笨狼发牢骚

发发牢骚,解解闷,消消愁

正文

伊朗核谈近尾声。6月底的期限过了,延到今天(【1】,【2】,【3】,【5】),看来今天还是了不了,说是要延到周五。

完不了,是因为双方有底线(西方叫红线,“redline”),难让步;不走,还要谈,是因为几乎就成了,确实尽了,要谈下去,目前最大的难题是伊朗要立即免去所有制裁,而美国欧洲要全面监视伊朗国内一切(军事民用)设施。看看谁让步吧。

这两天媒体刚刚说起了一个新的难题,就是军禁(军事禁运)【4】,不知道这一直是个难题,还是新的,是个大难题。

【后记】据说消除军禁是伊朗提出来的新要求,中俄支持,俄国尤其强烈支持,大家猜测是为其军工打算。消除军禁是美国不会做让步的一个限制,伊朗在最后一霎那提出,大家有各种各样的猜测。

纽约时报记者MICHAEL GORDON解释美国的立场

央台美国站:

美国的综合立场:

从报道来看,美国咬得很紧,立了底线,一点儿也不让,主要原因是奥巴马在国内受攻击很大,怕稍让点儿步,不但怕下不了台,还怕国会借口不通过(解除制裁)。反观伊朗谈判团尽管言辞严厉,处处坚持原则,让步的倾向很大,往往依赖宗教领袖霍梅尼的讲话来增加筹码,也许如同西方所猜测【7】,伊朗的整个核工业跟美国冲突得不偿失。不管如何,伊朗国内的利益集团纷纷做好准备,就像是谈成了的样子。美国人不傻,见此,知道伊朗迟早要投降,就等着吧。今早伊朗推了一把,西方还是不接受(路透社),不过据说军禁是唯一的难题了。

伊朗外长扎里夫

世界上谁对美伊达成协议反得最厉害?以色列和沙特。另一个机构,是美国国会,当然可以说美国国会是听了以色列的。美国国内鹰派反的也很厉害,但不能左右局势。整过谈判过程,法国最热乎,有时比美国还硬,法国总统奥朗德还访问沙特,保证给沙特大量出售武器。奥巴马为了安抚中东“盟友”,许诺大量美国军火【12】,一石两鸟,为美国军工业赚了几百亿美元。

我几个月前做了预测:

2015.03.07美伊核谈预言

说双方会达成协议,而且中国会借此机会大肆增加在伊朗的投资,把整个伊朗市场占住。之后,中伊互有行动(【14】,【15】)。美国国际财团受国内政治因素限制,只能放过这块肥肉了,不过欧洲的就没那么含蓄了,德国公司【16】只是众多例子里面的一个(参见【13】)。

央台美国站:

为什么伊朗是中东最佳的地方?

在中东,伊朗可以说是最佳的投资环境。伊朗资源丰富(原油质量差点儿);伊朗政治军事跟整个地区相比无比稳定,像伊拉克、阿富汗、利比亚,资源再多,开采是问提(整天战火连天,连开工都成问题),运输是问题;修了路,叛军以骚扰,运也没法运。所以中国投了不少钱,干着急。

伊朗政治上的相对开放,如女性参与政治、经济和商业活动,阿拉伯第一,沙特一比整个是封建独裁制;选举投票(西方否认这是“民主”,因为选举人有挑选的嫌疑-跟香港一般,且霍梅尼大概有否决权),比中国还开放;伊朗总产值派世界29,购买力平价总产值18;伊朗人口素质高,教育不错,人均年龄低等,能保证投资有回报。伊朗军队参与经济商业较严重,但从另外一方面保证了局势稳定,对投资人有利。

伊朗人口分布:

经济上,伊朗有实力,消费能力强,有资源人力,买东西给他们,他们有钱付,不难想象以后伊朗取代沙特的时代。

中国投资机会

如Kevjn Lim【17】说,“China views Iran as a central element in its much-touted Silk Road Economic Belt, which aims to extend Beijing's influence overland through Central Asia to the Persian Gulf and Europe”,反之,伊朗觉得中国是跟美国争斗中难得的盟友,“During Iran's withering eight-year war with Iraq, Beijing was the only major power to supply Tehran with arms (though it did the same for Baghdad)”【中国还有双吃的时候】,伊朗的核工业是中国帮出来的(呵呵)。

央台美国站:

如果谈成,最大的得益者是中国。即使伊朗受点委屈,对中国有利无害,因为反而加强了伊朗对美国西方的怨恨,更依赖靠近中国(俄国)。伊朗大幅提高产油量会压低油价,对中国也有利。不过,中国应当意思到,世界百姓还是向往西方的生活方式,“自由上进,精神物质双享受”,据说伊朗年轻还是被美国生活方式吸引,没听说过中国的生活方式是谁追求的,所以在具体的交往上得尊重伊朗人的意愿,同时追求自己最大的利益,达到中国所谓的“双赢”。同时,伊朗经济多为军方垄断,跟民意未必相符,中国企业也得小心。总之能帮助伊朗成为经济军事上独立的国家,一对抗外来势力的欺负,符合伊朗的利益。

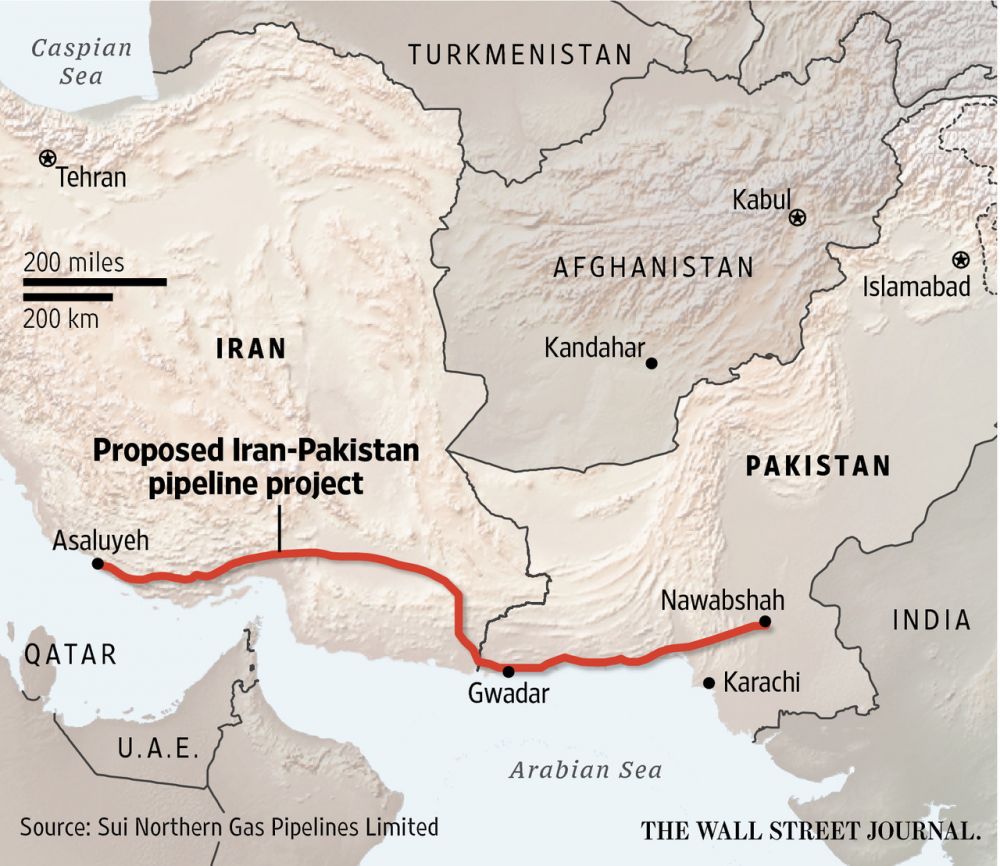

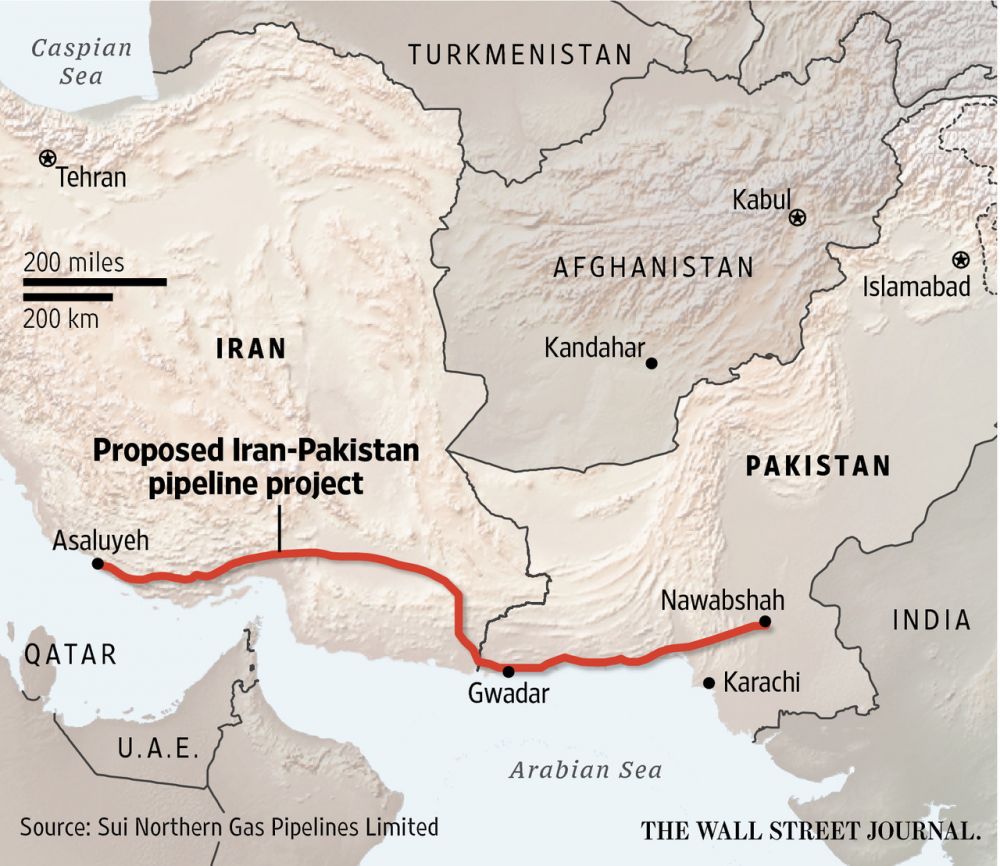

伊朗油管:最终至中国

今年4月美国新闻工作者梅查理采访伊朗外长扎里夫。扎里夫能言善辩,不缺情理,不过西方和伊朗观念差距太大,算是给聋子说了。故此可以理解为何伊朗会跟中俄接近。

譬如扎里夫指出以色列拥有近200枚原子弹(比中国还多),然而美国缄口不提。

一旦和伊朗建成牢固的盟国关系,将对中国在中东建立了一个稳定的基地,即可对中东最补给,也可以成为西进欧洲的另一条通道的立脚点。

伊朗

伊核谈判

真是千载难逢的机会,不知中国外交部在这过程中学到了什么

如果谁学到了整套过程,就是外交部长的人选。王毅要是没派个大团去,就是没脑子了

欧洲是准备要大吃一把了,中国有机会,不能放过这一机会。

【1】《英国广播公司》克里称伊朗需在核谈判中做出“艰难选择”

【2】中国外长王毅:伊朗核谈判已经有了新的进展

【3】伊朗消息人士:伊核谈判或将持续至7月9日

【4】New sticking point in nuclear talks: Iran wants arms embargo lifted

【5】美媒:美伊核谈评论

【6】What it really takes for a US-Iran deal

Pepe Escobar is the roving correspondent for Asia Times/Hong Kong, an analyst for RT and TomDispatch, and a frequent contributor to websites and radio shows ranging from the US to East Asia.

July 01, 2015

【7】Iran's nuclear program may have cost the country $500 billion or more

《路透社》

【8】 Iranian nuclear deal set to make hardline Revolutionary Guards richer

【9】U.S. and Iran: the unbearable awkwardness of defending your enemy(哪有这事儿)

《华尔街日报》

【10】Iran’s Giant Super-Tanker Fleet Eyes Western Waters

【11】Iran Wants to Double Oil Exports After Sanctions Lifted

【12】我说奥巴马就为卖军火,纽约时报也说,其它媒体怎么说?

【13】2015.04.07伊朗解禁,中国准备好了吗?

【14】2015.04.07走东方“捷径” 伊朗官员访华促石油出口

【15】2015.04.08”中国伊朗高层互访:增加对华石油出口 推动“一带一路”

这是最新的:

【16】《路透社》2015.07.05German exporters eye lucrative deals in post-sanctions Iran

【17】Iran Seen from Beijing

【附录:报道分析全文】

《华尔街日报》

【伊朗国企暗示伊朗投降?】

Iran’s Giant Super-Tanker Fleet Eyes Western Waters

Iranian shipping company NITC says its in talks with U.K. marine insurers

TEHRAN—Iran’s biggest oil shipping company has amassed the world’s largest fleet of super tankers and is in talks to sail back into western waters should the Islamic Republic strike a nuclear deal, according to senior officials.

NITC, the privatized Iranian shipping company, says it has 42 very large crude carriers, known as VLCCs, after buying 20 such China-built vessels in the past 2½ years. It is the first time the company has disclosed the size of its VLCC fleet which it expanded as sanctions cut off access to European-insured vessels,

“No other company in the world owns that number of VLCCs,” said Capt. Nasrollah Sardashti, NITC’s commercial director, in an interview in the Iranian capital. VLCCs can carry 2 million barrels of oil each.

NITC’s biggest rivals all list fewer ships, and one London-based analyst who tracks oil-tanker fleets, said he also believes NITC has the largest fleet. Competitors such as Mitsui O.S.K Lines and Nippon Yusen Kaisha of Japan and Belgium’s Euronav NV all confirmed owning fewer. No one could be reached at the National Shipping Company of Saudi Arabia, but the company says on its website that it owns 31 super tankers.

Iran was forced to rely more on NITC, the former state-owned shipping company, to transport crude oil after Europe imposed sanctions on Iran and banned insurers from covering ships carrying the Iranian crude.

U.S. and European sanctions took a toll on Iran’s exports, cutting them in half since 2012. But Iran still had buyers in Asian countries like China and South Korea, where NITC ships carried oil.

‘No other company in the world owns that number of VLCCs’

—Nasrollah Sardashti, NITC’s commercial director

As Iran and world powers close in on a deal that would lift sanctions in exchange for curbs on its nuclear program, Tehran has been seeking to build ties with European companies that have traditionally traded with the Persian Gulf country.

Ali Akbar Safaei, the managing director of the NITC, said in an interview that the company is in talks with insurance companies that are part of London’s International Group of P&I Clubs—a form of oil-shipping insurance coverage that pools insurers’ resources to cover high risks—as the company seeks to speed up its return to Europe.

“We have resumed our connections with partners in the maritime field” in the EU, he said. “All conditions are there to call at European ports” when sanctions are lifted.

‘We have resumed our connections with [EU] partners in the maritime field... All conditions are there to call at European ports [when sanctions are lifted].’

—NITC Managing Director Ali Akbar Safaei

Mr. Safaei also mentioned contacts with European safety-rating agencies, shipping logistics agencies and finance houses.

In addition to industrywide sanctions on Iran’s oil industry, the EU also banned dealings with NITC, though a European court deemed the decision illegal and “unreasonable” last year. But the EU subsequently reinstated sanctions against the company.

Mr. Safaei said a team of experts working for the company is now assessing the monetary value of the losses caused by sanctions and “then we will decide the course of action.”

【11】

Iran Wants to Double Oil Exports After Sanctions Lifted

Exports could hit 2.3 million barrels a day, deputy oil minister Moazami says

July 5, 2015

In this file photo from December 2014, an Iranian oil worker rides his bicycle at an oil refinery south of the capital Tehran

TEHRAN—Iran wants to double its crude exports soon after sanctions are lifted and is pushing other members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries to renew the cartel’s quota system, a top Iranian official said.

Both developments could set up a clash with Saudi Arabia, which is scrambling to raise its own export numbers and has opposed the return of production limits on individual OPEC members.

Iran’s efforts underscore how the country’s full return to the export market would upend the status quo among leading producers if Tehran clinches a deal with six world powers that would lift sanctions in exchange for curbs on its nuclear activities.

The latest deadline for a deal is Tuesday and officials said the elements of an agreement were falling into place over the weekend, though there were still important sticking points that could scuttle it.

Should sanctions be lifted, Iran’s deputy oil minister for planning and supervision, Mansour Moazami, said in an interview that his country’s oil exports would reach 2.3 million barrels, compared with around 1.2 million barrels a day today.

“We are like a pilot on the runway ready to take off. This is how the whole country is right now,” he said.

Iran is already in contact with former oil buyers in the European Union—traders such as Vitol Group and big oil producers such as Royal Dutch Shell PLC, Total SA and Eni SpA—as well as existing importers in Asia to help absorb the potential new shipments or invest in new fields if sanctions are lifted, according to the oil ministry and the companies.

Iran’s oil reserves are the fourth-largest in the world and its production capacity stands at about four million barrels a day—making it the second-biggest producer in OPEC if its output were unrestricted.

EU sanctions in 2012 banned the import of Iranian oil and prohibited most big oil companies from working with Iran, while American pressure forced Asian nations to reduce purchases.

The return of Iran’s oil would come at a sensitive time for the world’s oil markets.

The price of Brent crude, the global benchmark, has fallen by more than 45% in the past year, trading at around $61 a barrel, as supply outpaces demand by about two million barrels on any given day.

OPEC nations, especially Iraq and Saudi Arabia, have been pumping at record levels while production in the U.S.—a non-OPEC country—has shown signs of resilience.

Oil-market analysts have expressed skepticism that Iran could increase production as quickly as it says it will.

A senior OPEC delegate said some rival producers doubted Iran has the production and export facilities to reach its previous production levels of 4.2 million barrels a day.

Dr. Moazami said he didn’t expect prices to fall because global economic growth would drive demand higher. He said Iran’s own forecast for oil prices is now $70 a barrel by the end of 2015.

Dr. Moazami said Iran was pushing OPEC to return to individual production allocations or quotas. OPEC discontinued quotas in 2011 because they caused friction and member countries didn’t respect them anyway.

It replaced quotas with a collective ceiling—currently at 30 million barrels a day. But even that is seen as more of a guideline than a limit these days, OPEC officials have said, as the group is currently producing more than 31 million barrels a day.

Restoring quotes would need unanimous approval by the organization, something that is unlikely at this stage given the Saudi opposition.

“Their mechanism right now is not proper. It has to return to its past ability and capacity,” Dr. Moazami said of OPEC.

At its last meeting on June 5, Iran’s oil minister Bijan Zanganeh informed other OPEC ministers his country’s production would increase if sanctions are lifted and offered to reinstate the quotas.

But the proposal was brushed off by his Saudi counterpart, Ali al-Naimi, who said the output boost shouldn’t be discussed until it materializes and ruled out the return of production allocations, according to Gulf Arab and Iranian officials.

The senior OPEC official said the organization would return to quotas only if it “is absolutely necessary” and the recent price crash didn’t warrant such a decision.

【17】

《Washington Institute》

Iran Seen from Beijing

Kevjn Lim June 11, 2015

China views Iran as a central element in its much-touted Silk Road Economic Belt, which aims to extend Beijing's influence overland through Central Asia to the Persian Gulf and Europe.

Although China has long been Iran's largest oil customer, international sanctions recently relegated the Islamic Republic from third to sixth place among Beijing's suppliers -- a list consistently topped by Iranian rival Saudi Arabia. Similarly, while China's bilateral trade with Iran reportedly expanded to around $50 billion by late 2014, it remains dwarfed nearly elevenfold by its trade with the United States.

Given these figures, why does Iran play a seemingly disproportionate role in Beijing's regional calculus, often to the puzzlement of its much larger energy and trade partners in Riyadh and Washington? Diplomatic brinksmanship aside, much of the answer lies in Iran's geostrategic value as a key hub in China's westward overland thrust, which Beijing views as essential to countering both Washington's eastward pivot and U.S. naval superiority.

BACKGROUND

China and Iran's durable ties stretch back as far as the Han and Parthian empires, when the two civilizations were trade partners on the ancient Silk Road. When the Arabs invaded Iranshahr in the seventh century, Peroz III, scion of the swansong Sassanian monarch Yazdgird III, sought and was offered refuge in Tang China by the Emperor Gaozong. In modern times, despite substantive ideological differences, Ruhollah Khomeini and Mao Zedong instilled both countries with revolutionary legacies that rejected imperial hegemony and foreign exploitation, putting them on the same side against the U.S.-led status quo.

Over time, China has become Iran's least unreliable -- not to say most reliable -- major power ally and a key pivot for counterbalancing the United States. During Iran's withering eight-year war with Iraq, Beijing was the only major power to supply Tehran with arms (though it did the same for Baghdad). And in 1985, the two governments signed a stealth nuclear cooperation deal during a visit by then parliamentary speaker Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. Cooperation went from strength to strength until 1997, when U.S. pressure over the previous year's Taiwan Strait crisis spurred China to suspend nuclear and missile assistance to Tehran. By then, however, years of Chinese and North Korean technical assistance had already helped Iran establish a homegrown missile production industry, a key pillar of its defense posture.

On the economic front, Beijing has reduced its oil imports from Iran in recent years to preserve the U.S. sanctions waivers it enjoys. Owing to Iran's sanctions-induced reductions, however, it continues to buy half of Iran's crude exports. In addition to the lower prices Tehran is offering because of sanctions, Iranian supplies matter greatly to Beijing because the Gulf's other major energy producers are U.S. partners.

EMPHASIZING THE EURASIAN HEARTLAND

China has been pushing west in the context of the Silk Road Economic Belt (Sichouzilu jingjidai) introduced by President Xi Jinping in September 2013. This "westward march" had already been advocated in 2011 by Wang Jisi(北京大学国际关系学院院长王缉思), one of the country's most lucid strategic minds, with the aim of meeting and counterbalancing President Obama's eastward pivot. Under the Xi administration, Beijing's immediate Silk Road priorities appear to be threefold:

Securing the overland flow of energy from neighboring Central Asia (and Russia) to offset the risk of maritime interdiction, especially at two sensitive waterways: the Strait of Malacca (through which 80 percent of Chinese oil transits) and the Strait of Hormuz (through which about two-fifths of its oil imports pass).

Leveraging development projects to pacify the restive but energy-rich western province of Xinjiang, where Uyghur separatists advocating the establishment of an East Turkestan state have repeatedly taken up arms against the Han Chinese.

Encouraging greater regional stability and integration by locking China's western neighbors into a zone of prosperity extending to Europe, with Beijing at its political and economic nexus.

China is the world's largest net importer of oil. Given the risks of maritime interdiction, the need for overland energy conduits is particularly important. Accordingly, two new pipelines came onstream in 2006 and late 2009. The first pumps oil mostly from Kazakhstan's northern Caspian region of Atyrau through China's Xinjiang province and toward the coast, amounting to roughly 4 percent of the 6.2 million barrels per day that China imported in 2014. The other pipeline brings natural gas mainly from the Saman-Depe field in Turkmenistan, which has been China's largest supplier since 2012. In 2013 terms, Turkmen gas accounted for about half of China's 53 billion cubic meters in annual gas imports and about a sixth of its overall gas consumption. Ashgabat plans to more than double these exports by 2020.

In accordance with the Chinese saying "if you want to prosper, first build roads" (yao xiang fu, xian xiu lu), Beijing has also been modernizing the vast network of roads and railways crisscrossing Central Asia, financing its efforts through the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Silk Road Fund. In 2012, it completed a rail line extending from Khorgos to Zhetygen, Kazakhstan, and onward to Western Russia and Europe, paralleling an existing line from Xinjiang's provincial capital of Urumqi through China's Dzungarian Gate (Alashankou) and into Kazakhstan's largest city, Almaty. This east-west corridor may eventually cleave through Iran to the Gulf. According to strategist Gao Bai, Beijing has sought to offset U.S. naval superiority by building a high-speed railway capable of projecting power from China's eastern seaboard into the Eurasian interior -- a continental hedge of sorts in the event of maritime trouble. And despite the challenges that a China-bound Eurasian order could pose to Russia, President Vladimir Putin reportedly gave Xi Jinping his blessing in October 2014 after the latter agreed to include the Trans-Siberian and BAM railways in the Silk Road Economic Belt.

IRAN'S GEOSTRATEGIC VALUE

So where does Iran fit into all this? Tehran is not a dominant actor in Central Asia, partly because of its deference to Moscow, and also because the countries in question remain wary of Iranian soft-power penetration. Even its trade with the Central Asian republics is conspicuously modest. Rather, Iran fills a geostrategic role as their most convenient non-Russian access route to open waters, and the only east-west/north-south intersection for Central Asian trade. In May 1996, Iran and Turkmenistan forged this missing link by inaugurating a 300-kilometer railway between Mashhad and Tejen. And in December 2014, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Iran inaugurated a railway from Uzen (Zhanaozen) to Gorgan and onward to Iran's Gulf ports.

Meanwhile, Turkmenistan and Iran completed a gas pipeline in 1997 linking Korpeje to Kordkuy, followed in 2010 by the Dauletabad-Serakhs-Khangiran pipeline. Turkmenistan supplies about 14 billion cubic meters of gas annually to Iran, as well as a large proportion of the country's imported electricity. Similarly, Kazakh oil sent via Caspian Sea tankers has powered Iran's hydrocarbon-deprived northern provinces, in a swap arrangement that sees Tehran selling equivalent amounts on Astana's behalf via the Persian Gulf. In addition to the shorter export pathways it offers, energy relations with Iran are tempting given Russia's long history of price extortion with its Central Asian vassals. Nevertheless, such relations have not been entirely smooth -- bureaucratic disagreements have emerged with Tehran over transit fees, fuel prices, payment methods, and the like.

For Beijing, Iran's geostrategic value is enhanced by its position astride one of China's two overland bridges to the west. The other bridge skirts the northern coast of the Caspian through Kazakhstan and southwestern Russia near the Caucasus region, but Iran arguably presents the more important route because it connects with both Europe and the Gulf. Given this continental anchor, the Islamic Republic has taken on an importance in Beijing that exceeds the size of its domestic market or its role as energy purveyor.

NEXT STEPS

If a nuclear agreement with the United States brings sanctions relief to Tehran, China will no doubt intensify its presence in Iran's economy. Likewise, it will encounter fewer obstacles in extending its road, rail, and pipeline networks through the land bridge that is the Iranian plateau. A nuclear deal could also pave the way for Iran's full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a request that has been rejected since 2008 on the grounds that Tehran is under UN sanctions. The SCO, whose full members include China, Russia, and all of the Central Asian republics except Turkmenistan, is widely perceived as a counterbalance to NATO and the United States, so Iran almost certainly regards it as an additional layer of insurance in the event of future hostilities with the West.

Against this backdrop, Washington has admittedly precious little room for maneuver. Containing both China and Iran is a surefire way to drive them together. And counteracting Iran while accommodating China -- or, more improbably, vice versa -- would leave loopholes that either could exploit. The more the White House is distracted by Persian imponderables, the less robust its "rebalancing" of resources toward Asia will be, which eminently suits Beijing. The Middle East and Iran in particular are Washington's more immediate priorities, but China represents its most important long-term foreign policy challenge. How Beijing and Tehran interact in the meantime will have significant consequences for America's grand strategy.

Kevjn Lim is an independent researcher focusing on foreign and security policy in the Middle East, where he has been based for nearly a decade.

完不了,是因为双方有底线(西方叫红线,“redline”),难让步;不走,还要谈,是因为几乎就成了,确实尽了,要谈下去,目前最大的难题是伊朗要立即免去所有制裁,而美国欧洲要全面监视伊朗国内一切(军事民用)设施。看看谁让步吧。

这两天媒体刚刚说起了一个新的难题,就是军禁(军事禁运)【4】,不知道这一直是个难题,还是新的,是个大难题。

【后记】据说消除军禁是伊朗提出来的新要求,中俄支持,俄国尤其强烈支持,大家猜测是为其军工打算。消除军禁是美国不会做让步的一个限制,伊朗在最后一霎那提出,大家有各种各样的猜测。

纽约时报记者MICHAEL GORDON解释美国的立场

央台美国站:

美国的综合立场:

从报道来看,美国咬得很紧,立了底线,一点儿也不让,主要原因是奥巴马在国内受攻击很大,怕稍让点儿步,不但怕下不了台,还怕国会借口不通过(解除制裁)。反观伊朗谈判团尽管言辞严厉,处处坚持原则,让步的倾向很大,往往依赖宗教领袖霍梅尼的讲话来增加筹码,也许如同西方所猜测【7】,伊朗的整个核工业跟美国冲突得不偿失。不管如何,伊朗国内的利益集团纷纷做好准备,就像是谈成了的样子。美国人不傻,见此,知道伊朗迟早要投降,就等着吧。今早伊朗推了一把,西方还是不接受(路透社),不过据说军禁是唯一的难题了。

伊朗外长扎里夫

世界上谁对美伊达成协议反得最厉害?以色列和沙特。另一个机构,是美国国会,当然可以说美国国会是听了以色列的。美国国内鹰派反的也很厉害,但不能左右局势。整过谈判过程,法国最热乎,有时比美国还硬,法国总统奥朗德还访问沙特,保证给沙特大量出售武器。奥巴马为了安抚中东“盟友”,许诺大量美国军火【12】,一石两鸟,为美国军工业赚了几百亿美元。

我几个月前做了预测:

2015.03.07美伊核谈预言

说双方会达成协议,而且中国会借此机会大肆增加在伊朗的投资,把整个伊朗市场占住。之后,中伊互有行动(【14】,【15】)。美国国际财团受国内政治因素限制,只能放过这块肥肉了,不过欧洲的就没那么含蓄了,德国公司【16】只是众多例子里面的一个(参见【13】)。

央台美国站:

为什么伊朗是中东最佳的地方?

在中东,伊朗可以说是最佳的投资环境。伊朗资源丰富(原油质量差点儿);伊朗政治军事跟整个地区相比无比稳定,像伊拉克、阿富汗、利比亚,资源再多,开采是问提(整天战火连天,连开工都成问题),运输是问题;修了路,叛军以骚扰,运也没法运。所以中国投了不少钱,干着急。

伊朗政治上的相对开放,如女性参与政治、经济和商业活动,阿拉伯第一,沙特一比整个是封建独裁制;选举投票(西方否认这是“民主”,因为选举人有挑选的嫌疑-跟香港一般,且霍梅尼大概有否决权),比中国还开放;伊朗总产值派世界29,购买力平价总产值18;伊朗人口素质高,教育不错,人均年龄低等,能保证投资有回报。伊朗军队参与经济商业较严重,但从另外一方面保证了局势稳定,对投资人有利。

伊朗人口分布:

经济上,伊朗有实力,消费能力强,有资源人力,买东西给他们,他们有钱付,不难想象以后伊朗取代沙特的时代。

中国投资机会

进口另外,伊朗跟西方尤其美国多方面敌对意识强烈,尽管欧洲在努力,双方制度道德文化差别大,还是有敌对。

原油、天然气、资源

农产品

出口

民用商品:市场很大

(药品有机会吗?至少医疗器械有微小的机会)

基建材料(化肥、水泥)

基建设备

大型基础工程(交通、炼油厂、发电、电力网络)

军工

中国在军工上有无可媲美的优越性。首先西方不可能卖武器给伊朗,伊朗要升级,只有中俄。中国远比俄国有优越性。俄国有中国没有的武器,如防空导弹系统,但能与中国竞争的不多,中国有全面给伊朗军备升级的能力,也是伊朗需要的。对此,伊朗要求解除军禁很关键。

俄国是军火出口大国,觉得自己有优势,这是一般的判断。不过我觉得中国也有自己的优势,不比俄国差多少。不过像弹道导弹之类的长距离进攻性武器,中国就别掺乎了。

如Kevjn Lim【17】说,“China views Iran as a central element in its much-touted Silk Road Economic Belt, which aims to extend Beijing's influence overland through Central Asia to the Persian Gulf and Europe”,反之,伊朗觉得中国是跟美国争斗中难得的盟友,“During Iran's withering eight-year war with Iraq, Beijing was the only major power to supply Tehran with arms (though it did the same for Baghdad)”【中国还有双吃的时候】,伊朗的核工业是中国帮出来的(呵呵)。

央台美国站:

如果谈成,最大的得益者是中国。即使伊朗受点委屈,对中国有利无害,因为反而加强了伊朗对美国西方的怨恨,更依赖靠近中国(俄国)。伊朗大幅提高产油量会压低油价,对中国也有利。不过,中国应当意思到,世界百姓还是向往西方的生活方式,“自由上进,精神物质双享受”,据说伊朗年轻还是被美国生活方式吸引,没听说过中国的生活方式是谁追求的,所以在具体的交往上得尊重伊朗人的意愿,同时追求自己最大的利益,达到中国所谓的“双赢”。同时,伊朗经济多为军方垄断,跟民意未必相符,中国企业也得小心。总之能帮助伊朗成为经济军事上独立的国家,一对抗外来势力的欺负,符合伊朗的利益。

伊朗油管:最终至中国

今年4月美国新闻工作者梅查理采访伊朗外长扎里夫。扎里夫能言善辩,不缺情理,不过西方和伊朗观念差距太大,算是给聋子说了。故此可以理解为何伊朗会跟中俄接近。

譬如扎里夫指出以色列拥有近200枚原子弹(比中国还多),然而美国缄口不提。

一旦和伊朗建成牢固的盟国关系,将对中国在中东建立了一个稳定的基地,即可对中东最补给,也可以成为西进欧洲的另一条通道的立脚点。

伊朗

伊核谈判

真是千载难逢的机会,不知中国外交部在这过程中学到了什么

如果谁学到了整套过程,就是外交部长的人选。王毅要是没派个大团去,就是没脑子了

欧洲是准备要大吃一把了,中国有机会,不能放过这一机会。

【1】《英国广播公司》克里称伊朗需在核谈判中做出“艰难选择”

【2】中国外长王毅:伊朗核谈判已经有了新的进展

【3】伊朗消息人士:伊核谈判或将持续至7月9日

【4】New sticking point in nuclear talks: Iran wants arms embargo lifted

【5】美媒:美伊核谈评论

【6】What it really takes for a US-Iran deal

Pepe Escobar is the roving correspondent for Asia Times/Hong Kong, an analyst for RT and TomDispatch, and a frequent contributor to websites and radio shows ranging from the US to East Asia.

July 01, 2015

【7】Iran's nuclear program may have cost the country $500 billion or more

《路透社》

【8】 Iranian nuclear deal set to make hardline Revolutionary Guards richer

【9】U.S. and Iran: the unbearable awkwardness of defending your enemy(哪有这事儿)

《华尔街日报》

【10】Iran’s Giant Super-Tanker Fleet Eyes Western Waters

【11】Iran Wants to Double Oil Exports After Sanctions Lifted

【12】我说奥巴马就为卖军火,纽约时报也说,其它媒体怎么说?

【13】2015.04.07伊朗解禁,中国准备好了吗?

【14】2015.04.07走东方“捷径” 伊朗官员访华促石油出口

【15】2015.04.08”中国伊朗高层互访:增加对华石油出口 推动“一带一路”

这是最新的:

【16】《路透社》2015.07.05German exporters eye lucrative deals in post-sanctions Iran

【17】Iran Seen from Beijing

【附录:报道分析全文】

《华尔街日报》

【伊朗国企暗示伊朗投降?】

Iran’s Giant Super-Tanker Fleet Eyes Western Waters

Iranian shipping company NITC says its in talks with U.K. marine insurers

TEHRAN—Iran’s biggest oil shipping company has amassed the world’s largest fleet of super tankers and is in talks to sail back into western waters should the Islamic Republic strike a nuclear deal, according to senior officials.

NITC, the privatized Iranian shipping company, says it has 42 very large crude carriers, known as VLCCs, after buying 20 such China-built vessels in the past 2½ years. It is the first time the company has disclosed the size of its VLCC fleet which it expanded as sanctions cut off access to European-insured vessels,

“No other company in the world owns that number of VLCCs,” said Capt. Nasrollah Sardashti, NITC’s commercial director, in an interview in the Iranian capital. VLCCs can carry 2 million barrels of oil each.

NITC’s biggest rivals all list fewer ships, and one London-based analyst who tracks oil-tanker fleets, said he also believes NITC has the largest fleet. Competitors such as Mitsui O.S.K Lines and Nippon Yusen Kaisha of Japan and Belgium’s Euronav NV all confirmed owning fewer. No one could be reached at the National Shipping Company of Saudi Arabia, but the company says on its website that it owns 31 super tankers.

Iran was forced to rely more on NITC, the former state-owned shipping company, to transport crude oil after Europe imposed sanctions on Iran and banned insurers from covering ships carrying the Iranian crude.

U.S. and European sanctions took a toll on Iran’s exports, cutting them in half since 2012. But Iran still had buyers in Asian countries like China and South Korea, where NITC ships carried oil.

‘No other company in the world owns that number of VLCCs’

—Nasrollah Sardashti, NITC’s commercial director

As Iran and world powers close in on a deal that would lift sanctions in exchange for curbs on its nuclear program, Tehran has been seeking to build ties with European companies that have traditionally traded with the Persian Gulf country.

Ali Akbar Safaei, the managing director of the NITC, said in an interview that the company is in talks with insurance companies that are part of London’s International Group of P&I Clubs—a form of oil-shipping insurance coverage that pools insurers’ resources to cover high risks—as the company seeks to speed up its return to Europe.

“We have resumed our connections with partners in the maritime field” in the EU, he said. “All conditions are there to call at European ports” when sanctions are lifted.

‘We have resumed our connections with [EU] partners in the maritime field... All conditions are there to call at European ports [when sanctions are lifted].’

—NITC Managing Director Ali Akbar Safaei

Mr. Safaei also mentioned contacts with European safety-rating agencies, shipping logistics agencies and finance houses.

In addition to industrywide sanctions on Iran’s oil industry, the EU also banned dealings with NITC, though a European court deemed the decision illegal and “unreasonable” last year. But the EU subsequently reinstated sanctions against the company.

Mr. Safaei said a team of experts working for the company is now assessing the monetary value of the losses caused by sanctions and “then we will decide the course of action.”

【11】

Iran Wants to Double Oil Exports After Sanctions Lifted

Exports could hit 2.3 million barrels a day, deputy oil minister Moazami says

July 5, 2015

In this file photo from December 2014, an Iranian oil worker rides his bicycle at an oil refinery south of the capital Tehran

TEHRAN—Iran wants to double its crude exports soon after sanctions are lifted and is pushing other members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries to renew the cartel’s quota system, a top Iranian official said.

Both developments could set up a clash with Saudi Arabia, which is scrambling to raise its own export numbers and has opposed the return of production limits on individual OPEC members.

Iran’s efforts underscore how the country’s full return to the export market would upend the status quo among leading producers if Tehran clinches a deal with six world powers that would lift sanctions in exchange for curbs on its nuclear activities.

The latest deadline for a deal is Tuesday and officials said the elements of an agreement were falling into place over the weekend, though there were still important sticking points that could scuttle it.

Should sanctions be lifted, Iran’s deputy oil minister for planning and supervision, Mansour Moazami, said in an interview that his country’s oil exports would reach 2.3 million barrels, compared with around 1.2 million barrels a day today.

“We are like a pilot on the runway ready to take off. This is how the whole country is right now,” he said.

Iran is already in contact with former oil buyers in the European Union—traders such as Vitol Group and big oil producers such as Royal Dutch Shell PLC, Total SA and Eni SpA—as well as existing importers in Asia to help absorb the potential new shipments or invest in new fields if sanctions are lifted, according to the oil ministry and the companies.

Iran’s oil reserves are the fourth-largest in the world and its production capacity stands at about four million barrels a day—making it the second-biggest producer in OPEC if its output were unrestricted.

EU sanctions in 2012 banned the import of Iranian oil and prohibited most big oil companies from working with Iran, while American pressure forced Asian nations to reduce purchases.

The return of Iran’s oil would come at a sensitive time for the world’s oil markets.

The price of Brent crude, the global benchmark, has fallen by more than 45% in the past year, trading at around $61 a barrel, as supply outpaces demand by about two million barrels on any given day.

OPEC nations, especially Iraq and Saudi Arabia, have been pumping at record levels while production in the U.S.—a non-OPEC country—has shown signs of resilience.

Oil-market analysts have expressed skepticism that Iran could increase production as quickly as it says it will.

A senior OPEC delegate said some rival producers doubted Iran has the production and export facilities to reach its previous production levels of 4.2 million barrels a day.

Dr. Moazami said he didn’t expect prices to fall because global economic growth would drive demand higher. He said Iran’s own forecast for oil prices is now $70 a barrel by the end of 2015.

Dr. Moazami said Iran was pushing OPEC to return to individual production allocations or quotas. OPEC discontinued quotas in 2011 because they caused friction and member countries didn’t respect them anyway.

It replaced quotas with a collective ceiling—currently at 30 million barrels a day. But even that is seen as more of a guideline than a limit these days, OPEC officials have said, as the group is currently producing more than 31 million barrels a day.

Restoring quotes would need unanimous approval by the organization, something that is unlikely at this stage given the Saudi opposition.

“Their mechanism right now is not proper. It has to return to its past ability and capacity,” Dr. Moazami said of OPEC.

At its last meeting on June 5, Iran’s oil minister Bijan Zanganeh informed other OPEC ministers his country’s production would increase if sanctions are lifted and offered to reinstate the quotas.

But the proposal was brushed off by his Saudi counterpart, Ali al-Naimi, who said the output boost shouldn’t be discussed until it materializes and ruled out the return of production allocations, according to Gulf Arab and Iranian officials.

The senior OPEC official said the organization would return to quotas only if it “is absolutely necessary” and the recent price crash didn’t warrant such a decision.

【17】

《Washington Institute》

Iran Seen from Beijing

Kevjn Lim June 11, 2015

China views Iran as a central element in its much-touted Silk Road Economic Belt, which aims to extend Beijing's influence overland through Central Asia to the Persian Gulf and Europe.

Although China has long been Iran's largest oil customer, international sanctions recently relegated the Islamic Republic from third to sixth place among Beijing's suppliers -- a list consistently topped by Iranian rival Saudi Arabia. Similarly, while China's bilateral trade with Iran reportedly expanded to around $50 billion by late 2014, it remains dwarfed nearly elevenfold by its trade with the United States.

Given these figures, why does Iran play a seemingly disproportionate role in Beijing's regional calculus, often to the puzzlement of its much larger energy and trade partners in Riyadh and Washington? Diplomatic brinksmanship aside, much of the answer lies in Iran's geostrategic value as a key hub in China's westward overland thrust, which Beijing views as essential to countering both Washington's eastward pivot and U.S. naval superiority.

BACKGROUND

China and Iran's durable ties stretch back as far as the Han and Parthian empires, when the two civilizations were trade partners on the ancient Silk Road. When the Arabs invaded Iranshahr in the seventh century, Peroz III, scion of the swansong Sassanian monarch Yazdgird III, sought and was offered refuge in Tang China by the Emperor Gaozong. In modern times, despite substantive ideological differences, Ruhollah Khomeini and Mao Zedong instilled both countries with revolutionary legacies that rejected imperial hegemony and foreign exploitation, putting them on the same side against the U.S.-led status quo.

Over time, China has become Iran's least unreliable -- not to say most reliable -- major power ally and a key pivot for counterbalancing the United States. During Iran's withering eight-year war with Iraq, Beijing was the only major power to supply Tehran with arms (though it did the same for Baghdad). And in 1985, the two governments signed a stealth nuclear cooperation deal during a visit by then parliamentary speaker Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. Cooperation went from strength to strength until 1997, when U.S. pressure over the previous year's Taiwan Strait crisis spurred China to suspend nuclear and missile assistance to Tehran. By then, however, years of Chinese and North Korean technical assistance had already helped Iran establish a homegrown missile production industry, a key pillar of its defense posture.

On the economic front, Beijing has reduced its oil imports from Iran in recent years to preserve the U.S. sanctions waivers it enjoys. Owing to Iran's sanctions-induced reductions, however, it continues to buy half of Iran's crude exports. In addition to the lower prices Tehran is offering because of sanctions, Iranian supplies matter greatly to Beijing because the Gulf's other major energy producers are U.S. partners.

EMPHASIZING THE EURASIAN HEARTLAND

China has been pushing west in the context of the Silk Road Economic Belt (Sichouzilu jingjidai) introduced by President Xi Jinping in September 2013. This "westward march" had already been advocated in 2011 by Wang Jisi(北京大学国际关系学院院长王缉思), one of the country's most lucid strategic minds, with the aim of meeting and counterbalancing President Obama's eastward pivot. Under the Xi administration, Beijing's immediate Silk Road priorities appear to be threefold:

Securing the overland flow of energy from neighboring Central Asia (and Russia) to offset the risk of maritime interdiction, especially at two sensitive waterways: the Strait of Malacca (through which 80 percent of Chinese oil transits) and the Strait of Hormuz (through which about two-fifths of its oil imports pass).

Leveraging development projects to pacify the restive but energy-rich western province of Xinjiang, where Uyghur separatists advocating the establishment of an East Turkestan state have repeatedly taken up arms against the Han Chinese.

Encouraging greater regional stability and integration by locking China's western neighbors into a zone of prosperity extending to Europe, with Beijing at its political and economic nexus.

China is the world's largest net importer of oil. Given the risks of maritime interdiction, the need for overland energy conduits is particularly important. Accordingly, two new pipelines came onstream in 2006 and late 2009. The first pumps oil mostly from Kazakhstan's northern Caspian region of Atyrau through China's Xinjiang province and toward the coast, amounting to roughly 4 percent of the 6.2 million barrels per day that China imported in 2014. The other pipeline brings natural gas mainly from the Saman-Depe field in Turkmenistan, which has been China's largest supplier since 2012. In 2013 terms, Turkmen gas accounted for about half of China's 53 billion cubic meters in annual gas imports and about a sixth of its overall gas consumption. Ashgabat plans to more than double these exports by 2020.

In accordance with the Chinese saying "if you want to prosper, first build roads" (yao xiang fu, xian xiu lu), Beijing has also been modernizing the vast network of roads and railways crisscrossing Central Asia, financing its efforts through the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Silk Road Fund. In 2012, it completed a rail line extending from Khorgos to Zhetygen, Kazakhstan, and onward to Western Russia and Europe, paralleling an existing line from Xinjiang's provincial capital of Urumqi through China's Dzungarian Gate (Alashankou) and into Kazakhstan's largest city, Almaty. This east-west corridor may eventually cleave through Iran to the Gulf. According to strategist Gao Bai, Beijing has sought to offset U.S. naval superiority by building a high-speed railway capable of projecting power from China's eastern seaboard into the Eurasian interior -- a continental hedge of sorts in the event of maritime trouble. And despite the challenges that a China-bound Eurasian order could pose to Russia, President Vladimir Putin reportedly gave Xi Jinping his blessing in October 2014 after the latter agreed to include the Trans-Siberian and BAM railways in the Silk Road Economic Belt.

IRAN'S GEOSTRATEGIC VALUE

So where does Iran fit into all this? Tehran is not a dominant actor in Central Asia, partly because of its deference to Moscow, and also because the countries in question remain wary of Iranian soft-power penetration. Even its trade with the Central Asian republics is conspicuously modest. Rather, Iran fills a geostrategic role as their most convenient non-Russian access route to open waters, and the only east-west/north-south intersection for Central Asian trade. In May 1996, Iran and Turkmenistan forged this missing link by inaugurating a 300-kilometer railway between Mashhad and Tejen. And in December 2014, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Iran inaugurated a railway from Uzen (Zhanaozen) to Gorgan and onward to Iran's Gulf ports.

Meanwhile, Turkmenistan and Iran completed a gas pipeline in 1997 linking Korpeje to Kordkuy, followed in 2010 by the Dauletabad-Serakhs-Khangiran pipeline. Turkmenistan supplies about 14 billion cubic meters of gas annually to Iran, as well as a large proportion of the country's imported electricity. Similarly, Kazakh oil sent via Caspian Sea tankers has powered Iran's hydrocarbon-deprived northern provinces, in a swap arrangement that sees Tehran selling equivalent amounts on Astana's behalf via the Persian Gulf. In addition to the shorter export pathways it offers, energy relations with Iran are tempting given Russia's long history of price extortion with its Central Asian vassals. Nevertheless, such relations have not been entirely smooth -- bureaucratic disagreements have emerged with Tehran over transit fees, fuel prices, payment methods, and the like.

For Beijing, Iran's geostrategic value is enhanced by its position astride one of China's two overland bridges to the west. The other bridge skirts the northern coast of the Caspian through Kazakhstan and southwestern Russia near the Caucasus region, but Iran arguably presents the more important route because it connects with both Europe and the Gulf. Given this continental anchor, the Islamic Republic has taken on an importance in Beijing that exceeds the size of its domestic market or its role as energy purveyor.

NEXT STEPS

If a nuclear agreement with the United States brings sanctions relief to Tehran, China will no doubt intensify its presence in Iran's economy. Likewise, it will encounter fewer obstacles in extending its road, rail, and pipeline networks through the land bridge that is the Iranian plateau. A nuclear deal could also pave the way for Iran's full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a request that has been rejected since 2008 on the grounds that Tehran is under UN sanctions. The SCO, whose full members include China, Russia, and all of the Central Asian republics except Turkmenistan, is widely perceived as a counterbalance to NATO and the United States, so Iran almost certainly regards it as an additional layer of insurance in the event of future hostilities with the West.

Against this backdrop, Washington has admittedly precious little room for maneuver. Containing both China and Iran is a surefire way to drive them together. And counteracting Iran while accommodating China -- or, more improbably, vice versa -- would leave loopholes that either could exploit. The more the White House is distracted by Persian imponderables, the less robust its "rebalancing" of resources toward Asia will be, which eminently suits Beijing. The Middle East and Iran in particular are Washington's more immediate priorities, but China represents its most important long-term foreign policy challenge. How Beijing and Tehran interact in the meantime will have significant consequences for America's grand strategy.

Kevjn Lim is an independent researcher focusing on foreign and security policy in the Middle East, where he has been based for nearly a decade.

评论

目前还没有任何评论

登录后才可评论.