TODAY is a big feast day for Scotland, Romania, Cyprus, the Greek port of Patras and for Christians in Istanbul; in 13 days' time, the same feast will be celebrated in places where the old church calendar is kept, such as Russia and Ukraine. And whenever it is observed, the annual feast day of Saint Andrew brings reminders that the first apostle of Jesus Christ, one of two fisherman brothers, can still create political waves.

Take Scotland. Andrew has been that country's official patron saint since 1320, and he was venerated there for centuries before that. The diagonal white cross of Saint Andrew was flying defiantly in Edinburgh today, although yesterday's helicopter crash in Glasgow cast a pall over the commemorations. Alex Salmond, head of the Scottish Nationalists, used the national holiday to stir patriotic feeling ahead of next year's independence ballot. Even his reaction to the helicopter crash mentioned the saint; he said today was a good moment to take pride in Scotland's resilience. Meanwhile David Cameron has hoisted the Scottish emblem over his prime-ministerial residence in London and issued a Saint Andrew's message with the opposite intention: to remind the Scots of how well they have done as Brits.

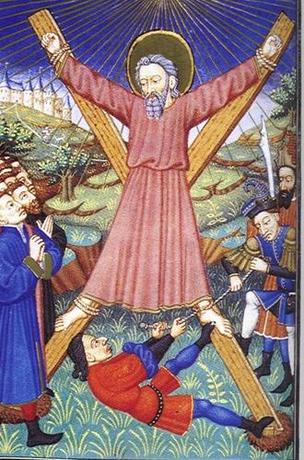

Move further east and competition over Andrew gets hotter. Who was he and where did he go? Written evidence about his life is fragmentary, but a church historian, Eusebius, says he preached among the Scythians, north of the Black Sea. Among Slavs, there is a strong tradition that he sailed up the river Dnieper and foresaw that Kiev would be a great Christian city. He is also credited with founding the first church on the shores of Bosporus (ie, modern Istanbul) and it is agreed that he met a martyr's death in Patras. He was stretched out on an X-shaped cross, so the tradition says, because he did not want to die on a cross exactly like the one associated with his master.

At the Patriarchate of Constantinople, an institution which sees Saint Andrew as its founder and protector, grand services were held today; guests included a Catholic cardinal who will have the chance to fine-tune plans for Orthodoxy's senior hierarch, Patriarch Bartholomew, to visit Rome next year. But Saint Andrew's legacy is also claimed by influential people in Moscow. The Apostle Andrew Fund, an NGO run by Russia's powerful railway boss, Vladimir Yakunin, arranged this summer for a wooden cross, believed to be the one on which the saint was martyred, to be brought from Patras to Russia, Ukraine and Belarus where national leaders, and vast crowds, venerated the holy object. It was an eye-catching affirmation of the bonds between the three Slavic Orthodox lands. At a time when Ukraine's geopolitical destiny is in the balance, the celebrations were a way of emphasising Ukraine's eastern links. But remember, there are followers of Andrew to the west of Ukraine too: Romania claims a special link with the saint, and his feast is an old folk festival in Poland.

On Cyprus, too, people feel a bond with the saint, and the name "Andreas" is common. A great monastery in the Turkish-held north of the island is said to mark a spot where the saint landed after his ship went off course; only recently, after years of bitter deadlock, has a deal been struck between the UN, the Greek-Cypriot church and a Turkish agency to carry out urgent repairs on the monastery. But the whereabouts of an ancient likeness of Saint Andrew, one of the mosaics hacked away from the wall of the nearby Kanakaria church in the 1970s, remain a mystery despite the recent restitution to Cyprus of some important pieces of stolen art.

For all his ubiquity, the biblical Andrew is a shadowy figure. In one of a handful of scriptural references, he is the apostle who tells Jesus that five loaves and two fishes won't feed 5,000 people; a miracle soon proves otherwise. Like other widely honoured saints, Andrew himself defies the laws of finitude by appealing to so many people in so many places.