenarios, he shows how close we are to the unthinkable. Yet, stressing that war is not inevitable, Allison also reveals how clashing powers have kept the peace in the past — and what painful steps the United States and China must take to avoid disaster today.

The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?

By Graham Allison Sept 24, 2015

The Douglas Dillon Professor of Government at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

In 12 of 16 past cases in which a rising power has confronted a ruling power, the result has been bloodshed.

When Barack Obama meets this week with Xi Jinping during the Chinese president’s first state visit to America, one item probably won’t be on their agenda: the possibility that the United States and China could find themselves at war in the next decade. In policy circles, this appears as unlikely as it would be unwise.And yet 100 years on, World War I offers a sobering reminder of man’s capacity for folly. When we say that war is “inconceivable,” is this a statement about what is possible in the world—or only about what our limited minds can conceive? In 1914, few could imagine slaughter on a scale that demanded a new category: world war. When the war ended four years later, Europe lay in ruins: the kaiser gone, the Austro-Hungarian empire dissolved, the Russian tsar overthrown by the Bolsheviks, France bled for a generation, and England shorn of its youth and treasure. A millennium in which Europe had been the political center of the world came to a crashing halt.

The defining question about global order for this generation is whether China and the United States can escape Thucydides’s Trap. The Greek historian’s metaphor reminds us of the attendant dangers when a rising power rivals a ruling power—as Athens challenged Sparta in ancient Greece, or as Germany did Britain a century ago. Most such contests have ended badly, often for both nations, a team of mine at the Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs has concluded after analyzing the historical record. In 12 of 16 cases over the past 500 years, the result was war. When the parties avoided war, it required huge, painful adjustments in attitudes and actions on the part of not just the challenger but also the challenged.

Based on the current trajectory, war between the United States and China in the decades ahead is not just possible, but much more likely than recognized at the moment. Indeed, judging by the historical record, war is more likely than not. Moreover, current underestimations and misapprehensions of the hazards inherent in the U.S.-China relationship contribute greatly to those hazards. A risk associated with Thucydides’s Trap is that business as usual—not just an unexpected, extraordinary event—can trigger large-scale conflict. When a rising power is threatening to displace a ruling power, standard crises that would otherwise be contained, like the assassination of an archduke in 1914, can initiate a cascade of reactions that, in turn, produce outcomes none of the parties would otherwise have chosen.

War, however, is not inevitable. Four of the 16 cases in our review did not end in bloodshed. Those successes, as well as the failures, offer pertinent lessons for today’s world leaders. Escaping the Trap requires tremendous effort. As Xi Jinping himself said during a visit to Seattle on Tuesday, “There is no such thing as the so-called Thucydides Trap in the world. But should major countries time and again make the mistakes of strategic miscalculation, they might create such traps for themselves.”

* * *

More than 2,400 years ago, the Athenian historian Thucydides offered a powerful insight: “It was the rise of Athens, and the fear that this inspired in Sparta, that made war inevitable.” Others identified an array of contributing causes of the Peloponnesian War. But Thucydides went to the heart of the matter, focusing on the inexorable, structural stress caused by a rapid shift in the balance of power between two rivals. Note that Thucydides identified two key drivers of this dynamic: the rising power’s growing entitlement, sense of its importance, and demand for greater say and sway, on the one hand, and the fear, insecurity, and determination to defend the status quo this engenders in the established power, on the other.

In the case about which he wrote in the fifth century B.C., Athens had emerged over a half century as a steeple of civilization, yielding advances in philosophy, history, drama, architecture, democracy, and naval prowess. This shocked Sparta, which for a century had been the leading land power on the Peloponnese peninsula. As Thucydides saw it, Athens’s position was understandable. As its clout grew, so too did its self-confidence, its consciousness of past injustices, its sensitivity to instances of disrespect, and its insistence that previous arrangements be revised to reflect new realities of power. It was also natural, Thucydides explained, that Sparta interpreted the Athenian posture as unreasonable, ungrateful, and threatening to the system it had established—and within which Athens had flourished.

Thucydides chronicled objective changes in relative power, but he also focused on perceptions of change among the leaders of Athens and Sparta—and how this led each to strengthen alliances with other states in the hopes of counterbalancing the other. But entanglement runs both ways. (It was for this reason that George Washington famously cautioned America to beware of “entangling alliances.”) When conflict broke out between the second-tier city-states of Corinth and Corcyra (now Corfu), Sparta felt it necessary to come to Corinth’s defense, which left Athens little choice but to back its ally. The Peloponnesian War followed. When it ended 30 years later, Sparta was the nominal victor. But both states lay in ruin, leaving Greece vulnerable to the Persians.

* * *

Eight years before the outbreak of world war in Europe, Britain’s King Edward VII asked his prime minister why the British government was becoming so unfriendly to his nephew Kaiser Wilhelm II’s Germany, rather than keeping its eye on America, which he saw as the greater challenge. The prime minister instructed the Foreign Office’s chief Germany watcher, Eyre Crowe, to write a memo answering the king’s question. Crowe delivered his memorandum on New Year’s Day, 1907. The document is a gem in the annals of diplomacy.

The logic of Crowe’s analysis echoed Thucydides’s insight. And his central question, as paraphrased by Henry Kissinger in On China, was the following: Did increasing hostility between Britain and Germany stem more from German capabilities or German conduct? Crowe put it a bit differently: Did Germany’s pursuit of “political hegemony and maritime ascendancy” pose an existential threat to “the independence of her neighbours and ultimately the existence of England?”

The British Grand Fleet on its way to meet the Imperial German Navy’s fleet for the Battle of Jutland in 1916 (AP)

Crowe’s answer was unambiguous: Capability was key. As Germany’s economy surpassed Britain’s, Germany would not only develop the strongest army on the continent. It would soon also “build as powerful a navy as she can afford.” In other words, Kissinger writes, “once Germany achieved naval supremacy … this in itself—regardless of German intentions—would be an objective threat to Britain, and incompatible with the existence of the British Empire.”

Three years after reading that memo, Edward VII died. Attendees at his funeral included two “chief mourners”—Edward’s successor, George V, and Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm—along with Theodore Roosevelt representing the United States. At one point, Roosevelt (an avid student of naval power and leading champion of the buildup of the U.S. Navy) asked Wilhelm whether he would consider a moratorium in the German-British naval arms race. The kaiser replied that Germany was unalterably committed to having a powerful navy. But as he went on to explain, war between Germany and Britain was simply unthinkable, because “I was brought up in England, very largely; I feel myself partly an Englishman. Next to Germany I care more for England than for any other country.” And then with emphasis: “I ADORE ENGLAND!”

However unimaginable conflict seems, however catastrophic the potential consequences for all actors, however deep the cultural empathy among leaders, even blood relatives, and however economically interdependent states may be—none of these factors is sufficient to prevent war, in 1914 or today.

In fact, in 12 of 16 cases over the last 500 years in which there was a rapid shift in the relative power of a rising nation that threatened to displace a ruling state, the result was war. As the table below suggests, the struggle for mastery in Europe and Asia over the past half millennium offers a succession of variations on a common story line.

Thucydides Case Studies

Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

(For summaries of these 16 cases and the methodology for selecting them, and for a forum to register additions, subtractions, revisions, and disagreements with the cases, please visit the Harvard Belfer Center’s Thucydides Trap Case File. For this first phase of the project, we at the Belfer Center identified “ruling” and “rising” powers by following the judgments of leading historical accounts, resisting the temptation to offer original or idiosyncratic interpretations of events. These histories use “rise” and “rule” according to their conventional definitions, generally emphasizing rapid shifts in relative GDP and military strength. Most of the cases in this initial round of analysis come from post-Westphalian Europe.)

When a rising, revolutionary France challenged Britain’s dominance of the oceans and the balance of power on the European continent, Britain destroyed Napoleon Bonaparte’s fleet in 1805 and later sent troops to the continent to defeat his armies in Spain and at Waterloo. As Otto von Bismarck sought to unify a quarrelsome assortment of rising German states, war with their common adversary, France, proved an effective instrument to mobilize popular support for his mission. After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, a rapidly modernizing Japanese economy and military establishment challenged Chinese and Russian dominance of East Asia, resulting in wars with both from which Japan emerged as the leading power in the region.

Each case is, of course, unique. Ongoing debate about the causes of the First World War reminds us that each is subject to competing interpretations. A great international historian, Harvard’s Ernest May, taught that when attempting to reason from history, we should be as sensitive to the differences as to the similarities among cases we compare. (Indeed, in his Historical Reasoning 101 class, May would take a sheet of paper, draw a line down the middle of the page, label one column “Similar” and the other “Different,” and fill in the sheet with at least a half dozen of each.) Nonetheless, acknowledging many differences, Thucydides directs us to a powerful commonality.

* * *

The preeminent geostrategic challenge of this era is not violent Islamic extremists or a resurgent Russia. It is the impact that China’s ascendance will have on the U.S.-led international order, which has provided unprecedented great-power peace and prosperity for the past 70 years. As Singapore’s late leader, Lee Kuan Yew, observed, “the size of China’s displacement of the world balance is such that the world must find a new balance. It is not possible to pretend that this is just another big player. This is the biggest player in the history of the world.” Everyone knows about the rise of China. Few of us realize its magnitude. Never before in history has a nation risen so far, so fast, on so many dimensions of power. To paraphrase former Czech President Vaclav Havel, all this has happened so rapidly that we have not yet had time to be astonished.

My lecture on this topic at Harvard begins with a quiz that asks students to compare China and the United States in 1980 with their rankings today. The reader is invited to fill in the blanks.

Quiz: Fill in the Blanks

The answers for the first column: In 1980, China had 10 percent of America’s GDP as measured by purchasing power parity; 7 percent of its GDP at current U.S.-dollar exchange rates; and 6 percent of its exports. The foreign currency held by China, meanwhile, was just one-sixth the size of America’s reserves. The answers for the second column: By 2014, those figures were 101 percent of GDP; 60 percent at U.S.-dollar exchange rates; and 106 percent of exports. China’s reserves today are 28 times larger than America’s.

In a single generation, a nation that did not appear on any of the international league tables has vaulted into the top ranks. In 1980, China’s economy was smaller than that of the Netherlands. Last year, the increment of growth in China’s GDP was roughly equal to the entire Dutch economy.

The second question in my quiz asks students: Could China become No. 1? In what year could China overtake the United States to become, say, the largest economy in the world, or primary engine of global growth, or biggest market for luxury goods?

Could China Become #1?

Manufacturer:

Exporter:

Trading nation:

Saver:

Holder of U.S. debt:

Foreign-direct-investment destination:

Energy consumer:

Oil importer:

Carbon emitter:

Steel producer:

Auto market:

Smartphone market:

E-commerce market:

Luxury-goods market:

Internet user:

Fastest supercomputer:

Holder of foreign reserves:

Source of initial public offerings:

Primary engine of global growth:

Economy:

Most are stunned to learn that on each of these 20 indicators, China has already surpassed the U.S.

Will China be able to sustain economic-growth rates several times those of the United States for another decade and beyond? If and as it does, are its current leaders serious about displacing the U.S. as the predominant power in Asia? Will China follow the path of Japan and Germany, and take its place as a responsible stakeholder in the international order that America has built over the past seven decades? The answer to these questions is obviously that no one knows.

But if anyone’s forecasts are worth heeding, it’s those of Lee Kuan Yew, the world’s premier China watcher and a mentor to Chinese leaders since Deng Xiaoping. Before his death in March, the founder of Singapore put the odds of China continuing to grow at several times U.S. rates for the next decade and beyond as “four chances in five.” On whether China’s leaders are serious about displacing the United States as the top power in Asia in the foreseeable future, Lee answered directly: “Of course. Why not … how could they not aspire to be number one in Asia and in time the world?” And about accepting its place in an international order designed and led by America, he said absolutely not: “China wants to be China and accepted as such—not as an honorary member of the West.”

* * *

Americans have a tendency to lecture others about why they should be “more like us.” In urging China to follow the lead of the United States, should we Americans be careful what we wish for?

As the United States emerged as the dominant power in the Western hemisphere in the 1890s, how did it behave? Future President Theodore Roosevelt personified a nation supremely confident that the 100 years ahead would be an American century. Over a decade that began in 1895 with the U.S. secretary of state declaring the United States “sovereign on this continent,” America liberated Cuba; threatened Britain and Germany with war to force them to accept American positions on disputes in Venezuela and Canada; backed an insurrection that split Colombia to create a new state of Panama (which immediately gave the U.S. concessions to build the Panama Canal); and attempted to overthrow the government of Mexico, which was supported by the United Kingdom and financed by London bankers. In the half century that followed, U.S. military forces intervened in “our hemisphere” on more than 30 separate occasions to settle economic or territorial disputes in terms favorable to Americans, or oust leaders they judged unacceptable.

Theodore Roosevelt with U.S. troops at the Panama Canal Zone in 1906 (Wikimedia)

Theodore Roosevelt with U.S. troops at the Panama Canal Zone in 1906 (Wikimedia)

For example, in 1902, when British and German ships attempted to impose a naval blockade to force Venezuela to pay its debts to them, Roosevelt warned both countries that he would “be obliged to interfere by force if necessary” if they did not withdraw their ships. The British and Germans were persuaded to retreat and to resolve their dispute in terms satisfactory to the U.S. at The Hague. The following year, when Colombia refused to lease the Panama Canal Zone to the United States, America sponsored Panamanian secessionists, recognized the new Panamanian government within hours of its declaration of independence, and sent the Marines to defend the new country. Roosevelt defended the U.S. intervention on the grounds that it was “justified in morals and therefore justified in law.” Shortly thereafter, Panama granted the United States rights to the Canal Zone “in perpetuity.”

* * *

When Deng Xiaoping initiated China’s fast march to the market in 1978, he announced a policy known as “hide and bide.” What China needed most abroad was stability and access to markets. The Chinese would thus “bide our time and hide our capabilities,” which Chinese military officers sometimes paraphrased as getting strong before getting even.

With the arrival of China’s new paramount leader, Xi Jinping, the era of “hide and bide” is over. Nearly three years into his 10-year term, Xi has stunned colleagues at home and China watchers abroad with the speed at which he has moved and the audacity of his ambitions. Domestically, he has bypassed rule by a seven-man standing committee and instead consolidated power in his own hands; ended flirtations with democratization by reasserting the Communist Party’s monopoly on political power; and attempted to transform China’s engine of growth from an export-focused economy to one driven by domestic consumption. Overseas, he has pursued a more active Chinese foreign policy that is increasingly assertive in advancing the country’s interests.

While the Western press is seized by the story line of “China’s economic slowdown,” few pause to note that China’s lower growth rate remains more than three times that of the United States. Many observers outside China have missed the great divergence between China’s economic performance and that of its competitors over the seven years since the financial crisis of 2008 and Great Recession. That shock caused virtually all other major economies to falter and decline. China never missed a year of growth, sustaining an average growth rate exceeding 8 percent. Indeed, since the financial crisis, nearly 40 percent of all growth in the global economy has occurred in just one country: China. The chart below illustrates China’s growth compared to growth among its peers in the BRICS group of emerging economies, advanced economies, and the world. From a common index of 100 in 2007, the divergence is dramatic.

GDP, 2007 — 2015

Harvard Belfer Center / IMF World Economic Outlook

Today, China has displaced the United States as the world’s largest economy measured in terms of the amount of goods and services a citizen can buy in his own country (purchasing power parity).

What Xi Jinping calls the “China Dream” expresses the deepest aspirations of hundreds of millions of Chinese, who wish to be not only rich but also powerful. At the core of China’s civilizational creed is the belief—or conceit—that China is the center of the universe. In the oft-repeated narrative, a century of Chinese weakness led to exploitation and national humiliation by Western colonialists and Japan. In Beijing’s view, China is now being restored to its rightful place, where its power commands recognition of and respect for China’s core interests.

A woodblock painting depicts the First Sino-Japanese War. (Toyohara Chikanobu / Wikimedia)

Last November, in a seminal meeting of the entire Chinese political and foreign-policy establishment, including the leadership of the People’s Liberation Army, Xi provided a comprehensive overview of his vision of China’s role in the world. The display of self-confidence bordered on hubris. Xi began by offering an essentially Hegelian conception of the major historical trends toward multipolarity (i.e. not U.S. unipolarity) and the transformation of the international system (i.e. not the current U.S.-led system). In his words, a rejuvenated Chinese nation will build a “new type of international relations” through a “protracted” struggle over the nature of the international order. In the end, he assured his audience that “the growing trend toward a multipolar world will not change.”

Given objective trends, realists see an irresistible force approaching an immovable object. They ask which is less likely: China demanding a lesser role in the East and South China Seas than the United States did in the Caribbean or Atlantic in the early 20th century, or the U.S. sharing with China the predominance in the Western Pacific that America has enjoyed since World War II?

And yet in four of the 16 cases that the Belfer Center team analyzed, similar rivalries did not end in war. If leaders in the United States and China let structural factors drive these two great nations to war, they will not be able to hide behind a cloak of inevitability. Those who don’t learn from past successes and failures to find a better way forward will have no one to blame but themselves.

Actors dressed as Red Army soldiers mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, in Beijing. (Kim Kyung-Hoon / Reuters)

At this point, the established script for discussion of policy challenges calls for a pivot to a new strategy (or at least slogan), with a short to-do list that promises peaceful and prosperous relations with China. Shoehorning this challenge into that template would demonstrate only one thing: a failure to understand the central point I’m trying to make. What strategists need most at the moment is not a new strategy, but a long pause for reflection. If the tectonic shift caused by China’s rise poses a challenge of genuinely Thucydidean proportions, declarations about “rebalancing,” or revitalizing “engage and hedge,” or presidential hopefuls’ calls for more “muscular” or “robust” variants of the same, amount to little more than aspirin treating cancer. Future historians will compare such assertions to the reveries of British, German, and Russian leaders as they sleepwalked into 1914.

The rise of a 5,000-year-old civilization with 1.3 billion people is not a problem to be fixed. It is a condition—a chronic condition that will have to be managed over a generation. Success will require not just a new slogan, more frequent summits of presidents, and additional meetings of departmental working groups. Managing this relationship without war will demand sustained attention, week by week, at the highest level in both countries. It will entail a depth of mutual understanding not seen since the Henry Kissinger–Zhou Enlai conversations in the 1970s. Most significantly, it will mean more radical changes in attitudes and actions, by leaders and publics alike, than anyone has yet imagined.