A very well written review. As an American and having just finished reading, “The End of Normal”, I am surprisingly more sympathetic to the potential of a Marxian steady-state economic policy for the 21st Century. I would say that the unmentioned undercurrent of Dr. Galbraith’s thesis appears to be Malthusian in nature as an anecdote to the current Darwinian-Capitalistic environment of today. A thought occurred to me while I was reading the book; What if the missing variable to the magic equation used by economists to formulate success is food itself. We take it for granted that the industrial revolution has solved the problem of availability of foodstuffs but what if in a very near future when the people-o-meter reads 10 billion, As was hinted by Dr. Galbraith, that the old environmental, fixed resources of arable land and water and human inability to control weather problems which have plagued farmers since the beginning of agriculture shows up in the 21st Century with a vengeance? I would say as a pessimist that when that day comes, and I am positive it will, a concerted Marxist approach is the only way to save the human race from annihilation.

2022 (857)

2023 (2384)

2024 (1325)

正常的终结, 大危机和增长的未来

The End of Normal, The Great Crisis and the Future of Growth

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-End-of-Normal/James-K-Galbraith/9781451644944

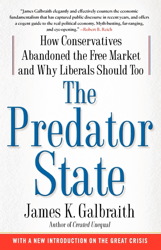

掠夺者国家

这是当代最受尊敬的经济思想家和作家之一对经济增长的历史和未来的精彩论述。

自 2008 年大危机以来的几年里,经济增长缓慢、失业率高企、房价下跌、长期赤字、欧洲灾难加剧——以及两种错误解决方案之间的陈旧争论,一边是“紧缩”,另一边是“刺激”。到目前为止,双方和几乎所有对这场危机的分析都理所当然地认为,从 20 世纪 50 年代初到 2000 年的经济增长(只被困难重重的 20 世纪 70 年代所中断)代表着正常的表现。从这个角度来看,这场危机是一种中断,是由糟糕的政策或糟糕的人造成的,如果原因得到纠正,就可以期待全面复苏。

《正常的终结》挑战了这种观点。加尔布雷斯从宏观角度看待这场危机,他认为 20 世纪 70 年代已经结束了轻松增长的时代。20 世纪 80 年代和 90 年代只出现了不平衡的增长,国家内部和国家之间的不平等加剧。21 世纪甚至连这种情况都结束了——尽管人们拼命努力通过减税、战争支出和金融放松管制来保持增长。当危机最终来临时,刺激和自动稳定能够为经济崩溃奠定基础。但它们无法带来高增长和充分就业的回归。在《正常的终结》中,“加尔布雷思将他的悲观主义置于一个引人入胜、可信的框架中。他的观点值得所有经济学家和政治领域严肃金融人士的关注”(《出版商周刊》,星级评论)。

书 评 评论者:汉斯·德斯潘

汉斯·德斯潘是马萨诸塞州尼科尔斯学院的经济学教授兼系主任。他鼓励您来信:hans.despain@nichols.edu

詹姆斯·K·加尔布雷思最近出版的《正常的终结》是政治经济学领域的一项重大成就,它对经济学实践和公共政策进行了哲学批判,对全球垄断金融资本主义进行了全面而全面的解释。

加尔布雷思的主要关注点有三个。首先,加尔布雷思解释了美国和全球企业资本主义体系的矛盾及其深层的金融弱点。其次,加尔布雷思对稳定的“正常”资本主义概念进行了批判。根据加尔布雷思的说法,“正常”稳定概念使主流经济学家无法预见 2007 年之前金融安排的根本不稳定。第三,加尔布雷思认为,左右两派都未能理解当代公司金融资本主义的制度结构转变。[我的《正常的终结》是高级电子版,因此为了避免页面错位,我提供了章节引文]。

加尔布雷思认为,苏联体制崩溃的原因之一是社会理论家对该体制的理解不够。同样,2007-8 年的金融崩溃令大多数经济学家和政治家如此意外的原因之一是人们对美国公司资本主义的理解不够(结语)。

主要的理论障碍是教条地坚持“正常”的经济表现,以及“淡水经济学家”(即亲市场经济学家,其中许多人居住在美国大湖地区)的信念,即“正常”是通过市场价格调整实现的,或“咸水经济学家”(即亲市场凯恩斯主义经济学家,其中许多人居住在美国沿海地区)的信念,即“正常”是通过经济管理、市场调整和适当的公共政策实现的(第 4 章)。

加尔布雷思认为这两种信念都是虚幻的。根据加尔布雷思的说法,2007-8 年的金融危机是一次“决定性的”制度转变。淡水经济学家的模型从未适用于资本主义的现实,而咸水经济学家的模型不再适用。 “[经济崩溃] 之后没有出现战后正常模式的正常商业周期好转,这并不令人意外”(第 9 章)。凯恩斯主义刺激无法解决当代企业资本主义的问题。“凯恩斯主义复兴的制度、基础设施、资源基础和心理基础已不复存在”(第 9 章)。[有关更多凯恩斯主义失败的案例,请参阅第 8、9 和 14 章]

正确的比喻

加尔布雷斯认为,发动机的行为就是发动机的行为(第 6 章)。发动机在接近极限时才能达到最佳性能。如果超出极限,发动机就会过热、烧坏或熔化,在这种情况下,必须重建发动机才能重新启动。我们的经济汽车“遭遇了传动故障。熔化了。发动机中再多的 [凯恩斯主义] 汽油也无法让它运转”(第 9 章)。通过在现有的破损系统上投入更多资金,无法恢复就业。有了更多的钱,消费者就会偿还债务,企业会投资于节省更多劳动力的技术,银行也会设置超额准备金。凯恩斯主义的刺激措施不再有效(第 8 章)。“金融系统更像是核反应堆,而不是汽车。”我们需要清理和重建。

尽管“常态”(或系统平衡或均衡)的概念“非常强烈”,但结构性制度转变已使这些概念既过时(序言),又“危险”(第 9 章)。在战后经济中,经济增长变得可取、可预期、永久和“正常”。资本主义“黄金时代”的争论关注的是需要多少政府干预才能实现“正常”经济增长(第 1 章)。

到 20 世纪 70 年代,几条“蛇”进入了“增长花园”。越南战争标志着国际制度偏离布雷顿森林协议。由于“国内石油峰值”生产和石油卡特尔组织 OPEC 的崛起,石油价格大幅上涨。然后是 20 世纪 70 年代的深度衰退。加尔布雷思认为,这些都是真正的地理资源和制度变革的预兆,而不仅仅是暂时的“冲击”或“管理不善和政策失误”(第 2 章)。

国际政治经济和美国企业资本主义的制度生理发生了变化。加尔布雷思试图向受过教育的大众听众阐明这一点,但低估了他所提出的深刻的哲学论点。这是一种本体论批判。加尔布雷思认为,无论是新古典主义、凯恩斯主义还是马克思主义的经济学模型,都未能充分理解新制度秩序的爆炸性和不稳定性(第 4 章)。保守的市场原教旨主义理论将主导经济理论和政策(第 3 章);他们从根本上误解了当代企业资本主义的本体论。

市场原教旨主义占主导地位,很大程度上是由于凯恩斯主义政策未能管理该体系。但与主流理论相反,凯恩斯主义的失败并没有带来“大缓和”和危机的结束(第 3 章)。相反,全球化、金融化、苏联体制的垮台、中国的崛起、伊朗革命以及巨大的系统性不平等都表明这个体系高度不稳定。

加尔布雷思认为,新新工业国家(我的术语,指的是加尔布雷思的制度发展,远离约翰·肯尼斯·加尔布雷思 1967 年的新工业国家概念,但深深植根于这一概念)必须被理解为主要是金融的。加尔布雷思对金融化的解释很少,但他却认为已故的海曼·明斯基的分析很好地抓住了这个新金融体系的本质。明斯基以他的比喻而闻名:“稳定产生不稳定”。 “明斯基思想的激进之处在于,它始于金融体系,终于金融体系,从未超越金融体系”(第 5 章)。在明斯基的模型中,政府“金融监管”发挥着明确而具体的作用(第 5 章)。加尔布雷思没有提到明斯基进一步强烈支持财政和就业政策以消除贫困(明斯基 2013 年)。尽管如此,加尔布雷思的强项是,任何严肃的分析诊断都必须接受新新工业国家的激进金融性质。正如明斯基(2013 年,177)所言,资本主义公司制度“存在缺陷”,因为“市场机制无法实现和维持充分就业”,而且它“天生(在金融上)目光短浅,需要政府才能拥有的长远眼光不断补充”。

《正常的终结》论证的核心是构成第二部分“增长终结的四骑士”的四章。如果新新工业国家始于金融化的制度表现,那么加尔布雷思认为,金融化不仅会产生巨大的不平等和不稳定(见 Galbraith 2012),还会为巨大的欺诈行为创造机会。加尔布雷思认为,我们必须“明确指出,大金融危机的根源在于一场巨大的金融欺诈计划”(第 9 章)。马克思主义者倾向于低估欺诈的作用,以强调无论有没有欺诈,系统性不稳定。加尔布雷思认为这是一个错误。他有一个重要的观点。用更马克思的语言来说,欺诈

是一种权力关系,允许在生产过程之前、期间和之后进行超级剥削或剥削。

许多经济学家认为技术是“拯救我们摆脱经济停滞的最大希望”(第 8 章)。加尔布雷斯认为这不太可能。这是因为技术创新往往是节省劳动力的技术变革,而不是新的工作和消费模式。“新技术的明显结果是失业”(第 8 章)。更糟糕的是,技术变革不仅取代了工人,而且破坏了商业活动。廉价燃料、与之相辅相成的工业技术、家庭收入消费、消费、消费以及推动这一切的金融基础等“重大偶然事件” “发生过一次。[然而]没有令人信服的理由期望[它]会再次发生”(第 8 章)。技术变革现在对就业、消费和投资的拖累与当时的促进作用一样大。

加尔布雷思进一步认为,国际力量平衡可能有利于美国,但不利于资本主义(大型企业主导)贸易。军事产生的秩序不再能维持。全球经济停滞和数百个国家普遍存在的欠发达“无法通过军事手段解决”。因此,军事维持了全球秩序,而“我们所知道的”战争似乎已经结束。“在现代条件下,战争和军事全球管理的游戏是没有利润的”(第 7 章)。

加尔布雷思论点的基本要素是四骑士中的第一个。具体来说,资源成本及其产生的全球动态(与金融化相结合)正在产生巨大的经济不稳定和政治反复无常。加尔布雷思认为,我们面临的通胀威胁不是来自预算赤字或高就业率,而是来自能源价格和成本。中央银行和国际经济机构根本没有能力和能力有效地管理这些“大规模杀伤性武器”(WMD)及其造成的不稳定和危机。

基本论点是,全球大型企业资本主义存在“高固定”成本结构,增加了石油等经济资源的需求和价格。每当总需求增加(例如来自中国)时,资源价格就会上涨,金融垄断和金融投机开始预期能源价格上涨,从而进一步提高资源和能源的价格。简而言之,需求的增加(来自家庭、企业或政府)会刺激金融投机,提高能源价格和生产成本。因此,能源价格通过增加生产成本和降低企业利润(第 6 章)对增长和充分就业起到了“扼杀”作用。用更马克思的语言来说:一个简单的垄断-金融资本矛盾。这并不一定会阻止价格上涨,企业垄断业务和垄断金融活动可能会在能源价格高企的情况下继续进行,从而进一步助长投机行为。这会导致价格连续飙升,投机泡沫不可避免地破裂,造成“鞭笞”效应(第 14 章)和严重的不稳定性和不确定性(第 6 章)。

政策前进的方向很少被理解(第 10 章),因为金融化的制度转变(第 5 章)、资源成本和“扼杀”和“鞭笞效应”(第 6 章),以及国际政治和经济机构的巨大转变、军事强制国际秩序的无能(第 7 章)、现代技术创新的劳动力节约和商业不稳定性质(第 8 章)以及欺诈与金融化的共生关系(第 9 章)尚未被理解为在结构上体现新新工业国家的整体。

“疯狂”的经济推理误解了危机,并开出了注定会失败的政策(例如紧缩政策)(第 11 章)。欧洲国家停滞不前,原因是货币制度框架僵化,缺乏有效的内置机构在经济衰退期间“自动”重新分配。然而,重要的是要明白欧洲正在应对同样的“一场”危机(加尔布雷斯认为,这场危机是美国造成的)。PIGS 的首字母缩略词通常代表“葡萄牙、冰岛、希腊、西班牙”,更确切的意思是“黄金高盛的主要煽动者”(第 13 章,注 1)。然而,欧洲国家的制度结构非常不同,这往往会削弱政策反应(第 13 章)。

凯恩斯主义政策或刺激性支出最终不会有效,因为本书第二部分的“四骑士”以及现代金融不再是增长的动力(第 14 章)。相反,我们可以遵循 Costas Lapavitsas (2013) 的观点,即银行已经成为“金融掠夺”的机构,

过度剥削的深层制度根源(另见 Despain 2014)。

Galbraith 认为我们正在进入一个缓慢增长的时期。唯一的出路是经济规划(结语)。目前,“规划”是由企业为了自己的利益而进行的。规划可以通过由公共部门实施,为更多公民和社区提供更大的利益(Galbraith 2014 深深植根于 Galbraith 1973 和 1967)。Galbraith 认为,公共赤字不会限制计划经济中的支出(第 12、5 章)。可以管理利率以限制赤字的增长(第 12 章)。

Galbraith 的政策处方包括支持面向公共目的的公共银行。他坚持保护和扩大社会保险计划的重要性,包括提前退休以腾出空间给年轻工人。他支持保障(生活)个人收入(也曾得到极端保守的经济学家米尔顿·弗里德曼的支持)。他强调“大幅提高最低工资”的紧迫性,这确立了实际生活工资,并强调了增加国民收入中流向劳动力的份额、减少国民收入中流向资本的份额的税收政策。加尔布雷思进一步坚持对掠夺性寻租活动征收高额税款。

我们当然可以在原则上支持这些政策。但明显缺乏的是,人们认识到资本主义不是替代方案:CINA(Despain 2013a),加尔布雷思当然知道,但完全忽略了现有的解放替代方案:EASE(Despain 2013a)。此外,还有“务实”的就业政策,为忍受剥削性企业资本关系并走向 EASE 的个人提供工作和尊严(参见 Despain 2012,作为对加尔布雷思政策建议的重要补充而撰写)。

加尔布雷思对“马克思主义观点”的批评是愚钝和误导的。加尔布雷思认为,“马克思-巴兰-斯威齐-鲍尔斯-金蒂斯的立场(奇怪的混合!)是资本主义是不稳定的,危机不可避免。这一主题将危机的风险根植于资本、垄断资本和金融资本的特定属性。它开放甚至鼓励人们认为,不同的社会制度可能不那么不稳定,也不容易发生危机”,根据加尔布雷思的说法,这是一个历史弱点(第 4 章)。如果这里的论点是马克思主义政治经济学通常低估了制度,我会承认这一点。然而,暗示巴兰和斯威齐、鲍尔斯和金蒂斯以及马克思低估了制度,这很奇怪。

加尔布雷思对《每月评论》传统的批评不仅奇怪,而且具有误导性。加尔布雷思直接引用了《每月评论》理论家约翰·福斯特和罗伯特·麦克切斯尼(2012)以及德斯潘(2013b)的观点,他断言:“严格来说,他们所认定的危机并不是金融危机”(第 4 章)。加尔布雷思在这一传统的其他观点上完全错了,“马克思主义者的问题在于,金融本身并不能解释任何事情。在他们看来,金融的作用基本上是表面文章”(第 4 章)。福斯特和麦克切斯尼(以及他们之前的巴兰和斯威齐)对明斯基的见解表示了极大的钦佩,并吸收了明斯基的见解。对于这些理论家来说,金融化是经济停滞和垄断资本的表现,但一旦出现,金融就会拥有自己的生命和活力。福斯特和麦克切斯尼的优势在于,金融化理论认为其根植于社会生产关系,而不是从不涉足金融之外(第 5 章),而不是明斯基的优势。

加尔布雷思缺乏对金融化及其对家庭、非金融企业、金融企业、公共政府、教育机构和机构间辩证关系(后者是 Lapavitsas 2013 的主题)的影响的制度分析。这里的文献非常丰富,其中大部分都深深植根于马克思主义政治经济学。然而,加尔布雷思没有提供任何引文,而是严格依赖对明斯基的引用。

加尔布雷思的《正常的终结》将因其深刻的批评、原创的理论见解、政策导向,尤其是其语气和目的的紧迫性而受到高度推崇和赞誉数十年。

2014 年 8 月 10 日

参考文献

Despain, Hans G. 2014 评论 Costas Lapavitsas 所著的《不生产而获利:金融如何剥削我们所有人》,《马克思与哲学书评》,2 月 13 日。https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviewofbooks/reviews/2014/956

Despain, Hans G. 2013a 这是愚蠢的制度:结构性危机和对资本主义替代方案的需求《每月评论》65(6):39-44 http://monthlyreview.org/2013/11/01/its-the-system-stupid/

Despain, Hans G. 2013b 评论 John Bellamy Foster 所著的《无休止的危机:垄断金融资本如何从美国到中国制造停滞和动荡》

和 Robert McChesney,1 月 30 日 https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviewofbooks/reviews/2013/694

Despain, Hans G. 2012 务实就业政策后凯恩斯主义经济学论坛 11 月 16 日 http://pke-forum.com/2012/11/16/pragmatic-employment-policy/

Foster, John Bellamy 和 McChesney, Robert W. 2012 无休止的危机:垄断金融资本如何从美国到中国造成停滞和动荡 纽约:每月评论出版社。

Galbraith, James K. 2012 不平等和不稳定:大危机前世界经济研究 牛津大学出版社,牛津。

Galbraith, John Kenneth。1973 经济学与公共目的 波士顿:霍顿·米夫林公司。

Galbraith, John Kenneth。 1967 [2007] 工业国家普林斯顿和牛津:普林斯顿大学出版社。

Lapavitsas,Costas。2013 不生产而获利:金融如何剥削我们所有人伦敦和纽约:Verso。

Minsky,Hyman P. 2013 消除贫困:工作,而不是福利 Annandale-on-Hudson,NY:Levy Economics Institute。

URL:https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviews/7923_the-end-of-normal-review-by-hans-g-despain/

本评论根据 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License 许可

一条评论

Goofus 说: 2014 年 12 月 25 日下午 2:07

一篇写得很好的评论。作为一名美国人,我刚刚读完《正常的终结》,我惊讶地发现,马克思主义稳定经济政策在 21 世纪的潜力更大。我想说,加尔布雷斯博士论文中未提及的暗流似乎是马尔萨斯主义的,是当今达尔文资本主义环境的一个轶事。我在阅读这本书时想到:如果经济学家用来制定成功的神奇方程式中缺少的变量是食物本身,那会怎样?我们理所当然地认为工业革命已经解决了粮食供应问题,但如果在不久的将来,当人口计量表读数达到 100 亿时,正如加尔布雷斯博士所暗示的那样,自农业开始以来一直困扰农民的旧环境、固定的耕地和水资源以及人类无法控制的天气问题在 21 世纪以复仇的方式出现,那会怎样?作为一个悲观主义者,我想说,当那一天到来时——我确信它一定会到来——采取协调一致的马克思主义方法是拯救人类免于灭绝的唯一途径。

The End of Normal

The Great Crisis and the Future of Growth

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-End-of-Normal/James-K-Galbraith/9781451644944

We and our third party partners use cookies, pixels, and other tracking technologies to operate the site, enhance site navigation, analyze site usage and performance, and assist in our marketing efforts such as to display personalized content, including ads. Please review ourPrivacy Policy which applies to your use of this site and make your cookie choices below.

From one of the most respected economic thinkers and writers of our time, a brilliant argument about the history and future of economic growth.

The years since the Great Crisis of 2008 have seen slow growth, high unemployment, falling home values, chronic deficits, a deepening disaster in Europe—and a stale argument between two false solutions, “austerity” on one side and “stimulus” on the other. Both sides and practically all analyses of the crisis so far take for granted that the economic growth from the early 1950s until 2000—interrupted only by the troubled 1970s—represented a normal performance. From this perspective, the crisis was an interruption, caused by bad policy or bad people, and full recovery is to be expected if the cause is corrected.

The End of Normal challenges this view. Placing the crisis in perspective, Galbraith argues that the 1970s already ended the age of easy growth. The 1980s and 1990s saw only uneven growth, with rising inequality within and between countries. And the 2000s saw the end even of that—despite frantic efforts to keep growth going with tax cuts, war spending, and financial deregulation. When the crisis finally came, stimulus and automatic stabilization were able to place a floor under economic collapse. But they are not able to bring about a return to high growth and full employment. In The End of Normal, “Galbraith puts his pessimism into an engaging, plausible frame. His contentions deserve the attention of all economists and serious financial minds across the political spectrum” (Publishers Weekly, starred review).

Reviewed by Hans G Despain

About the reviewer

Hans G Despain is Professor of Economics and Department Chair at Nichols College, Massachusetts. He encourages your correspondence: hans.despain@nichols.edu

James K Galbraith's The End of Normal, recently published, is a spectacular achievement in political economy generally, as a philosophical critique of the practice of economics and public policy in particular, and for its comprehensive and totalizing explanation of global monopoly-finance capitalism.

Galbraith’s primary focuses are threefold. Foremost, Galbraith explains the contradictions of the American and global corporate capitalistic system and its deep financial weaknesses. Second, Galbraith develops a critique of the conception of a stable “normal” capitalism. The conception of a “normal” stability according to Galbraith precluded the mainstream economists from foreseeing the radical instability of the financial arrangements prior to 2007. Third, Galbraith contends that the right and left have failed to understand the institutional structural shifts of contemporary corporate-finance capitalism. [My copy of The End of Normal is an advanced electronic copy, thus to avoid page misalignment, I provide chapter citations].

Galbraith contends one reason the Soviet system collapsed was that the system was insufficiently understood by social theorists. Likewise, one reason that the financial collapse of 2007-8 was such a surprise to the majority of economists and politicians is that American corporate capitalism is insufficiently understood (Epilogue).

The primary theoretical blockage is the dogmatic commitment to a sense of “normal” economic performance and the belief by “freshwater economists” (i.e., pro-market economists, many of whom are located around the U.S. great lakes region) that “normality” is achieved by market adjustment of prices, or “saltwater economists” (i.e. pro-market Keynesian-inspired economists, many of whom are located on the ocean coasts of the U.S.) who believe “normality” is achieved with economic management, market adjustment, and proper public policy (Chapter 4).

Galbraith contends that both beliefs are illusionary. The financial collapse of 2007-8 was, according to Galbraith, a “definitive” institutional shift. The models of freshwater economists never applied to the reality of capitalism, and the models of saltwater economists no longer apply. “That [the collapse] was not followed by a normal business cycle upturn on the model of postwar normality should not come as a surprise” (Chapter 9). Keynesian stimulus cannot cure the problems of contemporary corporate capitalism. “The institutional, infrastructure, resource basis, and psychological foundation for a Keynesian revival no longer exist” (Chapter 9). [for more Keynesian failures see Chapters 8, 9 and 14]

The proper metaphor according to Galbraith is the behavior of an engine (Chapter 6). Peak performance is achieved near the limits of an engine. Pushed past their limits, engines overheat, burn out, or melt down, in which case they must be rebuilt before they can be restarted. Our economic car “has suffered a transmission failure. A meltdown. More [Keynesian] gas in the engine will not make it go” (Chapter 9). Jobs cannot be retrieved by spending more money on the existing broken systems. Given more money, consumers pay down debt, businesses invest in technologies that save yet more labor, and banks have been setting on excess reserves. Keynesian stimulus is no longer effective (Chapter 8). “And a financial system is more like a nuclear reactor than it is like a car.” We need to clean up and rebuild.

In spite of the “very strong” notion of “normality” (or systemic balance, or equilibrium), structural institutional shifts have made such notions both obsolete (Prologue) and “dangerous” (Chapter 9). In the post-war economy economic growth became desirable, expected, perpetual, and “normal”. The debates during the “Golden Age” of capitalism were concerned with how much government intervention was needed to achieve “normal” economic growth (Chapter 1).

By the 1970s several “snakes” entered the “growth garden.” The Vietnam War would come to mark an institutional international shift away from the Bretton Woods agreement. The price of oil would rise significantly due to “domestic peak oil” production and the rise of the oil cartel OPEC. Then rose the deep recession of the 1970s. Galbraith contends these are harbingers of real geographical resource and institutional transformations, not merely temporary “shocks,” or “bad management, and policy mistakes” (Chapter 2).

The institutional physiology of the international political economy and American corporate capitalism shifted. Galbraith’s attempt to articulate this to an educated popular audience understates the profound philosophical argument he is lodging. This is an ontological critique. Models of economics, whether they be neo-classical, Keynesian, or Marxian have failed, according to Galbraith, to fully understand the explosive and unstable nature of the new institutional order (Chapter 4). Conservative market fundamentalist theories would come to dominate economic theory and policy (Chapter 3); they fundamentally misunderstand the ontology of contemporary corporate capitalism.

Market fundamentalism predominates largely due to the failures of Keynesian policy to manage the system. But the failures of Keynesianism did not, contrary to mainstream theories, usher in a “great moderation” and an end of crisis (Chapter 3). Instead, globalization, financialization, the fall of the Soviet system, the rise of China, the Iranian revolution, and the massive systemic-generated inequalities were indications of a highly precarious and unstable system.

Galbraith contends that the New New Industrial State (my term, in reference to Galbraith’s institutional development away from, but deeply rooted in, the notion of the New Industrial State of John Kenneth Galbraith 1967) must be understood as primarily financial. Galbraith explains very little of financialization, but instead contends the late Hyman Minsky’s analysis well captures the essence of this new financial system. Minsky is quite (in)famous for his metaphor: “stability generates instability”. “[W]hat is radical about Minsky’s thought is that it begins and ends within the financial system and never ventures outside of it” (Chapter 5). In Minsky’s model there is a specific and clear role of government “financial regulation” (Chapter 5). Galbraith fails to mention that Minsky further strongly supported fiscal and employment policy to end poverty (Minsky 2013). Nonetheless Galbraith’s strong point is that any serious analytical diagnoses must come to terms with the radical financial nature of the New New Industrial State. As Minsky (2013, 177) argued, the capitalist corporate system is “flawed” in that within it “the market mechanisms cannot achieve and maintain full employment” and it is “inherently [financially] myopic and needs to be permanently supplemented by the long view that government alone can have.”

The heart of the argument in The End of Normal is the four chapters constituting Part Two “The Four Horseman of the End of Growth.” If the New New Industrial State begins with the institutional manifestation of financialization, Galbraith contends that not only does financialization generate massive inequality and instability (see Galbraith 2012), but generates opportunities for colossal fraud. Galbraith contends we must “stipulate that the Great Financial Crisis was rooted in a vast scheme of financial fraud” (Chapter 9). Marxists tend to underplay the role of fraud so as to emphasis the systemic instability with or without fraud. Galbraith maintains this to be a mistake. He has an important point. In more Marxian language, fraud is a type of power-relation and allows superexploitation, or exploitation before, during, and after the production process.

Many economists believe technology stands “as our best hope for rescue from economic stagnation” (Chapter 8). Galbraith argues this is very unlikely. This is because technological innovation has tended to be labor-saving technical change and not new modes of jobs and consumption. “The plain result of the new technology is unemployment” (Chapter 8). Worse still, the technological shifts not only displace workers but destabilize business activity. “The great contingent events” of cheap fuel, along with the industrial technology to complement it, household income to consume, consume, consume, and the financial basis to propel it all “happened once. [However] there is no compelling reason to expect [it] to happen again” (Chapter 8). Technological change is now as much a drag on employment, consumption and investment as it was then a boost.

Galbraith further contends that the international balance of power may favor the U.S., but it does not favor capitalistic (megacorporate-dominated) trade. Military generated order can longer be maintained. The global economic stagnation and ubiquitous underdevelopment of hundreds of countries “have no remedy by military means.” Thus, the military maintained global order and war as ‘we knew it’ appear to have ended. “Under modern conditions there is no profit in the game” of war and military global management (Chapter 7).

The essential element of Galbraith’s argument is the first of the four “horseman.” Specifically, resource costs and the global dynamic they generate (in conjunction with financialization) are generating tremendous economic instability and political capriciousness. Galbraith maintains the inflation threat we face does not come from budget deficits or high employment, but from energy prices and costs. Central banks and international economic institutions simply do not have the capacity and competence to effectively manage these ‘wonders of mass destruction’ (WMDs) and instability and crises they generate.

The essential argument is that there is a “high-fixed” cost structure in global mega-corporate capitalism, increasing the demand and prices of economic resources such as oil. Each time there is an increase in aggregate demand (e.g., from China) the prices of resources increase, financial-monopolies and financial speculation begins to anticipate the rise in energy prices, increasing prices of resources and energy still more. In short, an increase in demand (from households, businesses, or governments), excites financial speculation, raises energy prices and production costs. Thus, energy prices are functioning as a “choke-chain” on growth and full-employment by increasing the costs of producing and decreasing business profits (Chapter 6). In more Marxian language: a simple monopoly-finance capital contradiction. This does not necessarily stop prices from rising, corporate monopoly business and monopoly financial activity may proceed in spite of high energy prices, fueling speculation even further. This generates a sequence of spiking prices and the inevitable bursting of the speculation bubble, causing a “whiplash” effect (Chapter 14) and significant instability and uncertainty (Chapter 6).

The policy-way forward has been little understood (Chapter 10), because the institutional shifts of financialization (Chapter 5), resource costs and the “choke-chain” and “whiplash effects” (Chapter 6), along with the tremendous shifts in international political and economic institutions, the inability of military-forced international order (Chapter 7), the labor-saving and business destabilizing nature of modern technological innovation (Chapter 8), and the symbiotic relationship between fraud and financialization (Chapter 9) have not been appreciated as a totality that has structurally manifested a New New Industrial State.

“Crackpot” economic reasoning has misunderstood the crisis and prescribes policy (e.g. austerity) that is sure to fail (Chapter 11). European countries stagnate due to a rigid monetary institutional framework and lack of effective built-in institutions to “automatically” redistribute during a recession. However, it is important to understand Europe is dealing with same “one” crisis (generated in the U.S. Galbraith contends). The PIGS acronym, usually standing for “Portugal, Iceland, Greece, Spain” is more true in meaning as “Principal Instigator Gold Sachs” (Chapter 13, note 1). However, European nations have very different institutional structures that have tended to weaken policy responses (Chapter 13).

Keynesian policy or stimulant spending ultimately will not be effective because of the “four horseman” of Part II of the book and because modern finance is no longer a motor of growth (Chapter 14). Instead we can follow Costas Lapavitsas’s (2013) argument, that banks have become institutions of “financial expropriation” and the deep institutional source of superexploitation (see also Despain 2014).

Galbraith contends we are entering a period of slow growth. The only way forward is economic planning (Epilogue). Currently the “planning” is being performed by corporations for their own enrichment. Planning can be aimed to provide greater benefits to more citizens and communities by being carried out by the public sector (Galbraith 2014 is deeply rooted in Galbraith 1973 and 1967). Galbraith argues public deficits are no constraint on spending in a planned-economy (Chapters 12, 5). Interest rates can be managed to put an upper limit on the growth of deficits (Chapter 12).

Galbraith’s policy prescriptions include support for public banks geared towards public purposes. He insists on the importance of the protection and extension of social insurance programs, including early retirement to make room for young workers. He supports a guaranteed (living) personal income (also once supported by ultra-conservative economist Milton Friedman). He stresses the urgency of “a large increase in minimum wage,” which establishes a real living wage, and tax policies that increase the share of national income going to labor and decreases the share of national income going to capital. Galbraith further insists on a large tax upon predatory rent-seeking activities.

We can certainly support these policies in principle. But conspicuously absent is the recognition that capitalism is no alternative: CINA (Despain 2013a) and Galbraith is certainly aware of, but completely ignores the Existing Alternatives to Start Emancipation: EASE (Despain 2013a). Moreover, there are “pragmatic” employment policies to provide work and dignity to individuals enduring exploitive corporate capital relations and bridging toward EASE (see Despain 2012, written as a critical complement to Galbraith’s policy proposals).

Galbraith’s critique of “The Marxian View” is obtuse and misleading. Galbraith contends that the “Marx-Baran-Sweezy-Bowles-Gintis position [strange conflation!] has been that capitalism is unstable and crisis inevitable. This theme roots the risk of crisis in specific properties of capital, monopoly capital and finance capital. It leaves open, and even encourages, the thought that a different social system might be less unstable and less prone to crisis,” which according to Galbraith is a historical weakness (Chapter 4). If the argument here is Marxian political economy has generally underemphasized institutions, I would concede the point. However, to suggest that Baran and Sweezy, Bowles and Gintis, and Marx underemphasize institutions is strange.

Galbraith’s critique of the Monthly Review tradition is not only strange but misleading. In direct reference to Monthly Review theorists John Foster and Robert McChesney (2012) and also to Despain (2013b), Galbraith asserts: “the crisis that they identify is not, strictly speaking, a financial crisis” (Chapter 4). Elsewhere on this tradition, Galbraith is simply wrong, “The problem for Marxians is that finance explains nothing on its own. In their vision, the role of finance is substantially cosmetic” (Chapter 4). Foster and McChesney (and Baran and Sweezy before them) express the utmost admiration for, and have incorporated the insights of, Minsky. For these theorists financialization is a manifestation of economic stagnation and monopoly capital, but once emergent finance takes on a life and dynamic of its own. It is to Foster’s and McChesney’s, and not Minsky’s, advantage that financialization is theorized to be rooted in social relations of production, rather than never venturing outside of finance (Chapter 5).

Galbraith lacks his own institutional analysis of financialization and the effects it has on households, non-financial enterprises, financial enterprises, public governments, educational institutions, and dialectical relationships between institutions (the latter is the subject of Lapavitsas 2013). The literature here is vast, and the bulk of it is deeply rooted in Marxian political economy. Yet Galbraith provides not one citation, strictly relying on reference to Minsky.

Galbraith’s The End of Normal will be highly esteemed and celebrated for many decades for its penetrating critiques, original theoretical insights, policy-minded orientation, and especially for the urgency of his tone and purpose.

10 August 2014

References

-

Despain, Hans G. 2014 Review of Profiting without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All by Costas Lapavitsas,” Marx and Philosophy Review of Books, February 13. https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviewofbooks/reviews/2014/956

-

Despain, Hans G. 2013a It’s the System Stupid: Structural Crises and the Need for Alternatives to Capitalism Monthly Review 65(6): 39-44 http://monthlyreview.org/2013/11/01/its-the-system-stupid/

-

Despain, Hans G. 2013b Review of The Endless Crisis: How Monopoly-Finance Capital Produces Stagnation and Upheaval from the USA to China by John Bellamy Foster and Robert McChesney, January 30 https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviewofbooks/reviews/2013/694

-

Despain, Hans G. 2012 Pragmatic Employment Policy Post-Keynesian Economics Forum November 16 http://pke-forum.com/2012/11/16/pragmatic-employment-policy/

-

Foster, John Bellamy and McChesney, Robert W. 2012 The Endless Crisis: How Monopoly-Finance Capital Produces Stagnation and Upheaval from the USA to China New York: Monthly Review Press.

-

Galbraith, James K. 2012 Inequality and Instability: A Study of the World Economy Just Before the Great Crisis Oxford University Press, Oxford.

-

Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1973 Economics and the Public Purpose Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

-

Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1967 [2007] The Industrial State Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

-

Lapavitsas, Costas. 2013 Profiting without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All London and New York: Verso.

-

Minsky, Hyman P. 2013 Ending Poverty: Jobs, Not Welfare Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Levy Economics Institute.

URL: https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviews/7923_the-end-of-normal-review-by-hans-g-despain/

This review is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License

One comment