笨狼发牢骚

发发牢骚,解解闷,消消愁大家也许不太留意黑岩(BlackRock,黑岩自己起的中外名字是贝莱德,够响)是个什么样的公司,不过不知道交易所板块交易金(ETF)的估计不多。板块金不但方便,也给传统的给共存基金了个致命的冲,难说它还能撑多少年。而在板块金的行业,大名鼎鼎,压倒性的是I版,既iShares,而I版就是黑岩的杰作。

黑岩I版工具,罗列表

黑岩是世界上最大的理财公司,管辖4.5万亿(美元)的资产,即使你不用I版,难免不予黑岩有瓜葛,故此其对世界经济的态度也是大家关注的的项目。本来黑岩管理完善,理财有方,除了帮大家理财。,自己也常常赚的大满贯。只是时日不再,风光难持,除了跟着党大步走,其他法子大都不灵,只是这种瞎着眼睛不看路的招子向来不是黑岩此类理财专业店的手段,这一来,黑岩也陷入了困境。

近日,黑岩公布收成(上市排号BLK.N),不光鲜。

《路透社》BlackRock to restructure after 'tough' first quarter

《华尔街日报》BlackRock Gains $36 Billion in New Client Funds, But Misses Earnings Expectations

黑岩的老总叫芬克(Larry Fint),公开说话不多,但有份量。他说“此季度难过”。在给股东的公开信里他说:

《华尔街日报网文》BlackRock’s Larry Fink Strikes Pessimistic Tone on Global Economy in Letter

对日本的政策忧虑尤甚:

The world's largest investor says negative rates are breeding a disaster for the economy

芬克掌握的资料多,见世面广,能对中期的世界经济有一个叫合理的判断,对我做全局判断有影响。二月间当股市大跌到近1800是,他觉得股市还有可能再跌10%,原因是“市场毫无惊恐的感觉”,这在当时属于少数观点。我倒不是就信了他的,但对市场无动于衷还是有同感。

公司收成后,芬克出头说了话。

《商业有线电视CNBC》采访

This is 'biggest crisis' in the world

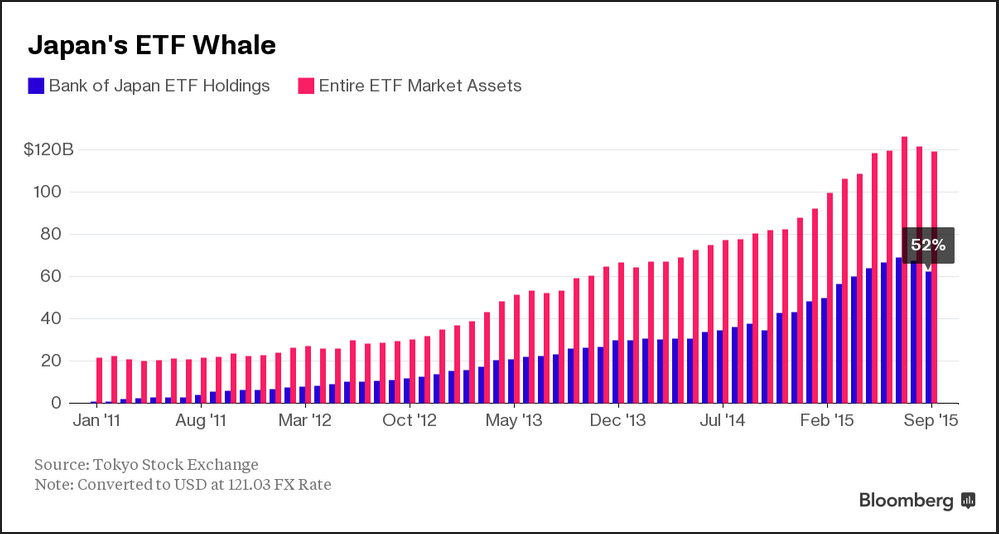

大家对各国央行励志救市的行径都是心照不宣,觉得能发财,不宜多说闲话,参见我的姚奶奶当家。不过瞪着大眼睛的人不少,等着啥时跳车逃离。举个例子,世界上没有比日本央行更加赤裸裸的投入股市的,中国与其一比,简直就是小儿科。半年前,日央行就已经拥有过半的板金了:

《彭博》Owning Half of Japan's ETF Market Might Not Be Enough for Kuroda

黑田东彥还觉得不够。够意思。在债券市场,那就是央行的本份了:

昨天,黑田东彥要来真的:

《路透社》BOJ warming to idea of buying more stocks funds: sources

公开出头叫嚷央行政策危害的还有埃里安(Mohamed El-Erian,曾任太平洋投资管理公司(PIMCO)擔任首席執行官兼联合首席投资官老总),埃里安觉得现在央行基本是回天乏術,到了黔驴技穷之际,接着采用目前的支持,只能给世界经济带来巨大的危害。

《彭博》Japan Is Fast Approaching the Quantitative Limits of Quantitative Easing

实际上央行此种行径无异承认第一其货币政策是彻底失败,行不通,只不过经济学家不这么说,之说还不够,加码下次准行,标准爱因斯坦所说的“疯了”;第二全球(各国政府的)财政政策也基本失败。只有在财政政策失败的情形下,央行才被迫用此下策。

没人说,也没人相信你这么觉得股市明天就塌了。只是爬得高跌的惨,靠吹上去的,迟早的事儿。反正是过了这村就没了这店,能吃上好饭,大家不会放过,不过酒醒了,还得盯着自己的钱包啊。

【附录】

《华尔街日报》Japan’s Negative-Rate Experiment Is Floundering

Trading withers in money markets, yen goes on a tear; ‘every day is like being Alice in Wonderland’

TOKYO—Japan’s two-month experiment with negative interest rates is producing some unexpected results.

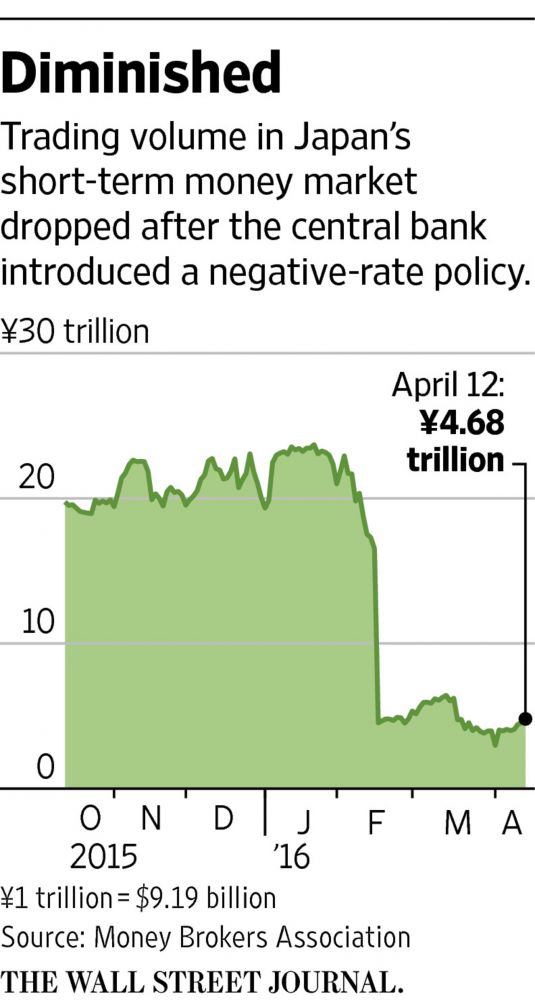

Trading has withered in Japan’s money markets, where big banks and others usually park their excess cash hoping to receive some interest—despite predictions from the Bank of Japan that its latest easing of monetary policy would spark more activity. And there has been a rush in demand for Japanese government bonds even as many yields went below zero.

Instead of falling, the yen has surged to 18-month highs against the U.S. dollar.

Still, Japan’s central-bank governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, who was in New York Wednesday, said the Bank of Japan is ready to expand its bond-buying program and cut interest rates further into negative territory as it attempts to bolster economic growth. The BOJ “will not hesitate to take additional easing measures in terms of…quantity, quality and the interest rate if it is judged necessary,” he said.

Participants in the Japanese markets have less conviction than Mr. Kuroda. In interviews, they describe a banking and finance system that is increasingly scrambled by negative rates and their consequences.

“Every day is like being Alice in Wonderland,” said Tomohisa Fujiki, head of interest-rate strategy at BNP Paribas Securities Japan. “Interest-rate levels are having little effect on credit demand, the market function is declining. You can’t expect everything to go according to plan.”

Japan surprised markets in January when it set a minus—0.1% rate on some deposits that banks place at the central bank, effective from mid-February. Its move was designed to encourage banks to lend more, spurring higher spending and inflation. Yet that has not been the case so far.

Lower interest rates normally lead a country’s currency to depreciate, helping its exporters—a key aim of “Abenomics,” the package of stimulus measures brought in by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

《华尔街日报》相关报道

A World of Negative Rates

As central bankers around the world push deeper into the once-unthinkable world of negative interest rates—essentially charging customers to hold their cash—The Wall Street Journal explores how negative rates are playing out on the ground and what they mean for policy makers and markets. Other articles in the series:

A Swiss Bank Enters Uncharted Territory

German Life Insurers Feel Pain of Low Rates

Duration Risk: The Bomb Ticking Inside Today’s Bond Market

In Denmark, Home Borrowers Collect Interest

Streetwise: The Next Step: A ‘Helicopter Drop’

Would Negative Rates Work in the U.S.?

Negative Rates: What You Need to Know

Read on Flipboard: A World Awash in Negative Rates

Instead, the yen has been bolstered both by its re-emergence this year as a haven currency amid uncertain global markets, and by the dollar’s recent weakness after the Federal Reserve pared back expectations of U.S. interest-rate increases.

Demand is coming from an unusual source: foreign investors, who in the past have largely stayed out of the low-yield market but have recently jumped in because of rising returns on Japanese-bond trades thanks to the cheaply funded yen.

Traders also have pushed up the yen believing Japan’s central bank can’t do much more to ease policy.

“There is no guarantee that lowering interest rates encourages corporate capital expenditures or expedites the shift of household financial assets from savings to investment,” said Nobuyuki Hirano, president of Mitsubishi UFJ Financial?Group?Inc., Japan’s biggest bank, on Thursday, adding the negative-interest policy had caused households and businesses to rein in spending amid growing uncertainty over the future.

One problem has been Japanese banks’ computer systems: The trade-confirmation system used by money-market brokers wasn’t fully updated for negative interest rates until over a month after the BOJ rate cut. Money-market trading volumes dropped to their lowest level since at least 2011 at the end of March, according to Japan’s Money Brokers Association, down to nearly a 10th of January’s levels.

Money markets allow banks and other financial institutions to lend and borrow money for a period of less than a year, often not backed by collateral. If fewer banks invest cash in short-term markets, it is harder for other banks to get short-term loans to finance their operations.

Japanese trust banks that manage cash on behalf of mutual and pension funds have in recent weeks been placing excess money on deposit at the BOJ rather than into overnight money markets, where it might now attract a negative interest rate.

“If the money market dries up, if there is an event like the Lehman crisis, there won’t be the infrastructure for banks to raise capital,” said Naomi Muguruma, strategist at Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities. “It could cause interest rates to rise sharply.”

Placing money at the central bank also can attract a negative-interest-rate charge, if the amount of cash set aside in this way exceeds the trust bank’s quota. Starting on April 18, Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Banking Corp. will start passing on that charge to mutual-fund managers and pension funds, levying a 0.1% and 0.06% fee respectively on excess cash that it used to invest in the money market. Another large institution, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank Ltd., says it will implement similar fees.

Problems in the money markets have run counter to Mr. Kuroda’s expectations: last month he said that as market players get used to negative rates, money-market trading should increase. Mr. Kuroda predicted banks that had to pay a minus-0.1% interest rate on some of their reserves would want to lend out that money for a higher rate.

Instead, Japanese financial institutions have been searching overseas for higher returns, without a corresponding rise in investment at home. Japanese investors bought a total of ¥5.47 trillion ($50 billion) worth of foreign securities in March, up 11% from February, according to the finance ministry.

In turn, the amount foreign financial institutions can charge to lend greenbacks to Japanese investors has surged. The premium for a three-month contract to exchange yen for dollars is now at ¥0.298, almost twice what it was a year ago.

Foreign investors have been recycling the yen they get back into Japanese government bonds, traders say, even though yields on a range of these bonds have turned negative in recent weeks—meaning investors who buy them end up paying money to Japan’s government. But the fee foreign institutions can charge to lend dollars is now so high that it outweighs the cost of holding negative-yield-bearing bonds, which remain the safest place for investors to park their yen.

The upshot: an unusual bout of foreign interest in Japan’s government bonds, an often sleepy market where overseas investors have generally held under 10% of outstanding bonds. Net foreign buying of medium-term Japanese government bonds was double the 12-month average in February, the most recent month for which data are available.

In all, foreigners bought a net ¥18.3 trillion worth of Japanese government bonds in February, according to the Japan Securities Dealers Association, up 16% from the month before. Overseas investors accounted for over one-quarter of all trading in short-term Japanese government bonds that month, and 15% of trading in medium-term bonds.

The strong desire among some Japanese investors for dollars hasn’t been enough to keep the yen down, however.

“There’s no rhyme or reason on why the yen would strengthen when interest rates are negative,” said Bart Wakabayashi, managing director at State Street Global Markets. “But the yen has now reasserted itself as a safe-haven currency on concerns about China and the global economy. And at the same time, doubts are emerging over the staying power of Abenomics.”