笨狼发牢骚

发发牢骚,解解闷,消消愁

中国12月社融增量2.37万亿 新增人民币贷款1.13万亿 - 华尔街见闻

Ukraine also has access to NATO procurement system. In selected aspects, it is already a member of NATO. https://t.co/UvfZXLgmTn

— Leonid Ragozin (@leonidragozin) January 15, 2022

刘海影:面对内需不足局面,应坚定不移地走市场化改革开放路线,以是否改善民企处境、是否有利于建立民间对政策规则的稳定预期为改革标准。

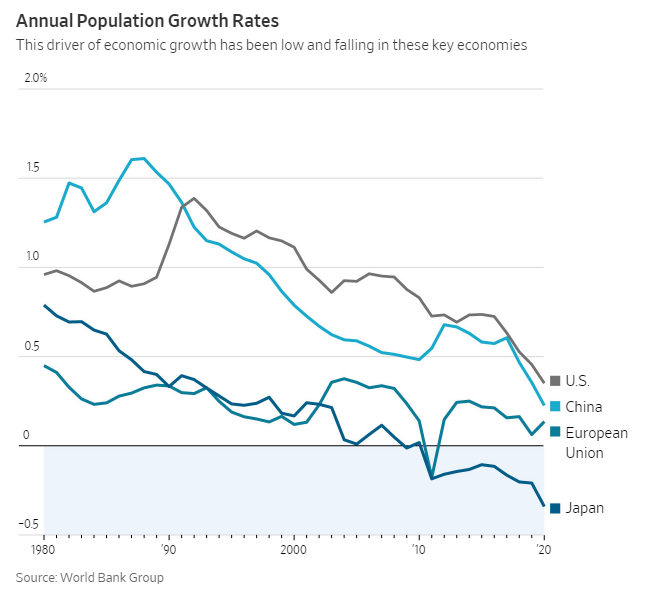

2021年年底的中央经济工作会议指出,“我国经济发展面临需求收缩、供给冲击、预期转弱三重压力”。三重压力中,需求收缩无疑是最严重的挑战,供给冲击不过是一次性事件,预期转弱本就是对需求收缩的认知映射。曾几何时,中国经济引擎的轰鸣马达响起的是“钱太多”的回音,世界第一大消费市场的头衔也是吸引跨过公司热情涌入的头号理由,当前中国却需要直面需求不足的挑战,原因几何?

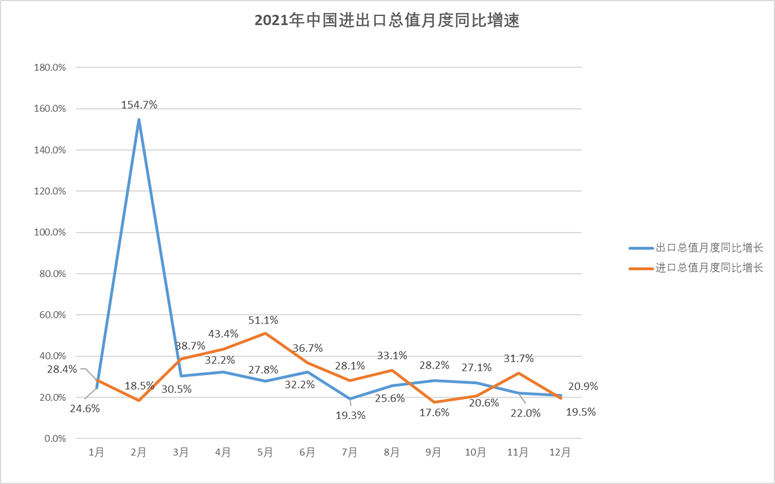

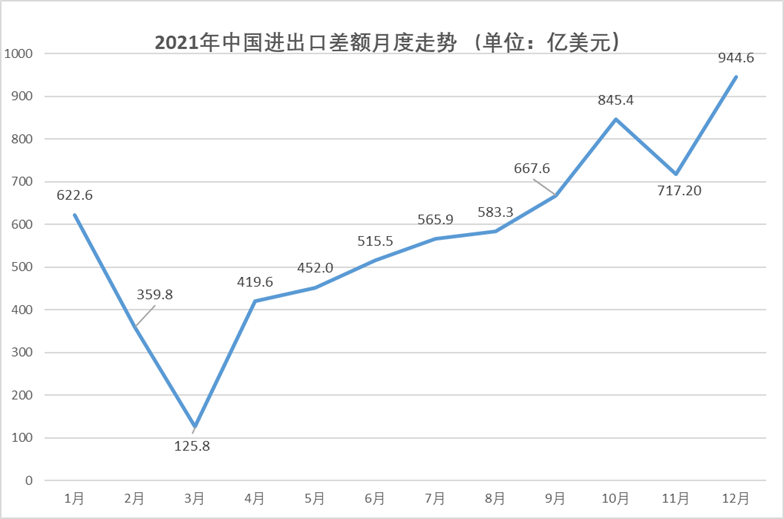

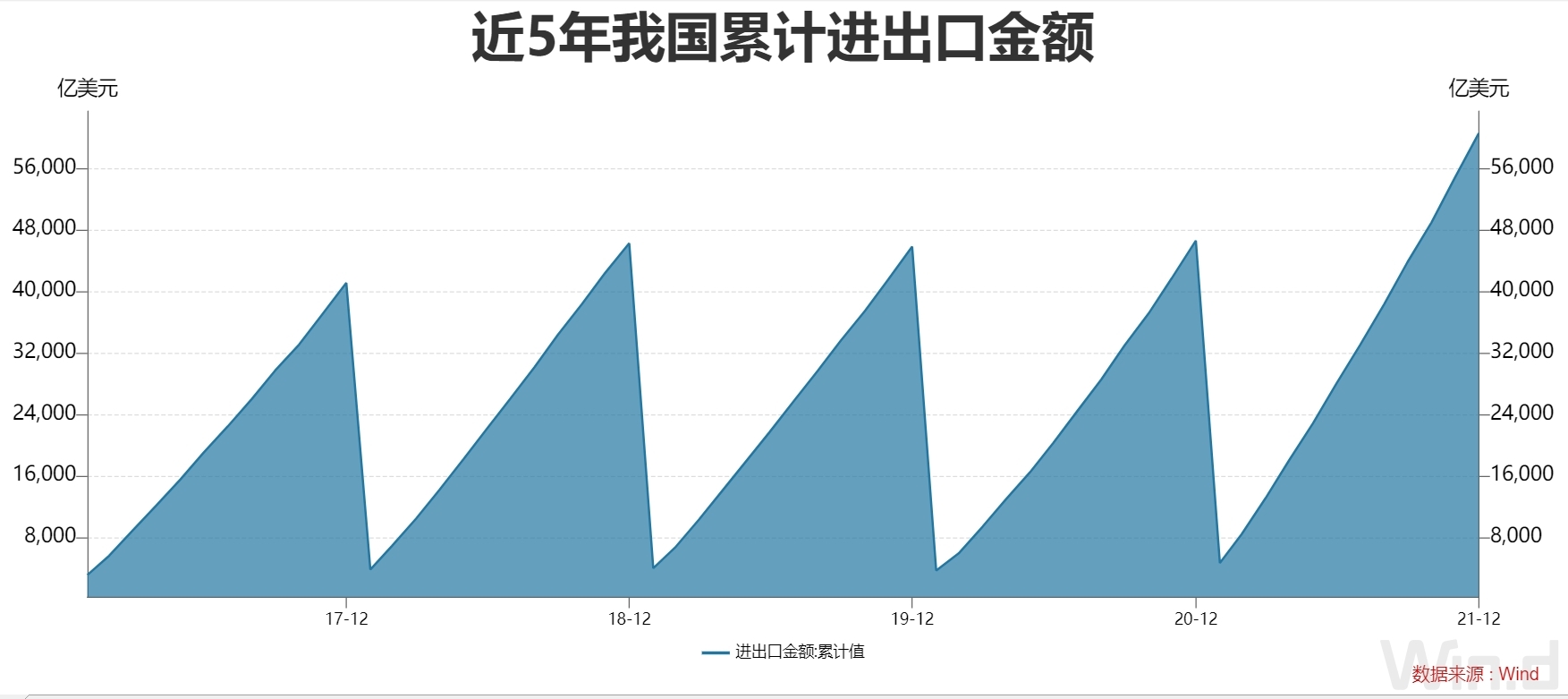

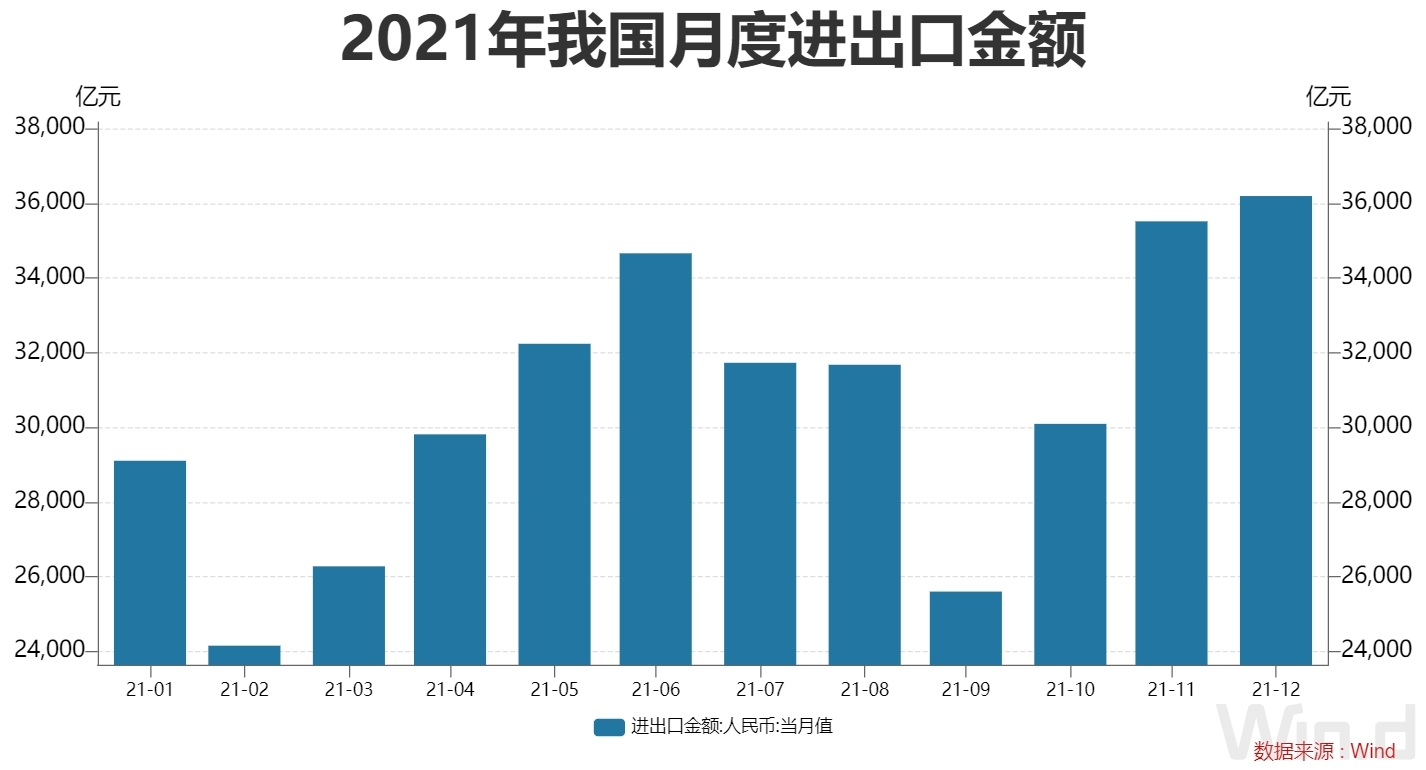

疫情不是充分的理由。对比一下,疫情肆虐的美国,消费迭创新高,带动美国通货膨胀创出近40年新高;很多其他国家同样如此,以至于2021年全球货物贸易量将增长10.8%,全球通货膨胀率也创出10年新高。

从宏观经济学角度看,需求不仅是消费,也包括投资与净出口;需求不足也不是绝对概念,而是相对于中国经济庞大的供应能力而言,需求有所不足。从某个角度讲,需求不足反证了中国经济的成功,表明中国经济体供给能力维持了持续多年的高速扩张。在理想情况下,持续扩张的供给能力产生持续增长的收入,并带动持续增长的需求,达成一个完美平衡(所谓的“黄金律”)。在这样一个完美状态中,不存在需求不足。事实上,在中国经济腾飞的前35年,这一完美状态几乎就是现实——虽然欠缺的那一点,正好如滚雪球般导致了今日需求不足的事实。

那么,中国经济的需求不足问题,成因何在?

房地产结构性问题

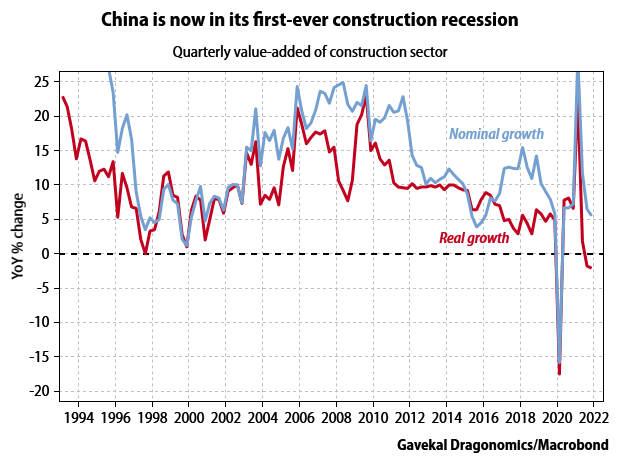

一个可能的答案是房地产行业的结构问题。在批评者眼中,中国超高的房价收入比水平在挤出了居民消费之余,抬高了实体经济运行成本,抑制了实体投资。在去年房地产形势急转直下之后,经济学家也立即指出,房地产行业的直接与间接贡献,占据了中国GDP的25%~30%左右份额,房地产行业衰退迅速导致实体经济的不景气,构成需求不足的最直接原因。

从数据上看,中国房地产行业的问题可以以“四高”来概括:

房地产行业在建规模巨大,按照商品房平均售价计算其建成价值达到100万亿元,占GDP比例从20年前的15.5%上升到现在的88%;

这一巨大的在建规模由房地产企业巨大的总负债来融资建设,其数额按照全行业总资产减去净权益来计算,达到95万亿元(含预付款等无息负债与贷款、债券等有息负债),占GDP比例从20年前的19%上升到现在的85%;

而房企之所以愿意并有能力进行如此大规模的负债建设,是受到居民同等力度的购买行为的支持,而后者以快速增长的居民负债为支撑,其规模近年来快速上升,到2021年占GDP比例达到60%,占居民可支配收入比例超过100%。

上述三高推动中国房价多年来快速上涨,以上海为例,按照numbeo提供的数据,上海的房价收入比高达43倍,对比之下同样作为全球金融中心的美国纽约市该值仅为10倍,上海房价在这个意义上是纽约房价的4.3倍。

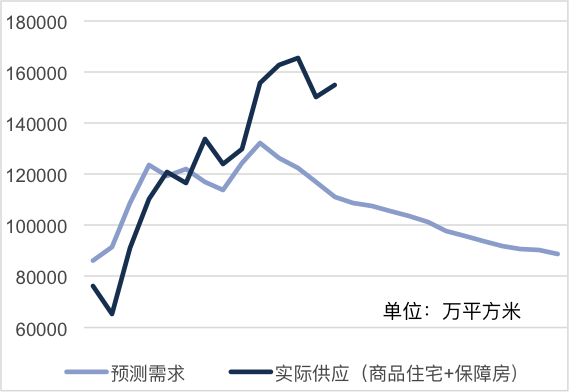

这种情况下,房地产行业持续多年的超级繁荣事实上建立在巨大的供需不平衡基础上。我们可以从每年新结婚人数、新市民人数所对应的刚需以及市民改善型需求三个角度,来粗略匡算中国家庭的住宅需求,按照行业人士谭奎提供的数据,在一定假设下,中国居民住宅需求变化轨迹如图。可以看出,2013年之前,基本格局是供不应求,从2013年开始,住宅供给超过了住宅需求,2015年开始的棚改新政进一步放大了供需缺口,到2021年这一缺口达到惊人的4.4亿方,也构成了房地产形势转折的最大背景。按照这一估算,住宅需求将在10年左右时间跌至9亿方左右,相比较于2021年15.5亿方米的供给缺口41%。

多年繁荣之下,中国房地产行业、建筑行业中住宅建筑部分对中国经济直接与间接贡献占据GDP比例高达27.9%,超过美国、欧洲等国水平的2倍有余。

换言之,与大家的认知相反,事实上中国经济本可能在更早的时间就展现出需求不足问题,而房地产行业与居民的加杠杆运动创生了超前的需求,从而延后了这一问题的暴露。

现在,房地产行业在2021年下半年的下滑,只是对过去多年额外需求的修复。考虑到中国居民债务占中国居民可支配收入(按照国民经济资金流量表计算,而不是统计局抽样调查数据,后者低估了中国居民可支配收入水平)之比超过100%,在居民下调其未来收入增速的条件下,可以预期中国居民进一步加杠杆的能力与意愿都将大幅下滑,进一步暴露出房地产行业供需缺口的巨大。这一缺口的调整压力保守估计将会持续10年以上,以每年约5%的速度压低房地产行业经济产出,并透过其直接与间接的拉动作用,对GDP增速形成大约-1.2%的拖累,迥异于之前10年平均1.5%的正贡献。这种拖累,既体现为消费需求,也体现为投资需求。

中国经济目前以及未来遭遇需求不足的困扰,房地产行业的透支及其后遗症是重要原因。也正因此,政府出台“房住不炒”和“三条红线”的政策基调,来促进行业艰难的去杠杆和出清再平衡。

资源配置问题

然而,在我们的分析中,房地产行业的结构问题虽然重要,却并非中国经济需求不足问题最大的根源。实际上,中国经济需求不足问题最大的根源,在于近年来中国资源配置效率的降低。

中国经济具备巨大的后发优势,在理想状态下,通过学习、创新并固化于投资之中,新技术有机会源源不断地渗入经济运行,提高生产能力、生产效率与劳动生产率。这将保证收入与需求持续上升,形成与产能相匹配的消化能力。这里面的关键在于,中国的经济体制必须正确地配置资源,令尽可能多的投资属于有效投资。

按照定义,有效投资是指有能力支付所有上游行业成本、尤其是人力成本之后,仍旧能够挣取合格利润率的投资。对成本的支付是收入创造与需求衍生的同一过程,而合格利润率保证了可能的增长机会将被穷尽利用。这样,假设一个经济体的所有投资都是有效投资,那么,投资既扩张产能,也增加收入,两者并行不悖,古老的萨伊定律将在动态中维持生效。

然而,现实中很多情况将会阻碍这一理想情况的出现。近年来,中国资源配置效率有所降低,投资创造收入的能力下滑。2008年美国金融危机之后,中国政府强调国有经济的控制力,从4万亿、供应侧改革、棚改房新政到2021年的监管风暴,几乎每年均有重大措施出台。从数据上看,中国的投资回报率从2007年最高点16%持续下滑,到2016年跌至4.5%附近,随后继续小幅走低。

这个过程中,中小型民企经营挑战加剧。从PMI指标看,从有数据的2011年以来,大企业PMI指数在95%的时间高于50荣枯线,而小企业PMI只有12%的时间高于荣枯线,两者差距在2016年底达到最大值,直到最近仍旧高达3个点左右。由于国企一般都是大企业,中小企业困境也就是民企困境,对于民企而言,要么在”内卷”的行业格局中红海竞争,要么进军国际市场,要么在政府监管尚来不及发力的新经济领域冒险一搏。在金融资源、政策监管、行业准入、资源倾斜等方面它们与得到政府支持的大型国企相比,遭遇很多现实困难与体制性压力,在投资回报率、技术进步与扩张等方面,近年来迭次减速。民企固定投资增速从2007年47%的高位,下行到疫情冲击前(2019年底)的-2.6%。

而得到更多资源支持与政府培植的大型国企,占用70%的金融资源,与近年来负债高速扩张的地方政府一道,弥补了民企投资需求的不足,成为支撑投资增长的逆周期力量。但国企与地方政府的投资扩张,其投资中有大量项目属于无效投资,并且由于退出机制的无效,即使是已被证明无效的产能,也可以得到源源不断的融资支持而维持,或者依靠垄断地位而维持(压低下游中小型民企的利润),因而推升中国经济的债务比率、压低下游及中小型民企投资回报率。同时,国企与地方政府投资的就业密度远低于民企投资,创造就业岗位与收入增长的能力不足。

无效投资多、无效产能退出缓滞、投资回报率低,基本上是一体三面,其经济后果是无法创造足够的高新劳动岗位及其所决定的收入与需求增长,反过来,疲弱的终端需求进一步恶化了产能过剩与僵尸企业问题。换言之,国企与地方政府规模巨大的无效投资,在当期创造需求,长期内则抑制需求。

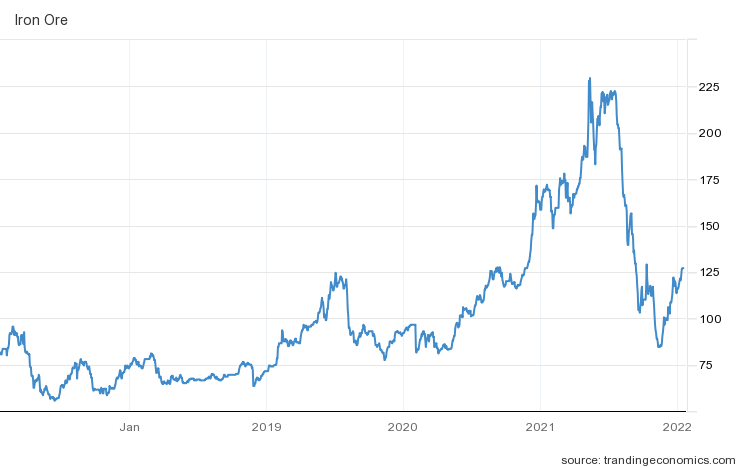

2021年,上述问题得到充分暴露。之前数年,资源品行业出现了成规模的产能向国企集中,随后经历了投资不足与创新减速,行业垄断与产能缺口随之涌现,叠加碳中和政策等其他因素,PPI在2021年大幅上涨了10%。出厂价格的大幅上涨有力地推动了上游行业、占据资源优势的大型国企盈利上升,2021年因此成为利润大年。问题是,PPI上行并未驱动CPI同步上行,PPI-CPI剪刀差持续扩张,上游成本上升没有伴随以终端需求提升,中下游行业、民企以及中小型企业成为游戏输家。

从数据上看,从2009年开始,PPI-CPI剪刀差与国企-民企利润增速剪刀差高度同步,揭示这一现象已经重复多年,反映出利润与资源配置对上游行业与国企倾斜,PPI上升驱动的加库存运动中,中小型企业对ROE持续改善信心不足,企业并未同步提升其扩张欲望,投资增幅远低于利润增幅。

由于民企创造了80%的就业,民企的不景气直接影响到居民收入增速,到2021年年末个人可支配实际收入2年平均增速下滑到4.1%,个人实际消费开支2年平均增速跌至2.2%,社会消费零售总额2021年年末按照环比联乘值计算实际当年同比增速跌至1.5%。内需不足的挑战由此浮出水面。

面对内需不足,政策应该做什么?

从上面的分析可以看出,面对内需不足局面,切忌头痛医头脚痛医脚。

一个容易的药方是加大政府主导的投资,依靠政府投资来填充内需,例如加大地方政府主导的基建投资或者新基建投资。如前所述,这些投资许多不具备合格的投资回报率,大部分项目投产之日,也就是产生负现金流之日,事实上,地方政府投资项目的整体现金回报率无法覆盖投资利息,不仅产生了地方政府巨额负债问题,也错配了经济资源,恶化了资源配置效率,对改善中下游、中小型民企处境收效甚微。今日内需不足窘况,正是往日不断刺激投资的结果。同时,地方政府在多年透支之后陷入财务窘况之时,可能浮现的加大税费征收冲动,对地方中小企业发展绝非福音。从这个角度出发,合理的基建项目应该上马,但不应该为投资而投资。

另一个药方是设法加大房地产投资,过去这似乎是一抓就灵的妙方。然而,房地产过度发展无助于缓解居民收入增长乏力问题。整个房地产行业,过去10年总经营收入90.6万亿,其中一部分转化为企业盈利,合计为11万亿;一部分支付了土地之外的成本,约27.2万元;最大一笔去向是支付地方政府土地拍卖成本,合计约52.4万亿元。很明显,不是房地产发展了居民收入就增加了,而是居民收入增加了(并预期将会持续增加)才能够负担高昂土地成本。鉴于居民负债之高已经影响到居民当期开支,在当前局面下,重新刺激房地产市场发展对需求的扩张与收缩效应很可能将互相抵消,总体而言,刺激房地产进一步过度发展不仅将是危险的,对于解决需求不足问题也将是无效的。

还有一个药方是在共同富裕口号下执行强监管政策、通过强化征税提升实际税率。背后的一个理由是,由于贫富不均,消费倾向高的低收入阶层无钱可花,而消费倾向低的高收入阶层为富须为仁。如果实现了更为均等的财富分配,中国居民的消费倾向将有所提升,缓解需求不足问题。

对此,需要问的问题是,挫伤大型民企信心的举动是否有利于提升居民收入。成功民企的股东(及其创始人)在绝对财富数量上的优势令人心生不平,但事实上,他们的开支在其个人财富中的占比相当低(这是所谓低消费倾向的含义),在更大的意义上,他们是财富的管理者而不是使用者。财富是资产的另一个名字,唯有能够带来未来合理利润的资产,才能够被记为财富,而能带来未来合理利润的投资,就是我们前述的有效投资,也就是涉及岗位创造、收入增长的经济活动。

从这个意义上讲,民企的成功——无论其规模大小,只要合法合规——都应该受到鼓励,它是居民收入增长的朋友而不是敌人。企业家用自己的财富承担创新失败的风险,如果他们的投资失败,经济扩张与收入改善的可能性就会落空,但这是探索发展机会必要的试错尝试,并且他们身上体现出来的贫富不均数据自然得以改善(富人变穷了)。换言之,民企与企业家进行的投资探索,我们应该乐见其成功。

实际上,近年来中国企业在新经济领域的成功,不仅极大地提升了中国的国力,也是中国居民收入增长、消费增加的重要推动力量,更可能是中国不错失未来技术革命(例如习近平主席最近强调的数字经济)的关键,其积极意义怎么估计都不为过。

同理,应该在降低税率、规范化收税的前提下,尽可能降低实际税负,而不是相反。与全球其他国家相比,中国的宏观税负处于一流水平,中国政府掌握的资源也远高于其他各国政府,这种情况下,需求不足并非由于实际税负不够高。

2022年开年情况看,消费增速已经跌至低水平,外需增速将大幅低于去年,房地产投资将会负增长,制造业投资增速将前高后低,增速难超去年,表明2022年将是困难巨大的一年。按照我们量化模型预测,2022年经济实际增速下滑幅度可能超出市场一致预期。困境不是一日炼成,脱离困境也不会是一日之功。此时此刻,必须首先认识到问题的严重性,其次对成因进行客观、准确剖析,并在坚强决心之下,采取正确举措。

那么,什么才是正确举措?一言以蔽之,就是坚定不移地走市场化改革开放路线,以是否改善了民企处境、是否有利于建立民间对政策规则的稳定预期为改革标准。

(作者为独立经济学家,维世资产管理(香港)有限公司宏观顾问。本文仅代表作者观点。责任编辑邮箱:tao.feng@ftchinese.com)

Why Is Russia Threatening to Invade Ukraine?(2021.12.16)

For Putin, the current standoff is a chance to overturn what he sees as an unjust post-Cold War order—and create a new one in its wake.

For the moment, a video call on December 7th between Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin seems to have avoided, or at least delayed, war in Ukraine. In the weeks prior, Russia had amassed an alarming number of ground forces and support personnel at the border, raising concerns of a looming invasion. As was the case before the first in-person meeting of the two Presidents in Geneva, in June, a cycle of escalation has seemingly given way to an opportunity for dialogue. Putin called the latest talks “open, substantive, and constructive.” But rather urgent questions remain: Why was a new round of conflict a possibility in the first place, and has the danger really gone away?

For Putin, Ukraine seems to be key not because he dreams of resurrecting the Soviet Union or enlarging the territory of modern-day Russia by force; rather, Ukraine presents an opportunity for Russia, once and for all, to reassert its geopolitical relevance. As Putin sees it, only the threat of war can reopen a conversation that, to many in the West, has long felt like settled history: the expansion of NATO eastward, the denial of a Russian veto on questions of regional security, and the underlying sense that Russia lost the Cold War. If Ukraine joins NATO, or is drawn into a de-facto military alliance with it, then Putin’s project has failed; if Ukraine is kept from doing so, Putin has fulfilled his historical role.

“After so many years in power, Putin sees himself, not Gorbachev or Yeltsin, as responsible for formulating the ultimate post-Soviet order,” Alexander Baunov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center, said. “In this sense, many events or facts that may seem to be historically irreversible are, from his perspective, mistakes that remain to be corrected.” For Putin, the United States is the counterparty with whom he can seek to fulfill this promise; Ukraine, as it were, is the host venue.

The current cycle of tensions with the West regarding Ukraine dates to 2014, when, in the wake of street protests that toppled Ukraine’s venal President Viktor Yanukovych, whom Putin backed, Russia annexed Crimea and sparked a would-be war in the Donbass, in eastern Ukraine. Although the conflict continues today, albeit at a low simmer, its most deadly phase, following an outright Russian incursion, was brought to a temporary end by the Minsk agreements, a set of peace accords reached in 2014 and 2015. Those agreements, signed at a moment of acute weakness for Ukraine, call for measures that, if fully implemented, would allow a large degree of autonomy for the Russian-backed enclaves in the Donbass. As a result, Kyiv would be hamstrung in pursuing an independent foreign policy—which is exactly what Russia wanted.

For this same reason, the Minsk agreements were destined to be a tough sell for Ukraine itself. Relations between Russia and Yanukovych’s postrevolutionary successor, Petro Poroshenko, quickly soured, especially as Poroshenko staked his legitimacy on an uncompromising and militaristic position in the Donbass. In 2019, Volodymyr Zelensky assumed the Presidency, promising peace. His earliest moves were aimed at easing tensions with Russia and withdrawing forces from frontline positions. The Kremlin viewed him favorably, at least compared to Poroshenko. Since then, as Zelensky was forced to deal with Russian intransigence, the fundamental impossibility of enacting the Minsk agreements, and pressure from nationalist factions and paramilitary battalions in Ukraine, he has adopted a more bellicose posture.

“If, for a while, the Kremlin saw in Zelensky the possibility of reaching an agreement, over the last year, it has become convinced this is not the case and that he’s no different than Poroshenko,” Andrey Kortunov, the director general of the Russian International Affairs Council, said. Having grown disappointed in two successive Ukrainian Presidents, the Kremlin became convinced that the only interlocutor with whom it can speak is in Washington, not Kyiv.

In February, Zelensky moved against Viktor Medvedchuk, an oligarch widely seen as the Kremlin’s point person in Ukraine. (Medvedchuk, who has a long-standing personal relationship with Putin, was appointed one of Ukraine’s chief negotiators for the peace talks in Minsk.) Zelensky’s administration ordered three television channels linked to Medvedchuk taken off the air and sanctioned Medvedchuk and his wife. A few months later, Ukrainian prosecutors charged Medvedchuk with treason and a court ordered him held under house arrest. The U.S. Embassy in Kyiv spoke favorably of Zelensky’s decision to shut down Medvedchuk’s networks. It’s possible to see Medvedchuk’s role as entirely pernicious and his removal from civic life as a long overdue turn of events for Ukraine. But, if you’re Putin, it might seem like a clear violation of the delicate status quo governing relations between the two countries, and a sign of the West’s hypocrisy on questions of rule of law.

Perhaps the most worrying development of all for the Kremlin was the slow creep of military equipment and weaponry from NATO states into the Ukrainian arsenal. Since 2018, the U.S. has sold hundreds of anti-tank Javelin missiles to Ukraine. Last March, the Pentagon announced a hundred-and-twenty-five-million-dollar military-aid package, which included armored patrol boats. Turkey has supplied the Ukrainian army with the same type of armed drones that proved decisive in Azerbaijan’s victory over Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh last fall; this October, Ukrainian forces used such a drone to destroy rebel artillery in the Donbass. In November, Ukraine signed a treaty with the United Kingdom that would allow it to buy British warships and missiles—an announcement that followed a tense moment last June, when the Royal Navy sailed a destroyer in the Black Sea, close to Russian-held Crimea, angering the Kremlin.

At a certain point, Russia came to fear that Ukraine, in its accumulation of NATO weapons systems, was becoming the equivalent of an unofficial member state. Given all that weaponry, what would keep NATO armies from establishing bases? And, with bases in place, why couldn’t they host NATO missiles, even nuclear ones that would directly threaten Russia and undermine its deterrence capabilities?

“The Kremlin has long ago accepted that Kyiv’s political line is going to differ from its own,” Fyodor Lukyanov, the editor-in-chief of Russia in Global Affairs and a respected voice in Moscow foreign-policy circles, said. Even if they don’t admit their own responsibility, officials in Moscow are not blind to the fact that, in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its role in propping up the war in the Donbass, Ukraine’s political culture will surely retain a strong anti-Russian element for some time to come. “But that doesn’t mean they don’t take very seriously the importance of insuring Ukraine’s neutral status, which, as they see it, means it cannot host any NATO military infrastructure,” Lukyanov said.

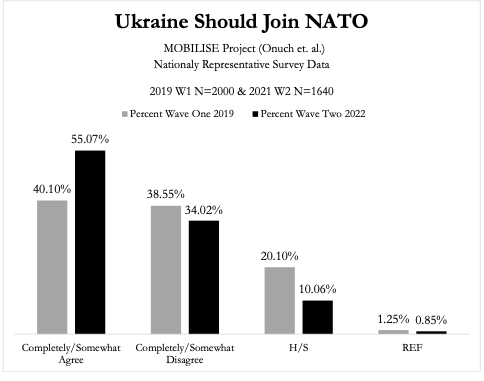

From Putin’s point of view, the real nightmare scenario is formal NATO membership for Ukraine. (As with so much of what Putin finds discomfiting in Ukraine, he has only himself to blame—in 2014, a poll showed that the idea of joining NATO had around fifteen to twenty per cent support among the Ukrainian public; today, that number is more than sixty per cent.) Since Biden became President, Zelensky and other Ukrainian politicians have been more vocal in pushing the matter. In January, Zelensky told Axios on HBO that he had one question for Biden: “Mr. President, why are we not in NATO yet?” Even if Ukrainian membership is not on the immediate agenda, the official position of NATO member states, the U.S. included, on the question of future expansion is unchanged: if potential new members meet the requirements and are interested in joining the bloc, no outside powers have the right to tell them they can’t.

“From the perspective of the West, the end of the Cold War gave way to the rise of a certain geopolitical order, with which everyone more or less agrees—except Russia, which every now and then gets upset for seemingly no reason,” Lukyanov told me. Only that’s not the view in Moscow, he explained. “The issue is not so much Ukraine but the underlying principle: if a military alliance seeks to expand, it has to consider the interests of those who are opposed.” Russia, in other words, can’t be expected to remain a passive observer of actions that it believes violate its core security concerns. “That’s the red line, and, if crossed, Russia will respond,” Lukyanov said.

For the first two decades of his rule, Putin saw his own geopolitical maneuvering as essentially reactive, a response to what he and the Russian policy élite viewed as long-standing Western efforts to weaken Russia. “In Putin’s reality, Russia was encircled and under threat, and was required to defend itself,” Tatiana Stanovaya, head of the analysis firm R.Politik, told me. But, throughout the past year, that dynamic has undergone a fundamental transformation. In mid-November, Putin gave a speech at the Russian Foreign Ministry in which he said that Western states do not respect Russian interests or ultimatums, and the only way to get them to do so is by keeping tensions high and threatening force. “He made clear that Russia will no longer stand around whining and complaining about the injustices of the world,” Stanovaya said. “It is ready to act, to use force to stand up for its position. This is a principally different Putin, and a different Russia.”

The current Russian military buildup along the border with Ukraine far exceeds the scale of what worried Western governments over the spring, in advance of the Putin-Biden summit in Geneva. U.S. intelligence officials told the Washington Post they believe Russia will, by early 2022, have in place a hundred battalion-tactical groups, equalling a hundred and seventy-five thousand troops. Citing a Western intelligence official, the Financial Times reported that Russia’s military deployment is “still missing some critical equipment and capabilities typically required for a sustained offensive” but that “these elements could be brought to the border rapidly if needed.”

Whatever the ultimate composition of Russia’s forces, their ability to overwhelm the Ukrainian military is not in doubt. “It’s hard to overstate the significance of how much military power they are putting together,” Michael Kofman, an expert on the Russian military and research director of the Russia Studies Program at CNA, a think tank, said.

Once such a sizable military force is in place, it comes to exert its own influence on events. “If you draw down such a public and heavy-handed deployment, people say you were bluffing or you were deterred—and both are losses for Putin,” Kofman said. He estimates that the Russian military has the logistical wherewithal and resources to maintain its current force along the border until the early spring, by which time Putin will have to decide whether to invade or back off.

That gives the Biden Administration a narrow window. In the days since Biden’s call with Putin, Russia has put forward a set of expansive, and unlikely, demands. The Foreign Ministry published a long list, calling on NATO states to formally retract a 2008 pledge that the alliance would one day admit Ukraine and Georgia, promise not to deploy certain weapons systems to states near Russia, and refrain from military drills and maneuvers near Russia’s borders.

Sergei Ryabkov, a Russian Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, said that, if NATO continues to expand, the country’s “response will be military.” He also said Russia will deploy intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Europe if NATO does not agree to return to treaty talks over banning such weapons. “This path must be traversed quickly,” Ryabkov said. One element of the U.S. position that somewhat buoyed hopes in Moscow is Biden’s promise to Putin that he would assemble a meeting of major NATO allies to address Russia’s concerns.

Even if the U.S. and other NATO members were ready to negotiate on these strategic questions, there is no realistic scenario in which significant progress, much less a formal agreement, could be made in the compressed timeline that Russia seems to be demanding. That may suggest that Putin is wagering, as Russian officials often boast, that Russia cares more about Ukraine than the West does—which means that, in the end, the West will cave so as to stave off a war it doesn’t want. After all, a Russian-Ukrainian war is a lose-lose for Western states: either they look feckless if they do nothing and Ukraine is defeated, or they feel compelled to intervene, risking a wider war with Russia that no one has the stomach for.

Or, more ominously, Russia is putting forward demands it knows can’t be met, in order to justify the invasion to come. In a wide-ranging essay on Russia’s new, more assertive foreign policy, the analyst and columnist Vladimir Frolov wrote, “The threat of the use of force against Ukraine cannot be infinitely convincing (and effective for achieving political goals) without actually using force.” Frolov wryly quoted a line attributed to Secretary of State Antony Blinken: “Superpowers don’t bluff.”

In any scenario, the current standoff is Putin’s chance to overturn what he sees as the unjust post-Cold War order and create a new one in its wake. But anyone who claims to know for sure whether he’s set on achieving that through war is engaged in a bluff of their own. In Chekhovian fashion, Putin has hung the proverbial gun on the wall—whether it, in fact, goes off or not in Act II is a climax yet to be written. “I have the sense that Putin sees a new grand agreement with Biden as the most preferable form of victory,” Stanovaya said. “War with Ukraine would be a desperate measure he would see as forced on him by circumstance—which doesn’t mean he won’t do it.”