笨狼发牢骚

发发牢骚,解解闷,消消愁

正文

《美国大众电视台》美国是世界电子垃圾最大的倾倒者

乔姆斯基

Chomsky & Krauss: An Origins Project Dialogue

上

下

Noam Chomsky and Marvin Minsky on the History of Artificial Intelligence

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/some-66-million-americans-have-zero-emergency-savings-2016-06-21

美国社会的权力结构

拥枪的权力,后果和现状

入狱率,警察和狱监工会的势力

申辩的权力和现实,金钱与平等的关系;律师协会的势力

禁毒和种族:两大渊源;严打和怜悯;执法与和谐

《HuffPost》The Vultures’ Vultures: How A New Hedge-Fund Strategy Is Corrupting Washington

Shapiro, it turns out, is but one foot soldier in the hedge fund infantry

Shapiro, it turns out, is but one foot soldier in the hedge fund infantry

“权威人士”是谁?

《华尔街见闻》

一年内刷了三次屏 “权威人士”究竟是谁?

《第一财经与阿里巴巴旗下的DT财经》

“权威人士”又发话了,党报署名到底有何玄机?

《环球老虎》

经济是“L”型,但股市是“”型

《德国之声》

5月9日,人民日报再次刊登由“权威人士”对中国经济的采访。前两次“权威人士”接受采访之后,A股都进入了调整,这次“似乎”也不例外。那么这位“权威人士”究竟是什么来历?

"权威人士"再现身 中国铁心"去杠杆"?

《北京电视台》

媒体揭秘:被人民日报刷屏"权威人士"是谁

《晓帆专栏》权威人士到底是谁?能当反向指标么?

“权威人士平时喜欢吃庆丰包子铺的包子”,呵呵,习近平,跟我一个想法

《人民日报》

开局首季问大势——权威人士谈当前中国经济

本报记者 龚雯 许志峰 吴秋余

一年内刷了三次屏 “权威人士”究竟是谁?

《第一财经与阿里巴巴旗下的DT财经》

“权威人士”又发话了,党报署名到底有何玄机?

《环球老虎》

经济是“L”型,但股市是“”型

《德国之声》

5月9日,人民日报再次刊登由“权威人士”对中国经济的采访。前两次“权威人士”接受采访之后,A股都进入了调整,这次“似乎”也不例外。那么这位“权威人士”究竟是什么来历?

"权威人士"再现身 中国铁心"去杠杆"?

《北京电视台》

媒体揭秘:被人民日报刷屏"权威人士"是谁

《晓帆专栏》权威人士到底是谁?能当反向指标么?

“权威人士平时喜欢吃庆丰包子铺的包子”,呵呵,习近平,跟我一个想法

《人民日报》

开局首季问大势——权威人士谈当前中国经济

本报记者 龚雯 许志峰 吴秋余

解读(华尔街见闻):

最全解读:关于权威人士的谈话 你只需要明白这七点

权威人士解读“股市、汇市、楼市”政策取向:不能加杠杆硬推经济增长

管清友解读“权威人士谈话”:股市汇市楼市各归其位

最全解读:关于权威人士的谈话 你只需要明白这七点

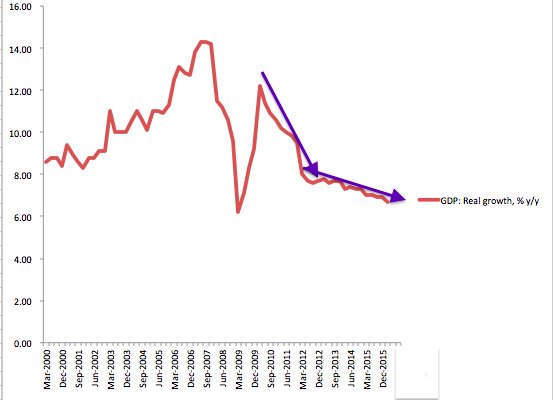

1、确认经济L型,供给侧改革回归政策重心

2、反对高杠杆硬推经济

3、严防金融高杠杆

4、股市汇市涨跌不再是政策目标

5、否定用房地产加杠杆来去库存

6、强调预期管理

7、去产能:保人不保企

权威人士解读“股市、汇市、楼市”政策取向:不能加杠杆硬推经济增长

管清友解读“权威人士谈话”:股市汇市楼市各归其位

最全解读:关于权威人士的谈话 你只需要明白这七点

1、确认经济L型,供给侧改革回归政策重心

2、反对高杠杆硬推经济

3、严防金融高杠杆

4、股市汇市涨跌不再是政策目标

5、否定用房地产加杠杆来去库存

6、强调预期管理

7、去产能:保人不保企

1,“新动力还挑不起大梁。”

2,资源大省要丢掉幻想,不要做梦

3,政策“重点、节奏、力度”出了问题,方向没有问题

4,一季度增长付出了很大代价

5,行政手段还是要用

6,对问题不能视而不见,甚至文过饰非,否则会挫伤信心、破坏预期。

7,密切关注价格变化。

2,资源大省要丢掉幻想,不要做梦

3,政策“重点、节奏、力度”出了问题,方向没有问题

4,一季度增长付出了很大代价

5,行政手段还是要用

6,对问题不能视而不见,甚至文过饰非,否则会挫伤信心、破坏预期。

7,密切关注价格变化。

第一, 专访代表着中央高层对于经济形势的权威定调。

第二, 为什么专访大段强调 L 型?因为 L 型意味着刺激一没空间,二没必要。

第三, 专访将目前企稳界定为“老办法”,这意味着当前引擎不可持续,还是要回归结构调整,供给侧改革还是要挑大梁。

第四, 通胀还是通缩也不要争了,专访认为目前难以定论; 但对于货币宽松的幻想,专访明确标了休止符。

第五,专访将应对经济下行压力和避免实体高杠杆界定为“两难”,且暗示如果不可兼得,那么要选择后者。

第六, 八大风险点+高杠杆是原罪,后续可能会有一系列排雷措施。

第七, 明确否定楼市“通过加杠杆去库存”的做法,如果后续经济能继续企稳,楼市政策可能会进一步收紧。

第八, 市场可能部分误读了“429”政治局会议,关于股市提法的大背景是各回各位。

第二, 为什么专访大段强调 L 型?因为 L 型意味着刺激一没空间,二没必要。

第三, 专访将目前企稳界定为“老办法”,这意味着当前引擎不可持续,还是要回归结构调整,供给侧改革还是要挑大梁。

第四, 通胀还是通缩也不要争了,专访认为目前难以定论; 但对于货币宽松的幻想,专访明确标了休止符。

第五,专访将应对经济下行压力和避免实体高杠杆界定为“两难”,且暗示如果不可兼得,那么要选择后者。

第六, 八大风险点+高杠杆是原罪,后续可能会有一系列排雷措施。

第七, 明确否定楼市“通过加杠杆去库存”的做法,如果后续经济能继续企稳,楼市政策可能会进一步收紧。

第八, 市场可能部分误读了“429”政治局会议,关于股市提法的大背景是各回各位。

《南华早报》谁是人民日报的权威人士?

“在许多方面,该人士的意见都与李克强总理领导下的国务院政策相违,对许多中国官员此前发表的意见也进行了反驳”,这内幕,

“在许多方面,该人士的意见都与李克强总理领导下的国务院政策相违,对许多中国官员此前发表的意见也进行了反驳”,这内幕,

【法广RFI】

“昨天,本台记者从熟悉北京政情人士得知,此文是习近平办公室和中央财经领导小组办公室共同撰写,代表了中南海南院(党中央)观点。”

《多维综合》反驳李克强 中共党报的权威人士是他?

“国家主席习近平的首席经济智囊刘鹤或符合“权威人士"身份。刘鹤现为中共中央财经领导小组办公室主任,也是发改委副主任。”

《彭博》

China's 'Authoritative' Warning on Debt: People's Daily Excerpts

Even China's Party Mouthpiece Is Warning About Debt

China's Anonymous Economic Oracle Signals Shift From Debt

Even China's Party Mouthpiece Is Warning About Debt

China's Anonymous Economic Oracle Signals Shift From Debt

中金在线: “谋杀”A股的真凶找到了!原来是“他”↓

《英国卫报》Offshore finance: more than $12tn siphoned out of emerging countries

《兽色日报Daily Beast》How the Kleptocrats’ $12 Trillion Heist Helps Keep Most of the World Impoverished

作者网博:More than $12 trillion stuffed offshore, from developing countries alone

《兽色日报Daily Beast》How the Kleptocrats’ $12 Trillion Heist Helps Keep Most of the World Impoverished

作者网博:More than $12 trillion stuffed offshore, from developing countries alone

美国就业

《华尔街日报》

美国小业主行会叫NFIB(National Federation of Small Business)

《联储论文》

《环球老虎》2015.11.23

2016全球经济投资报告

本报告中参照IMF、OECD、WB等机构年度展望报告的行文范式,以国别来分章节,对资本市场最为关注的经济和政策变量进行分析,并以专栏形式对若干比较有意思的话题进行单独探讨。涉及到的关键点包括:经济增长、投资、消费、贸易、通胀、大宗商品、货币政策与货币政策8个方面。既包括2015年全球经济的全景式回顾,也包括2016年全球经济的前瞻。

本报告中参照IMF、OECD、WB等机构年度展望报告的行文范式,以国别来分章节,对资本市场最为关注的经济和政策变量进行分析,并以专栏形式对若干比较有意思的话题进行单独探讨。涉及到的关键点包括:经济增长、投资、消费、贸易、通胀、大宗商品、货币政策与货币政策8个方面。既包括2015年全球经济的全景式回顾,也包括2016年全球经济的前瞻。

难怪“权威人士”要出来清场

普通人的理财越来越活跃,以前较为激进的半年期保本理财产品(年化6%)现在已经是最低配置了,连大妈都不存定期了。过去非法的地下钱庄,如今摇身一变成了P2P网络基金,往往给出三个月年化率12%的产品更凶恶的有三个月15%+的,虽然谁都知道有风险,但是80后们趋之若鹜,利滚利真的很爽。当然这次股灾后两三个月,估计有人会哭昏在厕所。再往上就是基金和股市,各个银行网点每天的基金理财业务比窗口现金业务火爆的多,我办个网银签个手续1个小时,见到三个大妈和经理研究股指期货的衍生品,最少的一个投了30万。普通股民里面,敢用杠杆的越来越多,所以这回跳楼的多。但是现在,大家的思路就是大赌大赢。股票再往上一级,就是合作投资,适用于有几十万闲钱的家庭,一人牵头几家入股,各种儿童项目,老人项目是投资最火的领域,在大城市里收益很稳定。

番外带一句,江浙小城市或农村地区的人胆子更大,做生意的无论大小都是一身的三角债,而且是相对于他们本身十分惊人的数额。给外人的感觉是一旦一人资金断链几十人都得遭殃,然而他们本地人的逻辑是如果挂不进这跟链条,莫说是喝汤就连骨头渣滓都没机会拣。

肯定有人会问,实体经济这么不景气,国人到底怎么支撑诸如就业,收入,消费这样的问题,答案就是创业!一股国家意志的创业潮。李克强经济学的标签。思路就是,既然无法解决就业市场岗位严重不足的矛盾,就把大学生和年轻人推向创业,让社会去吸纳他们,然后你败了你认栽。到处都是孵化器,甚至每所大学几乎都有自己的孵化器,融资可大可小,门槛越来越低,好一点的项目不愁天使投资人,极普通的项目拿下几百万的也不在话下,而那些看起来让人觉得无厘头的垃圾项目也可以简简单单从那些P2P里搞来高利贷,甚至都不用实名抵押。反正就是有钱,真有钱,不知道从哪来的这么多钱。举个例子,什么叫‘好项目’,某肿瘤医院院长的孙子大学毕业了,和几个同学合伙搞个app,用他爷爷的内部关系来给病患排队挂号,这个公司随便就能找人融资个百万,然后没几天被阿里健康用翻倍的价格收走。一个中等项目,几个平头百姓毕业生,找几家小饭馆,开发个app给人送外卖,也就成功创业了,过不了几天那个几十万的融资,也足够他们自行车换电驴再开个小门面的了。北美华人看了估计直接气吐血。当然很多人认为这样早晚会出事,将来会有问题,但是将来是将来,关键是今天拿到钱,用温家宝的名言就是我们相信下一代领导集体的智慧。

最后说说股市,A股从上半年的人气爆棚,到过去两周的股灾,其实是各种社会问题的缩影。为什么这次国家得救市,因为不救真的可能出事。实体经济已经完蛋操了,房地产除了北京深圳回光返照,再吹泡泡就是彻底的sb,依托IT的创业风潮,虽然能解决一些问题,但是还有大量其他行业的人挤不进去,而这些人目前维持就是靠理财,p2p和众筹投资,这三个管道不管是哪个都是打着激活民间资本鼓励创业和资金利用率的旗号来招摇的,但是最后都有相当的比例还是流进股市,因为这是唯一的快钱渠道。更差的则是连环旁氏。A股这样的暴法,三四个月后隐性的民间借贷危机就会爆发,今天哪怕没有在股市损失,几个月后自己投在p2p上的也可能血本无归。习李王这次绝壁是被玩了,而且前期的被动反应全是昏招。这回不用真金白银老老实实的托盘5天,过后矛盾一旦爆发很难收场。为什么会有今天?就是所谓的反腐,四风,始终没敢烧到银行业,金融业和保险业。这些大Boss没打才要命。再举实例,天津市商务委过去一年三个正处级出事被免职交法办,最高的涉案金额才30万,最少的一个倒霉蛋3万块丢了官。而一个普通城市银行支行的行长一年自己造成个1亿坏账跟玩一样。但是至今金融系统的人仍然在以不可思议的方式作。(黄昏网友转载网传)

不知习李能不能睡着觉?

股手凯维埃尔

热罗姆·凯维埃尔(Jérôme Kerviel)是法兴银行(Société Générale)的一名普通股市抄手。然而他却导致法兴大亏€4.9 billion($73 billion)。这是他的故事。

This is how the world’s most “successful” rogue trader operated

《纽约时报》Kerviel: Bosses Never Said a Thing

热罗姆·凯维埃尔(Jérôme Kerviel)是法兴银行(Société Générale)的一名普通股市抄手。然而他却导致法兴大亏€4.9 billion($73 billion)。这是他的故事。

This is how the world’s most “successful” rogue trader operated

《纽约时报》Kerviel: Bosses Never Said a Thing

【金融时报】

US tax havens: The new Switzerland

Kara Scannell and Vanessa Houlder

The US is a magnet for offshore wealth, notably South Dakota, which has guaranteed secrecy for family trusts

US tax havens: The new Switzerland

Kara Scannell and Vanessa Houlder

The US is a magnet for offshore wealth, notably South Dakota, which has guaranteed secrecy for family trusts

In an old discount store hugging a corner in downtown Sioux Falls, South Dakota, the heirs to the William Wrigley chewing gum fortune have an office for their family trust. So do the Carlson family, owners of the Radisson hotel chain, and the family of John Nash, the late hedge fund giant.

They are among the 40 trust companies sharing an address at 201 South Phillips Avenue, a modest, two-storey white-brick building. Inside, $80bn worth of trust assets are administered.

South Dakota is best known for its vast stretches of flat land and the Mount Rushmore monument, where the heads of four presidents are carved into the Black Hill Mountains. Its population of 858,469 ranks 46th in the country. Locals joke that it has more pheasants — about 1.5m — than people.

Yet despite its small town feel, Sioux Falls has become a magnet for the ultra-wealthy who set up trusts to protect their fortunes from taxes and future ex-spouses. Assets held in South Dakotan trusts have grown from $32.8bn in 2006 to more than $226bn in 2014, according to the state’s division of banking. The number of trust companies has jumped from 20 in 2006 to 86 this year.

The state’s role as a prairie tax haven has gained unwanted attention since the release of the Panama Papers, an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The leak of more than 11m documents from a Panamanian law firm — some of which will be put on to a public database today — has drawn attention to the anonymity that is available in the US.

After years of threatening Swiss and other foreign banks that helped Americans hide their money, the US stands accused of providing similar services for the rest of the world. “America is the new Switzerland,” says David Wilson, partner of Schellenberg Wittmer, a Swiss law firm. “In the industry we have known this for several years.”

The US has a long history of attracting funds from undisclosed foreign sources. In 2011, The Florida Bankers Association told Congress there were hundreds of billions of foreign deposits in US banks because “for more than 90 years the US government has encouraged foreigners to put their money in US banks by exempting these deposits from taxes and reporting”.

The Boston Consulting Group estimates that there is $800bn of offshore wealth in the US, nearly half of which comes from Latin America. That puts it well behind Switzerland’s $2.7tn, but it is expected to grow at nearly 6 per cent a year — faster than any rival except Hong Kong and Singapore.

Bruce Zagaris, a Washington-based lawyer at Berliner, Corcoran & Rowe, says the US offshore industry is even bigger than people realise. “I think the US is already the world’s largest offshore centre. It has done a real good job disabling competition from Swiss banks.”

The growth has been fuelled by international disclosure rules introduced in 2014 to crack down on tax havens — and adopted almost everywhere except the US, which had introduced its own regulations. But these rules have gaps that preserved the advantages of trusts such as the ones on offer in South Dakota. Rules proposed by the White House last week to force companies to disclose more information about their owners are unlikely to erode those advantages.

Trusts are able to avoid scrutiny under both US and international rules as long as the owner appoints a local trustee and a foreign “protector” to direct the trustees. South Dakotan companies actively promote the secrecy offered by opening a trust in the state.

“Many of the offshore jurisdictions are becoming less appealing for international families looking for secrecy”, says the website of the South Dakota Trust Company, one of the most prominent. “Consequently, the stability of the US combined with its modern trust laws . . . may be more appealing to many international families than an offshore trust based in a less powerful country.”

Trust leader

Even before the flurry of international interest, South Dakota’s trust industry was booming. With no personal or corporate income tax, no limit on “dynasty trusts” and strong asset protection laws — shielding assets from soon-to-be ex-spouses — South Dakota has leapt to the top of annual rankings for the trust industry. Nevada, Delaware and Alaska also compete for accounts.

South Dakota’s inviting legal environment can be traced to the ground floor of the old discount store on Phillips Avenue. Upstairs is the corner office of Pierce McDowell III, the man largely responsible for the state’s renaissance.

Mr McDowell is 58 with a mop of curly hair and a knack for storytelling. (His grandfather, Pierce, whom the family refers to as “P1”, was working at a small South Dakota bank when it was stuck up by John Dillinger’s gang during their crime spree in the 1930s.) He cycles to his office on a fat-tyred bike, even in the snow, when he isn’t flying to New York or California to see clients and advisers.

The SDTC president stresses the importance of relationships to his business’s success and says the families he serves want to protect future generations — not avoid paying taxes.

Mr McDowell has been an evangelist for South Dakota for almost 25 years. In 1993 he wrote an article for Trusts and Estates magazine. In South Dakota, he said, families could employ “the same strategy used by the Rockefellers and the Vanderbilts for generations to avoid estate tax”.

The article caught the eye of Al King, then director of Citibank’s trust division in New York, and he recruited Mr McDowell to run the bank’s South Dakota office. The combination of Mr King’s legal contacts and Mr McDowell’s local knowledge catapulted the business. In 2002 the pair struck out on their own, forming SDTC with Mr McDowell in Sioux Falls and Mr King in New York.

The firm does not manage money. They help private trusts meet state requirements, such as having someone in the state serve as a director, establishing office space and carrying out administrative work within state lines. Trust companies are required to have two board meetings a year in the state. Annual fees start at $35,000 “on the low end” and go up.

Aspects of the trust industry attracted criticism. States like New York complained about the loss of billions of dollars in business to trust-friendly states as well as the leakage of income tax, which it estimated at $150m in 2013.

Lawrence Waggoner, a law professor at the University of Michigan, condemns the dynasty trusts pioneered by states like South Dakota as a “folly”. He argues that over time they would be riven by disputes and very difficult to manage. After a few hundred years there would be tens of thousands of beneficiaries. Arranging a meeting would be impossible: even the Rose Bowl football stadium in California would not be large enough to hold them all.

Some analysts question whether the state receives enough from the benefits it provides. In the 2015 fiscal year, South Dakota collected $1.79m from trust companies. The legislature passed a $4.3bn state budget last year.

Bernie Hunhoff, a Democratic state senator, has proposed imposing a corporate income tax. “We’ve had a lot of trust legislation and a lot of money is moving into South Dakota and they’re benefiting from our tax law,” he says. “That’s one reason I thought we needed a corporate income tax.”

Taking advantage

Andy Holmes relocated from Kansas City last year to help his firm, the Great Plains Trust Company, increase its presence in South Dakota after clients, including celebrities and famous athletes, asked about the state’s benefits.

Great Plains worked with SDTC to learn the ropes, but last year leased a windowless office in a brick and glass building for its two employees. Down the hall is Maroon Trust, which manages the money of Chicago’s Pritzker family. Elsewhere on the floor is a roofing company. They share a receptionist.

Mr Holmes estimates that 90 per cent of the registered trusts in the state “are what I call shell companies where you basically have a PO box or an office and somebody will come here twice a year to have board meetings and meet regulatory requirements. But there’s nobody here with feet on the ground to serve Sioux Falls. We’re trying to take advantage of that.”

For now, the biggest challenge for the industry, Mr McDowell says, is criticism of the secrecy it can offer. “So much that has been written about this stuff appears to be so sinister,” he says. “All of these tax laws are there for a reason. It’s not about tax dodging, it’s planning.”

Bret Afdahl, director of the state’s banking division, says the requirements to qualify for a trust have increased, such as having more of a physical presence. Applicants are often turned away. “We’re the chartering authority so if we approve it and something goes wrong we own it,” he says. “From a reputational standpoint no one benefits from having something bad happen.”

There are legitimate reasons to seek secrecy, according to Roderick Balfour, founder of Virtus, a Guernsey-based trust company that opened in South Dakota in 2009. He says people have a right to privacy, especially if corruption in their home countries means their data would not be secure. Concerns are overblown, he says: “America is never going to be a Panama.”

France and other countries have introduced tough disclosure rules on trusts. In many others there are suspicions that trusts are illegally used to evade tax. Gabriel Zucman, a French economist, estimates that governments lose at least $200bn a year in evaded taxes from the $7.6tn of the world’s financial wealth that is held offshore.

The respite from new reporting rules gained by moving to the US could prove temporary. On Thursday the White House called on Congress to act on “long overdue” proposals to ensure the US is in line with international standards. This Thursday, David Cameron, the British prime minister, is hosting a summit where world leaders will be asked to sign a global declaration promising to expose corruption.

There might be big risks in using the US to hide money for illegitimate reasons. Mr Wilson likens it to “sitting in the dragon’s mouth”. One law firm that used to promote the benefits of “hiding in plain sight” says its clients are now convinced the US will adopt international standards and do not wish to be “tarnished by association”.

The appeal of moving structures to the US is that it buys time, says Peter Cotorceanu, counsel for Anaford, a Zurich law firm. Any change in US law would depend on the Republicans losing control of the House, he says. He predicts that hundreds of billions of dollars will move to the US. “Most of the money will move this year”, he says, noting that individuals in Switzerland, Hong Kong and Singapore have until the end of the year to “yank their money out”.

In South Dakota, there is a mixed reaction to the trust industry’s appeal to foreigners. “In a world where it’s very hard to hide ownership or hide assets sometimes the easiest place [is one] no one would normally think of, which is the US,” says Christopher Holtby, co-founder of the Wealth Advisors Trust Company, in Pierre, the state capital.

Since establishing an office in South Dakota in 2009, he has seen signs of change. In 2014 Trident, a Swiss trust company, opened an office in Sioux Falls, he notes. “Why is an international firm setting up in South Dakota?,” says Mr Holtby. “I don’t like that international lawyers want to come to South Dakota. Generally international lawyers never bring anything that’s simple.

“And we like simple.”

裴惕斯《华尔街日报》专栏

Michael Pettis

Given its surplus economy, a weak currency could undermine growth and incite a trade war

China’s central-bank governor, Zhou Xiaochuan, consistently denies that the country can devalue its way to faster growth, arguing that a falling yuan would harm the economy. From a purely economic point of view, Mr. Zhou is right. But that hasn’t stopped a growing number of analysts from calling for a substantially weaker currency.

The arguments in favor of devaluation are straightforward. China’s economy is slowing sharply, in part because of declining exports. After many years of current- and capital-account surpluses, the past two years have seen a large balance-of-payments deficit, and China’s central bank had to intervene heavily to support the yuan.

Developing economies usually respond in such situations by devaluing their currencies. Supporters of devaluation claim that China should do the same to regain export competitiveness and reverse capital outflows.

This comparison is mistaken. China is the world’s second-largest economy and runs the second-largest trade surplus in history. Developing economies that devalued successfully were much smaller, which made it easier for the world to absorb their export surge. They also devalued only after their overvalued currencies had caused persistently large deficits.

In contrast, the yuan is not overvalued. In fact it is undervalued, as Governor Zhou all but acknowledged in an interview with China’s financial magazine Caixin three months ago.

The current account shows why: China enjoys low unemployment and brisk wage growth. Economic activity is growing 6% to 7% while debt is growing two to three times faster. China’s trade partners, on the other hand, suffer high unemployment and can barely eke out 1% or 2% growth.

Normally China would import far more than it exports. But rather than running large deficits, China has large surpluses. While its exports declined last year, global exports declined even more. China is gaining export market share and its trade surplus is growing, neither of which suggests an overvalued currency.

To keep the yuan from falling the central bank has spent about $1 trillion of its $4 trillion in reserves. But China’s shrinking reserves are driven by net capital outflows. If money went abroad mainly because Chinese investors think foreign assets are relatively cheap, a weaker yuan would reduce capital leaving China by making foreign assets more expensive. But this isn’t the reason for the capital outflows.

Money leaves China partly to buy strategic assets, partly to hedge against rising political and financial uncertainty, and partly to reverse the notorious “arbitrage” of earlier years. From 2012 to 2014, some $1 trillion poured into China to speculate on an appreciating, higher-yielding yuan.

Chinese investors don’t care about the relative value of the yuan. Rather than restrain them, a devalued yuan might actually speed up their exit. This is what happened immediately after the change in the currency regime in August. Capital restrictions had to be tightened significantly to prevent even more money from leaving.

The main reason to oppose devaluation is that rather than boost growth, a weaker currency makes a surplus economy more precarious. Instead of changing relative prices, devaluation shifts income from consumption to savings.

In deficit countries—where savings are insufficient to fund investment—slowing growth scares off foreign inflows, causing investment to decline, which slows the economy further. By redirecting income from consumption toward savings, devaluation reduces dependence on foreign capital and keeps investment from dropping.

Surplus countries, however, don’t suffer from insufficient savings, and China’s savings are excessive. Yuan devaluation would simply reduce already-low domestic consumption and increase China’s reliance on investment and exports. This happened in Japan, where a substantially weaker yen further diminished consumption without kick-starting growth. For surplus countries, devaluation replaces sustainable demand—namely consumption—with the unsustainable demand of investment and trade surpluses.

In a global economy with growing trade tensions and weak demand, a devaluation that substantially boosts China’s trade surplus may ignite a trade war. If weak currencies only benefit much smaller economies with overvalued currencies and large current account deficits, it is hard to imagine why Beijing would risk devaluation.

The past three years have been terrible for international trade. China isn’t the only major economy suffering from weak domestic demand, but it has behaved far more responsibly than Europe and Japan, which have forced their adjustment costs onto the rest of the world. Maintaining the yuan’s value has been good for both China and the world. It wouldn’t help for Beijing to change strategy.

评论

目前还没有任何评论

登录后才可评论.