陇山陇西郡

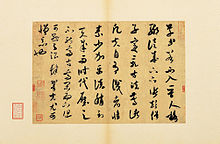

宁静纯我心 感得事物人 写朴实清新. 闲书闲话养闲心,闲笔闲写记闲人;人生无虞懂珍惜,以沫相濡字字真。- decorative handwriting or handwritten lettering.

synonyms: handwriting, script, penmanship, hand, pen "the scribe's meticulous calligraphy"- the art of producing decorative handwriting or lettering with a pen or brush.

East Asia[edit]

The Chinese name for calligraphy is shūfǎ (書法 in Traditional Chinese, literally "the method or law of writing");[24] the Japanese name shodō (書道, literally "the way or principle of writing"); the Korean is seoye (Korean: ??/書藝, literally "the art of writing"); and the Vietnamese is Th? pháp (書法, literally "the way of letters or words"). The calligraphy of East Asian characters is an important and appreciated aspect of East Asian culture.

History[edit]

A Vietnamese calligrapher writing in Hán-Nôm in preparation for T?t, at the Temple of Literature, Hanoi (2011)

A Vietnamese calligrapher writing in Hán-Nôm in preparation for T?t, at the Temple of Literature, Hanoi (2011)In ancient China, the oldest Chinese characters existing are Jiǎgǔwén (甲骨文) characters carved on ox scapulae and tortoise plastrons, because the dominators in Shang Dynasty carved pits on such animals' bones and then baked them to gain auspice of military affairs, agricultural harvest, or even procreating and weather. During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made, the characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved.(Keightley, 1978). With the development of Jīnwén (Bronzeware script) and Dàzhuàn (Large Seal Script) "cursive" signs continued. Moreover, each archaic kingdom of current China had its own set of characters.

In Imperial China, the graphs on old steles—some dating from 200 BC, and in Xiaozhuan style—are still accessible.

About 220 BC, the emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first to conquer the entire Chinese basin, imposed several reforms, among them Li Si's character unification, which created a set of 3300 standardized Xiǎozhuàn(小篆) characters.[25] Despite the fact that the main writing implement of the time was already the brush, few papers survive from this period, and the main examples of this style are on steles.

The Lìshū(隶书) style (clerical script) which is more regularized, and in some ways similar to modern text, have been also authorised under Qin Shi Huangdi.[26]

Kǎishū style (traditional regular script)—still in use today—and attributed to Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303–361) and his followers, is even more regularized.[26] Its spread was encouraged by Emperor Mingzong of Later Tang (926–933), who ordered the printing of the classics using new wooden blocks in Kaishu. Printing technologies here allowed a shape stabilization. The Kaishu shape of characters 1000 years ago was mostly similar to that at the end of Imperial China.[26] But small changes have been made, for example in the shape of 广 which is not absolutely the same in the Kangxi Dictionary of 1716 as in modern books. The Kangxi and current shapes have tiny differences, while stroke order is still the same, according to old style.[27]

Styles which did not survive include Bāfēnshū, a mix made of Xiaozhuan style at 80%, and Lishu at 20%.[26] Some variant Chinese characters were unorthodox or locally used for centuries. They were generally understood but always rejected in official texts. Some of these unorthodox variants, in addition to some newly created characters, compose the Simplified Chinese character set.

Technique[edit]

Traditional East Asian writing uses the Four Treasures of the Study (文房四寶/文房四宝): the ink brushes known as máobǐ (毛笔) to write Chinese characters, Chinese ink, paper, and inkstone, known as the Four Friends of the Study (Korean: ????, translit. 文房四友) in Korea. In addition to these four tools, desk pads and paperweights are also used.

The shape, size, stretch, and hair type of the ink brush, the color, color density and water density of the ink, as well as the paper's water absorption speed and surface texture are the main physical parameters influencing the final result. The calligrapher's technique also influences the result. The calligrapher's work is influenced by the quantity of ink and water he lets the brush take, then by the pressure, inclination, and direction he gives to the brush, producing thinner or bolder strokes, and smooth or toothed borders. Eventually, the speed, accelerations, decelerations of the writer's moves, turns, and crochets, and the stroke order give the "spirit" to the characters, by greatly influencing their final shapes.

Styles[edit]

Cursive styles such as xíngshū (semi-cursive or running script) and cǎoshū (cursive or grass script) are less constrained and faster, where more movements made by the writing implement are visible. These styles' stroke orders vary more, sometimes creating radically different forms. They are descended from Clerical script, in the same time as Regular script (Han Dynasty), but xíngshū and cǎoshū were used for personal notes only, and never used as a standard. The cǎoshū style was highly appreciated in Emperor Wu of Han reign (140–187 AD).[26]

Examples of modern printed styles are Song from the Song Dynasty's printing press, and sans-serif. These are not considered traditional styles, and are normally not written.

Influences[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Japanese calligraphy, the word "peace" and the signature of the Meiji period calligrapher ?ura Kanetake, 1910

Japanese calligraphy, the word "peace" and the signature of the Meiji period calligrapher ?ura Kanetake, 1910Japanese and Korean calligraphies were greatly influenced by Chinese calligraphy. The Japanese and Korean people have also developed specific sensibilities and styles of calligraphy. For example, Japanese calligraphy go out of the set of CJK strokes to also include local alphabets such as hiragana and katakana, with specific problematics such as new curves and moves, and specific materials (Japanese paper, washi 和紙, and Japanese ink).[28] In the case of Korean calligraphy, the Hangeul and the existence of the circle required the creation of a new technique which usually confuses Chinese calligraphers.

Temporary calligraphy is a practice of water-only calligraphy on the floor, which dries out within minutes. This practice is especially appreciated by the new generation of retired Chinese in public parks of China. These will often open studio-shops in tourist towns offering traditional Chinese calligraphy to tourists. Other than writing the clients name, they also sell fine brushes as souvenirs and lime stone carved stamps.

Since late 1980s, a few Chinese artists have branched out traditional Chinese calligraphy to a new territory by mingling Chinese characters with English letters; notable new forms of calligraphy are Xu Bing's square calligraphy and DanNie's coolligraphy or cooligraphy.

Mongolian calligraphy is also influenced by Chinese calligraphy, from tools to style.

Calligraphy has influenced ink and wash painting, which is accomplished using similar tools and techniques. Calligraphy has influenced most major art styles in East Asia, including ink and wash painting, a style of Chinese, Korean, Japanese painting, and Vietnamese painting based entirely on calligraphy.

*8

-

?? 大学同学非常喜欢我的书法作品,以得到我的一幅书法为荣。往往临近春节,他们会通过微信向我索要春联,甚至在美国的同学也一样。在异国他乡,当把春联贴在家里,立即弥漫浓浓的中国春节气氛。

“能受天磨真铁汉,不遭人嫉是庸才”

“斜日微明双鸟下,乱山忽断一帆来”

吉祥如意,福星高照

“竹无俗韵,梅有奇香”

庆祝毕业35周年会上

????