笨狼发牢骚

发发牢骚,解解闷,消消愁

正文

前两天提及一篇给中国金融、债务限制鼓起的专论(不必为中国银行担忧?),作者是彼得森国际经济研究所研究员,实属难得,果然《人民日报》没放过:

我提及是因为罕见、不简单,不过我也言及:

读读任何西方任何经济金融方面的报纸杂志网站,说起中国债务,尤其是企业债和其对中国银行的压力,不说马上崩溃,也说危机重重,中国面临的局面是前所未有,大家都无良策。比较认可的方式是短期内接受巨大损失,接受剧痛,做大幅的改革,来换取过度和长期健康稳定的发展。

国内的主要机构,保证媒体,除了《财新》说的比较值,大家要么不说,要么紧跟中央,正面为主。偶然国内财政部,尤其是央行的大头出来对外解释,因为不好说大话,谈及一些实情,大家也是三言两语带过,不带细节。

我的印象是国内企业目前的状况已经到了不能再坏的程度,再恶化的话,影响习李的地位。不过社会动乱市场崩溃的可能性是不太可能的,一旦出事儿,放下面子,也能应付的过去。

在该博文下端我也举了另外一个常住中国的西方评论员对中国的悲观看法。

今天在列举几个相关的、反面的观点。此类观点最多,这几个提意见的对中国都有一定认识。

《中参馆ChinaFile》

How Much Debt Is Too Much in China?

A ChinaFile Conversation

A ChinaFile Conversation

三位专家是美国卡内基国际和平基金会高级研究员、世界银行前中国业务局局长黄育川,保尔森基金会智库研究员宋厚泽和Derek M. Scissors,resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI)

黄育川

the argument that China is about to fall off a financial cliff is overstated

Although there are many anecdotal examples of financial stress, there is little evidence of widespread insolvency among Chinese firms and local governments that could threaten the broader economy(难说,不多,也不少)

The clearest area of concern for China is corporate debt, with the rapidly increasing size of China’s corporate debt setting it apart from other countries. But much of this surge is concentrated among a narrower subset of firms in construction and property development and in the commodity and energy sectors. The more egregious cases tend to be large SOEs which will in some cases require consolidation, mergers, and bankruptcy

Although there are many anecdotal examples of financial stress, there is little evidence of widespread insolvency among Chinese firms and local governments that could threaten the broader economy(难说,不多,也不少)

The clearest area of concern for China is corporate debt, with the rapidly increasing size of China’s corporate debt setting it apart from other countries. But much of this surge is concentrated among a narrower subset of firms in construction and property development and in the commodity and energy sectors. The more egregious cases tend to be large SOEs which will in some cases require consolidation, mergers, and bankruptcy

宋厚泽

The size of China’s debt is worrying, but what is more worrying is its composition, i.e. the percentage of debt that goes to low efficiency entities

it seems the central government doesn’t have much in debt. However, we should not overlook Beijing’s contingent liabilities. In addition to its responsibility to bail out SOEs, Beijing also fully backs the debt of China’s three national policy banks and all high-speed rail investments

参见:

《经济参考报》煤炭钢铁业万亿去杠杆博弈升级,地方私下要求银行输血

Derek M. Scissors

How much Chinese debt is too much? The amount that helps prevent painful reforms. In this light, there is already too much debt

《彭博》标普穆迪质疑地方政府集资方式

China’s Regional Funding Fix Leaves Questions for S&P, Moody’s

Direct sales of local government bonds have surged to a record 2 trillion yuan ($304 billion) since March 31, up from 906 billion yuan in the first quarter, fueled by a program to swap expensive debt for cheaper municipal securities

About 3.2 trillion yuan in bonds were issued for refinancing old debt last year with another 5 trillion yuan to 6 trillion yuan to be issued this year and in 2017

China’s Regional Funding Fix Leaves Questions for S&P, Moody’s

Direct sales of local government bonds have surged to a record 2 trillion yuan ($304 billion) since March 31, up from 906 billion yuan in the first quarter, fueled by a program to swap expensive debt for cheaper municipal securities

About 3.2 trillion yuan in bonds were issued for refinancing old debt last year with another 5 trillion yuan to 6 trillion yuan to be issued this year and in 2017

《华尔街见闻》评论:

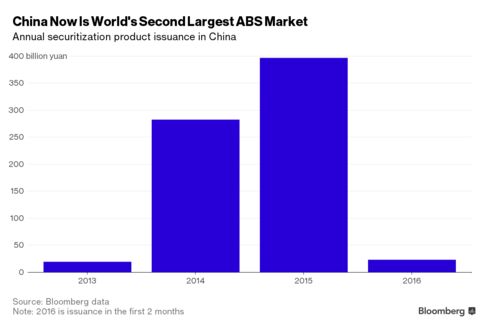

《彭博》企业债打包冷冷清清

“We don’t have enough domestic institutional investors with the expertise to price such complex products,” said Ming Ming, Beijing-based head of fixed-income research at Citic Securities Co., China’s largest brokerage. “Lack of qualified investors, especially in the junior tranche, will make it hard for banks to sell NPL-backed securities and constrain their development.”

The problem is that most Chinese insurers, trusts, brokerage firms, and mutual funds lack the expertise to invest in bonds backed by bad loans

清华金融教授裴倜斯(Michael Pettis)在清华待了多年,虽然出身于华尔街投行,说话却多引经据典,西方标准经济学、金融学理论一大堆,不过他据此对希腊中国预测多次,末日也没发生,他现在说话口气比较紧,不瞎下结论。由于他在中国扎根,又是老美,西方在中国问题上还是听他的。

最近《金融时报》举办中国问题讨论班(伦敦),裴倜斯应邀参讲,《金融时报》博客登载的一文的片段。

裴倜斯就中国现状谈起两种经济理论,说按照老路子接着投资和新政改革,都行(就是理论上都有根有据),不急下结论,老奸巨猾,呵呵。他说中国现有利益势力给改革的助力很大:

more difficult and much more likely to be virulently opposed by the elites whose ability to constrain economic efficiency is precisely at the heart of their wealth – which consists of appropriating resources rather than creating resources – and of their power

(参见李克强对利益集团。)裴倜斯话锋一转,说起十三五”规划纲要的“到2020年国内生产总值和城乡居民人均收入比2010年翻一番”,不但难,而且两者毫无同时实现的可能。

参见:

如果只是主攻总产值:

Chinese GDP between now and 2021 must grow on average by at least 6.5% annually. This probably requires that by 2021 total debt will rise to a level equal to between 360% and 540% of China’s GDP. This, to put it mildly, is implausible

所以“It makes far more sense for Beijing to focus on the other part of that same announcement. Beijing promised also to double household income between 2011 and 2021”,别管增长率。

两三年内如果转型不成功,那大限就到了:

Hovering over all of this is the question of timing: how much longer can debt continue to rise to allow Beijing to achieve its targeted growth rates? There is no science to determining the answer, but historical precedents suggest that policymakers and investors nearly always overestimate, and by a large margin, the time they have during which debt can continue to grow. My own guess is that Beijing has two to three years – perhaps four if global conditions turn very positive – but not more than that before debt levels become so high that growth grinds to a halt

参见:

《(中经网数据有限公司)中国权威经济论文文库》

实现居民人均收入翻番的难度与对策分析

刘树成 3013.04.17

摘要:

本 文首先回顾了改革开放以来我国历次翻番目标的提出过程,阐明党的十八大提出国内生产总值和居民人均收入双翻番的含义。在此基础上,分析了居民人均收入翻番 的难度,探讨了实现居民人均收入翻番的相关对策。指出提高居民收入的最根本环节是,把生产搞上去;提高居民收入的最重大举措是,抓好国民收入分配大格局的 改革和调整;提高居民收入的最基本途径是,提高劳动者报酬收入。

实现居民人均收入翻番的难度与对策分析

刘树成 3013.04.17

摘要:

本 文首先回顾了改革开放以来我国历次翻番目标的提出过程,阐明党的十八大提出国内生产总值和居民人均收入双翻番的含义。在此基础上,分析了居民人均收入翻番 的难度,探讨了实现居民人均收入翻番的相关对策。指出提高居民收入的最根本环节是,把生产搞上去;提高居民收入的最重大举措是,抓好国民收入分配大格局的 改革和调整;提高居民收入的最基本途径是,提高劳动者报酬收入。

【附录】

《财新周刊》 2016年第20期 出版日期 2016年05月23日

财新记者 岳跃

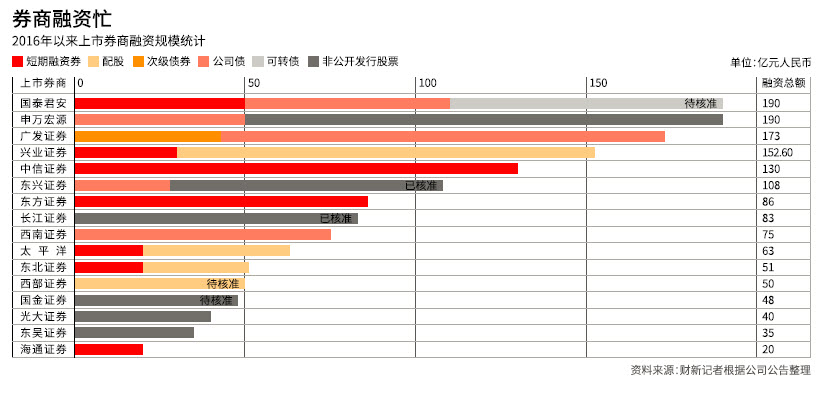

券商融资困局

定增审核趋严、风险资本准备提升,证券公司融资之路重重遇阻

因资本金不足,业务开展受限,A股上市的证券公司正多渠道加快融资步伐,2016年以来,已经完成和正在进行的融资总额近1500亿元。

券商融资困局

定增审核趋严、风险资本准备提升,证券公司融资之路重重遇阻

因资本金不足,业务开展受限,A股上市的证券公司正多渠道加快融资步伐,2016年以来,已经完成和正在进行的融资总额近1500亿元。

去年股灾之后,定增价格远高于二级市场股价,不少券商放弃此前青睐的定增方式,转而选择配股融资。年初至今,兴业证券(601377.SH)、太平洋证券(601099.SH)、东北证券(000686.SZ)通过配股共完成融资196.6亿元;西部证券(002673.SZ)配股融资50亿元的计划正在等待证监会的核准。

在一直以净资本为核心的监管体系下,券商各项业务的发展都与其资本金规模密切相关。综合多家券商发布的公告,融资的用途也大多为增加资本金、补充营运资金,以扩大业务规模。

一般来说,上市券商较多采用直接融资方式,从期限长短看,短期融资渠道主要有银行间同业拆借、发行短期融资券等,中长期融资渠道包括发行公司债、次级债、定增等。而现实情况是,短期融资行政管制因素较多、门槛较高,中长期融资渠道相对匮乏。

“充足的资金准备,意味着开展更多新业务、开拓新市场的可能,但在资金压力之下,证券公司的选择其实很有限,要么压缩传统业务规模、减少业务创新投入,要么以短期融资补长期资本不足。”一券商风控部门的人士对财新记者表示,“这都会加大券商的经营风险,资本实力和抵御风险的能力不相匹配。”

证监会今年4月8日开始就《证券公司风险控制指标管理办法》(下称《办法》)和《证券公司风险控制指标计算标准的规定》(下称《标准》)公开征求意见。市场观点称,监管层试图构建以资本管理为核心的风险管理体系,多项业务指标的调整给券商进一步带来资本压力。

截至5月中旬,24家A股上市券商4月的经营数据已经公布完毕,营业收入合计124.72亿元,环比减少46.8%;净利润合计50.80亿元,环比减少57.89%。据中国证券业协会统计,截至2016年3月31日,126家证券公司总资产为6.03万亿元,净资产为1.48万亿元,净资本为1.24万亿元。

配股成风

西部证券5月6日公告称,配股事宜已获国资委批复,同意陕西省电力建设投资开发公司(下称陕西电投)和西部信托有限公司(下称西部信托)认购可配股份。配股方案尚需获得公司股东大会审议通过,并需获得证监会的核准后方可实施。

5月10日,陕西电投及西部信托承诺,将按持股比例、以现金方式,全额认购本次配股的可配售股份。

按照此前公布的配股预案,西部证券按照每10股不超过3股的比例配售,募集资金总额不超过50亿元,具体用于信用交易的融资融券和质押式回购业务(不超过30亿元)、创新型自营业务(不超过15亿元)、资产管理业务(不超过3亿元)、信息系统建设(不超过1亿元)和其他资金安排(不超过1亿元)。

去年以来,已有四家上市券商公布配股方案,其中有三家今年已完成配股融资,合计196.6亿元。

第一家是兴业证券。今年1月5日,兴业证券配股认购缴款结束,原股东按8.19元/股的价格,以10配3比例参与配售,最终有效认购数量为14.97亿股,占可配股份总数的95.94%,共募资122.6亿元。

太平洋证券1月11日公告称,按照10配3比例向全体股东配售,配售价格为4.24元/股,募集不超过45亿元的资金投向信用、自营、资管等业务。1月21日,配股完成,实际募集资金约42.98亿元。

4月14日晚间,东北证券公告称,已按10配2比例,配售完成公司股票,配售价格为9.08元/股,募集资金约31亿元。东北证券计划在投行业务方面投入更多的资本金作为证券承销准备金,通过提高净资本水平,扩大融资融券、股指期货、股票质押式回购等创新类业务规模。

值得注意的是,东北证券在配股同时,还于3月1日完成了2016年第一期20亿元人民币短期融资券的招标。

东北证券称,尽管发行短融和短期公司债可以解决短期融资需求,“但是不能提高净资本水平,无法拓展公司业务类型、增强公司实力”,通过配股募集资金,“可以迅速提高净资本水平,扩大公司业务规模”。

此前,国信证券(002736.SZ))曾于去年6月10日向证监会提交配股申请文件,但这一方案已经中止审核。

去年11月26日,国信证券收到证监会《调查通知书》,称其涉嫌在开展融资融券业务中违反《证券公司监督管理条例》第八十四条“未按照规定与客户签订业务合同”的规定而被立案调查。根据相关行政许可程序规定,国信证券于今年1月8日向证监会申请中止审核配股,“后续将依据中国证监会立案调查结果,决定申请恢复审核或终止审核配股事项”。

“现在做配股的券商,主要都是因为资本金不够用,或者是风险控制指标达标有困难。”一位券商研究所的非银分析师对财新记者表示,“而定向增发现在是审核标准趋严、节奏变慢,券商们等不起,所以效率更高的配股成了新选择。”

“配股发行不仅是在按市价向老股东按持股比例增发新股,同时也相当于在赠送股票股利。老股东不参加配股是很吃亏的,权益会被摊薄。”一位私募基金经理说。

还有市场人士调侃道,“增发没人要才配股,增发有人要的话,还轮得到散户配股吗?”

定增受冷

今年1月21日,东吴证券(601555.SH)宣布完成定向增发,增发价为11.8元/股,发行数量为3亿股,募集资金总额35.4亿元,有限售条件流通股预计于2017年1月20日可上市流通。

值得一提的是,该单定增于去年上半年发布方案时,初始底价为增发价的2倍,23.5元/股。2015年股灾开始后,股价的急速下跌已让定增价毫无吸引力。去年8月18日,东吴证券调整定增方案,把“按照发行价格不低于定价基准日前20个交易日公司股票交易均价的90%”,改为“发行价格为不低于15.83元/股”。

此后,股灾2.0继续,指数下跌、价格倒挂,东吴证券又不得不在去年10月22日宣布再度调整定增方案,发行底价定为11.5元/股。完成定增后第一个交易日,东吴证券股价盘中曾一度跌破增发价,最终收于11.8元/股,勉强未破发。

无独有偶,申万宏源(000166.SZ)的定增也是几经周折,不仅经历了两次下调增发底价,还申请过中止审查,定增价从最初的16.92元/股降至12.30元/股,再到10.07元/股。

去年12月17日,申万宏源公告称,“由于目前市场环境发生较大变化,公司和保荐机构经审慎研究和充分论证后,向中国证监会提交了关于中止审查公司非公开发行股票申请文件的申请。”12月30日,在调整定增方案后,申万宏源向证监会报送恢复审查的申请。

今年3月30日,申万宏源这单140亿元的定增终于获得证监会发审委审核通过。

不仅如此,监管层去年以来对再融资整体收紧,上市券商也未能幸免。去年6月24日,国金证券(600109.SH)发布定增公告,预计募集不超过150亿元,后于11月10日调整方案,定增发行底价由26.85元/股下调至14.38元/股,发行最低数量由5.59亿股下调为3.34亿股,募集资金规模由150亿元下降至48亿元。

今年1月21日,国金证券收到证监会的再融资反馈意见书,要求披露各资金用途拟投入金额和其他投资安排的具体内容。

值得一提的是,国金证券曾于去年5月29日刚完成一次45亿元的定增。证监会也注意到这点,在反馈意见中称,国金证券两次募集资金之间未满12个月,且同样用于增加公司资本金、补充营运资金,要求对本次融资的必要性作出解释,是否存在募集资金数额超过项目需要量的情形。

国金证券方面回应称,前次募集资金在2015年6月30日的余额为0.10元,已基本使用完毕。也就是说,45亿元定增而来的资金,仅一个月时间就被消耗而尽。

“受到净资本规模的影响,创新业务的拓展空间将受到制约,亟须补充资本、满足创新业务发展需要。”国金证券称,“本次募集资金数额不存在超过项目需求量的情形。”

此外,财新记者此前还获悉,证监会已经叫停上市公司跨界定增,涉及互联网金融、游戏、影视、VR四个行业;同时,这四个行业的并购重组和再融资也被叫停。

国金证券的此单定增刚好“躺枪”。其定增公告称,48亿元募集资金将全部用于进一步加大对互联网证券经纪业务的投入、拓展证券资产管理业务等。其中,加大互联网证券经纪业务投入不超过6亿元。

一家投行人士此前告诉财新记者,早在今年3月,证监会就已经对上市公司跨界定增第二产业的项目进行收紧,对该类项目进行“专项核查”,但当时并未明确禁止上述四类行业的并购重组,属于“小范围”设卡,监管层希望资本市场的资金尽量流向实体经济产业。

此前还有媒体报道称,3月1日,证监会发行部口头向各家中介通知了三年期定增项目的指导意见,称三年期定增无论是否报会,若调整方案,价格只能调高不能调低,或者改为询价发行,定价基准日鼓励用发行期首日。

根据证监会发行监管部最新公布的再融资申请企业基本信息情况表,国金证券的非公开发行股票状态为“已反馈”,定增新规之下,恐生变数。

资金压力

2015年股灾之前,券商资本中介类业务火热,资金需求旺盛。根据证券业协会2014年2月发布的《证券公司流动性风险管理指引》,证券公司的流动性覆盖率(LCR)和净稳定资金率(NSFR)应达到100%。

一位大型券商的两融业务负责人当时对财新记者表示,上述两项指标对券商的融资融券业务规模有较大影响,“这两个指标对证券公司的约束比净资本约束更大,需要券商真金白银准备出优质流动资产。”在此情况下,不少券商一方面需要保有足够的优质流动性资产和长期稳定资产,一方面又需要满足业务发展对资金的需求,给风险管理带来挑战。

已经于5月8日征求完意见的《办法》和《标准》,将LCR和NSFR两项指标,由行业的自律规则上升到证监会部门规章层面,以考核券商的资产负债期限结构。

多位券商人士告诉财新记者,证券公司的风险管理总体在趋紧,“为了提升抗风险能力和争取发展更大业务规模的机会,加快融资将成为证券行业共同的选择。”

据申万宏源测算,新规将对证券公司的资管业务形成明显约束。一是根据资管业务的规模计提特定风险资本准备;二是直投、另类、创新投等子公司的投资规模,都将计入到资管业务规模中。

2015年,上市券商资管业务规模为5.9万亿元,同比增长56%;实现资管业务收入230.42亿元,同比增长119%。从资管业务结构看,定向资管计划仍是上市券商的主要业务来源。太平洋证券、西南证券(600369.SH)和申万宏源的定向资管计划规模占比均超过90%。

此外,融资类业务也会大受影响。一是新规将所有融资类业务进行统一管理。此前,证券公司风险监控指标中的融资,仅指融资融券业务的规模,但《办法》将融资融券业务、约定购回业务、股票质押式回购业务都纳入其中。二是计提融资类业务的信用风险,在风险资本准备计提中,所有融资类都要计提信用风险,这将在一定程度上增加风险资本准备。

平安证券测算,新规之下,券商融资类业务和资管业务共计需要风险资本准备4350亿元,占证券公司最新总净资本1.24万亿元的35.08%。

申万宏源证券分析师蒋健蓉表示,IPO和增发等股权融资仍是券商的首选,但受政策和市场环境影响大,次级债将成为券商债务融资的优选方式,“次级债可计入附属资本,且有利于改善流动性风险指标,不过以此方法提升净资本的额度有限。”

按照规定,证券公司次级债到期期限在三年、两年、一年以上的长期次级债,可分别按照100%、70%、50%的比例计入净资本,一年以下的不计入净资本。

广发证券(000776.SZ)5月9日公告称,已完成2016年证券公司次级债券(第一期)的发行,规模为43亿元。

“可转债也将是可供选择的优选方式,虽然属于债属性的时候无法计入净资本,但有条件转成股时就可以计入净资本。”蒋健蓉分析称,“此次征求意见稿未明确将优先股计入附属净资本的细则,但作为国外投行普遍采取的一种融资手段,以及国内优先股发行已破茧并加快发展,优先股理应成为一种可以重点发展的证券公司创新融资模式。而短期融资券、短期公司债、收益凭证等融资方式,可用以调节可用稳定资金、净稳定资金率等流动性指标。”

【纽约时报】

How China Fell Off the Miracle Path

By RUCHIR SHARMAJUNE 3, 2016

By RUCHIR SHARMAJUNE 3, 2016

(Ruchir Sharma is the chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. This essay is adapted from the forthcoming “The Rise and Fall of Nations.”)

A vendor waits for customers at a market in an urban village under demolition in Zhengzhou, Henan province, in May

FOR years now, Donald J. Trump has been sounding the alarm on China, calling it an economic bully that has been “eating our lunch.” The crux of Mr. Trump’s attack is that Beijing manipulates its currency to keep it cheap and give Chinese exports an unfair advantage. But that narrative is so last decade. China is now a threat to the United States not because it is strong but because it is fragile.

Four key forces have been shaping the rise and fall of nations since the 2008 financial crisis, and none of them bode well for China. Debts have risen dangerously fast in the emerging world, especially in China. Trade growth has collapsed everywhere, a sharp blow to leading exporters, again led by China. Many countries are reverting to autocratic rule in an effort to fight the global slowdown, none more self-destructively than China. And, for reasons unrelated to the 2008 collapse, growth in the world’s working-age population is slowing, and turned negative last year in China, depleting the work force.

Soaring Debt

China’s total debt as a percent of G.D.P. — public and private debt, including both commercial and household — has risen sharply. Total U.S. debt has stabilized. Source: Bank for International Settlements

It will be difficult for any country to grow as rapidly as 6 percent, and all but impossible for China. Nevertheless, in an effort to exceed that target, Beijing is pumping debt into wasteful projects, and digging itself into a hole. The economy is now slowing and will decelerate further when the country is forced to reduce its debt burden, as inevitably it will be. The next step could be a deeper slowdown or even a financial crisis, which will have global repercussions because seven years of heavy stimulus have turned the world’s second largest economy into a bloated giant.

In Beijing, confidence has given way to a case of nerves. Local residents often sense trouble coming before foreign investors and are the first to flee before a crisis. Chinese moved a record $675 billion out of the country in 2015, some of it for purchases of foreign real estate. If China were eating America’s lunch, its people would not be rushing to buy safe-haven apartments in New York or San Francisco. Far from conspiring to cheapen its currency, as Mr. Trump charges, Beijing is struggling to keep the weakening renminbi from falling more, which would further erode local confidence and make a crisis more likely.

Money Talks, and Walks

Net capital flow to or from China, in billions of dollars.

Source: Institute of International Finance

The seeds of China’s current problems were planted in the months after the global economic crisis of 2008. When I visited Beijing in September of that year, just before the Wall Street implosion, the country’s economy was slowing, but the city was calm. Beijing had hosted the Summer Olympics, and in preparation had temporarily shuttered smokestack industries and eased censorship. The skies were clear, the conversation much more candid than it is today.

The nation had good reason to feel confident. Like Japan, South Korea and other Asian “miracle” economies, China had generated a long run of double-digit growth by investing in export industries. But Wen Jiabao, then prime minister, was not complacent. He was warning that after three decades of heavy industrialization, China was “unstable” and “unbalanced,” with too many factories belching too much smog. Many prominent Chinese recognized that with per-capita income rising above $8,000, their nation would face a natural slowdown, as Japan and South Korea had when they reached a similar middle-income level. Meanwhile, among outsiders, there was hopeful talk of how China would evolve into a democracy as it grew richer — again following the path of earlier Asian miracles.

Then, two weeks after I left, Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in the United States, tipping the global economy into recession. Demand collapsed across the world, crushing export growth in China. The leadership in Beijing panicked, apparently fearing that if the recession reached its shores, social unrest would follow. Mr. Wen reversed course and doubled down on the old industrial model — fueling investment in factories with trillions in state lending and spending.

At first, the bet appeared to work. In 2009, China managed once again to beat its longstanding growth target of 8 percent, as the West struggled to recover from its deep recession. The rapid spending unleashed by Beijing contrasted sharply with the relative gridlock in Washington and the global elite, gathering for their annual confab in Davos, Switzerland, in 2011, marveled at the benefits of state capitalism. China, they said, was proving that unchecked autocracies had an advantage in managing the economy, particularly in a crisis.

But looking back, we can see that this was the moment China began to fall off the miracle path.

A Rising Currency, a Less Competitive China

As the renminbi becomes more valuable, China’s exports get more expensive. Percent change in the real effective exchange rate since 2003.

Under pressure from trading partners, China announced in July 2005 that it would not peg its currency to the dollar, allowing the renminbi to rise in value.

2016 figures through April 30.

Source: Morgan Stanley Investment Management analysis of data from the Bank for International Settlements and the International Monetary Fund

As its debt mania progressed, more of the lending was diverted into wasteful speculation. Normally, frenzied borrowing occurs amid excitement about a new innovation like the internet. But this spree spread on conviction that Beijing, obsessed with hitting its growth target, would not let lenders or borrowers fail. More and more unqualified players got in the game. The state banks soon had to compete with “shadow banks,” including crowdfunding websites that offered ordinary people a chance to invest in debt for as little as one renminbi (15 cents), promising fantastic returns.

Try as the Chinese authorities might to steer the money into industry, they could never fully commit to stopping shadow banks from financing an increasingly questionable array of borrowers speculating in real estate. When I visited Shanghai in August 2010, I was stunned to see apartment blocks rising two to three rows deep all along the 110-mile route to Hangzhou. Many of the biggest debtors are front companies set up by local governments to evade national regulators. Small cities are borrowing to build futuristic museums, aquatic centers and apartment blocks that exceed local demand and are often as empty as ghost towns.

My research shows that during the 30 worst debt manias of the past 50 years, private debt — which in China is often held by local governments — rose over five years by at least 40 percentage points as a share of gross domestic product. In all 30 cases, the economy slowed sharply, typically by more than half, in the next five years.

China’s mania is now the largest ever in the postwar emerging world. After holding steady at around 150 percent of G.D.P. for much of the boom, China’s public and private debts surged after Mr. Wen’s about face in 2008, rising to 230 percent of G.D.P. by 2014. That 80-percentage-point increase is also more than three times the increase in the United States before its bubble collapsed in 2008. Since then, United States debt has held steady as a share of its economy. Though many Americans still think the nation is drowning in debt, its burden is much less worrisome than China’s because it is not growing.

Paradoxically, the authoritarian form of government that helped guide China to those years of economic growth may now be undermining its economic stability. My research suggests that compared with democracies, autocracies generate far more unstable growth, and that’s the risk in China now. Looking at the available records going back to 1950 shows that extreme swings between fast and slow growth are much more common under autocratic regimes. On a list of 36 countries that have been whipsawed between rapid growth and recession throughout the postwar era, three out of four were autocracies.

Because these governments face no check on their powers, they can force feed periods of strong growth. But they can also veer off in the wrong direction with no one to set them straight. In the early stages of China’s boom under Deng Xiaoping, Beijing did what authoritarian governments do best, suppressing opposition to breakneck development, steering the people’s savings toward building export factories and commandeering land to build the roads and bridges to bring the manufactured goods to market. But the same decision-making process, centralized in a small circle in Beijing, allowed the government to impulsively shift course in 2008 and push through the lending campaign that put China on the increasingly unstable path of more debt, and less growth.

A Future Labor Shortage

Year-over-year percent change in the working-age population (ages 15-64).

Source: United Nations

ON my recent trips to China, I keep looking for Beijing to snap back to reality, but in vain. As the economy grows more unstable, the authorities have tried to control the business cycle with an increasingly heavy hand that extends into its financial markets. In late 2014, hoping to give its struggling companies a new lift, Beijing began to praise buying stocks as a patriotic act. Millions of ordinary Chinese signed up to play the market for the first time, many unaided by a high school degree, and started borrowing to buy shares as prices rose. When the bubble burst last June, Beijing did not let it implode, as it had in 2008. It ordered people not to sell or even to speak critically of stocks. The market collapsed anyway.

Afterward the Davos crowd finally started to question whether Beijing could simply command its economy to grow. It looked as if the lesson might be learned in China, too, but when I visited this April, authorities had begun a new stimulus campaign, and debt was still growing three times faster than the economy. Against this backdrop, residents spoke of dizzying price rises in Shanghai and Beijing real estate and in obscure markets like steel rebar futures. Their intention was to keep dancing until the borrowed money stopped flowing.

The sputtering global economy is one shock away from slipping into recession. In the postwar period, every previous global recession started with a downturn in the United States, but the next one is likely to begin with a shock in China. Through heavy stimulus, China was the largest contributor to global growth this decade, but it is fragile. China’s miracle growth period is over, and it now faces the curse of debt.

评论

目前还没有任何评论

登录后才可评论.