风萧萧_Frank

以文会友德国作为工业超级大国的时代即将结束

https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/germany-s-days-as-an-industrial-superpower-are-coming-to-an-end-1.2033273

Wilfried Eckl-Dorna、Jana Randow、Carolynn Look 和 Petra Sorge,彭博新闻

Feb 10, 2024

(彭博社)——去年秋天,在杜塞尔多夫一个巨大的生产车间里,号角演奏者阴沉的音调伴随着一家百年工厂的最后一幕。

如需德语版本,请点击此处。 订阅我们的德国每日时事通讯。

在闪烁的照明弹和火把中,1,600 名失业人员中的许多人面无表情地站着,看着工厂最后一个产品——钢管——在轧机上被磨平成完美的圆柱体。 该仪式结束了德国工业化鼎盛时期开始的长达 124 年的运行,并经历了两次世界大战,但未能在能源危机的余波中幸存下来。

在过去的一年里,这样的结局已经多次重复,凸显了德国面临的痛苦现实:它作为工业超级大国的日子可能即将结束。 自2017年以来,欧洲最大经济体的制造业产出一直呈下降趋势,并且随着竞争力的削弱,下降速度正在加快。

“老实说,希望不大,”GEA Group AG 的首席执行官 Stefan Klebert 说道。GEA Group AG 是一家制造机械供应商,其历史可以追溯到 1800 年代末期。 “我真的不确定我们能否阻止这种趋势。 许多事情必须很快改变。”

德国工业机器的基础已经像多米诺骨牌一样倒塌了。 美国正在远离欧洲,并寻求与跨大西洋盟友竞争气候投资。 中国正在成为一个更大的竞争对手,并且不再是德国商品的贪得无厌的买家。 对一些重型制造商来说,最后的打击是俄罗斯大量廉价天然气的终结。

除了全球动荡之外,柏林的政治瘫痪也加剧了长期存在的国内问题,例如破旧的基础设施、劳动力老龄化和繁琐的官僚作风。 教育系统曾经是一个优势,但现在却是公共服务投资长期缺乏的象征。 Ifo 研究所估计,到本世纪末,数学技能的下降将使经济损失约 14 万亿欧元(15 万亿美元)。

阅读更多:德国担心大众汽车正在走向无路可走

在某些情况下,工业减速是小步进行的,例如缩减扩张和投资计划。 其他的则更为明显,例如转移生产线和裁员。 在极端情况下——比如瓦卢瑞克 SACA 的管道厂,曾经是倒闭的工业巨头曼内斯曼的一部分——结果是永久关闭。

“震惊是巨大的,”从十几岁起就在该工厂工作的沃尔夫冈·弗雷塔格 (Wolfgang Freitag) 说。 59岁的他现在的工作是拆解设备出售,并帮助老同事找到新工作。

德国仍然拥有一批令人羡慕的小型敏捷制造商,德国央行和其他机构拒绝接受全面去工业化即将到来的观点。 但随着改革陷入停滞,尚不清楚什么会减缓衰退。

“我们不再具有竞争力,”财政部长克里斯蒂安·林德纳在本月早些时候的彭博社活动中表示。 “我们变得越来越穷,因为我们没有增长。 我们正在落后。”

11 月中旬,法院对借贷措施的裁决引发了预算危机,导致德国总理奥拉夫·肖尔茨 (Olaf Scholz) 的焦躁联盟陷入进一步混乱,导致政府几乎没有投资余地。

德国工商会外贸负责人沃尔克·特雷尔表示:“即使你不是悲观主义者,也会认为我们目前所做的还不够。” “结构变化的速度令人目眩。”

沮丧情绪很普遍。 尽管最近几周有数十万人走上街头抗议极右极端主义,但反移民的德国另类选择党(AfD)在民意调查中领先于所有三个执政党,仅落后于保守派集团。 根据《明镜周刊》对最近调查的分析,肖尔茨领导的社会民主党联盟得到了 34% 选民的支持。

阅读更多:极右势力在德国崛起,肖尔茨不知所措

米其林北欧地区负责人玛丽亚·罗特格 (Maria Röttger) 表示,工业竞争力的下降可能使德国陷入螺旋式下降。 这家法国轮胎制造商将关闭其两家德国工厂,并在 2025 年底之前缩小第三家工厂的规模,此举将影响 1,500 多名工人。 美国竞争对手固特异也有类似的两个工厂计划。

她在接受采访时表示:“尽管我们的员工积极主动,但我们已经无法以有竞争力的价格从德国出口卡车轮胎了。” “如果德国不能在国际环境中具有竞争力的出口,该国就会失去其最大的优势之一。”

其他考试

下降的情况经常出现。 GEA 正在关闭美因茨附近的一家泵厂,转而在波兰建立一个新工厂。 汽车零部件制造商大陆集团于 7 月宣布计划放弃一家生产安全和制动系统零部件的工厂。 其竞争对手罗伯特博世有限公司正在裁员数千名。

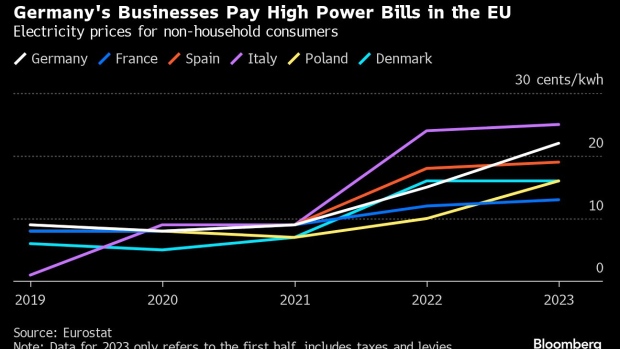

2022 年夏季的能源危机是一个主要催化剂。 尽管避免了冻结房屋和配给等最坏的情况,但价格仍然高于其他经济体,这增加了工资上涨和监管复杂性带来的成本。

受打击最严重的行业之一是化学品——这是德国失去廉价俄罗斯天然气的直接结果。 VCI 行业协会最近的一项调查显示,由于向清洁氢的过渡仍不确定,近十分之一的公司计划永久停止生产过程。 欧洲最大的化学品生产商巴斯夫公司(BASF SE)将裁员2,600人,朗盛公司(Lanxess AG)将裁员7%。

即使企业准备好投资,德国缓慢的官僚机构也没有跟上步伐。 GEA 在德国西部小镇厄尔德的一家工厂安装了太阳能发电设备,生产可将奶油与牛奶分离的设备。 去年一月,即开工前两个月,该公司申请了供电许可证,目前仍在等待批准——距离该项目启动已近两年。

疫情造成的干扰导致装配线陷入停滞,德国汽车制造商等待芯片和其他零部件长达数月之久,能源紧张很快就出现了,这突显了依赖分布广泛的供应商网络的风险,尤其是在亚洲。 阅读更多 : 欧洲经济引擎正在崩溃

中国现在在很多方面给德国制造麻烦。 除了向先进制造业的战略转移之外,这个亚洲超级大国经济放缓进一步削弱了对德国商品的需求。 与此同时,来自中国的廉价竞争令德国气候转型的关键行业感到担忧——而不仅仅是电动汽车。

太阳能电池板制造商正在关闭业务并裁员,因为他们难以与国家支持的中国竞争对手竞争。 总部位于德累斯顿的 Solarwatt GmbH 首席执行官德特勒夫·诺伊豪斯 (Detlef Neuhaus) 表示,该公司已经裁员 10%,如果今年情况没有改善,可能会将生产转移到国外。

德国面临的逆风需要适应。 对于风扇和通风机生产商 EBM-Papst 来说,工业危机意味着收购一家陷入困境的供应商。 为了保持灵活性,该公司将生产从汽车行业转向热泵和数据中心零部件。 它还希望将一些管理任务转移到东欧或印度。

“这不仅仅是能源,”首席执行官 Klaus Geißdörfer 在接受采访时表示。 “这也是德国员工数量的问题,目前德国的员工情况非常紧张。” 他补充说,十年之内,劳动年龄人口将太少,无法保持经济像今天一样运转。

德国央行在 9 月份的一份报告中得出结论,制造业的下滑(占经济的比重略低于 20%,几乎是美国水平的两倍)如果是渐进的,则不必担心。

对于像杜塞尔多夫的管道厂这样的基础制造商来说,这种趋势可能意味着道路的终结。 Freitag 是工厂工会的成员,目前正在帮助准备出售这片 90 公顷的土地。 他说,大部分设备最终都会被扔进废品场,这“让我的心和眼睛流泪”。

——在卡米尔·科瓦尔切的帮助下。

Germany's Days as an Industrial Superpower Are Coming to an End

Wilfried Eckl-Dorna, Jana Randow, Carolynn Look and Petra Sorge, Bloomberg News

Feb 10, 2024

, Source: Eurostat

(Bloomberg) -- In a cavernous production hall in Düsseldorf last fall, the somber tones of a horn player accompanied the final act of a century-old factory.

For a German version, click here. Subscribe to our German daily newsletter.

Amid the flickering of flares and torches, many of the 1,600 people losing their jobs stood stone-faced as the glowing metal of the plant’s last product — a steel pipe — was smoothed to a perfect cylinder on a rolling mill. The ceremony ended a 124-year run that began in the heyday of German industrialization and weathered two world wars, but couldn’t survive the aftermath of the energy crisis.

There have been numerous iterations of such finales over the past year, underscoring the painful reality facing Germany: its days as an industrial superpower may be coming to an end. Manufacturing output in Europe’s biggest economy has been trending downward since 2017, and the decline is accelerating as competitiveness erodes.

“There’s not a lot of hope, if I’m honest,” said Stefan Klebert, chief executive officer of GEA Group AG — a supplier of manufacturing machinery that traces its roots to the late 1800s. “I am really uncertain that we can halt this trend. Many things would have to change very quickly.”

The underpinnings of Germany’s industrial machine have fallen like dominoes. The US is drifting away from Europe and is seeking to compete with its transatlantic allies for climate investment. China is becoming a bigger rival and is no longer an insatiable buyer of German goods. The final blow for some heavy manufacturers was the end of huge volumes of cheap Russian natural gas.

Alongside global volatility, political paralysis in Berlin is intensifying long-standing domestic issues such as creaking infrastructure, an aging workforce and the snarl of red tape. The education system, once a strength, is emblematic of a long-term lack of investment in public services. The Ifo research institute estimates that declining math skills will cost the economy about €14 trillion ($15 trillion) in output by the end of the century.

Read More: Germany Frets Volkswagen Is Heading Down the Road to Nowhere

In some cases, the industrial downshift is taking place in small steps like scaling back expansion and investment plans. Others are more evident like shifting production lines and trimming staff. In extreme instances — like Vallourec SACA’s pipe plant, once part of fallen industrial giant Mannesmann — the consequence is permanent closure.

“The shock was huge,” said Wolfgang Freitag, who worked at the plant since he was a teenager. The 59-year-old’s job now is to disassemble equipment for sale and help his old colleagues find new work.

Germany still has an enviable roster of small, agile manufacturers, and the Bundesbank and others reject the notion that full-blown deindustrialization is anywhere close. But with reforms stalled, it’s unclear what will slow the decline.

“We are no longer competitive,” Finance Minister Christian Lindner said at a Bloomberg event earlier this month. “We are getting poorer because we have no growth. We are falling behind.”

Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s fractious coalition was thrown into further disarray in mid-November by a budget crisis sparked by a court ruling over borrowing measures, leaving the government with little leeway to invest.

“You don’t have to be a pessimist to say that what we’re doing at the moment won’t be enough,” said Volker Treier, foreign trade chief at Germany’s Chambers of Commerce and Industry. “The speed of structural change is dizzying.”

Frustration is widespread. Although hundreds of thousands of people have hit the streets in recent weeks to protest against far-right extremism, the anti-immigration Alternative für Deutschland, or AfD, is ahead of all three ruling parties in the polls — trailing only the conservative bloc. Scholz’s Social Democrat-led alliance has support from 34% of voters, according to a Spiegel analysis of recent surveys.

Read More: The Far Right Is on the Rise in Germany and Scholz Is at a Loss

Fading industrial competitiveness threatens to plunge Germany into a downward spiral, according to Maria Röttger, head of northern Europe for Michelin. The French tiremaker is shutting two of its German plants and downsizing a third by the end of 2025 in a move that will affect more than 1,500 workers. US rival Goodyear has similar plans for two facilities.

“Despite the motivation of our employees, we have arrived at a point where we can’t export truck tires from Germany at competitive prices,” she said in an interview. “If Germany can’t export competitively in the international context, the country loses one of its biggest strengths.”

Other examples of decline surface regularly. GEA is closing a pump factory near Mainz in favor of a newer site in Poland. Auto-parts maker Continental AG announced plans in July to abandon a plant that makes components for safety and brake systems. Rival Robert Bosch GmbH is in the process of slashing thousands of workers.

The energy crisis in the summer of 2022 was a major catalyst. While worst-case scenarios like freezing homes and rationing were avoided, prices remain higher than in other economies, which adds to costs from higher wages and regulatory complexity.

One of the hardest-hit sectors has been chemicals — a direct result of Germany’s loss of cheap Russian gas. With the transition to clean hydrogen still uncertain, nearly one in 10 companies are planning to permanently halt production processes, according to a recent survey by the VCI industry association. BASF SE, Europe’s biggest chemical producer, is cutting 2,600 jobs and Lanxess AG is reducing staff by 7%.

Germany’s sluggish bureaucracy also isn’t keeping pace, even when companies are prepared to invest. GEA installed solar capacity at a factory in the western German town of Oelde, where it makes equipment that can separate cream from milk. It applied for permits to feed in the power last January, two months before starting construction and is still waiting for approval — nearly two years after initiating the project.

The energy squeeze came quickly on the heels of disruptions from the pandemic that led to stalled assembly lines as German automakers waited months for chips and other components, underscoring the risks of relying on a far-flung network of suppliers, especially in Asia.Read More: Europe’s Economic Engine Is Breaking Down

China is now causing trouble for Germany in a number of ways. On top of its strategic shift into advanced manufacturing, a slowdown of the Asian superpower’s economy is sapping demand for German goods even further. At the same time, cheap competition from China is worrying industries key for Germany’s climate transition — and not just electric cars.

Manufacturers of solar panels are shuttering operations and cutting staff as they struggle to compete with state-supported Chinese rivals. Dresden-based Solarwatt GmbH has already cut 10% of its workforce and may relocate production abroad if the situation doesn’t improve this year, according to CEO Detlef Neuhaus.

Germany’s headwinds require adaptation. For EBM-Papst, a producer of fans and ventilators, the industrial crisis meant acquiring a struggling supplier. And to stay nimble, the company shifted production to components for heat pumps and data centers and away from the auto sector. It’s also looking to move some administrative tasks to eastern Europe or India.

“It’s not just energy,” CEO Klaus Geißdörfer said in an interview. “It’s also staff availability in Germany, which is now very tense.” Within a decade, the working-age population will be too small to keep the economy functioning as it does today, he added.

The Bundesbank concluded in a September report that a decline in manufacturing — which accounts for just under 20% of the economy, nearly twice the US’s level — isn’t worrying if it’s gradual.

Such a trend could mean the end of the road for more basic manufacturers like the pipe plant in Düsseldorf. Freitag, a member of the factory’s works council, is now helping prepare the 90-hectare site for sale. Much of the equipment will end up in a scrapyard, which “makes my heart and eyes weep,” he said.

--With assistance from Kamil Kowalcze.