陇山陇西郡

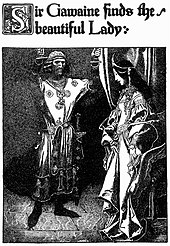

宁静纯我心 感得事物人 写朴实清新. 闲书闲话养闲心,闲笔闲写记闲人;人生无虞懂珍惜,以沫相濡字字真。国王亚瑟和圆桌武士加温: 丑陋的女巫倾城的美女

国王亚瑟被俘,本应被处死刑,但对方国王见他年轻乐观,十分欣赏,于是就要求亚瑟回答一个十分难的问题,如果答出来就可以得到自由。

这个问题就是:“女人真正想要的是什么?”

亚瑟开始向身边的每个人征求答案:公主、牧师、智者……结果没有一个人能给他满意的回答。

有人告诉亚瑟,郊外的阴森城堡里住着一个老女巫,据说她无所不知,但收费高昂,且要求离奇。

期限马上就到了,亚瑟别无选择,只好去找女巫,女巫答应回答他的问题,但条件是,要和亚瑟最高贵的圆桌武士之一,他最亲近的朋友加温结婚。

亚瑟惊骇极了,他看着女巫,驼背、丑陋不堪、只有一颗牙齿,身上散发着臭水沟难闻的气味……而加温高大英俊、诚实善良,是最勇敢的武士。

亚瑟说:“不,我不能为了自由强迫我的朋友娶你这样的女人!否则我一辈子都不会原谅自己。”

加温知道这个消息后,对亚瑟说:“我愿意娶她,为了你和我们的国家。”

于是婚礼被公诸于世。

女巫回答了这个问题,“女人真正想要的,是主宰自己的命运。”

每个人都知道女巫说出了一条伟大的真理,于是亚瑟自由了。

婚礼上女巫用手抓东西吃、打嗝,说脏话,令所有的人都感到恶心,亚瑟也在极度痛苦中哭泣,加温却一如既往的谦和。

新婚之夜,加温不顾众人劝阻坚持走进新房,准备面对一切,然而一个从没见过面的绝世美女却躺在他的床上,女巫说:“我在一天的时间里,一半是丑陋的女巫,一半是倾城的美女,加温,你想我白天或是夜晚是哪一面呢?……”

这是个如此残酷的问题,如果你是加温,你会怎样选择呢?

……

当时人格心理学的教授话音一落,同学们先是静默,继而开始热烈的讨论,答案更是五花八门,不过归纳起来不外乎两种:白天是女巫,夜晚是美女,因为老婆是自己的,不必爱慕虚荣;另一种选白天是美女,因为可以得到别人羡慕的眼光,而晚上可以在外作乐,回到家一团漆黑,美丑都无所谓。听了大家的回答,教授没有发表意见,只说这故事其实有结局的,加温做出了选择。于是大家纷纷要求老师说出结果。

How about you? Your thought? She demands respect and integrity - that's life toward love. You ask for love, but think about if you know what's love - Character counts for guarantee your love, not money, not power. Your love is within yourself, so unique, nobody else can touch, except you, only you.

Here is the answer:

老师说,加温回答道:“既然你说女人真正想要的是主宰自己的命运,那么就由你自己决定吧!”女巫终于热泪盈眶,“我选择白天夜晚都是美丽的女人,因为我爱你!”

所有人都沉默了,因为没有一个人做出加温的选择。我们有时候是不是很自私?以自己的喜好去主宰别人的生活,却没有想过别人是不是愿意。而当你尊重别人、理解别人时,得到的往往会更多。

******* Acknowledgment - Sources of Inspiration: Reference "Inspire. Create. Resilience. Serve." **********************

My point? Someone else said: “女人真正想要的是什么?”

我认为尊重是两性关系中最基本最重要的要素。 来源: 再见二丁目 于 2015-09-25 14:28:56 [档案] [旧帖] [给我悄悄话] 本文已被阅读: 7387 次 (1700 bytes) 字体:调大/重置/调小 | 加入书签 | 打印 | 所有跟帖 | 加跟贴 | 当前最热讨论主题

我在两性关系中一定要获得足够的尊重, 而对对方,我一定要有足够的尊重才能真正地去爱他。 在我的概念中, 没有尊重就没有爱。 我觉得一旦你不尊重甚至开始嫌弃对方, 那么爱就不存在了。

当年有个朋友, 台湾来的, 嫁了一个美国人。 和他们一起出去吃过一次饭, 那顿晚餐, 让我隐隐觉得我对他们的婚姻不看好。 理由其实很简单, 就是这个丈夫在中餐面前时时刻刻显示出来的看低和嫌弃的神情。 在文化差异饮食习惯不同这个方面, 我的要求就是, 你可以不喜欢不适应, 但是要懂得起码的尊重。 你的爱人是在这样的文化教育熏陶出来的, TA是吃着中餐长大的。 我自己很难想象, 你爱一个人却可以同时嫌弃TA的背景,TA的文化。

当然, 饮食, 只是一个方面。 尊重应该体现在多方面。。。尊重对方独立的人格,思想,尊重对方的情感,尊重对方的空间, 尊重对方做喜欢或者认为重要的事,尊重对方生命中重要的人。。。

我每次听到妻子嫌弃丈夫能力不够, 不会赚钱, 或者丈夫嫌弃妻子邋遢, 没有生活情趣的,或者其他各种嫌弃时, 总是会想, 既然这样, 为什么还非要在一起?我的逻辑简单直接:既然嫌弃, 想必不会尊重, 没有尊重, 便没有爱,没有爱, 就该分开。

我觉得首先有了尊重, 才会互相理解,支持,帮助,才能够共同成长。有了尊重未必有爱, 可是有爱必然有尊重。

************************ Reference ****************

Historical truth:

Gawain

Gawain (/ɡ??we?n/, [?ɡawain]; also called Gwalchmei, Gualguanus, Gauvain, Walwein, etc.) is King Arthur's nephew and a Knight of the Round Table in the Arthurian legend. Under the name Gwalchmei, he appears very early in the legend's development, being mentioned in some of the earliest Welsh Arthurian sources.

He is one of a select number of Round Table members to be referred to as one of the greatest knights, most notably in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. In some spin-offs, Sir Gawain is the Green Knight. He is almost always portrayed as the son of Arthur's sister Morgause (or Anna) and King Lot of Orkney and Lothian, and his brothers are Agravain, Gaheris, Gareth, and Mordred. He was well known to be the most trustworthy friend of Sir Lancelot.[1] In some works, Sir Gawain has sisters as well. According to some legends, he would have been the true and rightful heir to the throne of Camelot, after the reign of King Arthur.[2][3]

Gawain is often portrayed as a formidable, courteous, and also a compassionate warrior, fiercely loyal to his king and family. He is a friend to young knights, a defender of the poor, and as "the Maidens' Knight", a defender of women as well. In some works, his strength waxes and wanes with the sun; in the most common form of this motif, his might triples by noon, but fades as the sun sets. His knowledge of herbs makes him a great healer,[4] and he is credited with at least three children: Florence, Lovell, and Gingalain, the last of which is also called Libeaus Desconus or Le Bel Inconnu, the Fair Unknown. Gawain appears in English, French and Celtic literature as well as in Italy where he appears in the architecture of the north portal in the cathedral of Modena, constructed in 1184.[5][6]

Name[edit]

Gawain is known by different names and variants in different languages. The character corresponds to the Welsh Gwalchmei ap Gwyar, and is known in Latin as Walwen, Gualguanus, Waluanus, etc.; in French as Gauvain; and in English as Gawain. The later forms are generally assumed to derive from the Welsh Gwalchmei.[7] The element Gwalch means hawk, and is a typical epithet in medieval Welsh poetry.[8] The meaning of mei is uncertain. It has been suggested that it refers to the month of May (Mai in Modern Welsh), rendering "Hawk of May", though scholar Rachel Bromwich considers this unlikely. Kenneth Jackson suggests the name evolved from an early Common Brittonic name *Ualcos Magesos, meaning "Hawk of the Plain".[8]

Not all scholars accept the gwalch derivation. Celticist John Koch suggests the name could be derived from a Brythonic original *Wolcos Magesos, "Wolf/Errant Warrior of the Plain."[9] Others argue that the continental forms do not ultimately derive from Gwalchmei. Medievalist Roger Sherman Loomis suggests a derivation from the epithet Gwallt Avwyn, found in the list of heroes in Culhwch and Olwen, which he translates as "hair like reins" or "bright hair".[10][11] Dutch scholar Lauran Toorians proposes that the Dutch name Walewein (attested in Flanders and Northern France c. 1100) was earliest, suggesting it entered Britain during the large settlement of Flemings in Wales in the early 12th century.[12] However, most scholarship supports a derivation from Gwalchmei, variants of which are well attested in Wales and Brittany. Scholars such as Bromwich, Joseph Loth, and Heinrich Zimmer trace the etymology of the continental versions to a corruption of the Breton form of the name, Walcmoei.[7]

Gwalchmei[edit]Gwalchmei was a traditional hero of Welsh legend whose popularity greatly increased after foreign versions, particularly those derived from Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, became known in Wales.[13] The early romance Culhwch and Olwen, written in the 11th century and eventually associated with the Mabinogion,[14] ascribes to Gwalchmei the same relationship with Arthur that Gawain is later given: he is Arthur's sister's son and one of his leading warriors.[8] However, he is mentioned only twice in the text; once in the extensive list of Arthur's court towards the beginning of the story, and again as one of the "Six Helpers" who Arthur sends with the protagonist Culhwch on his journey to find his love Olwen.[13] Unlike the other helpers he takes no further part in the action, suggesting he was added to the romance later, likely under the influence of the Welsh versions of Geoffrey's Historia.[13] Still, Gwalchmei was clearly a traditional figure; other early references to him include the Welsh Triads; the Englynion y Beddau (Stanzas of the Graves), which lists the site of his grave; the Trioedd y Meirch (Triads of the Horses), which praises his horse Keincaled (known as Gringolet to later French authors); and Cynddelw's elegy for Owain Gwynedd, which compares Owain's boldness to that of Gwalchmei.[8] In the Welsh Triads, Triad 4 lists him as one of the "Three Well-Endowed Men of the Isle of Britain" (probably referring to his inheritance),[15] while Triads 75 and 91 praise his generosity to guests and his fearlessness, respectively.[16] Some versions of Triads 42 and 46 also praise his horse Keincaled, echoing the Triads of the Horses.[17] A tale recorded by 16th-century century Welsh scholar Sion Dafydd Rhys claims that Gwalchmai destroyed three witches by trickery.[18]

The Gwyar (meaning "gore"[19] or "spilled blood/bloodshed"[20]) in Gwalchmei ap Gwyar is likely the name of Gwalchmei's mother, rather than his father as is the standard in the Welsh Triads.[7]Matronyms were sometimes used in Wales, as in the case of Math fab Mathonwy and Gwydion fab Dôn, and were also fairly common in early Ireland.[7] Gwyar appears as a daughter of Amlawdd Wledig in one version of the hagiographical genealogy Bonedd y Saint. Additionally, the 14th-century Birth of Arthur, a Welsh text adapting scenes from Geoffrey of Monmouth, substitutes Gwyar for "Anna", Geoffrey's name for Gawain's mother.[21] Other sources do not follow this substitution, however, indicating that Gwyar and Anna originated independently.[22]

In Geoffrey of Monmouth and other early literature[edit]A few references to Gawain appear outside Wales in the first half of the 12th century; for instance in his Gesta Regum Anglorum of around 1125, William of Malmesbury writes that "Walwen's" grave had been uncovered in Pembrokeshire during the reign of William the Conqueror; William recounts that Arthur's formidable nephew had been driven from his kingdom by Hengest's brother, though he continued to harry his enemies severely.[23] However, it was Geoffrey of Monmouth's version of Gawain in the Historia Regum Britanniae, written around 1136, that brought the character to a wider audience.[24] As in the Welsh tradition, Geoffrey's Gualguanus is the son of Arthur's sister, here named Anna, and her husband is Lot, the prince of Lothian and one of Arthur's key supporters. Gualguanus is depicted as a superior warrior and potential heir to the throne until he is tragically struck down by his traitorous brother Modred's forces.[25]

Geoffrey's work was hugely popular, and was adapted into many languages. The Norman version by Wace, the Roman de Brut, ascribes to Gawain the chivalric aspect he would take in later literature, wherein he favors courtliness and love over martial valor.[24] Several later works expand on Geoffrey's mention of Gawain's boyhood spent in Rome, the most important of which is the anonymous Medieval Latin romance The Rise of Gawain, Nephew of Arthur, which describes his birth, boyhood and early adventures leading up to his knighting by his uncle.[3]

In French literature[edit]Verse romances[edit]Beginning with the five works of Chrétien de Troyes, Gawain became a very popular figure in French chivalric romances in the later 12th century. Chrétien uses Gawain as a major character and establishes some characteristics that pervade later depictions, including his unparalleled courteousness and his way with women. His romances set the pattern often followed in later works in which Gawain serves as an ally to the protagonist and a model of knighthood to whom others are compared. However, in Chrétien's later romances, especially Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart and Perceval, the Story of the Grail, the title heroes prove morally superior to Gawain, who follows the rules of courtliness to the letter rather than the spirit.[24]

An influx of romances written in French appeared in Chretien's wake, and in these Gawain was characterized variously. In many of these "Gawain romances", such as Le Chevalier à l'épée and La Vengeance Raguidel, he is the hero; in others he aids the hero; sometimes he is the subject of burlesque humor.[24] In the many variants of the Bel Inconnu or Fair Unknown story, he is the father of the hero.[26]

Prose cycles[edit]In the Vulgate Cycle, he is depicted as a proud and worldly knight who demonstrates through his failures the danger of neglecting the spirit for the futile gifts of the material world. On the Grail quest, his intentions are always the purest, but he is unable to use God's grace to see the error in his ways. Later, when his brothers Agravain and Mordred plot to destroy Lancelot and Guinevere by exposing their love affair, Gawain tries to stop them. When Guinevere is sentenced to burn at the stake and Arthur deploys his best knights to guard the execution, Gawain nobly refuses to take part in the deed even though his brothers will be there. But when Lancelot returns to rescue Guinevere, a battle between Lancelot's and Arthur's knights ensues and Gawain's brothers, except for Mordred, are killed. This turns his friendship with Lancelot into hatred, and his desire for vengeance causes him to draw Arthur into a war with Lancelot in France. In the king's absence, Mordred usurps the throne, and the Britons must return to save Britain. Gawain is mortally wounded in battle against Mordred's armies, and writes to Lancelot apologizing for his actions and asking for him to come to Britain to help defeat Mordred.

Other medieval literatures[edit]German and Dutch[edit]The Middle Dutch Roman van Walewein by Penninc and Pieter Vostaert, and the Middle High German romance Diu Crône by Heinrich von dem Türlin are both dedicated primarily to Gawain, and in Wirnt von Grafenberg's Middle High German Wigalois he is the father of the protagonist.

English and Scottish[edit]For the English and Scots, Gawain remained a respectable and heroic figure. He is the subject of several romances and lyrics in the dialects of those countries. He is the hero of one of the greatest works of Middle English literature, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, where he is portrayed as an excellent, but human, knight. In The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle, his wits, virtue and respect for women frees his wife, a loathly lady, from her curse of ugliness. Other important English Gawain romances include The Awntyrs off Arthure (The Adventures of Arthur) and The Avowyng of Arthur.

These glowing portraits of Gawain all but ended with Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, which is based mainly, but not exclusively, on French works from the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate Cycles. Here Gawain partly retains the negative characteristics attributed to him by the later French, and partly retains his earlier positive representations, creating a character seen by some as inconsistent, and by others as a believably flawed hero. Gawain is cited in Robert Laneham's letter describing the entertainments at Kenilworth in 1575,[27] and the recopying of earlier works such as The Greene Knight suggests that a popular tradition of Gawain continued. The Child Ballads include a preserved legend in the positive light, The Marriage of Sir Gawain a fragmentary version of the story of The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle. He also appears in the rescue of Guinevere and plays a significant role though Lancelot overshadows him. In Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, Guinevere is found guilty, however, Lancelot returns to help Guinevere to escape from the castle. Although, Mordred has sent to word to King Arthur, Arthur sends a few knights to capture Lancelot, and Gawain, being a loyal friend to Lancelot, refuses to take part of the mission. The battle between Lancelot and Arthur's knights results in Gawain's two sons and his brothers, except for Mordred, being slain. This begins the estrangement between Lancelot and Gawain, thus drawing Arthur into a war with Lancelot in France. While King Arthur is deployed to France, Mordred takes control of the throne, and takes advantage of the kingdom. Gawain wages two wars between Mordred and Lancelot. He is mortally wounded in a duel against Lancelot who later lies for two nights weeping at Gawain's tomb. Before his death, Gawain repents of his bitterness towards Lancelot and forgives him, while asking him to join forces with Arthur and save Camelot.[28]

Character[edit]Sir Gawain in particular of all Arthur’s knights is known for his courteousness and compassion. In "Gawain: His Reputation, His Courtesy and His Appearance in Chaucer’s Squire’s Tale," B.J. Whiting collected quantitative evidence of this quality being stronger in Gawain than in any of the other knights of the Round Table. He notes the words “courteous”, “courtesy” and “courteously” being used in reference to Arthur’s nephew 178 times in total, which is greater than the tally for all other knights in Arthurian literature.[6] In many romances, he is depicted as a model for this chivalric attribute.[29] In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, for example, Gawain receives the kisses of Lady Bertilak with discretion, at once not wanting to insult her by refusing her advances and not wanting to betray the hospitality of her husband.[30]

The loves of Sir Gawain[edit]Scholar M. Gaston Paris draws attention to the phenomenon that, since Gawain is known in multiple tales as “the Maidens’ Knight”, his name is thus attached to no woman in particular. He is the champion of all women, and through this reputation, he has avoided the name pairing seen in tales of Eric and Lancelot (the former being inextricably linked with Enide, the latter with Guinevere). He has, however, been connected to more than one woman in the course of Arthurian literature.[31] In the alliterative Middle-English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Sir Bertilak’s wife flirts with him. In the aforementioned The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle, he marries the cursed Ragnelle, and in giving her “sovereignty” in the relationship, lifts the spell laid upon her that had given her a hag-like appearance.[32] He is also associated with a vague supernatural figure in various tales. The hero of Le Bel Inconnu is the progeny of Gawain and a fairy called Blancemal, and in the Marvels of Rigomer, Gawain is rescued by the fay, Lorie.[29][33] In the German tale, Wizalois, the mother of his son is known as Florie, who is likely another version of the Lorie of Rigomer. In her earliest incarnations, Gawain’s love is either the princess or queen of the Other-world.[34]

As with many of the Arthurian romances and poems, there is a strong undertone of homoeroticism to many representations of the Gawain character. In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the sexual advances of Lady Bertilak allude to a potential sodomitical relationship with Sir Bertilak. Based on the bargain to give each other their respective daily gains, Gawain must give the kisses he receives from Lady Bertilak to Sir Bertilak. This allusion serves to reinforce chivalric ideals of religious, martial and courtly love codes, especially in masculine warrior culture, and shows the ways in which the masculine world can be subverted by female wiles. “[35] This possibility of sex between Gawain and Bertilak underscores the strength of male homosocial bonds, and the fact that sex never occurs reinforces ideals of the masculine chivalric code. [36]

Gawain features frequently in modern literature and media. Modern English depictions are heavily influenced by Malory, though characterizations of Gawain are inconsistent. Alfred Tennyson adapts episodes from Malory to present Gawain as a worldly and faithless knight in his Idylls of the King.[37][38][39] Similarly, T. H. White's novel The Once and Future King follows Malory, but presents Gawain as more churlish than Malory's torn and tragic portrayal.[40] In contrast, Thomas Berger's Arthur Rex portrays Gawaine as open-minded and introspective about his flaws, qualities that make him the Round Table's greatest knight.[41] Though he usually plays a supporting role, some works feature Gawain as the main character. Vera Chapman's The Green Knight and Anne Crompton's Gawain and Lady Green offer modern retellings of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.[42] Gwalchmai is the protagonist in Gillian Bradshaw's Celtic-tinged Hawk of May and its sequels.[43] An aged Gawain is one of the central characters in Kazuo Ishiguro's novel The Buried Giant.[44]

Film portrayals of Gawain, and the Arthurian legend in general, are heavily indebted to Malory; White's The Once and Future King also exerts a heavy influence. Gawain appears as a supporting character in films such as Knights of the Round Table (1953), Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) and Excalibur (1981), all of which draw on elements of his traditional characterizations.[45] Other films give Gawain a larger role. In the 1954 adaptation of Prince Valiant, he is a somewhat boorish, though noble and good-natured, foil for his squire and friend, Valiant.[46] He plays his traditional part in the 1963 film Sword of Lancelot, seeking revenge when Lancelot kills his unarmed brother Gareth, but ultimately coming to Lancelot's aid when he uncovers Mordred's responsibility.[47]Sir Gawain and the Green Knight has been adapted several times, including 1973's Gawain and the Green Knight and 1984's Sword of the Valiant, both directed by Stephen Weeks. Neither film was well reviewed and both deviate substantially from the source material.[48] A 1991 television adaptation by Thames Television, Gawain and the Green Knight, was both more faithful and better received.[49]

The character has appeared in a number of stage productions and operas, mostly interpretations of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Particularly notable among them is the 1991 opera Gawain with music by Harrison Birtwistle and a libretto by David Harsent.[50]

http://blog.sciencenet.cn/blog-847277-923754.html 此文来自科学网李胜文博客,转载请注明出处。

上一篇:美国新闻独立公证? 吹牛编故事?