风萧萧_Frank

以文会友日本打工人敬业度指数全球倒数,这是为何?

言若 译言 2023-09-27 山西

员工对工作充满热情,积极主动参与和投入到工作中,积极主动帮公司取得成功,这种敬业的精神在日本似乎已变得死气沉沉。美国调研机构过去十多年的持续调查研究显示:日本的员工敬业度已经远远落后于全球平均水平。

毕业于耶鲁大学的罗谢尔·科普(Rochelle Kopp)是一位管理顾问,不仅与硅谷很多跨国企业合作,还与在全球展开业务的多家日本企业有密切合作,同时也是日本跨文化咨询公司的创始人。

在罗谢尔看来,日本员工敬业度低并不是什么奇怪的事,因为在过去的几年里,她遇到越来越多的日本人,不管是从企业高管,还是报纸编辑,抑或学者,都告诉她同样的事情:日本人“不再有梦想”。

01 敬业水平落后

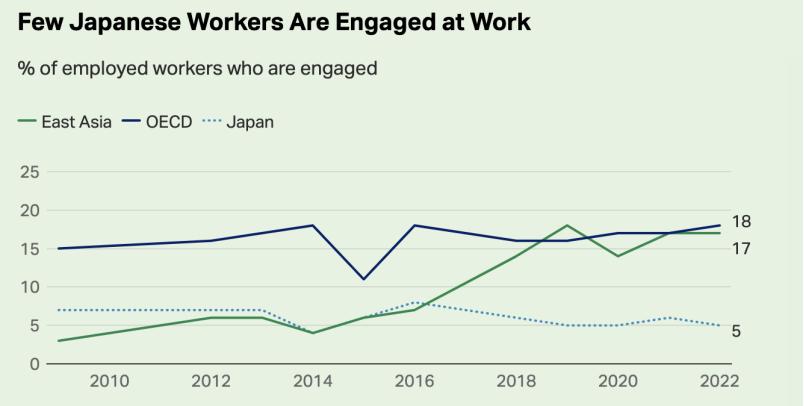

根据美国调研公司盖洛普(Gallup)本月发布的最新研究报告,日本人是世界上敬业度最低的劳动力之一,2022年,日本的员工敬业度只有5%,与23%的全球平均水平形成鲜明对比,日本人对工作的热情和投入远低于全球平均水平。

日本这种低热情和低投入并不是新冒出来的情况,而是长期的态势。报告指出,自2009年以来,日本人对工作的敬业程度持续低于全球水平,维持在4%到8%之间。

与其他高收入经济体以及地理和文化上一致的邻国相比,日本的敬业表现也越加落后。

比如,日本是经济合作与发展组织(OECD)中一员,OECD成员国(共37个国家)的平均员工敬业程度为18%,而日本却仅为这个平均水平的三分之一,而且日本与OECD平均水平不断扩大。2009年,日本人对工作的敬业度与OECD平均水平相差8个百分点,到了2022年,扩大到了13个百分点。

分析认为,员工敬业度如果低,那么虽然员工在工作中投入了时间,却不愿投入精力和热情,他们的努力和付出非常少、效率非常低,这些人通常比敬业者更易感到压力和怠倦。

报告称,在日本,73%的员工属于这种情况,高于全球平均水平(59%)。 作为发达国家之一、曾被冠名“工匠”精神的日本,为何却成了世界上员工敬业度最低的国家之一?

02 兴趣缺失

2020年,日本经济产业省出台文件强调需要提高日本的员工敬业度,而日本的很多企业也意识到员工敬业度的重要性,将“敬业度”的概念引入到人力资源管理体系中。然而,日本的尝试很明显并没有成功。

日本跨文化咨询公司创始人罗谢尔·科普认为,日本没有创造出让个人追求自己梦想的机制。日本的公司结构以及他们的人力资源管理模式,加剧了日本员工敬业度低的问题。

罗谢尔称,日本的员工加入的是一家公司,而不是一份特定想要从事或者感兴趣的工作,工作的分配由公司决定,而这种决定不一定要考虑个人学习的专业或工作兴趣所在,而无论员工是否想要这份工作或对这份工作是否感兴趣,他们都要欣然接受这份工作。

罗谢尔认为尽管有一些日本公司通过内部搜索员工的工作兴趣来填补空缺的职位,但这只是特例,并不是人力资源实践的常态,日本人力资源部门根本没有能力充分了解员工的技能和兴趣,仔细将他们与职位进行匹配。

当兴趣与工作不匹配的时候,员工就很难在工作中找到乐趣。盖洛普对142个国家的2022年员工研究显示,当问及他们是否享受每天的工作时,大多数日本员工(76%)表示他们享受其中,虽然这个比例看起来挺高,但却是落后于绝大多数调研对象:在142个国家中,日本处于倒数第三,且落后七国集团(G7)的其他成员国。G7集团自称是世界上“最发达的民主国家”组成的团体。

03 跳槽还是躺平?

当然,如果不满意这份工作,缺乏工作乐趣,对工作没有热情,那么员工换份工作就好了,但跳槽也会有顾虑,比如自己所从事的职业工作选择多、就业市场前景广阔、薪资待遇等等。

盖洛普的报告显示,当问及员工是否认为他们的职业有很多工作选择时,73%的日本员工回答是肯定的。这个结果相对比较乐观,也让日本在所有接受调研的国家中接近中间的位置。这个指标反映了员工对自己职业的流动性和灵活性的态度。显然,日本的员工对自己所从事的职业还是比较有信心的。

但当被问及他们是否认为现在是在本地找工作的好时机时,只有25%的日本员工给了肯定的回答,远远低于53%的全球平均水平。这个指标则反映了员工对当地就业市场是否有信心。显然,日本的员工对本地的就业市场则持悲观态度。

这种反差看似很迷惑性。不过,这样理解或许就更通俗些:日本人对自己的技能和资质有信心,而外部经济因素却制约了他们跳槽的决心。

总之,日本的劳动力市场缺乏流动性。

正如罗谢尔·科普所说,缺乏流动性的劳动力市场阻碍了日本人去更换一份真正感兴趣、真正充满热情的工作,因此大量日本人被锁定在他们没有兴趣或热情的工作上。那么在这种情况下,日本的员工有多大的概率会积极投入到工作中?这与躺平又有何区别?

04 拧巴

罗谢尔·科普曾与日本企业客户的一个中层管理人员讨论过工作兴趣的问题,那位经理说:“有时,这不仅仅是因为公司没有给员工机会去做他们感兴趣的事情,更是公司似乎有意阻止员工做他们想做的事。”

他谈了自己的经历。

这位经理更喜欢做技术工作,所以告诉公司他想继续从事技术岗位,不做管理层,但公司上层回答是:“我们计划让你当经理”。在这家日本公司看来,他对经理职位的拒绝、他对技术工作的坚持是对公司忠诚的表现,而公司想把这种忠诚展示给公司的员工们,这要比员工的兴趣更重要。这位热爱技术工作的日本员工最后也接受了公司的安排,成了一名公司的中层管理人员。这位经理感叹道:“我当时真应该聪明点儿。如果我要是告诉他们我真想当经理啊,那么他们估计就会让我留在技术工作岗位上了。”

对自己信心十足,却没有跳槽的决心;想干技术活,却接受了管理工作;想员工忠诚,却无视员工的兴趣。总之一个词:真拧巴。

在这种拧巴的状态下,敬业精神不一点点消磨殆尽才怪吧。

Japan's Workplace Wellbeing Woes Continue

By Hui Nemeth , Dr. Alden Lai Sept 7, 2023

Japanese workers are among the least engaged workforces in the world, according to Gallup's recent State of the Global Workplace report. A mere 5% of Japanese workers in 2022 were engaged at work -- which means they are involved in and enthusiastic about their workplace -- contrasting sharply with the global average of 23%.

Japan's engagement rate has remained consistently low by global standards since 2009, the first year such data were available, fluctuating between 4% and 8%. It compares poorly against other high-income economies and against its geographic and culturally aligned neighbors.

In 2022, Japan’s engagement rate is less than one-third of the 18% average for workers in fellow Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member states. This gap has been widening over the past decade, stretching from eight percentage points in 2009 to 13 points by 2022. Engagement levels in Japan are also typically lower than those in East Asia, where 17% of workers were engaged in 2022.

According to Gallup’s research, employee engagement is strongly connected to people’s wellbeing. Those who are genuinely engaged are thriving at work and playing a key role in driving the organization toward its goals.

Conversely, not engaged employees are those who are investing time but not energy or passion into their work. They put in the minimum effort required and are minimally productive. They are more likely than engaged workers to be stressed and burned out.

In Japan, 73% of workers are not engaged at work in 2022, compared with the global rate of 59%. Differences by gender only add to the situation’s complexity. Female workers in Japan are more likely than male workers to be not engaged (78% versus 69%), emphasizing a need for more inclusive policies.

Fewer Japanese Workers Than Average Enjoy What They Do

Given their relatively low engagement levels, it’s perhaps not surprising that Japanese workers are less likely than average to like what they do at work. Gallup, in partnership with the Wellbeing for Planet Earth Foundation, asks workers if they enjoy the work they do every day. The majority of Japanese who are employed for an employer -- 76% -- say they do, but this ranks Japan in the lowest third among 142 countries surveyed in 2022, and lags behind all other G7 countries.

Work enjoyment measures something different compared with more traditional metrics such as job satisfaction and employee engagement. While all of these are likely related, enjoyment is specifically how someone feels at work; satisfaction is how content they are; and engagement is how involved and enthusiastic they are with their workplace.

Understanding whether employees enjoy their work helps identify areas for improvement within the workplace and reveals underlying issues that may affect company culture. For example, low work enjoyment might point to a misalignment between employee values and organizational culture or highlight a need for more diverse and stimulating work assignments. It might also point to a need for cultivating meaningful relationships and building a supportive team environment, human connection or friendship.

Focusing on enjoyment in work also helps connect data with employees' sense of purpose, and how they themselves contribute to their overall wellbeing. As previously reported, those who enjoy their jobs rate their lives higher. When employees derive joy and satisfaction from what they do, it positively affects their mental and emotional state, and it is directly tied to higher wellbeing.

Career-Choice Perceptions and Job Market Confidence

Gallup and the Wellbeing for Planet Earth Foundation’s survey also explores whether people feel they have many choices in the type of work they can do. Interestingly, 73% of Japanese employed for an employer reported that they do, positioning Japan closer to the middle of all countries surveyed.

However, Japanese employees' outlook on the job market suggests they see options as somewhat limited in the near term. When asked if they believe it’s a good time to find a job where they live, just 25% of Japanese workers believed it was a good time, a figure significantly lower than the global average of 53%.

While the former metric provides a picture of how mobile and flexible people perceive their careers to be, the latter question assesses employees’ confidence in their local job market. The contrast between perceived career mobility and confidence in the job market is intriguing. While people in Japan may feel empowered in their skills and qualifications, they may at the same time feel constrained by external economic factors, including the overall economy, systemic issues in labor regulations, and a mismatch of skills and opportunities.

In addition, Japan's traditional “lifetime employment” culture (Shūshin koyō), though less prevalent now, may still be playing a role of shaping employee mindsets. This legacy could instill a sense of loyalty to an organization, potentially discouraging enthusiasm for change.

Japan’s Stressed Workforce

Managing workplace stress is vital for employers. Gallup World Poll asks people about their negative experiences in general, including anger, sadness, stress, worry and physical pain. Among the employed population in Japan, 42% reported experiencing stress during much of the previous day.

Since 2008, more of the Japanese population has consistently reported experiencing “stress” than any of the other negative experiences. Although experiences of worry are as common as stress worldwide, in Japan, as in many high-income countries, stress is a far more common emotion.

While stress can originate from a variety of sources, Japan's workplace culture, known for long hours, societal pressure against taking holidays, and rigid hierarchy, likely contributes to stress in the workplace. Addressing these issues could cultivate a positive and supportive workplace environment, mitigating stress and enhancing overall wellbeing.

The Road Ahead

Workplace wellbeing in Japan is not merely a theoretical concern but an essential aspect of organizational vitality. The unique challenges of low engagement, limited enjoyment, low confidence in job climate and high stress levels present both obstacles and opportunities.

It's vital for employers, policymakers and leaders to recognize and prioritize workplace wellbeing, shaping strategies that resonate with the intricate nature of this concept. Understanding and responding to these interconnected facets will be crucial in nurturing a dynamic, content and driven workforce, ultimately contributing to a more resilient and productive work environment in Japan.

Hui Nemeth is a Senior Consultant at Gallup. She leads Gallup’s partnership with the Wellbeing for Planet Earth Foundation through the Global Wellbeing Initiative project.

Dr. Alden Lai serves as an executive adviser to the Wellbeing for Planet Earth Foundation. He leads the Global Wellbeing Initiative project at the Foundation. Dr. Lai is also an assistant professor of public health policy and management at the School of Global Public Health and an affiliated faculty member at the Stern School of Business, New York University.

Japan’s disengaged workers

https://japanintercultural.com/free-resources/articles/japans-disengaged-workers/

The consulting firm Towers Perrin published a study entitled “Winning Strategies for a Global Workforce,” which examined how companies can attract, retain, and engage employees for competitive advantage. The study was based on a survey of workers from seventeen countries in Asia, Europe, and North and Latin America.

Reviewing the results of this study, one measure stood out – the one involving “engagement.” Engagement is defined as “employees’ willingness and ability to help their company succeed, largely by providing discretionary effort on a sustained basis” – in other words, willing to go the proverbial “extra mile” regularly.

Although the study’s authors point out that cultural differences in response patterns make comparison of the results for individual countries difficult, I couldn’t help noticing that Japan had extremely low levels of employee engagement compared to the other countries surveyed. 41% of the Japanese respondents were “disengaged” – only India had a higher percentage of disengaged, and apart from India no other country had more than 29% disengaged (the global average was 24%). And only 2% of the Japanese were “highly engaged” – with the next lowest percentage of highly engaged being in India, with 7% (the global average was 14%). Even when accounting for cultural differences, Japan appears to be a significant outlier on this scale, and that spells danger for Japanese companies in global competition.

I am not surprised to see these low levels of engagement, because for the past several years more and more Japanese who I meet – from corporate executives to newspaper editors to academics – have been telling me the same thing, that Japanese “no longer have a dream.” After World War Two, the country had a collective dream of rising from the ashes. But after that was accomplished, the mechanism was never created to enable individuals to pursue their personal dreams.

The structure of Japanese companies and how they manage human resources intensifies this problem. Japanese join a company, not a particular job, and the company decides where to place them. Job assignments do not necessarily take into account what a person studied, or what they want to do. Employees are expected to cheerfully accept whatever job they are given, whether or not they wanted it or have any interest in it. No wonder so few Japanese are engaged in their work! Although there are examples of companies conducting shanai boshu (internal searches where employees apply for a job of interest to them) to fill open posts, this is something special and not the normal human resource practice. Japanese HR departments are simply not equipped to learn enough about employees’ skills and interests to match them carefully to positions, and the lack of a fluid external labor market prevents Japanese from seeking work of interest outside their company. As a result, large numbers of Japanese are locked into jobs in which they have no interest or enthusiasm.

Immediately after reading this study, I happened to have lunch with one of my clients, a Japanese middle-manager, and shared with him my thoughts on how Japanese companies fail to give employees the opportunity to pursue the work that most interests them. His reaction was surprising: “Sometimes it’s not just that the company fails to give employees the chance to do what they are interested in, it seems like companies purposefully keep employees from doing the work they want to do.” I asked him to elaborate, and he cited his own example. “In my case, I preferred doing the technical work, and told the company that’s what I wanted to continue doing. The response was ‘Hmm, well, we plan to make you a manager.’ From the Japanese company’s point of view, the loyalty that a worker shows by continuing to work hard even after they have been denied what they wanted is something beautiful. They want to see workers display that type of loyalty. It’s almost perverse the way they seek to thwart people from doing what they really want to do. In my case, I should have been smarter. If I had told them that I really wanted to become a manager, they probably would have left me in the technical area.” This seems like a somewhat extreme view, and it’s hard to believe that all Japanese companies would purposefully follow this kind of policy. However, I can certainly imagine it happening in some cases, and the sad fact is that in many Japanese organizations there are no checks against managers behaving in this way.

This same client offered another interesting insight, on the connection between the lack of engagement and one of Japan’s current social problems, karoshi – death from overwork. Perhaps, he posited, Japanese resist becoming engaged in their work because they fear that being engaged requires throwing themselves so completely into their work that they will be unable to extricate themselves from it and end up completely overwhelmed and working themselves into the ground or even to death. Again, a rather dark thought, but it makes sense that young Japanese would resist the extreme sacrifices that many Japanese companies seem to demand of their employees. The growing numbers of NEETs (young people not in education, employment, or training, living off their parents while they figure out what to do) in Japan may also be a reflection of this unwillingness to engage fully in work. For NEETs, even taking a job is more engagement than they are willing to do.

Whether or not you embrace the rather depressing views of this particular client of mine, it does seem clear that lack of engagement is a serious problem for Japanese companies. In the past, the skillful use of human resources was one of the ways that Japanese firms rose to their top of their industries, and built the country into an industrial powerhouse. And as a country with few natural resources, Japan needs to effectively utilize its human resources. However, human resource management practices in Japan have not evolved to match the current needs of industry. Treating employees as interchangeable parts, and demanding absolute loyalty and extreme self-sacrifice is not a good strategy for an affluent society where an increasing number of people need to be knowledge workers. What is needed now is for Japanese companies to find a way to inspire workers, and to fully utilize each person’s individual unique talents. This will require no more than a revolution in how human resource management is conducted in Japan.

State of the Global Workplace: 2023 Report

https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace.aspx

This annual report represents the collective voice of the global employee. In this year's report, we examine the global rise in employees who are thriving at work, even as worker stress remains at a record high.

"What can leaders do today to potentially save the world? Gallup has found one clear answer:Change the way your people are managed."

JON CLIFTON | CEO, GALLUP

Explore Key Findings

Although employee engagement is rising, the majority of the world's workers are still quiet quitting. An improving job market may encourage those workers to quit for real.

- 1Employee engagement reached a record high in 2022.

- 2The majority of the world's employees are quiet quitting.

- 3Employee stress remained at a record high.

- 4In 2022, the world experienced a surge in job opportunities.

- 5Over half of employees are actively or passively job seeking.

- 6Engagement matters more than where workers work.

- 7"Quiet quitters" know what they would change at work.

Employee engagement reached a record high in 2022.

"I enjoy my work, and I would miss something if I didn't have to work, even if the money stayed."

- HARTMUT, 63, IT SECURITY MANAGER, GERMANY

After dropping in 2020 during the pandemic, employee engagement is on the rise again, reaching a record-high 23%. This means more workers found their work meaningful and felt connected to their team, manager and employer. That's good news for global productivity and GDP growth.

Spot the trends. Explore Gallup’s global indicators on employee engagement.

The majority of the world's employees are quiet quitting.

"I just don't feel like there's a lot of room for me to grow internally."

- MICHELLE, 27, INDIVIDUAL CONTRIBUTOR, UNITED STATES

Quiet quitting is what happens when someone psychologically disengages from work. They may be physically present or logged into their computer, but they don't know what to do or why it matters. They also don't have any supportive bonds with their coworkers, boss or their organization.

Nearly six in 10 employees fell into this category.

When combined with actively disengaged employees, low engagement costs the global economy $8.8 trillion dollars, or 9% of global GDP.

Employee stress remained at a record high.

"By the time I'm done with work, I’m so exhausted that some days I don’t have the energy to hold a conversation. So, over time, I've had family [and] friends accuse me of not being socially receptive when they try to reach out."

- IREGUME, 27, CONSULTANT, NIGERIA

Worldwide, 44% of employees said they experienced a lot of stress the previous day. This is the second year in a row worker stress reached record levels.

Employee stress rose in 2020, likely due to the pandemic. But employee stress has been rising for over a decade. Many factors influence stress, but Gallup finds that managers play an outsized role in the stress workers feel on the job, which influences their daily stress overall.

Spot the trends. Explore Gallup’s global indicators on employee wellbeing.

In 2022, the world experienced a surge in job opportunities.

Every region of the world but one saw an increase in the number of workers who said now is a good time to find a job where they live. The exception was the United States and Canada region, which saw its own surge in job opportunities the year before.

The increase in available jobs signals that the world economy is open for business. But employers will have to pay more attention to retaining their most talented workers as a result.

Spot the trends. Explore Gallup’s global indicators on employee retention & attraction.

Over half of employees are actively or passively job seeking.

"I used to come home thinking only about work. I used to unload everything on my husband. Totally unsatisfied. Then, when I changed roles, it got a little better, but I was still unsatisfied."

- RAQUEL, TRANSPORTATION ANALYST, BRAZIL

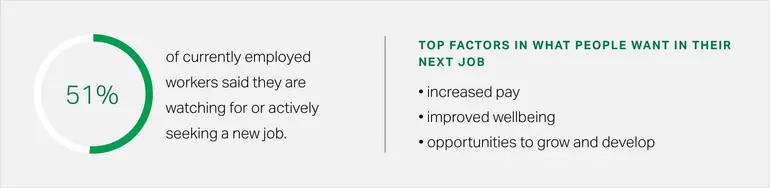

Across the countries and areas surveyed, 51% of currently employed workers said they are watching for or actively seeking a new job.

Increased pay is a top factor in what people want in their next job. But improved wellbeing and opportunities to grow and develop are also highly prized by job seekers.

Engagement matters more than where workers work.

"I wish my manager was more present."

- FRANK, MECHANICAL AND CHEMICAL TECHNICIAN, BRAZIL

For organizations with remote-capable employees, there has been an ongoing debate. Which is better: Working remote, hybrid or fully on-site? Remote work can provide greater flexibility and eliminate commuting stress. On the other hand, being on-site provides opportunities to bond, collaborate and mentor.

Gallup analysis finds that engagement has 3.8x as much influence on employee stress as work location. How people feel about their job has a lot more to do with their relationship with their team and manager than being remote or being on-site.

3.8xas much influence on employee stress as work location

”Quiet quitters” know what they would change at work.

“My work does not give me the opportunity to go to church, visit family members, or travel for a while.”

As part of our survey, we asked respondents, “If you could make one change at your current employer to make it a great place to work, what would it be?” Overall, 85% of responses related to three categories: engagement or culture, pay and wellbeing.

41%Engagement or culture

28%Pay and benefits

16%Wellbeing

Many respondents said they would like more recognition, opportunities to learn, fair treatment, clearer goals and better managers.