笨狼发牢骚

发发牢骚,解解闷,消消愁《金融时报》US-China trade war prompts rethink on supply chains

Suppliers to Google and Hoover among those looking to shift production out of China

Steve Madden is shifting handbag production to Cambodia, Vietnam is sucking up some production for Hoover-maker Techtronic Industries and Google’s hardware maker Flex is seeking new production centres from Mexico to Malaysia.

The escalating US-China trade war is pushing China-based manufacturers and their US clients to rethink the complex and extensive supply chains that bind the world’s two biggest economies together.

“While China will remain an important part of our global manufacturing platform for the next decade, we have accelerated the ramp-up in other low-cost countries and the US,” said Joseph Galli, chief executive of Techtronic, which makes the majority of its power tools in China and generates three-quarters of its revenue from the US for products including Hoovers. “The focus on Vietnam in the short term is offsetting the future tariff impact we might see in the US.”

The Trump administration has so far levied 25 per cent tariffs on $50bn of Chinese industrial goods and is considering putting similar tariffs on another $200bn of Chinese exports, punishing Beijing for “unfair trade practices” including forced technology transfers and intellectual property theft.

Most consumer goods have been left off the tariff lists to reduce the pain felt by US consumers. But manufacturing and retail executives fear that, with Beijing and Washington both refusing to concede, the range of affected products could widen.

Clara Chan, the head of a lobby group for 150 Hong Kong manufacturers that employ more than 1m people in China, said that while factory executives were used to managing disruptions from rapid wage rises to raw material price increases, the scale of the uncertainty connected to the trade war made it a “very different” challenge.

“This is a moment for the manufacturing industry to think about how to diversify risk, whether to upgrade products and add more value or expand production to other regions,” said Ms Chan, president of the Hong Kong Young Industrialists Council and chief executive of a metal production business in China.

China is by far the world’s biggest exporter of manufactured goods. But some factory owners began moving production to other developing countries such as Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam over the past decade in search of cheaper wages and a hedge against the political and economic risk that comes from reliance on one country.

Factory owners and US buyers say the trade war will intensify this shift.

When handbags were included on the proposed $200bn tariff tranche, it sent US executives scrambling to look at alternative production sites outside China.

Steve Madden, which started moving some of its handbag production from China to Cambodia three years ago, told investors recently that it was working on a plan to double its Cambodian production next year to about 30 per cent of its total, in addition to considering price rises in the US.

Michael McNamara, chief executive of Flex, which produces electronics for everyone from Bose to Google, believes it is “inevitable” that companies will reduce their reliance on China, although it will take time.

“Long term, we believe many customers will request a more regional manufacturing footprint to shorten their supply chain and reduce the risk of tariff impacts,” he said on an earnings conference call.

But unless companies have existing relationships with factories, suppliers and governments, it is difficult to jump into new developing markets where investment laws are often unclear, and labour and environmental standards lax.

Spencer Fung, chief executive of Li & Fung, which helps US retailers including Walmart and Kohl’s source their goods from factories around the world, said that while “a lot of people are desperate to move out of China”, it can take one or two years to stabilise production in a new country.

Vietnam has been at the heart of many companies’ “China plus” manufacturing strategies in recent years, attracting investments from the likes of Samsung, the South Korean electronics group, Daikin, the Japanese air conditioning group, and Techtronic.

Many apparel makers producing for fashion brands in Europe and the US have also moved from China to Vietnam. Sheng Lu, an assistant professor of fashion studies at the University of Delaware, said there were few spare workers or production facilities left. “If you’re not in Vietnam at this point, you’re probably too late,” he said.

Larry Sloven, an executive at Capstone, which sells China-made LED lighting in the US, said it was much easier to move sewing machines to a new country than to replicate the complicated network of suppliers needed in the electronics industry.

“Everybody is looking for a way to hedge but it’s not that easy,” he said. “Think about all the components that go into making an electronic product — they all come from China.”

US-China tariffs in numbers

Tariffs — and uncertainty about the direction of US-China relations — have unnerved manufacturers, but executives say China is likely to retain its dominant position.

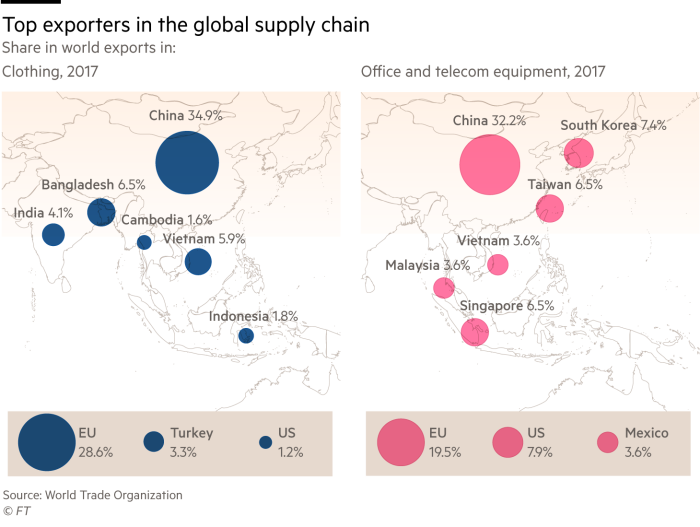

Despite losing some market share to lower-wage countries, China still accounted for 35 per cent of global clothing exports last year, compared with just 6.5 per cent from Bangladesh, 5.9 per cent from Vietnam and 1.6 per cent from Cambodia. It is in a similar position for office and telecoms equipment, according to the World Trade Organization.

Rather than fold in the face of pressure, Mr Fung said he expected Chinese factories to respond by looking for ways to boost competitiveness, from automation to developing higher value-added products.

“I don’t think if you’re a factory owner in China you will just let business go and shut the door; they’re going to start sharpening their pencils,” he said. “I don’t think you’ll see capacity reduce drastically in China.”

The Committee to Save the World Order

America’s Allies Must Step Up as America Steps Down

2018.09.30

By Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Lindsay

The order that has structured international politics since the end of World War II is fracturing. Many of the culprits are obvious. Revisionist powers, such as China and Russia, want to reshape global rules to their own advantage. Emerging powers, such as Brazil and India, embrace the perks of great-power status but shun the responsibilities that come with it. Rejectionist powers, such as Iran and North Korea, defy rules set by others. Meanwhile, international institutions, such as the UN, struggle to address problems that multiply faster than they can be resolved.

The newest culprit, however, is a surprise: the United States, the very country that championed the order’s creation. Seventy years after U.S. President Harry Truman sketched the blueprint for a rules-based international order to prevent the dog-eat-dog geopolitical competition that triggered World War II, U.S. President Donald Trump has upended it. He has raised doubts about Washington’s security commitments to its allies, challenged the fundamentals of the global trading regime, abandoned the promotion of freedom and democracy as defining features of U.S. foreign policy, and abdicated global leadership.

Trump’s hostility toward the United States’ own geopolitical invention has shocked many of Washington’s friends and allies. Their early hopes that he might abandon his campaign rhetoric once in office and embrace a more traditional foreign policy have been dashed. As Trump has jettisoned old ways of doing business, allies have worked their way through the initial stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, and depression. In the typical progression, acceptance should come next.

But the story does not have to end that way. The major allies of the United States can leverage their collective economic and military might to save the liberal world order. France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the EU in Europe; Australia, Japan, and South Korea in Asia; and Canada in North America are the obvious candidates to supply the leadership that the Trump administration will not. Together, they represent the largest economic power in the world, and their collective military capabilities are surpassed only by those of the United States. This “G-9” should have two imperatives: maintain the rules-based order in the hope that Trump’s successor will reclaim Washington’s global leadership role and lay the groundwork to make it politically possible for that to happen. This holding action will require every member of the G-9 to take on greater global responsibilities. They all are capable of doing so; they need only summon the will.

Economic cooperation is a good place to start, and G-9 members are already creating alternatives to the trade deals Trump is abandoning. But they will have to go further, increasing military cooperation and defense spending and using a variety of tools at their disposal to take over the U.S. role as the defender and promoter of democracy, freedom, and human rights across the globe. If they seize this opportunity, the G-9 countries will not just slow the erosion of an order that has served them and the world well for decades; they will also set the stage for the return of the kind of American leadership they want and that the long-term survival of the order demands. Indeed, by acting now, the G-9 will lay the basis for a more stable and enduring world order—one that is better suited to the power relations of today and tomorrow than to those of yesterday, when the United States was the undisputed global power.

The World America Made

The emergence of a rules-based order was not an inevitability but the result of deliberate choices. Looking to avoid the mistakes the United States made after World War I, Truman and his successors built an order based on collective security, open markets, and democracy. It was a radical strategy that valued cooperation over competition: countries willing to follow the lead of the United States would flourish, and as they did, so, too, would the United States.

“The world America made,” as the historian Robert Kagan has put it, was never perfect. During the Cold War, the reach of American influence was small. The United States at times ignored its own lofty rhetoric to pursue narrow interests or misguided policies. But for all its shortcomings, the postwar order was a historic success. Europe and Japan were rebuilt. The reach of freedom and democracy was extended. And with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the U.S.-led postwar order was suddenly open to all.

But that success also created new stresses. The rapid growth in the movement of goods, money, people, and ideas across borders as more countries joined the rules-based order produced new problems, such as climate change and mass migration, that national governments have struggled to handle. Economic and political power dispersed as countries such as Brazil, China, and India embraced open markets, complicating efforts to find common ground on trade, terrorism, and a host of other issues. Iran and Russia recoiled as the U.S.-led order encroached on their traditional spheres of interest. And the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the global financial crisis of 2007–8 raised doubts about the quality and direction of U.S. leadership.

Upon leaving office in 2017, U.S. President Barack Obama urged his successor to embrace the indispensability of U.S. leadership. “It’s up to us, through action and example, to sustain the international order that’s expanded steadily since the end of the Cold War, and upon which our own wealth and safety depend,” he wrote in a note he left in the Oval Office. Trump took the opposite approach. He campaigned on a platform that global leadership was the source of the United States’ problems, not a solution to them. He argued that friends and allies had played Washington for a sucker, free-riding on its military might while using multilateral trade deals to steal American jobs.

At the start of Trump’s tenure, his selection of proponents of mainstream foreign policy, such as James Mattis as secretary of defense and Rex Tillerson as secretary of state, for top national security jobs spurred hopes at home and abroad that he would temper his “America first” vision. But by withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the Paris agreement on climate change, and the Iran nuclear deal; embracing mercantilist trade policies; and continuing to question the value of NATO, Trump has shown that he said what he meant and meant what he said. He is not looking to reinvigorate the rules-based order by leading friends and allies in a common cause. They are the foes he wants to beat.

Trump’s preference for competition over cooperation reflects his belief that the United States will fare better than other countries in a world in which the strong are free to do as they will. But he fails to understand that doing better than others is not the same as doing well. In fact, he is forfeiting the many advantages the United States has derived from the world it created: the support of strong and capable allies that follow its lead, the ability to shape global rules to its advantage, and the admiration and trust that come from standing up for freedom, democracy, and human rights.

Worse, by alienating allies and embracing adversaries, Trump is providing an opening for China to rewrite the rules of the global order in its favor. “As the U.S. retreats globally, China shows up,” Jin Yinan, a top Chinese military official, gloated last year. Beijing has positioned itself as a defender of the global trading system, the environment, and international law even as it exploits trade rules, builds more coal-burning power stations, and expands its control in the South China Sea. This bid to supplant the United States as the global leader is hardly destined to succeed. China has few friends and a lengthy list of internal challenges, including an aging work force, deep regional and economic inequalities, and a potentially brittle political system. But a world with no leader and multiple competing powers poses its own dangers, as Europe’s tragic history has demonstrated. The United States will not be the only country to pay the price for a return to such a world.

The New Guard

The consequences of the United States’ abdication of global leadership have not been overlooked abroad. If anything, Trump’s policies have highlighted how much other countries have invested in the rules-based order and what they stand to lose with its collapse. “The fact that our friend and ally has come to question the very worth of its mantle of global leadership puts in sharper focus the need for the rest of us to set our own clear and sovereign course,” said Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s foreign minister, early in Trump’s presidency.

That recognition has driven repeated efforts by U.S. allies to placate Trump. They have looked for common ground despite deep substantive disagreements—not to mention Trump’s ham-handed tactics, petty insults, and unpopularity among their own citizens. But so far, these efforts to compromise haven’t worked, and they aren’t likely to for one simple reason: what U.S. allies want to save, Trump wants to upend.

The United States’ friends and allies—with the G-9 countries in the lead—need to act more ambitiously. They must focus less on how to work with Washington and more on how to work without it—and, if necessary, around it. As German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas told a Japanese audience in Tokyo last July, “If we pool our strengths . . . we can become something like ‘rule shapers,’ who design and drive an international order that the world urgently needs.”

European Council President Donald Tusk, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker at the start of a EU-Japan summit in Brussels, Belgium, July 2017

Of the potential areas for G-9 cooperation, trade holds the greatest promise, as the G-9 pulls significant economic weight and has already looked for ways to blunt Trump’s protectionist policies. The G-9 countries clearly have the capacity to push their point. Collectively, they generate one-third of global output, more than double China’s share and nearly 50 percent more than that of the United States. And they account for roughly 30 percent of global imports and exports, more than double both China’s and the United States’ share.

As important as the economic pull of the G-9 countries is the willingness they have already shown to counter Trump’s mercantilist policies. After Trump withdrew the United States from the TPP shortly after taking office, Australia, Canada, and Japan led the effort to salvage the trade deal as a counterweight to China. In early 2018, the 11 remaining members agreed on a revised pact that preserved most of the deal’s market-opening provisions; it will create a free-trade zone of 500 million people that will account for about 15 percent of global trade. Colombia, Indonesia, South Korea, and Thailand are among the nations that have expressed an interest in joining the so-called TPP-11, broadening its potential clout. The EU is also a logical partner for the TPP-11 countries. It has already negotiated separate trade agreements with Canada, Japan, and South Korea and has begun negotiating one with Australia; the EU-Japanese deal created a market of 600 million people, the largest open economic area in the world.

The TPP-11, the EU-Japanese free-trade agreement, and similar deals will intensify competition between the G-9 and the United States. The agreements give G-9 exporters an advantage over their U.S. counterparts in terms of market access and standards. But even with the growing need to work around or without the United States, the G-9 should still explore ways to cooperate with Washington. One example is the need to reform the World Trade Organization. Trump has repeatedly criticized the WTO, at times suggesting he might pull the United States out. That’s likely an empty threat, because leaving would decidedly disadvantage U.S. firms. But Washington and the G-9 share legitimate concerns about the global trading regime, particularly when it comes to China’s predatory practices. They might, for example, work to limit the sorts of subsidies that give state-owned enterprises in China and elsewhere a competitive advantage, replace the current system of “self-graduation” with objective standards for when developing countries must shoulder their full WTO obligations, and revamp the dispute-settlement process so that decisions are rendered more quickly and adhere more closely to the rules member countries have agreed on.

Cooperation Is Key

Security cooperation will be more challenging. European allies have the necessary mechanisms for cooperation through NATO and the EU, but they don’t spend sufficiently on defense. Asian allies spend more on defense, but they lack an equivalent to NATO or the EU. Yet if G-9 members can make good on commitments to invest more in their own security, the potential waiting to be tapped is impressive. The G-9 represents a military power second only to the United States. In 2017, G-9 countries together spent more than $310 billion on defense, at least a third more than what China spends and more than four times what Russia spends. Every G-9 country ranked in the top 15 of the largest military spenders in the world.

When it comes to defense, much of Trump’s criticism of U.S. allies is misguided, if not outright wrong. Despite Trump’s griping that allies don’t pay their fair share, they in fact cover a substantial part of the cost of the United States’ military presence in their countries: Germany contributes 20 percent of the cost, South Korea contributes 40 percent, and Japan pays half. What is more, the integrated command structures of U.S. and NATO forces act as a force multiplier to deliver a far bigger punch than would be possible if the United States had to act on its own. It should also not be forgotten that large numbers of allied troops have fought and died alongside Americans in Afghanistan and elsewhere.

But Trump’s complaint about free-riding allies—which several of his predecessors shared but expressed more diplomatically—has some merit with regard to both European and Asian allies. No alliance can survive if its members refuse to carry their own weight, and many U.S. allies, especially in Europe, depend too heavily on Washington for their security. They conceded as much in 2014, when every NATO member pledged to spend at least two percent of GDP on defense by 2024. Although the United States’ global security responsibilities require it to spend far more, the two percent target would still represent a significant increase for many countries and allow Europe to carry its fair share of the overall defense burden.

If all of NATO’s European members met the two percent target, their combined annual defense spending would jump from about $270 billion to $385 billion—an increase nearly twice the size of Russia’s total defense budget. An increase of that scale would allow for a major upgrade in military capabilities, especially if new funds were spent with an eye toward enhancing cooperation and connectivity among the armed forces. That is precisely the goal of the EU’s Permanent Structured Cooperation, founded earlier this year, which aims to deepen European defense cooperation. The challenge is to make sure that the aggregation of this military potential adds up to more than the sum of its parts by avoiding duplication, consolidating research-and-development expenditures, and procuring complementary military capabilities.

EU leaders on the launching of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) in Brussels, Belgium, December 2017

When it comes to military cooperation, U.S. allies in Europe have an edge over those in Asia. Asia has no equivalent to NATO and is unlikely to develop one anytime soon. U.S. allies there are, however, strengthening their defense and security cooperation in the face of China’s growing power and concerns over the reliability of the United States as a military partner. In January 2018, Australia and Japan pledged to work together more closely, including by allowing joint exercises of their armed forces. The two countries are also developing ties with India and exploring ways to conduct joint naval exercises. These early steps toward collaboration could evolve into regular planning, training, and cooperation on defense research, development, and procurement.

The lack of deep, multilateral military cooperation among Asian allies is partially offset by their willingness to invest in defense. Australia and South Korea both spend at least two percent of GDP on their militaries. Australia and New Zealand have long sent forces in support of major military operations in Afghanistan, the Middle East, and even Europe, demonstrating their belief that their own regional security is linked to security worldwide. Japan spends just one percent of GDP on defense, in accordance with its unique pacifistic constitution drafted by occupying U.S. forces after World War II. In spite of constitutional constraints, the Japanese military is one of the most capable in Asia, and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has opened an important national debate about changing the constitution and increasing the country’s military capabilities.

For the G-9 to function as a unit when it comes to security, European and Asian countries will need to collaborate more directly. Although the major European military powers are unlikely to take on a large defense role in Asia, they can and should do more. The threat posed by North Korea has long preoccupied European capitals, and European forces continue to be part of the UN command established at the onset of the Korean War. China is a major concern as well. Europe has a critical interest in ensuring freedom of navigation throughout the Asia-Pacific region and sustaining a balance of power there. Strengthening defense ties between Europe and Asia will be key to counterbalancing China’s rise. During a May 2018 visit to Sydney, French President Emmanuel Macron had this goal in mind when he called for an alliance among Australia, France, and India, saying, “If we want to be seen and respected by China as an equal partner, we must organize ourselves.”

Stepping Up

Liberal democracy has come under assault after many decades of advancing across the globe. Led by China, authoritarian countries are openly challenging global rules and ideas about freedom and making the case that their sociopolitical systems work better than liberal democracy. The rise of populist movements in many Western countries has led to increased support for illiberalism even within established democracies. A growing refugee and migration crisis is challenging liberal norms regarding tolerance and diversity. But the loss of the United States as a strong global leader is perhaps the biggest change.

For 70 years, Western allies shared a commitment to democracy, freedom, and human rights and a belief that advancing them globally was an essential contribution to international peace and prosperity. The G-9 needs to carry on this work, even if Washington bows out. It can start by taking the lead in international institutions, such as the UN and the World Bank. Washington’s voice has fallen silent in these forums. The G-9 countries must speak up loudly, clearly, and in unison in favor of democracy and freedom wherever and whenever these are challenged.

Political exhortation is unlikely to be sufficient on its own. The G-9 needs to flex its economic muscles, too. For example, it could use trade preferences and development assistance as leverage (a strategy China never shies away from). In 2017, the G-9 spent more than $80 billion on official development assistance, well over twice what the United States spent. Conditioning aid on the protection and promotion of democracy, freedom, and human rights would be a powerful way for G-9 countries to defend and extend these core values.

The G-9 will also have to use military force independent of Washington. France and the United Kingdom have already led military interventions for humanitarian purposes, mainly in northern and western Africa. In June 2018, together with seven other EU allies, the British and the French agreed to establish a joint military force to intervene in times of crisis. This is another small but important step that could serve as a model for similar collaborations.

Protecting The Order

To be effective, the G-9 will have to institutionalize in some form. Annual leader summits and regular meetings of foreign, defense, and other ministers will be needed to give the group’s efforts weight and significance. The G-9 could also form an informal caucus in international institutions, such as the UN, the WTO, and the G-20. In strengthening formal ties and cooperation, the G-9 should avoid appearing exclusive; it should at all times welcome the participation and support of like-minded countries, including the United States. The goal should be to uphold and rejuvenate the existing order, not to create a new, exclusive club.

The primary obstacle the G-9 will face, however, isn’t likely to be institutional; it will be a lack of political will to step up and defend the order. Washington has exhorted its European and Asian allies to carry more weight for years and has been met mostly with shrugs and excuses. Meanwhile, countries such as Germany and Japan have grown comfortable complaining about U.S. policy but remain unprepared to take on more responsibility. European countries have tended to look inward, and U.S. allies in Asia have preferred to deal with Washington bilaterally rather than work with one another.

U.S. allies are also tempted to avoid taking action by the hope that Trump might not actually do what he threatens or that a new president will take office in January 2021, and the storm will pass. But Trump’s first 20 months in office suggest that he believes his nationalist, unilateralist, and mercantilist policies have produced “wins” for the United States. And even if Trump serves only one term, his successor may pay a political price for trying to reclaim a global leadership role for the United States. Although recent polls by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and others have shown that the American public rejects critical parts of “America first”—support for an active U.S. role in the world, for trade deals, and for defending U.S. allies has increased markedly since Trump took office—the idea that lingering resentment toward ungrateful allies propelled Trump to victory has become conventional wisdom in some circles. Without evidence that the United States’ partners are doing their fair share, a new president may choose to remain on the sidelines of international politics and focus on domestic issues.

The G-9 must act now to prepare for such risks. Yet at the same time, it should recognize that without U.S. help, it can sustain the order for only so long. In the long run, the best the G-9 can hope to accomplish is to keep the door open for the eventual return of the United States. The challenges to the postwar order are too broad and the task of collective action too great to expect G-9 members to sustain alliances, maintain open markets, and defy democratic regression indefinitely. Unlike the United States, the G-9 consists of nine different political entities (including one that represents 28 nations), each of which faces distinct political pressures and requirements. Their ability to act in concert and to lead globally will invariably be less effective than that of a single great power.

Fortunately, “America first” need not become America’s future. Instead, it could be a productive detour that reminds Washington and its allies why the order was created in the first place. Indeed, by investing more in that order and carrying a greater share of the burdens and responsibilities of global leadership, the G-9 may not only help sustain the order but also place it on a more stable and enduring foundation. The outcome may be one many U.S. leaders have long sought—a more balanced partnership with European and Asian allies in which everyone contributes their fair share and has a say in how the order should evolve to meet the new challenges.

Allied leaders know that they need to take more action. They understand that although the demise of the liberal order will cost the United States dearly, it will cost them even more. Great-power competition will intensify, predatory trade practices will spread, and the democratic reversal already under way will pick up speed. “The times when we could completely count on others, they are over to a certain extent,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel remarked a few months after Trump came to office. “We Europeans really must take our fate into our own hands.” Now is the time for Germany and the other G-9 countries to match deeds to words. If they settle for complaints and laments, they will have more than Trump to blame for the passing of the rules-based order.

Trump is the product of a new world where voters in the U.S. feel increasingly vulnerable to influences from the outside — influences which can no longer be controlled as they were in the past.

The tools we use to manage the rest of the world are now available outside the West. When power and influence flow in all directions, the result is an order where everyone will rule and be ruled at once.