There is a new book about the rise of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Can you guess the colour of its cover?

Bright red books have been understandably mocked by the China-watcher community. Yet we should cut the authors some slack as this is most certainly the publishers’ decision. They know how to market a book which appeals to the masses, no matter what the sneering specialists might say.

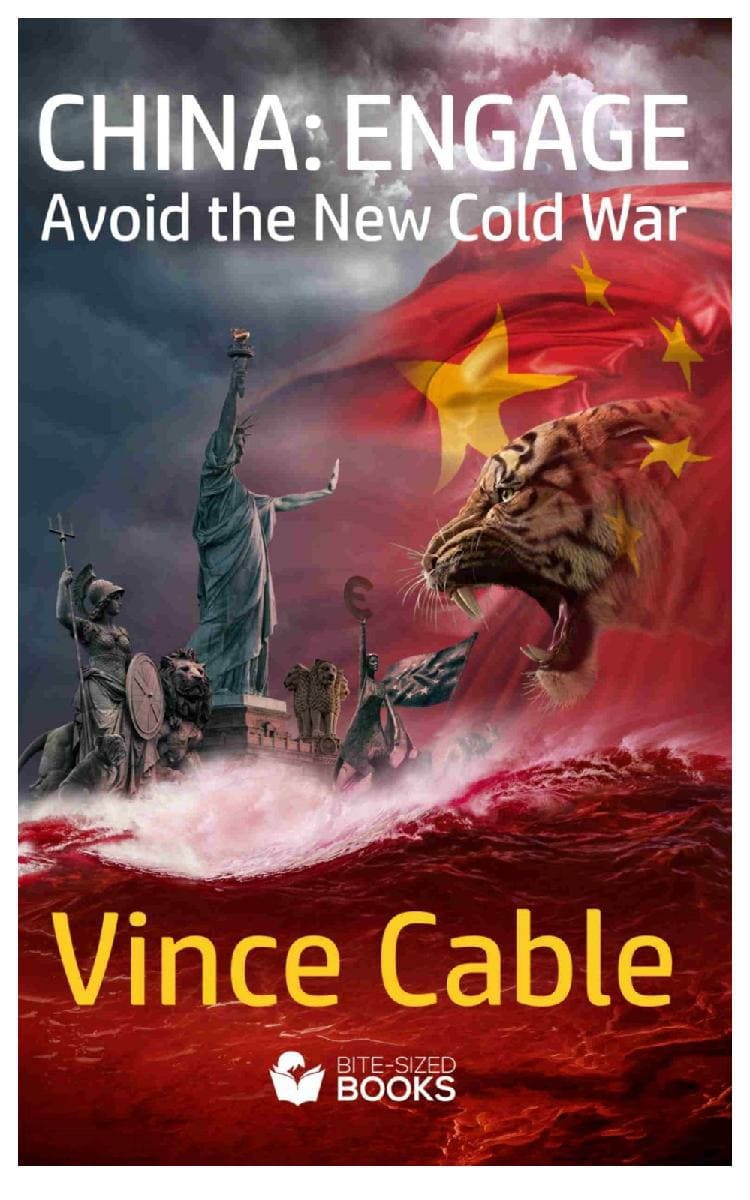

Book cover of China: Engage! Avoid the New Cold War. Photo: Gray Sergeant.

Book cover of China: Engage! Avoid the New Cold War. Photo: Gray Sergeant.

I feel somewhat relieved to discover that volumes bound in deep red are a minority amongst my small China collection, and those that do opt for this cliché colouring, Odd Arne Westad’s Restless Empire and Jonathan Fenby’s Tiger Head, Snake Tails to mention just two, are both thoroughly well researched and sound.

The new book by the former leader of the British Liberal Democrat (Lib Dem) party, and former Business Secretary, Sir Vince Cable takes this colouring to a whole new level. The cover of China: Engage! Avoid the New Cold War features a colossal red wave hurtling towards the West’s ladies of liberty. Striking enough, don’t you think?

The fact that the wave, as it breaks, morphs into the Chinese national flag and a roaring tiger only adds to the absurdity. The designer should have chucked in a few raging dragons for good measure – why hold back? Yet it is the book’s content which is the real problem.

While concise and up to date, in that it covers the early stages of the coronavirus outbreak, as well as easy to read, the book has its drawbacks. Some incredibly important topics are skimmed over and simplified.

More frustrating still , those areas where research has actually been undertaken remain, like a dodgy Lib-Dem election leaflet bar chart, free from citations – leaving the reader unable to discover the source of the facts. The book would have hugely benefited from the addition of some referencing, and a few more edits for that matter. And, well, a bit more research.

Depending on which chapter you read, Cable identifies either what he calls “geo-economics” or technology battles as being the main driver of the “new Cold War.” The first three main chapters, which make up half the book, are devoted to these areas, in which he argues that the People’s Republic is either already on top or soon to emerge as the world’s number one.

By any meaningful definition of economic size China is already the biggest in the world and more importantly, Cable argues, the trends continue to favour it over the United States. He pushes back against the doom-mongers whom he believes have continually underestimated China’s ability to adapt, innovate and reform.

Concerns about the country’s aging population, declining labour force, and high levels of debt are swiftly addressed. Likewise, not only is China making extraordinary advances in telecommunications, Artificial Intelligence and big data but Western security concerns about its use of such technologies are largely unfounded, according to Cable.

Vince Cable. File photo: Nick Clegg, via Wikicommons.

The argument is clear. China’s rise is unchallengeable and we, the liberal democratic West, must learn to live with this reality. The current rush to take sides, Cable believes, is not only unwise but dangerous. Yet despite advocating fence-sitting, a position a Lib-Dem would know a thing or two about, Cable’s true sympathies ooze from every page.

For starters, by focusing on economics Cable treads on fairly safe ground: only the most observant China-watching economist would dare quibble with his predictions. He relegates more contentious questions such as talk of Chinese expansionism, which he believes is exaggerated, and ideological battles, which he brands as “virtue signalling”, to two significantly shorter, and sketchier, chapters.

Only three short paragraphs are devoted to the South China Sea, even though Cable acknowledges the international illegality of Beijing’s claims to the territorial waters surrounding “reclaimed rocks and islets.” Presumably he means artificial islands decked out with airstrips and missile systems. Yet such details, it would seem, are ultimately inconsequential as Cable reassures us that China has “no incentive to disrupt sea lanes.”

US military air crafts on South China Sea. File Photo: Seaman Tomas Compian via USGov.

Even fewer words are then devoted to Taiwan, an area where Cable himself acknowledges that “China threatens military aggression”. Stranger still, the accompanying paragraph seeks to reassure us again despite this opening claim. He opts for the phrase “restoration of Taiwan” rather than annexation to describe Beijing’s goals. China, Cable claims, has been “highly pragmatic” by welcoming Taiwanese tourists and investors. Moreover, he notes, General Secretary Xi Jinping’s position is merely a continuation of a stance held by previous Chinese leaders.

While there is truth to the last claim it ignores Xi’s assertion that the Taiwan issue cannot be left for another generation to resolve. Nor does it acknowledge China’s ramped-up military manoeuvres against the island and attempts to isolate Taipei on the world stage since 2016 (pragmatism… my arse!). Clearly, such details were too nuanced to fit into a few sentences.

More worrying analysis is to be found in the concluding lines of this very short section. Here the Taiwanese themselves and their American allies are singled out for blame. Ultimately, in Cable’s mind, they are the provocateurs. Which demonstrates that his understanding of current cross-strait relations is as shaky as his understanding of Washington’s Taiwan policy.

While you can blame the United States all you like for shaking up the international economic order in recent years, and this book repeatedly does, you cannot pin the blame on the Trump administration and least of all on President Tsai Ing-wen for rising tensions in the Taiwan Strait.

Tsai Ing-wen. Photo: Office of the President of Taiwan, via Flickr.

It may be a small point but we should tip our hats to Cable for, on two occasions, grouping Taiwan in a list of “countries”. While this may have been inadvertent it nevertheless treats the Taiwanese with a welcome degree of respect which he, sadly, does not show to Tibetans or Uighurs.

In a section presumably designed to address us liberals and social democrats, patronisingly described as people “who feel the need to make a statement on ‘human rights,” he regurgitates the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) line without comment. Chinese authorities, it is asserted, “have no problem with accommodating religions,” the problem only lies with minorities who seek self-determination (tell that to Xinjiang’s Hui communities). China, it would seem, merely wants to prevent a bloody breakup à la Yugoslavia.

Moreover, whatever the wrongs which occur in these regions, Cable – now speaking for himself – asserts that the West has already accepted Chinese sovereignty over these areas so should not cause offence by criticising Beijing’s internal policies.

This dismissal of a values-based foreign policy is more than just a former business secretary being a practitioner of realpolitik. As I wrote earlier, Cable’s sinister sympathies ooze from the pages. You cannot help but notice his admiration for the CCP’s system which he describes as a “competent technocracy” delivering “continuity, cohesion and discipline.” It is a system which he credits with promoting the public good in the realms of climate change and pandemic management. Although he does not substantiate such contestable claims, his main point is clear: such public goods are not even pursued by the chaotic Trumpian populists who have been brought to power via democratic votes.

Xi Jinping. File photo: Kremlin.

Xi Jinping. File photo: Kremlin.

Occasionally his fawning on the communists in Beijing is masked with mystical talk of a new dynasty and the mandate of heaven. This, after all, is a much more palatable way to discuss dictatorship and authoritarianism. Yet most of the time he plays it straight and clearly articulates the CCP’s narrative in 21st century language.

There is a wide range of political systems, we are told, with varying degrees of political participation. We are also informed that in China there is a “different meaning of human rights.” In addition, Cable reminds us that dissent is actually allowed in China providing it is localised, providing it is non-political, and providing, of course, it is not organised or part of a movement. So that’s settled, then – quit your whining!

What I ought to remind you here is that this is the former leader of the Liberal Democrats we are discussing. You would be forgiven for forgetting this, given the book’s pooh-poohing of both liberal and democratic values which it suggests are not conducive for stability or wise governance. Both of which, the book argues, are products of “the Chinese model.”

Hongkongers would only need to read the few pages dealing with their own struggle to confirm this assessment of Cable’s view. This part begins by telling readers that it would have been “very understandable” if Beijing had just annexed Hong Kong. It brushes aside the arrest of “some democratic campaigners” and the tighter controls over the media and freedom of expression underthe new National Security Law, and accuses the protesters of backing the CCP into a corner. It ends by discussing, in much greater detail, the city’s economic prospects going forward.

It is no surprise that Cable retreats to his economic comfort zone in his discussion of Hong Kong and of China’s rise as a whole. After all, he regards the whole situation as a fait accompli. The People’s Republic of China has risen and will continue to rise, and the West just needs to get on board and make the most of the big opportunities on offer. It is as simple as that.

In this sense, reading China: Engage!, or at least the first few chapters, is a good intellectual challenge to those of us who advocate a values-based foreign policy. The rest, although poorly researched, should be read with concern.

While it should be unremarkable that a former business secretary advocates doing business, it is surprising to hear a Liberal Democrat giving succour to the illiberal undemocratic “Chinese model”. Clearly, the allure of China and its authoritarian system is much greater than many of us feared.

Chris Patten. Photo: Tom Grundy/HKFP.

Then again, maybe Sir Vince is just crassly currying favour with Beijing. He would not be the first former high-ranking British parliamentarian to do so. In 1993, Chris Patten, then Governor of Hong Kong, was bluntly advised by the former Labour Prime Minister Lord Callaghan not to martyr himself doing much about democracy or the rule of law prior to the handover.

Lord Callaghan, incidentally, was on his way to a meeting of the “globally illustrious” in Shanghai, a fact which Patten later commented on in his book East and West:

“It is the sort of trip all of us in politics hope will arrive at regular intervals during our years of retirement – the chance to exchange with our ageing peers a few views from the summit about what is happening down on the plain before the obituary columns take us to their bosoms.”

I look forward to seeing the line-up for the next meeting of the Anglo-Chinese Golden Era Forum for Win-Win Cooperation and Mutual Understanding… or whatever they call it.

by

by