So what exactly is Labor’s China policy?

In opposition, Labor stood alongside the Coalition’s every move, only grumbling when the government descended into partisan point-scoring. Since coming to office, it has declared its desire to “stabilise” relations with China. It’s an ambiguous term, probably deliberately so, allowing different constituencies to each put their own spin on it. For Sino-Australian optimists, stabilisation will be seen as an improvement. China hawks interpret the term as consolidating a new normal of heightened tensions, with possibly a little less dog-whistling.

Is there any substance to the concept?

From Canberra’s point of view, the best-case scenario in Asia has always looked roughly the same: a world in which Australia directs an endless flow of exports to China from behind a wall of American steel. It was when that wall started showing signs of weakening that the Coalition led us on a deliberate turn towards talking up China as an enemy, in an effort to catalyse a more determined American-led containment effort.

The corollary here is that when America looks to be stepping up, Australia need not keep itself in the spotlight. Biden is doing enough now to signal a renewed American commitment to containing China. His most recent tranche of hi-tech export controls has convinced even skeptics that Washington is embarked on a policy of slowing China’s economic growth.

In this situation, Canberra may sense an opportunity to undo a little of the damage incurred while putting itself “out in front” (as Malcom Turnbull’s insiders termed his shift), and maybe also gain some wriggle room in case US efforts to stymie China’s rise fall flat.

If “stabilisation” has any meaning in policy terms, it is this.

The fact is, though, that the ALP remains committed to the whole suite of policies that got us here in the first place. While the Australian media now anxiously anticipates signs of repair to the diplomatic rift, only a few weeks ago headlines were hailing the arrival of B-52s in the Northern Territory. Whether or not the submarines ever eventuate, Aukus has put us on a path towards ever-deepening military integration with the US, all aimed at China.

What is the point of calling for “stable” relations with a country while we openly arm ourselves for war against it?

A series of measures premised on the notion of China as a singularly hostile, dangerous country, remain in place: absurd restrictions on Chinese investment, visa bans on Chinese scholars of Australian studies, to name two examples. The accompanying rise in anti-Chinese racism has been well documented.

Rolling back some of this harmful legacy would give Australian diplomats a far better entry point to air their grievances with China than vague talk of “stabilisation”. Sadly, though, some China hawks have succeeded in framing any change to today’s policy settings as an intolerable concession to Beijing. That being the case, Albanese is likely to bring little concrete to the table in his meeting with Xi today.

I’m not the first to point out the perverse consequence of this kind of rhetoric: that our policies do end up being determined by China. Beijing’s opposition to a new Australian move all but ensures that we double down on it. It’s a habit of mind we need to get out of.

At a time of heightened interest in the cut-and-thrust of international diplomacy this may seem an odd thing to say, but we need to worry less about what China thinks, and more about the kind of country and society we want Australia to be. Australia’s militarised response to China is exacerbating global faultlines and fracturing our own society; it is, in a word, destabilising.

Yes, China is moving in a more authoritarian direction under Xi. But prolonged tensions between China and the west will see concerns with human rights jettisoned on both sides. The recent race to arm strongman Manasseh Sogavare’s Solomon Islands police gives us, in microcosm, a picture of what a future of regional rivalry looks like.

Opposing this vision of the future has nothing to do with pandering to Beijing. On the contrary, confronting Australia’s own contribution to current tensions is the only credible way to start a serious conversation with Beijing about its.

David Brophy

David Brophy is a senior lecturer in modern Chinese history at the University of Sydney and an author

China is far from alone in taking advantage of Australian universities’ self-inflicted wounds

Having long encouraged universities to find funding elsewhere, politicians now home in on their ties to China to argue that they’ve lost their way

Sanctions only escalate tensions. It's time to tackle the Uyghurs' plight differently

We have to make a credible case that western opposition to China’s policies is not geopolitical manoeuvring, says Australian academic David Brophy

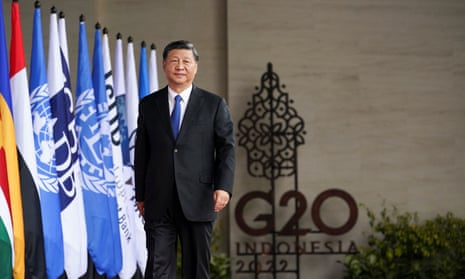

‘Australia’s militarised response to China is exacerbating global faultlines and fracturing our own society; it is, in a word, destabilising.’ Photograph: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

‘Australia’s militarised response to China is exacerbating global faultlines and fracturing our own society; it is, in a word, destabilising.’ Photograph: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters