笨狼发牢骚

发发牢骚,解解闷,消消愁

正文

大家没耐心,先说结论。

明年全国平均医疗费用会长10-12%,公司政府都一般。如果你既不是有钱人又不是穷人,还要自己买保险的,认命吧,至少20%。

原因?

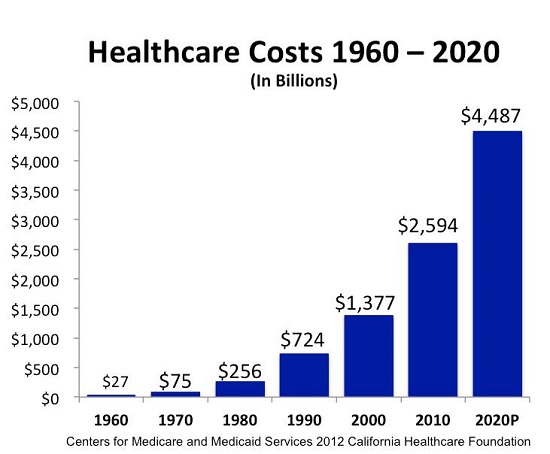

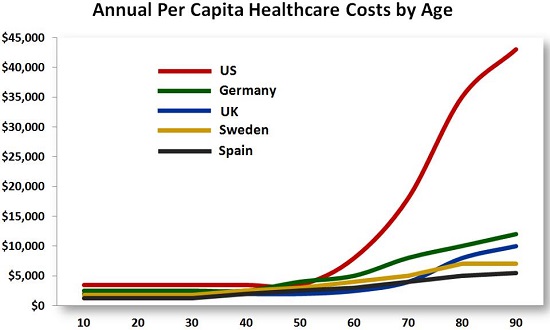

(1)医疗花销还是在大幅上涨,尤其是药(参见:去年美国医药新高,那种病最要命?),医院有不少措施降低费用,但不能取代其利用垄断、资源稀少的特殊地位赚钱的主要目的;

(2)奥巴马医保:有医保的人大大增多,好事儿。不过没人愿意付钱,两党还是那招:民主党发福利,共和党要减税。怎么办?从一部分手里抢。那部分人,你自己知道。

下面列举列举证据。

(一)两个指数

Milliman, Inc. released their annual Medical Index

According to Milliman, this year’s MMI is a 6.3% increase from last year’s

U.S. News Annual Health Care Index

报道标题是:U.S. News Health Care Index Shows Massive Increase in Consumer Costs美国新闻网站上模拟图表:鼠标指到之处显示具体分项指标

For the 2015 Index, overall results show a steady upward trend

At the same time that the government is becoming a more dominant force in health care, the index shows that consumers with private insurance have taken on a greater share of costs for their care.

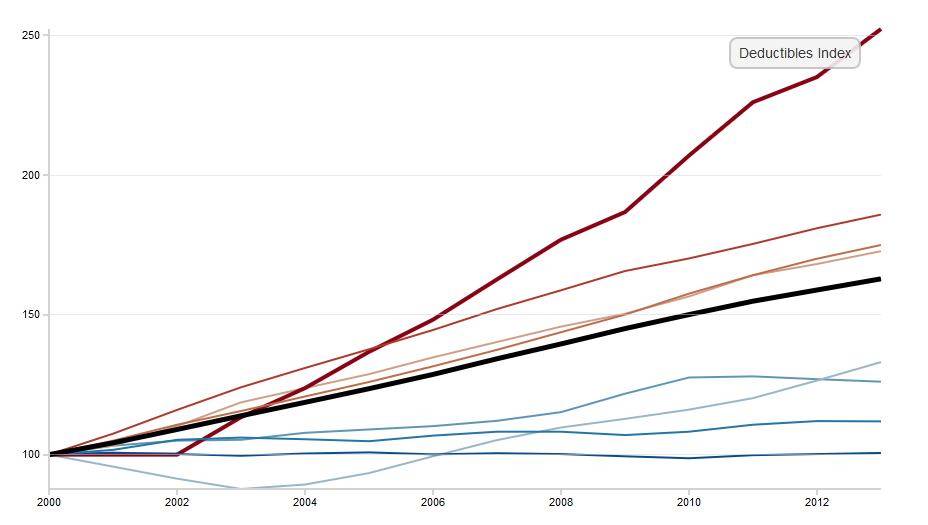

But deductibles are the components that have seen the most growth from 2002 to 2013

自掏费最甚。

(二)奥巴马医保的效应

《赫芬顿邮报》

Why Obamacare Premiums Will Probably Rise More Quickly Next Year

Premiums in the the Affordable Care Act’s new marketplaces rose more slowly in 2014 and 2015 than initial projections had suggested they would.《华尔街日报》(见下)两篇报道。

Don't bet on the same thing happening in 2016.

“the people who signed up for their policies in 2014 are running up higher medical bills”, "healthy people aren’t lining up for coverage":最糟的情形。然而,去年CareFirst在马里兰要涨23-30%,被州政府拒。只涨了10-16%。不同州见差别也很大。

网间对华尔街日报报道的的辩论:

反奥巴马医保的声音:Obamacare Insurance Premiums to Jump, up to 51%

不得了了支持的:Letting the air out of rate-increase hysteria

耸人听闻,简单算术错误,以扁盖全。《华尔街日报》

Health Insurers Seek Hefty Rate Boosts

In New Mexico, market leader Health Care Service Corp. is asking for an average jump of 51.6% in premiums for 2016. The biggest insurer in Tennessee, BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee, has requested an average 36.3% increase. In Maryland, market leader CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield wants to raise rates 30.4% across its products. Moda Health, the largest insurer on the Oregon health exchange, seeks an average boost of around 25%. Anthem Inc., in Virginia, wants an average increase of 13.2%. Blue Care Network, part of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, applied for a 10% average increase.《华尔街日报》

In Washington state and Vermont, the market leaders have sought relatively modest average increases, akin to those proposed last year, of 9.6% and 8.4%, respectively. In Indiana and Connecticut, the leading plans want 3.8% and 2% boosts.

BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee lost $141 million from exchange-sold plans

Health Costs Hinge on Supreme Court Ruling

不是有钱人又不是穷人,还要自己买保险的,首当其中,重灾户,政府企业有钱人穷人掠夺的对象。认命吧。

Michael Kole’s monthly health-insurance premium to cover himself and his family grew to $848 from $513, one of millions of Americans who earn too much to qualify for government subsidies

然而:a coming decision by the Supreme Court may invalidate subsidies to more than 7.5 million people who bought plans on the federal exchange

(三)

【附录:报道】

《华尔街日报》2015.05.21

Health Insurers Seek Hefty Rate Boosts

Proposals set the stage for debate over federal health law’s impact

By Louise Radnofsky

Major insurers in some states are proposing hefty rate boosts for plans sold under the federal health law, setting the stage for an intense debate this summer over the law’s impact.

In New Mexico, market leader Health Care Service Corp. is asking for an average jump of 51.6% in premiums for 2016. The biggest insurer in Tennessee, BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee, has requested an average 36.3% increase. In Maryland, market leader CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield wants to raise rates 30.4% across its products. Moda Health, the largest insurer on the Oregon health exchange, seeks an average boost of around 25%.

All of them cite high medical costs incurred by people newly enrolled under the Affordable Care Act.

Under that law, insurers file proposed rates to their local regulator and, in most cases, to the federal government. Some states have begun making the filings public, as they prepare to review the requests in coming weeks. The federal government is due to release its rate filings in early June.

Insurance regulators in many states can force carriers to scale back requests they can’t justify. The Obama administration can ask insurers seeking increases of 10% or more to explain themselves, but cannot force them to cut rates. Rates will become final by the fall.

“After state and consumer rate review, final rates often decrease significantly,” said Aaron Albright, a spokesman for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the federal agency overseeing the health law.

Consumer groups are demanding federal and state officials put premiums requests under the microscope this year.

“We are really wanting to see very vigorous scrutiny,” said Cheryl Fish-Parcham, director of the private insurance program at Families USA, a group that advocates for the health law. Her group wants regulators and the public to debate insurers’ assumptions about rates and look for ways they could save money.

Insurers say their proposed rates reflect the revenue they need to pay claims, now that they have had time to analyze their experience with the law’s requirement that they offer the same rates to everyone—regardless of medical history.

Health-cost growth has slowed to historic lows in recent years, a fact consumer groups are expected to bring up during rate-review debates. Insurers say they face significant pent-up demand for health care from the newly enrolled, including for expensive drugs.

“This year, health plans have a full year of claims data to understand the health needs of the [health insurance] exchange population, and these enrollees are generally older and often managing multiple chronic conditions,” said Clare Krusing, a spokeswoman for America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry group. “Premiums reflect the rising cost of providing care to individuals and families, and the explosion in prescription and specialty drug prices is a significant factor.”

David Axene, a fellow at the Society of Actuaries, said some insurers were trying to catch up with the impact of drugs such as Sovaldi, a pricey pill that is first in a new generation of hepatitis C therapies.

Mr. Axene, who helps many health plans set rates but didn’t work with the big plans in Maryland, New Mexico, Oregon or Tennessee, said insurers knew they would have to have “extreme evidence” to support their requests for the year ahead. “Somebody sincerely believed that they needed it,” he said.

In some of the dozen states where The Wall Street Journal reviewed filings that are public, the biggest insurers are seeking significant but less eye-popping increases. Anthem Inc., in Virginia, wants an average increase of 13.2%. Blue Care Network, part of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, applied for a 10% average increase.

In Washington state and Vermont, the market leaders have sought relatively modest average increases, akin to those proposed last year, of 9.6% and 8.4%, respectively. In Indiana and Connecticut, the leading plans want 3.8% and 2% boosts. So far, Maine is the only state where the market leader proposed keeping rates generally flat.

The 2010 health law made sweeping changes to the way medical insurance is sold to consumers who don’t get coverage through jobs or a government program such as Medicare. The federal government subsidizes premiums for some consumers, based on income, and the validity of those subsidies in most of the country is the subject of a lawsuit the Supreme Court is expected to decide in late June.

The filings from insurers are based on the assumption that those subsidies remain in place.

Insurance premiums have become a top issue for consumers and politicians as they evaluate how well the law is working. Obama administration officials weathered a storm as some younger, healthier consumers saw their premiums jump when the law rolled out, but were also able to point to modest premiums overall as insurers focused on other ways to keep costs down, such as narrow provider networks.

For 2015 insurance plans, when insurers had only a little information about the health of their new customers, big insurers tended to make increases of less than 10%, while smaller insurers tried offering lower rates to build market share.

BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee, CareFirst in Maryland and Moda in Oregon all said high medical claims from plans they sold over insurance exchanges spurred their rate-increase requests.

The Tennessee insurer said it lost $141 million from exchange-sold plans, stemming largely from a small number of sick enrollees. “Our filing is planned to allow us to operate on at least a break-even basis for these plans, meaning that the rate would cover only medical services and expenses—with no profit margin for 2016,” said spokeswoman Mary Danielson. The plan’s lowest monthly premium for a midrange, or “silver,” plan for a 40-year-old nonsmoker in Nashville would rise to $287 in 2016 from $220.

Tennessee Insurance Commissioner Julie Mix McPeak said she would be “surprised if we settled on 36.3%” as requested for the Blue plans’ average rate increase, but a significant boost might be allowed. She said data her team examined reflected big medical-claim costs.

CareFirst said its monthly claims per member nearly doubled to $391 in 2014 from $197 the year before. Its monthly premium for a 40-year-old nonsmoker in Annapolis with a silver plan would rise to $306 in 2016 from $244.

In Maryland, “premiums cannot be excessive but they cannot be too little,” said Insurance Commissioner Al Redmer. His predecessor rejected a similar 30% request from CareFirst last year, but allowed a 16% increase.

Moda Health said that with more than 100,000 individual members, it had the best data “on the care actually being received by these Oregonians. Our proposed rates reflect that.”

Under Moda’s proposal, a 40-year-old nonsmoker in Salem would pay $296 a month in 2016 for a silver plan, up from $245 a month this year. “It is a balance,” said Oregon Insurance Commissioner Laura Cali of her rate-review process.

Greg Thompson, a spokesman for Health Care Service Corp., the carrier seeking a 51.6% increase in New Mexico, said the proposed rates reflected high medical costs, and, like everyone else’s, were based on actuarial science. “There’s really no incentive for us to overprice,” he said.

New Mexico Insurance Commissioner John Franchini said insurers can revise their requests before June. He also has the power to reject rates.

“This is round one,” he said.

《华尔街日报》2015.05.25

Health Costs Hinge on Supreme Court Ruling

Subsidies that made insurance plans affordable face a crucial test with decision expected in June

Michael Kole, whose monthly premiums have gone to $848 from $513 since the Affordable Care Act kicked in, says he gave up renting an office and now works at home to save money

By Stephanie Armour

After the Affordable Care Act kicked in, Michael Kole’s monthly health-insurance premium to cover himself and his family grew to $848 from $513. Like others, he wasn’t happy about it. “It’s taking a lot out of pocket,” he said.

The 52-year-old sales and marketing entrepreneur is one of millions of Americans who earn too much to qualify for government subsidies on policies purchased through the federal insurance exchange. To save money, he said, he now works from home instead of renting an office.

Many people are paying more, and the reasons are simple: The health law requires that policies offer broad coverage and greater protection against catastrophic medical costs—and everybody is supposed to be covered. Others, thanks to government subsidies, are paying less.

But a coming decision by the Supreme Court may greatly complicate matters. The court is expected by the end of June to rule on a lawsuit seeking to invalidate subsidies to more than 7.5 million people who bought plans on the federal exchange.

If the court upholds the lawsuit, those people will land in the same boat as their more well-heeled compatriots. People with individual coverage in 2010 and 2012 who bought silver and bronze plans on the exchange after the law took effect saw total premiums and out-of-pocket payments rise an estimated 14% to 28%, according to a study last year by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

“Should subsidies be lost, the formerly subsidized will face premiums and out-of-pockets that are already a reality for the unsubsidized,” said Kev Coleman, head of research and data at HealthPocket Inc., a company that analyzes health-insurance costs across the U.S.

The lawsuit before the high court, King v. Burwell, asserts that language in the health law excludes subsidies to people who bought coverage on the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov. Upholding the suit would pressure the Republican-controlled Congress—including many who oppose the law—and GOP leaders are considering alternative plans, including a contingency option that would allow people to keep their subsidies until 2017.

No backup plan

The Obama administration has said it doesn’t have a backup plan if the subsidies are struck down. Leading Republicans see the court case as a chance to replace the law, and have been working on options that keep some components of the ACA but end, for example, some of the benefits now required on health plans.

Supporters of the lawsuit say a win by the plaintiffs would, in effect, free millions of Americans from paying a penalty if they forgo coverage: The law exempts individuals who can’t afford to pay for a health-care plan.

The average tax credits for plans bought over the federal exchange cover 72% of the premiums for those eligible, according to Obama administration officials, reducing the average monthly cost to about $100. That means if the court upholds the lawsuit, average monthly costs could more than triple to about $350. The decision would apply only to people living in up to 37 states that use the federal exchange; 13 states and the District of Columbia operate their own exchanges.

About 87% of those who bought a plan or were re-enrolled in the federal marketplace this year will get subsidies to lower their premium costs. Eliminating the subsidies would raise premiums on individual plans by 47% in those states, prompting enrollment in the individual market to fall by as much as 70%, according to a Rand Corp. study. All told, it would lead to about eight million people becoming uninsured because of higher costs, the study found.

“For many people getting coverage through the marketplaces, the combination of premiums and out-of-pocket expenses is going to be quite significant, maybe crushing for some people,” said Mark Rukavina, founder of Community Health Advisors LLC, a Chestnut Hill, Mass.-based health consultancy.

Health plans have become more expensive since passage of the law because, in addition to broader coverage, they must cap out-of-pocket expenses, unlike many older policies. Insurers also can no longer exclude such benefits as maternity, mental health`and prescription-drug coverage. They also can’t deny coverage or charge more for someone because of an existing condition, spreading higher costs to healthier customers.

“Plans before the Affordable Care Act lacked the financial and consumer protections now being enjoyed by millions of people, and that makes price comparisons misleading,” said Katie Hill, a spokeswoman for the Department of Health and Human Services.

Since the law was passed, the share of Americans without health insurance dropped to 11.9% for the first quarter of 2015 from a high of 18% in the fall of 2013, according to Gallup and the Healthways company, which began measuring coverage in 2008.

More people are getting more coverage—but at a price that has many who don’t get subsidies grumbling. Lance Taylor, 64, a retired commercial real-estate broker in Victorville, Calif., said he used to pay $431 a month to cover himself and his daughter with an annual deductible of $6,000. The plan was canceled because it didn’t meet the new requirements, he said, and its replacement policy costs $731 a month. He doesn’t qualify for a subsidy.

“Every time I write the check, I grit my teeth,” he said, angry about paying for maternity benefits and newborn-care coverage that he doesn’t need.

Higher out-of-pocket costs accompany the new plans, according to an analysis conducted this year for The Wall Street Journal by HealthPocket: The average family deductible for an economical bronze plan was $10,545; for the more expensive silver plan it was $6,010. In 2013, before the law took full effect, the average family deductible was $4,230.

Besides the insurance deductible, consumers also face higher out-of-pocket expenses for medical procedures and expenses. HealthPocket found the average coinsurance fee for inpatient hospitals services jumped to 27% of the cost on bronze plans; 2013 pre-reform plans averaged 20% for similar care.

“The same law has very different implications depending on a person’s circumstances,” said Mr. Coleman, HealthPocket’s head of research. “For some, it means new access to health care at an affordable cost, and to others it means dramatic increases in premiums and deductibles. Neither side is wrong.”

Public is divided

Public opinion is divided on the law, but the proportion of Americans in favor recently moved ahead for the first time since November 2012: 43% reported a favorable view of the law compared with 42% who held an unfavorable view, according to an April poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Wendy Morris, a 48-year-old estate and probate lawyer in Estero, Fla., paid $471 a month for a $1,500 deductible before the health law. She has since bought a platinum plan—the most expensive—on the exchange with a $573 monthly premium, no deductible and a $2,000 limit on out-of-pocket expenses.

Ms. Morris said the higher premium was worth the additional coverage, including the assurance that any medical bills exceeding $2,000 would be paid by her insurer, no matter how costly. “It’s peace of mind,” she said.

Some people are paying more because they have retired, were laid off or left jobs that provided insurance. Others paying more include people ages 26 and older who can’t remain on their parents’ plan and must have their own.

Mike Tilbury of New Orleans buys health insurance for his 26-year-old son, Patrick, a self-employed metal fabricator and welder who lives in Austin, Texas. His son’s previous policy cost $130 a month with a $1,300 deductible, Mr. Tilbury said, but it didn’t meet the law’s requirements.

Mr. Tilbury bought an individual plan for his son, who didn’t qualify for a subsidy, that met the law’s minimum requirements. It cost $212 a month, but what worries Mr. Tilbury most is the plan’s $6,000 annual deductible.

“This puts us in a real tough spot if anything happens to him, ” said Mr. Tilbury, who is 62 years old and retired from the pharmaceutical industry. “His deductible increased by six times, so how is the model working?…He’ll most likely never get much benefit from this unless he becomes seriously ill or injured.”

ENLARGE

Some people decide to skip coverage and pay a penalty. A March survey by McKinsey & Co. found that a third of consumers who were uninsured this year—and had shopped for health coverage on or off the exchanges—said they didn’t buy a plan because they couldn’t afford it. The penalty this year for failing to carry insurance is $325 for an adult, or 2% of yearly household income, whichever is higher.

Some consumers with modest incomes say that even with a subsidy, higher prices have made their health coverage costly. The loss of subsidies in many cases would make insurance even more unaffordable or beyond reach.

Kristine Stewart Hass of Detroit is a 49-year-old a freelance writer and editor and married mother of five. Before the law took effect, she paid nearly $300 for family health coverage with a $5,000 deductible. The plan was canceled because it didn’t meet the law’s requirements.

This year, she signed up for a bronze plan on the federal exchange. She now pays $581 a month after qualifying for a subsidy of about $300 a month. Her family’s annual deductible more than doubled to about $12,000: “We’d have to use credit cards to afford it,” she said. “It’s great that more people have coverage, but for us, it’s less affordable.”

A decision invalidating the subsidies would by next year eliminate $28.8 billion in tax credits and cost-sharing reductions for 9.3 million people, according to a study by the Urban Institute.

Average premiums for individual coverage in the affected states would increase by 35%, the study found, presuming that people with more medical needs would remain insured, shrinking the proportion of healthy policyholders.

Christopher Currie’s monthly premiums went to $470 from $287. “It’s had a huge impact,” said the 44-year-old chief executive of Aerialink Mobile Data Communications Solutions, a Chicago company that delivers text messages.

Mr. Currie said his own financial strain is just a small taste of increases that could hobble others if the Supreme Court strikes down subsidies on the federal exchange. “Everybody is going to be paying more than what they were paying years ago,” he said.

AACR Annual Meeting 2015

Web Cast

评论

目前还没有任何评论

登录后才可评论.