陇山陇西郡

宁静纯我心 感得事物人 写朴实清新. 闲书闲话养闲心,闲笔闲写记闲人;人生无虞懂珍惜,以沫相濡字字真。谴责恶人的人会招致虐待

Proverbs 9:1-9 1Wisdom has built her house; she has set up its seven pillars. 2She has prepared her meat and mixed her wine; she has also set her table. 3She has sent out her servants, and she calls from the highest point of the city, 4"Let all who are simple come to my house!" To those who have no sense she says, 5"Come, eat my food and drink the wine I have mixed. 6Leave your simple ways and you will live; walk in the way of insight." 7Whoever corrects a mocker invites insults; whoever rebukes the wicked incurs abuse. 8Do not rebuke mockers or they will hate you; rebuke the wise and they will love you. 9Instruct the wise and they will be wiser still; teach the righteous and they will add to their learning.

“The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom, / and knowledge of the Holy One is understanding” (Proverbs 9:10). The entire chapter is devoted to the emphasis of seeking wisdom, avoiding folly, and finding this wisdom in the Lord.

Some commentators see the seven pillars as describing a traditional banquet pavilion. Understood this way, Wisdom’s call in Proverbs 9:5 is perfectly fitting: “Come, eat my food / and drink the wine I have mixed.”

Some ancient writings described the world as resting on seven pillars. If this was the author’s meaning, it is possible that “her house” in Proverbs 9:1 is parallel in some way with the world. However, this is an unlikely understanding of this particular proverb.

Some have theorized that the seven pillars of wisdom may refer to seven sections of Proverbs in the content previous to chapter 9.

In considering these interpretive options, it is most likely that “her house” and “seven pillars” both refer to a home that is in proper order, with the use of “seven” emphasizing its completeness and all-sufficiency. The following verses continue to describe other aspects of wisdom personified as a woman. She prepares a meal and invites people to attend to gain wisdom: “Leave your simple ways and you will live; / walk in the way of insight” (Proverbs 9:6). Wisdom has much to offer, and she invites everyone to come share her satisfying feast.

In contrast, verses 13–18 describe the way of folly, also personified as a woman. Folly is loud, seductive, and unwise (Proverbs 9:13). She seeks to deceive the simple-minded into stopping at her home to drink stolen water and secret bread (verses 16–17). Those who do find death instead of life (verse 18).

Seven Pillars of Wisdom

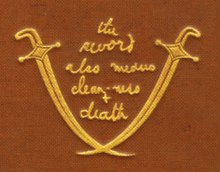

Tooling on the cover of the first public printing, showing twin scimitars and the legend: "the sword also means clean-ness + death" | |

| Author | T. E. Lawrence |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | private edition |

| Publication date | 1926 (completed 1922) |

| ISBN | 0-9546418-0-9 |

| OCLC | 54675462 |

Seven Pillars of Wisdom is the autobiographical account of the experiences of British soldier T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), while serving as a liaison officer with rebel forces during the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Turks of 1916 to 1918.

It was completed in February 1922, but first published in December 1926.[1]

Contents

Title[edit]

The title comes from the Book of Proverbs[2] (Proverbs 9:1): "Wisdom hath builded her house, she hath hewn out her seven pillars" (King James Version).[3] Prior to the First World War, Lawrence had begun work on a scholarly book about seven great cities of the Middle East,[4] to be titled Seven Pillars of Wisdom. When war broke out, it was still incomplete and Lawrence stated that he ultimately destroyed the manuscript although he remained keen on using his original title Seven Pillars of Wisdom for his later work. The book had to be rewritten three times, once following the loss of the manuscript on a train at Reading. From Seven Pillars, "...and then lost all but the Introduction and drafts of Books 9 and 10 at Reading Station, while changing trains. This was about Christmas, 1919." (p. 21)

Seven Pillars of Wisdom is an autobiographical account of his experiences during the Arab Revolt of 1916–18, when Lawrence was based in Wadi Rum (now a part of Jordan) as a member of the British Forces of North Africa. With the support of Emir Faisal and his tribesmen, he helped organise and carry out attacks on the Ottoman forces from Aqaba in the south to Damascus in the north. Many sites inside the Wadi Rum area have been named after Lawrence to attract tourists, although there is little or no evidence connecting him to any of these places, including the rock formations near the entrance now known as "The Seven Pillars".[5]

Speculation surrounds the book's dedication, a poem written by Lawrence and edited by Robert Graves, concerning whether it is to an individual or to the whole Arab race. It begins, "To S.A.", possibly meaning Selim Ahmed, a young Arab boy from Syria of whom Lawrence was very fond. Ahmed died, probably from typhus, aged 19, a few weeks before the offensive to liberate Damascus. Lawrence received the news of his death some days before he entered Damascus.[citation needed]

I loved you, so I drew these tides of

Men into my hands

And wrote my will across the

Sky in stars

To earn you freedom, the seven

Pillared worthy house,

That your eyes might be

Shining for me

When I came

Death seemed my servant on the

Road, 'til we were near

And saw you waiting:

When you smiled and in sorrowful

Envy he outran me

And took you apart:

Into his quietness

Love, the way-weary, groped to your body,

Our brief wage

Ours for the moment

Before Earth's soft hand explored your shape

And the blind

Worms grew fat upon

Your substance

Men prayed me that I set our work,

The inviolate house,

As a memory of you

But for fit monument I shattered it,

Unfinished: and now

The little things creep out to patch

Themselves hovels

In the marred shadow

Of your gift.

A variant last line of that first stanza—reading, "When we came"—appears in some editions; however, the 1922 Oxford text (considered the definitive version; see below) has "When I came". The poem originated as prose, submitted by letter to Graves, who edited the work heavily into its current form, rewriting an entire stanza and correcting the others.[citation needed]

Manuscripts and editions[edit]

Some Englishmen, of whom Kitchener was chief, believed that a rebellion of Arabs against Turks would enable England, while fighting Germany, simultaneously to defeat Turkey.

Their knowledge of the nature and power and country of the Arabic-speaking peoples made them think that the issue of such a rebellion would be happy: and indicated its character and method.

So they allowed it to begin...

— Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Introduction

Lawrence kept extensive notes throughout the course of his involvement in the Revolt. He began work on a clean narrative in the first half of 1919 while in Paris for the Peace Conference and, later that summer, while back in Egypt. By December 1919, he had a fair draft of most of the ten books that make up the Seven Pillars of Wisdom but lost it (except for the introduction and final two books) when he misplaced his briefcase while changing trains at Reading railway station.[6][7] National newspapers alerted the public to the loss of the "hero's manuscript", but to no avail; the draft remained lost. Lawrence refers to this version as "Text I" and says that had it been published, it would have been some 250,000 words in length.

In early 1920, Lawrence set about the daunting task of rewriting as much as he could remember of the first version. Working from memory alone (he had destroyed many of his wartime notes upon completion of the corresponding parts of Text I), he was able to complete this "Text II", 400,000 words long, in three months. Lawrence described this version as "hopelessly bad" in literary terms, but historically it was "substantially complete and accurate". This manuscript, titled by Lawrence "The Arab Revolt," is held by the Harry Ransom Center with a letter from Lawrence's brother authenticating it as the earliest surviving manuscript of what would become Seven Pillars of Wisdom.[8]

With Text II in front of him, Lawrence began working on a polished version ("Text III") in London, Jeddah, and Amman during 1921. Lawrence completed this text comprising 335,000 words in February 1922.

To eliminate any risk of losing the manuscript again, and to have copies that he could show privately to critics, he considered having the book typed out. However, he discovered that it would be cheaper to get the text typeset and printed on a proofing press at the Oxford Times printing works. Just eight copies were produced, of which six survive. In bibliographical terms the result was the first "edition" of Seven Pillars (because the text was reproduced on a printing press). In legal terms, however, these substitutes for a typescript were not "published". Lawrence retained ownership of all the copies and chose who was allowed to read them. The proof-printing became known as the "Oxford Text" of Seven Pillars. As a text it is unsatisfactory because Lawrence could not afford to have the proof corrected. It therefore contains innumerable transcription errors, and in places lines and even whole paragraphs are missing. He made corrections by hand in five of the copies and had them bound.[9] (In 2001, the last time one of these rough printings came on to the market, it fetched almost US$1 million at auction.) Instead of burning the manuscript, Lawrence presented it to the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

By mid-1922, Lawrence was in a state of severe mental turmoil: the psychological after-effects of war were taking their toll, as were his exhaustion from the literary endeavours of the past three years, his disillusionment with the settlement given to his Arab comrades-in-arms, and the burdens of being in the public eye as a perceived "national hero". It was at this time that he re-enlisted in the armed forces under an assumed name, for the most part in the Royal Air Force, as described in his book The Mint with the byline "by 352087 A/c Ross", with a period in the Royal Tank Corps as "Private Shaw". Concerned over his mental state and eager for his story to be read by a wider public, his friends persuaded him to produce an abridged version of Seven Pillars, to serve as both intellectual stimulation and a source of much-needed income. In his off-duty evenings, he set to trimming the 1922 text down to 250,000 words for a subscribers' edition.

The Subscribers' Edition – in a limited print run of about 200 copies, each with a unique, sumptuous, hand-crafted binding – was published in late 1926, with the subtitle A Triumph. It was printed in London by Roy Manning Pike and Herbert John Hodgson, with illustrations by Eric Kennington, Augustus John, Paul Nash, Blair Hughes-Stanton and his wife Gertrude Hermes. Copies occasionally become available in the antiquarian trade and can easily command prices of up to US$100,000. Unfortunately, each copy cost Lawrence three times the thirty guineas the subscribers had paid.[10]

The Subscribers' Edition was 25% shorter than the Oxford Text, but Lawrence did not abridge uniformly. The deletions from the early books are much less drastic than those of the later ones: for example, Book I lost 17% of its words and Book IV lost 21%, compared to 50% and 32% for Books VIII and IX. Critics differed in their opinions of the two editions: Robert Graves, E. M. Forster and George Bernard Shaw preferred the 1922 text (although, from a legal standpoint, they appreciated the removal of certain passages that could have been considered libellous, or at least indiscreet), while Edward Garnett preferred the 1926 version.

Literary merits aside, however, producing the Subscribers' Edition had left Lawrence facing bankruptcy. He was forced to undertake an even more stringent pruning to produce a version for sale to the general public: this was the 1927 Revolt in the Desert, a work of some 130,000 words: "an abridgement of an abridgement," remarked George Bernard Shaw, not without disdain. Nevertheless, it received wide acclaim by the public and critics alike, the vast majority of whom had never seen or read the unabridged Subscribers' Edition.

After the 1926 release of the Subscribers' Edition, Lawrence stated that no further issue of Seven Pillars would be made during his lifetime. Lawrence was killed in a motorcycle accident in May 1935, at the age of 46, and within weeks of his death, the 1926 abridgement was published for general circulation. The unabridged Oxford Text of 1922 was not published until 1997, when it appeared as a "best text" edited by Jeremy Wilson from the manuscript in the Bodleian Library and Lawrence's amended copy of the 1922 proof printing. Wilson made some further minor amendments in a new edition published in 2003.