The Bank of Canada has mostly ignored the role that corporations play in setting prices. Instead, it has continued to suggest that raising wages will lead to higher prices (a wage-price spiral). For example, when the Bank increased interest rates in October, they mentioned wages 9 times, and failed to mention corporate profits at all.

Such an approach is disingenuous. We can see that average wage increases are lower than inflation across the board, while corporate profits are increasing.

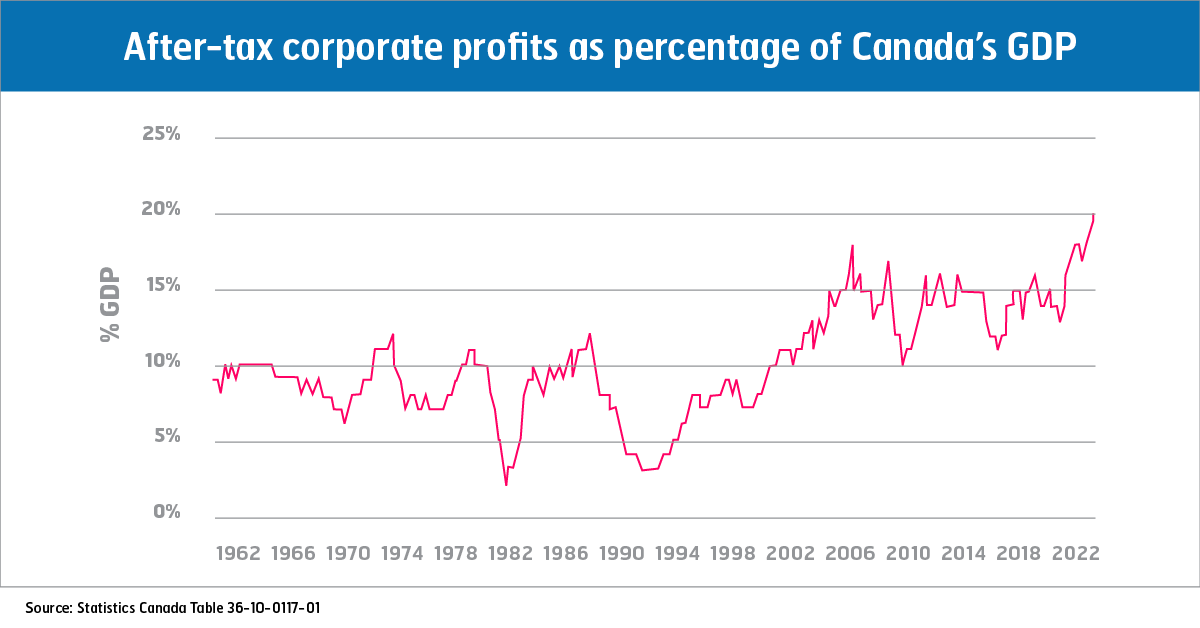

In fact, as a share of Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP), after-tax corporate profits have reached a 60-year high. GDP is the monetary value of all finished goods and services made within a country during a given period. It’s often used to estimate the size of an economy. In the second quarter of 2022 (the months of April, May, and June), after-tax corporate profits accounted for 20% of Canada’s GDP. This is two percentage points higher than the pre-financial crisis high of 18% that we saw in 2005, and more than double the average we saw between 1960 and 2000.

Why is the Bank of Canada ignoring the role of corporate profits in rising prices? One reason is that mainstream economic theory says it’s natural for corporations to set prices as high as they can to maximize profits. The idea is that if corporations set prices too high, consumers will switch to a more affordable option, keeping prices in check.

The problem is that this only works if there is healthy competition in the market, and new businesses can make money by offering goods and services at lower prices. This is difficult in Canada because our laws favour corporate mergers and monopolies, making it harder for new businesses to compete.

Anti-competitive behaviour isn’t new in Canada, and neither are our concerns about it. There’s been public outcry over a number of large corporate mergers in the past several years, and the federal government just launched a long-awaited competition review in November. Throughout this process, we will need to hold the government to account to improve our competition laws and keep prices in check.

But while improvements to competition law will help, it’s not the whole picture. There are also Canadian industries with several players, such as Canada’s big banks, which maintain higher prices than we would expect in a competitive marketplace. This demonstrates that competition isn’t the magic fix that economists sometimes make it out to be – especially when it comes to goods and services that are necessities, like shelter, food, and energy. Corporations know that consumers will pay more for things that they need, even if they really can’t afford it. For true necessities, it makes sense to have a public option that takes profiteering out of the equation – like public energy companies.

Finally, it’s important to note that one of the primary drivers of higher after-tax corporate profits has been the dramatic corporate tax cuts that governments at both the federal and provincial levels have implemented since 2000. This has resulted in a huge transfer of wealth from governments and public services into private hands. We need our governments to recognize that this trickle-down approach has failed, and to implement a better balance in corporate taxation.