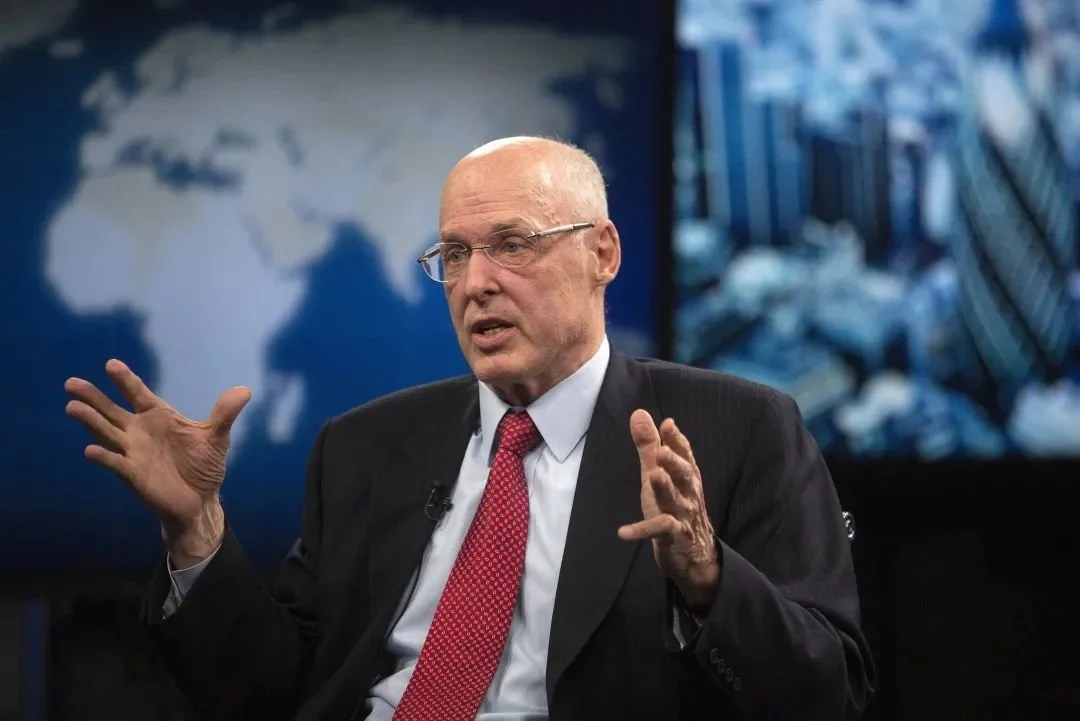

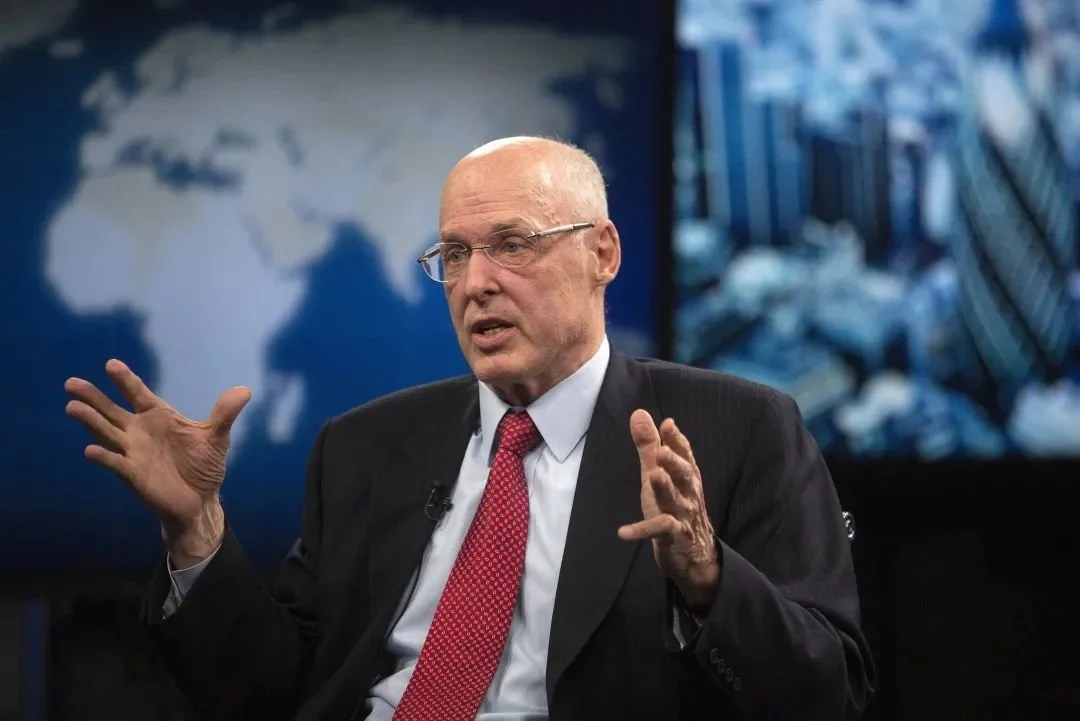

1946年3月28日生人,曾担任投资银行高盛集团的主席和行政总监。2006年至2009年担任美国财政部长。2006年5月30日,美国总统布什提名为财政部长以接替约翰·威廉·史诺。[1]6月28日,美国参议院确认他的提名。[2]7月10日,保尔森在仪式中宣誓就任。任期于2009年1月20日届满。

导 语

在2月初美国国务卿布林肯访华之际,美国前财政部长、保尔森基金会主席亨利·保尔森(Henry M. Paulson)1月26日在美国《外交事务》杂志网站发表题为《美国对华政策并不奏效——广泛脱钩危险所在》(America's China Policy Is Not Working-The Dangers of a Broad Decoupling)的文章,呼吁美中两国决策者更频繁会面、更坦诚地沟通。他认为,美国当前对华政策对美国自己的伤害更大,美国联合盟友制衡中国的策略并不奏效,与中国开展经济合作符合华盛顿的利益。

他提醒到,“以美国自身利益为代价惩罚中国”的政治意愿正在美国国会推波助澜。拜登政府需要拿出勇气,“明智且果敢”地应对这些挑战。以下是保尔森此文主要内容:

尽管人们都在谈论我们如何进入了一个新的全球化时代,但刚刚过去的一年却与2008年惊人的相似。那一年,俄罗斯入侵了它的邻国格鲁吉亚,美国与伊朗、朝鲜关系持续紧张,全球经济也面临严峻挑战。然而,一个显著的区别是如今的中美关系。2008年,即使中美之间存在政治和意识形态的分歧、有安全利益的冲突以及双方对全球经济,包括对人民币币值和中国工业补贴政策,存在不同意见,中美还是能够开展符合自身利益的合作。

作为财政部长,我在2008年金融危机期间与中国领导人合作,防止危机蔓延,减缓危机带来的最坏影响,恢复宏观经济的稳定。如今,这样的合作变得不可思议。与2008年金融危机时期不同的是,新冠疫情并没有促进中美间的合作,而是加深了双方的对立。

▲亨利·保尔森(Henry M. Paulson), 他曾在小布什总统政府担任美国第74任财政部长,任期从2006年7月至2009年1月。

世界显然已经改变。如今的中国领导层更坚定自信。2008年以来,中国的经济规模增长了两倍多。尽管中国经济对外部竞争开放的程度,不及许多西方国家的预期,美国对中国的态度急剧转向负面,但一个不变的事实是:如果没有稳定的美中关系来保证两国在共同利益上的合作,世界将变得危险和不那么繁荣。

与2008年不同的是,2023年的中美关系在几乎所有方面都将出现变化。双方都从国家安全的角度看待双边关系,甚至对过去被视为积极的双边事务也是如此,例如创造就业的投资或突破性技术的协同创新。中方将美国旨在保护美国技术的出口管制视为对中国未来发展的威胁;而美方认为,任何可能提升中国科技能力的举措,都将使中国作为一个战略竞争对手得以崛起,并帮助中国强化军事建设。

中美正在从一种彼此竞争但偶有合作的关系滑至几乎在所有方面都互相对抗的关系。结果,美国将自己的企业置于在盟友间的劣势地位,因为它限制了这些企业开展商业化创新的能力。这可能会让美国失去在其他国家的市场份额。对于那些担心美国会在与中国的竞争中失利的人来说,美方这样的行为可能会进一步确保这种担忧变成现实。

美国正试图与和自己拥有相近价值观的国家结盟,特别是亚洲和欧洲的“民主国家”,以此来制衡中国和向其施压。但这种策略并不奏效,它伤害了美国和中国,而且从长远来看,对美国人的伤害可能更甚。与中国在某些领域进行合作,并与世界第二大经济体保持有利的经济关系,显然也符合华盛顿的利益。

目前没有一个国家效仿美国的剧本来解决它们对中国的各种担忧。即使是美国最亲密的战略伙伴也不准备像美国那样,采取大规模性质的对抗、遏制举措。

事实上,许多国家正在做与华盛顿强硬派所寻求的相反的事情。许多国家并没有寻求在经济上和中国脱钩,而是继续深化与中国的贸易往来。也许这就是为什么在2020年中国取代美国成为欧盟最大的贸易伙伴。2022年,欧盟对中国的进出口贸易都有所增长。德国总统朔尔茨(Olaf Scholz)访华后,亚洲和欧洲领导人,都争相访问了中国,比如菲律宾总统小马科斯(Ferdinand Marcos, Jr)、法国总统马克龙(Emmanuel Macron)和意大利总理梅洛尼(Giorgia Meloni ),很有可能促成一种更广泛的态势。

华盛顿“更少中国”(less of China)的做法在“全球南方”国家的表现更糟。2021年中非贸易额达到历史新高,比2020年增长35%。美国大力推动华为等中国科技公司退出支柱型电信架构的行动在欧洲和印度收效相对较好,但在其他几乎所有地方都表现不佳。以沙特阿拉伯为例,它最大贸易伙伴就是中国,其2030年改革计划严重依赖与中国科技企业的合作,包括阿里巴巴和华为,即使在人工智能和云服务等美国瞄准的敏感领域也是如此;印尼是一个庞大的亚洲民主国家,华盛顿一直在拉拢印尼以抗衡中国的影响力。实际上,印尼已经将华为作为网络安全解决方案的首选合作伙伴,甚至是政府系统的首选合作伙伴。

随着疫情后中国重新开放,美国的这些努力更不可能成功。针对华盛顿的“更少中国”战略,中国也有自己的“更多的美国以外的所有国家”战略。中国已经调整其新冠防疫政策,重新开放边境,吸引外国资本和投资,以重启经济。随着中国开启新一年的外交布局,围绕投资、基建和贸易做出新的承诺,美国终究会发现,受挫的原来是自己,而非中国。

贸易规则就是一个很好的例子。2017年,时任美国总统特朗普退出了跨太平洋伙伴关系协定(TPP),6年后,华盛顿显然无意重新加入TPP。然而,中国已经申请加入该协议,该协议现在被称为《全面与进步跨太平洋伙伴关系协定》(CPTPP)。中国还批准了《亚洲区域全面经济伙伴关系协定》(RCEP),申请加入《数字经济伙伴关系协定》(DEPA),并与厄瓜多尔、新西兰等国升级或启动了新的自贸协定。中国现在是世界上最大的贸易国。近三分之二的国家与中国的贸易额超过了与美国的贸易额。

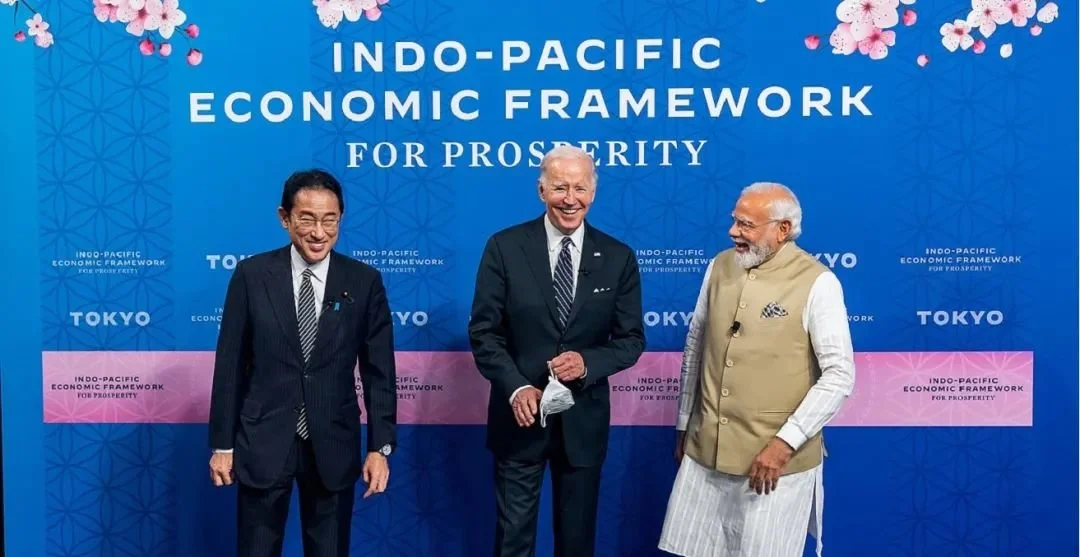

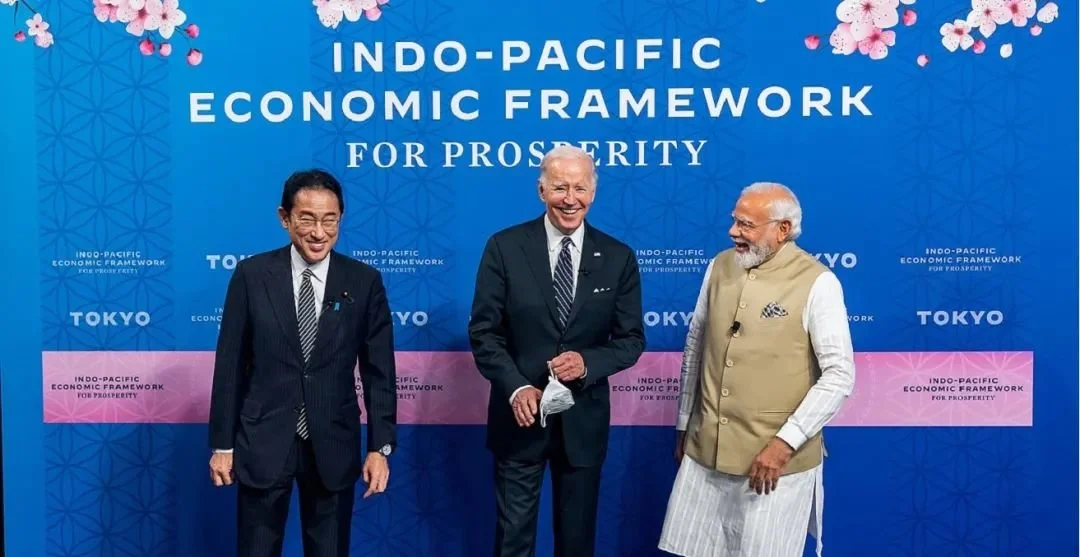

与此同时,美国当前坚持的以“工人利益为中心”的贸易政策,看上去就和贸易保护主义无异。相比之下,华盛顿印太经济框架(IPEF)的制定也有些畏首畏尾。该框架的推进困难,尤其是因为它拒绝给予加入该框架的国家新的市场准入。

华盛顿面临着与经济引力背道而驰的风险。美国已经成功控制了最敏感的技术,包括先进的半导体。但如果美国的战略是基于促使与中国在技术领域更广泛的分离,反而不易成功,因为大多数国家都没有追随美国,并且最终可能会找到调整的方法。

▲2022年5月23日,日本东京,日本首相岸田文雄、美国总统拜登、印度总理莫迪在东京都六本木的泉花园画廊举行“印太经济框架”(简称IPEF)启动仪式。

这些将中国拒之门外的努力当然会伤害中国,但也会伤害美国,伤害那些依赖中国供应商的“美国就业创造者”企业,包括普通的美国企业。这些企业几乎没有变通办法,在高通胀和高额能源账单的重压之下,很容易被压垮。美国企业被置于巨大的竞争劣势,最终买单的还是美国消费者。纠正这一问题的一个明智做法就是取消对中国商品加征的关税,这些关税只会导致消费品价格更高。这种加征关税的政策在政治上很受欢迎,但在经济上毫无意义。当然,美国也不应在没有得到回报的情况下取消这些关税。例如,华盛顿可以要求中国向更多美国商品开放市场。

归根结底,美国对华竞争始于国内。美中两国政治制度迥异。美国要想证明自己更胜一筹,就要坚持那些让美国经济成为全球羡慕的对象并且支撑美国国家安全的原则。美国还要在海外展现经济领导力。

至关重要的一点是,美国要赢得开发技术和吸引人才的竞赛,因为未来经济上的成功在很大程度上将由技术优势驱动。这就要求美国不仅要开发这些未来的技术,还要将它们商业化,而不是囤积它们。这要求美国制定全球标准,而不是将竞技场拱手让给中国。美国应该在贸易方面发挥领导作用,而不是退出有中国申请加入的贸易协定,切断美国企业的出口机会。中国不太可能对很多领域推行的政策很快做出调整。美国需要展现强硬,但要秉持公平,愿意对话,并且准备好与中国进行艰难且漫长的协作。

这种合作在过去是有意义的。2008年金融危机最严重的时候,中国是美国企业、银行和房利美(Fannie Mae)和房地美(Freddie Mac)最大的债权人。在中美战略经济对话期间,美国同中方领导人的密切协调帮助美国说服中国不要抛售美国国债,这对避免另一次大萧条至关重要。中国在2008年第一届G20峰会后推出的刺激计划也帮助抵消了金融危机的影响,并帮助全球经济复苏。

金融危机是不可避免的,如果中美这两个最大的经济体和经济增长引擎能够通过沟通和协调来预测和预防经济崩溃,并消减其影响,那么以限制两国和世界经济困境的方式来管理金融危机将容易得多。这样做符合中美两国的共同利益。但这需要美国财政部长耶伦(Janet Yellen)及其同事与中国同行定期举行对话,讨论并监测全球和国内的宏观经济和金融风险。

实体经济的冲击会迅速波及金融体系,如果不加以解决,过度金融会对人们的生活造成严重破坏。在现代金融中,金钱可以以光速在世界各地流动,这使得世界看起来越来越小。中国经济规模如此之大,并且融入了全球,若有震荡必然立即波及全球金融市场。当然,中美之间的一级和二级经济和金融联系如此广泛和深入,它们是不可能消失的,这使得两国就宏观经济风险交换看法变得尤为重要。

中国是美国国债的第二大持有者,也是其他美国证券的主要投资者,因此中国了解美国的经济政策并对美国政策制定者抱有信心符合两国的利益,尤其是在美国国会为债务上限争吵不休的时候。美国政策制定者也要更好地了解中国的经济政策和挑战,对这中美两国都至关重要。

美国需要巩固拜登政府试图阻止两国关系自由落体的努力,这样做至关重要,因为美国争取到用来施压中国的各个盟友和伙伴都希望在可能的情况下和中国开展合作。这也是拜登寻求同中国建立双边关系“护栏”的其中一个原因。

为了加强协调,中美两国的决策者应该更频繁地会面,更坦诚地交谈。友好关系不是这种合作的先决条件。两国在政治、安全和意识形态领域的明显紧张关系并不阻止彼此在宏观经济稳定、流行病防范、气候变化、打击恐怖主义、核不扩散以及为全球金融体系设置防火墙以抵御未来金融危机等问题上进行利己的合作。美国国务卿布林肯(Antony Blinken)即将访华是一个很好的起点。耶伦应该定期与中方接触。美联储主席鲍威尔也应该与中国央行行长进行对话。美国必须控制武器相关技术以及两用和多用途技术,并更严格地审查相关投资和并购,但美国不需要在对国家安全或世界民主国家在技术前沿的竞争力不重要的领域推动和中国的分离。

某种程度的脱钩是不可避免的。在高科技领域,一些有针对性的脱钩是绝对有必要的。但全方位脱钩毫无意义。美国人受益于融入世界,中国仍将是一个巨大的市场,美国人可以参与其中,也可以将其让给美国的竞争对手。中国是世界第二大经济体、最大的制造国和最大的贸易国。未来几十年,中国将是全球金融格局的重要组成部分。美国不该宿命论地接受经济铁幕的落下,而应积极与中国谈判,为美国人在中国市场上赢得机会。美国官员应该与中国领导层认真讨论,如何以一种互惠贸易的方式处理脱钩问题。目前,两国主要是相互指控和反诉,而没有采取任何措施扩大经济互惠互利的机会。

美中两国的安全紧张局势不可能凭空消失。尤其是在俄罗斯入侵乌克兰之后,美国人有理由担心中国会到处施展影响力。美国加强威慑和改善同盟友的关系都是答案的重要组成部分。但美国的盟友和伙伴毫不掩饰第展现了他们“不孤立或遏制”中国的意愿。这是华盛顿应该得到的一个信息,即世界拒绝与中国脱离关系。

美国国内政治风向强劲。“以美国自身利益为代价惩罚中国”的政治意愿正在美国国会推波助澜。拜登政府需要拿出勇气,“明智且果敢”地应对这些挑战。

America's China Policy Is Not Working

The Dangers of a Broad Decoupling

By Henry M. Paulson, Jr. January 26, 2023

U.S. President Joe Biden with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Bali, Indonesia, November 2022

For all the talk of how we have entered a new global era, the last year bears a striking resemblance to 2008. That year, Russia invaded its neighbor, Georgia. Tensions with Iran and North Korea were perennially high. And the world faced severe global economic challenges.

One notable difference, however, is the state of Chinese-U.S. relations. At that time, self-interested cooperation was possible even amid political and ideological differences, clashing security interests, and divergent views about the global economy, including China’s currency valuation and its industrial subsidies. As Treasury secretary, I worked with Chinese leaders during the 2008 financial crisis to forestall contagion, mitigate the worst effects of the crisis, and restore macroeconomic stability.

Today, such cooperation is inconceivable. Unlike during the financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic failed to spark Chinese-U.S. cooperation and only intensified deepening antagonism. China and the United States jab accusatory fingers at each other, blame each other for bad policies, and trade barbs about a global economic downturn from which both countries and the world have yet to recover.

The world has clearly changed. China has very different and more assertive leadership. It has more than tripled the size of its economy since 2008 and now has stronger capabilities to pursue adversarial policies. At the same time, it has done far less to open its economy to foreign competition than many in the West have advocated and expected. Meanwhile, U.S. attitudes toward China have turned sharply negative, as have the politics in Washington. What has not changed, however, is the fact that without a stable relationship between the United States and China, where cooperation on shared interests is possible, the world will be a very dangerous and less prosperous place.

In 2023, unlike 2008, nearly every aspect of Chinese-U.S. relations is viewed by both sides through the prism of national security, even matters that were once regarded as positive, such as job-creating investments or co-innovation in breakthrough technologies. Beijing regards U.S. export controls aimed at protecting the United States’ technologies as a threat to China’s future growth; Washington views anything that could advance China’s technological capability as enabling the rise of a strategic competitor and aiding Beijing’s aggressive military buildup.

China and the United States are in a headlong descent from a competitive but sometimes cooperative relationship to one that is confrontational in nearly every respect. As a result, the United States faces the prospect of putting its companies at a disadvantage relative to its allies, limiting its ability to commercialize innovations. It could lose market share in third countries. For those who fear the United States is losing the competitive race with China, U.S. actions threaten to ensure that fear is realized.

COALITION OF THE WILLING

The United States is attempting to organize a coalition of like-minded countries, especially the democracies of Asia and Europe, to counterbalance and pressure China. But this strategy is not working; it hurts the United States as well as China; and over the long term, is likely to hurt Americans more than Chinese people. It is also clearly in Washington’s interest to cooperate or work in complementary ways with China in certain areas and to maintain a beneficial economic relationship with the world’s second-largest economy.

Although many countries share Washington’s antipathy to China’s policies, practices, and conduct, no country is emulating Washington’s playbook for addressing these concerns. It is true that nearly every major U.S. partner is tightening up its export controls on sensitive technologies, scrutinizing and often blocking Chinese investments, and calling out Beijing’s coercive economic policies and military pressure. But even Washington’s closest strategic partners are not prepared to confront, attempt to contain, or economically deintegrate China as broadly as the United States is.

In fact, many countries are doing the opposite of what the hardest-line voices in Washington seek. Instead of decoupling or deintegrating economically, many countries are instead deepening trade with China even as they hedge against potential Chinese pressure by diversifying business operations, building new supply chains in third countries, and reducing exposure in the most sensitive areas. Perhaps that is why, in 2020, despite years of American warnings, China overtook the United States as the European Union’s largest trading partner. Both EU exports to and imports from China grew in 2022. And Asian and European leaders, spurred by the November 2022 visit to Beijing by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, now look set to beat a path to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s door, with trips by Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., French President Emmanuel Macron, and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni likely to drive a broader trend.

Washington risks pushing against economic gravity.

Washington’s “less of China” approach is faring even worse in the global South. Chinese-African trade reached a historic high in 2021, rising by 35 percent from 2020. An intensive U.S. campaign to push Chinese technology firms like Huawei out of backbone telecommunications architecture has fared comparatively well in Europe and India but poorly nearly everywhere else. Just take Saudi Arabia. Its largest trading partner is China, and its Vision 2030 reform plan leans heavily on hoped-for collaboration with Chinese tech firms, including Alibaba and Huawei, even in the sensitive areas that are squarely in Washington’s crosshairs, such as artificial intelligence and cloud services. Indonesia, a huge Asian democracy that Washington has courted to counterbalance Chinese influence, has actually made Huawei its partner of choice for cybersecurity solutions, and even for government systems.

These U.S. efforts are likely to be even less successful now that China is reopening. Beijing is matching Washington’s “less of China” strategy with its own “more of everyone but America” strategy.

Beijing is reversing its restrictive COVID-19 policies, reopening its borders, courting foreign leaders, and seeking foreign capital and investment to reboot its economy. Last year, Xi made his first foreign trips since the outbreak of the pandemic to Central Asia and the Middle East, underlining his strategy to increase China’s global connectivity. With Xi now traveling the world again after a three-year hiatus, scattering renewed pledges of Chinese investment, infrastructure, and trade at every stop, it is Washington, not Beijing, that may soon find itself frustrated.

Trade rules are a good example. In 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and six years later, Washington clearly has no intention of rejoining it. Yet Beijing has applied to join the pact, now called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). China has also ratified the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in Asia, applied to join the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement, and upgraded or initiated new free trade agreements with countries from Ecuador to New Zealand. China is now the world’s largest trading nation. Nearly two-thirds of all countries trade more with China than with the United States.

Competition with China begins at home.

Meanwhile, the United States is pursuing a “worker-centric” trade policy that looks very much like protectionism. And Washington’s Indo-Pacific Economic Framework looks timid by comparison. The framework is struggling, not least because it denies new market access to the very countries that have joined the pacts that Washington has shunned.

Washington risks pushing against economic gravity. The United States has succeeded in controlling the most sensitive technologies, including advanced semiconductors. But it will have less success with a strategy premised on promoting broader technology deintegration with China because most countries are not following its lead and may, eventually, find ways to adjust.

These efforts to shut out China will certainly hurt China, but they hurt the United States, too. American businesses are put at a huge competitive disadvantage, and U.S. consumers pay the price. One sensible step to correct this problem would be to limit tariffs on imports of Chinese consumer goods, which make them more expensive for U.S. consumers. These are politically popular but economically nonsensical. They hurt China but hurt U.S. job creators, as well, including ordinary companies that depend on Chinese suppliers, have few workarounds, and have been crushed under the weight of inflation and high energy bills. But these should not be lifted without getting something in return. For example, Washington should push China to live up to the terms of the 2020 Phase One trade agreement, including by buying more U.S. agricultural products. China also should be required to open its markets to more U.S. goods.

TALK IT OUT

Ultimately, competition with China begins at home. The United States and China have very different political systems. The United States’ is superior, but it must be demonstrated through results. This means sticking to the principles that made the U.S. economy the envy of the world and underpin U.S. national security. It also means demonstrating economic leadership abroad.

It is critically important that Washington win the race to develop technologies and attract talent. Economic success will be driven to a large extent by technological superiority. This requires the United States not just to develop those technologies of the future but to commercialize them and not hoard them. It demands the United States set global standards rather than ceding the playing field to China. And the United States should be leading on trade, not withdrawing from the very pacts China has applied to join and cutting U.S. workers off from export opportunities.

To be sure, security tensions are baked into the relationship, and Xi’s China is a formidable competitor with which the United States must take a very tough-minded approach. Beijing is pursuing policies inimical to U.S. interests in many areas, and it is unlikely to adjust anytime soon. Washington needs to be tough-minded but fair, open to dialogue but not for its own sake, and prepared for a tough, long slog in pursuing self-interested coordination with China.

Such cooperation has been meaningful in the past. At the height of the financial crisis of 2008, China was a huge holder of corporate, banking, and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac securities. The close coordination established with Chinese leaders during the Strategic Economic Dialogue helped Washington convince Beijing not to sell U.S. securities, which was critical to avoiding another Great Depression. The Chinese stimulus package that followed the first G-20 in 2008 also helped to counteract the effects of the crisis and assist the global economic recovery.

Xi's China is a formidable competitor.

Financial crises are inevitable, and they will be much easier to manage in ways that limit the economic hardship in both countries and the world if the two largest economies and drivers of economic growth are able to communicate and coordinate to anticipate and forestall economic disruption, as well as to mitigate its impact. And it is in China and the United States’ shared interests to do just that. But this requires U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and her colleagues to have a regular dialogue with their Chinese counterparts where they discuss and monitor global and domestic macroeconomic and financial risks.

A shock in the real economy can move quickly to the financial system, and financial excesses can wreak havoc on people’s lives if left unaddressed. Modern finance, where money can move around the world with the speed of light, makes the world seem like an increasingly small place. The Chinese economy is so large and integrated globally that disruptions there in 2015 and 2021 immediately rippled through global financial markets. And, of course, the primary and secondary economic and financial linkages between China and the United States are so broad and deep they cannot be wished away, which makes it particularly important that the two states share views on macroeconomic risks. China is the second-largest holder of U.S. Treasury bonds and a large investor in other U.S. securities, so it is in both countries’ interests for China to have an understanding of U.S. economic policy and confidence in U.S. policymakers, particularly when Congress is wrangling over the debt limit. The lack of transparency around China’s lending to some very troubled economies and the large amount of U.S. business investment in the Chinese economy, which can seem like a black box to outside analysts and where abrupt policy changes can take the market by surprise, mean it is critical to both states that U.S. policymakers have a better understanding of China’s economic policies and challenges.

The United States needs to solidify the floor that the Biden administration has tried to put under the freefall. This is essential because the allies and partners Washington hopes to enlist to pressure China expect a good-faith effort to seek cooperation with it, where possible. And that is one reason that U.S. President Joe Biden, in his meeting with Xi in Indonesia last November, sought to establish guardrails around a deteriorating relationship.

To improve coordination, Chinese and U.S. decision-makers should meet more frequently and talk much more candidly. Friendship is no prerequisite for such coordination. And obvious political, security, and ideological tensions do not preclude self-interested cooperation on issues such as macroeconomic stability, pandemic preparedness, climate change, combating terrorism, nuclear nonproliferation, and firewalling the global financial system against future crisis and contagion. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s upcoming meeting with Chinese State Councilor Wang Yi is a good starting point. Yellen should be talking regularly to China’s new economic czar, He Lifeng. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell should also be speaking with China’s top central banker.

Washington should negotiate aggressively with Beijing to win opportunities for Americans in its market.

And Beijing should not hold hostage cooperation on global issues such as climate change because it is upset about unrelated issues. Linking different foreign policy issues undermines China’s effort to present itself as a constructive global problem solver.

The United States also needs to carefully distinguish what it must have from its allies from what is merely nice to have. Controlling weapons-related technologies and dual- and multiple-use technologies, and more intensively screening Chinese investments and mergers and acquisitions with global tech companies are a must. But Washington does not need to encourage deintegration in areas that are not central to national security or the competitiveness of the world’s democracies at the technological bleeding edge.

Some level of decoupling is inevitable. In the case of high technologies, some targeted decoupling will be absolutely necessary. But wholesale decoupling makes no sense. Americans benefit from access to the world, and China will remain a huge market that Americans can either partake in or abandon to competitors. China is the world’s second-largest economy, its largest manufacturer, and its largest trader. It will be a big part of the global financial picture for decades to come. Instead of fatalistically accepting the descent of an economic iron curtain, Washington should negotiate aggressively with China to win opportunities for Americans in its market. Administration officials should have serious discussions with Chinese leadership about how to manage the decoupling in a way that allows for mutually beneficial trade. Right now, the two countries are mostly trading charges and countercharges while doing nothing to expand mutually beneficial economic opportunities.

Chinese-U.S. security tensions cannot be wished away, and Americans are rightly concerned, especially after the brutal Russian invasion of Ukraine, that Beijing will throw its weight around, not least by coercing Taiwan. Bolstering deterrence is a big part of the answer. So are improved relations with allies. But U.S. allies and partners have made no secret of their desire not to isolate or contain Beijing. That is one message Washington should take away from the world’s refusal to disengage with China—and from China’s effort to drive wedges between Washington and everyone else.

The political winds are strong and the desire to punish China even at the United States’ expense is driving many in Congress. Biden will need a lot of courage to be smart and bold in the face of these challenges.

Loading...

• Paywall-free reading of new articles and a century of archives

• Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

• Six issues a year in print, online, and audio editions

HENRY M. PAULSON, JR., is Founder and Chair of the Paulson Institute. He was Secretary of the U.S. Treasury from 2006 to 2009.

• More By Henry M. Paulson Jr.

More:

China Globalization Economics Business Finance Trade U.S. Foreign Policy Biden Administration Xi Jinping

Most-Read Articles

America’s China Policy Is Not Working

The Dangers of a Broad Decoupling

Henry M. Paulson, Jr.

Kennan’s Warning on Ukraine

Ambition, Insecurity, and the Perils of Independence

Frank Costigliola

Don’t Fear Putin’s Demise

Victory for Ukraine, Democracy for Russia

Garry Kasparov and Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Will Ukraine Wind Up Making Territorial Concessions to Russia?

Foreign Affairs Asks the Experts

Recommended Articles

How to Stop Chinese Coercion

The Case for Collective Resilience

Victor Cha

The World According to Xi Jinping

What China’s Ideologue in Chief Really Believes

Kevin Rudd