风萧萧_Frank

以文会友中国在不断变化的经济秩序中的下一步行动

https://www.rbcwealthmanagement.com/en-asia/insights/chinas-next-act-in-a-changing-economic-order

随着各国逐渐摆脱冷战后激烈的全球化时代,世界制造业强国将如何适应新的经济范式?

作者:段茉莉,2023 年 8 月 14 日

加拿大皇家银行财富管理公司的“天壤之别:逆全球化迫在眉睫的风险与机遇”系列探讨了远离全球化的趋势及其对投资者、经济体和金融市场的影响。 该系列的最新专题聚焦于中国在全球供应链和制造业中的独特作用。

由于供应链高度复杂且相互关联,西方与中国脱钩是不现实的。 中国通过向供应链上游转移,正在赢得全球制造业的市场份额。

中国过去已经展现出克服技术限制影响的能力。 中国庞大的制造规模和完善的供应链应该为未来的技术创新奠定基础。

十多年前,中国开始从低端、劳动密集型零部件制造转向高科技、全系列产品制造。

中国国内市场太大,跨国公司不容忽视。 但我们认为跨国公司需要确定如何在中国寻求机遇,同时有效管理风险。

我们所目睹的供应链转型是国际贸易和商业的自然演变。 我们相信,中国能够像现代历史上许多其他国家一样成功度过这一时期。

新闻头条经常强调地缘政治和新冠肺炎 (COVID-19) 疫情在推动西方跨国公司将供应链迁出中国方面所发挥的作用。 这反过来又助长了一种叙事,强调这些因素是全球供应链和中国制造业变革的主要催化剂。

随着贸易流动从激烈的全球化时期转向更加分散的时期,地缘政治因素确实发挥了作用。 各国政府正在促进和激励制造业的在岸和友岸外包,许多跨国公司正在寻求供应链多元化。

然而,对于中国来说,我们认为情况比主流头条新闻描述的更为复杂,也没有那么悲观。

首先,我们认为,全球供应链的高度复杂性,加上中国工业部门的庞大规模和制造能力,使得许多跨国公司短期内与中国彻底决裂是不可取的、也不现实的。

其次,多年来,中国制造业和全球供应链的演变是为了应对与当前中美贸易和政治摩擦无关的力量。

即使发达国家的本土化和友好型外包趋势加快,我们认为中国在四十多年来与众多跨国公司建立的互利关系将使中国融入全球经济和投资格局。

供应链的相互关联性和复杂性远远超出想象

生产复杂产品的公司通常拥有四层或多层数千家供应商。

根据咨询公司麦肯锡公司的数据,科技公司拥有 125 家一级供应商(即最终产品的直接供应商或用于创建最终产品的完整组件),平均而言,所有级别的供应商超过 7,000 家。

一家汽车制造商通常拥有约 250 家一级供应商,但整个供应链的数量已增加至 18,000 家。

全球供应链的复杂性常常导致拥有上游产品或材料的国家的公司之间相互依赖。

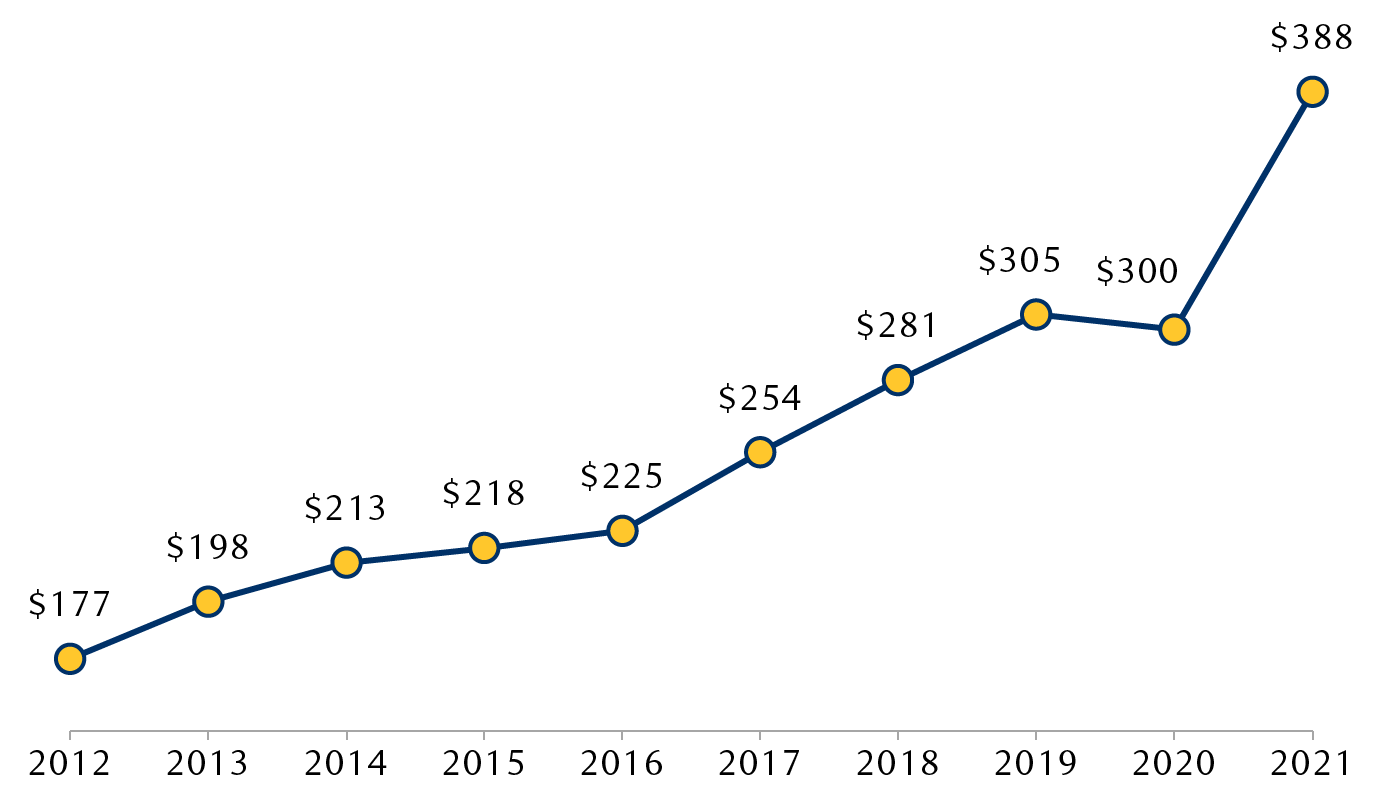

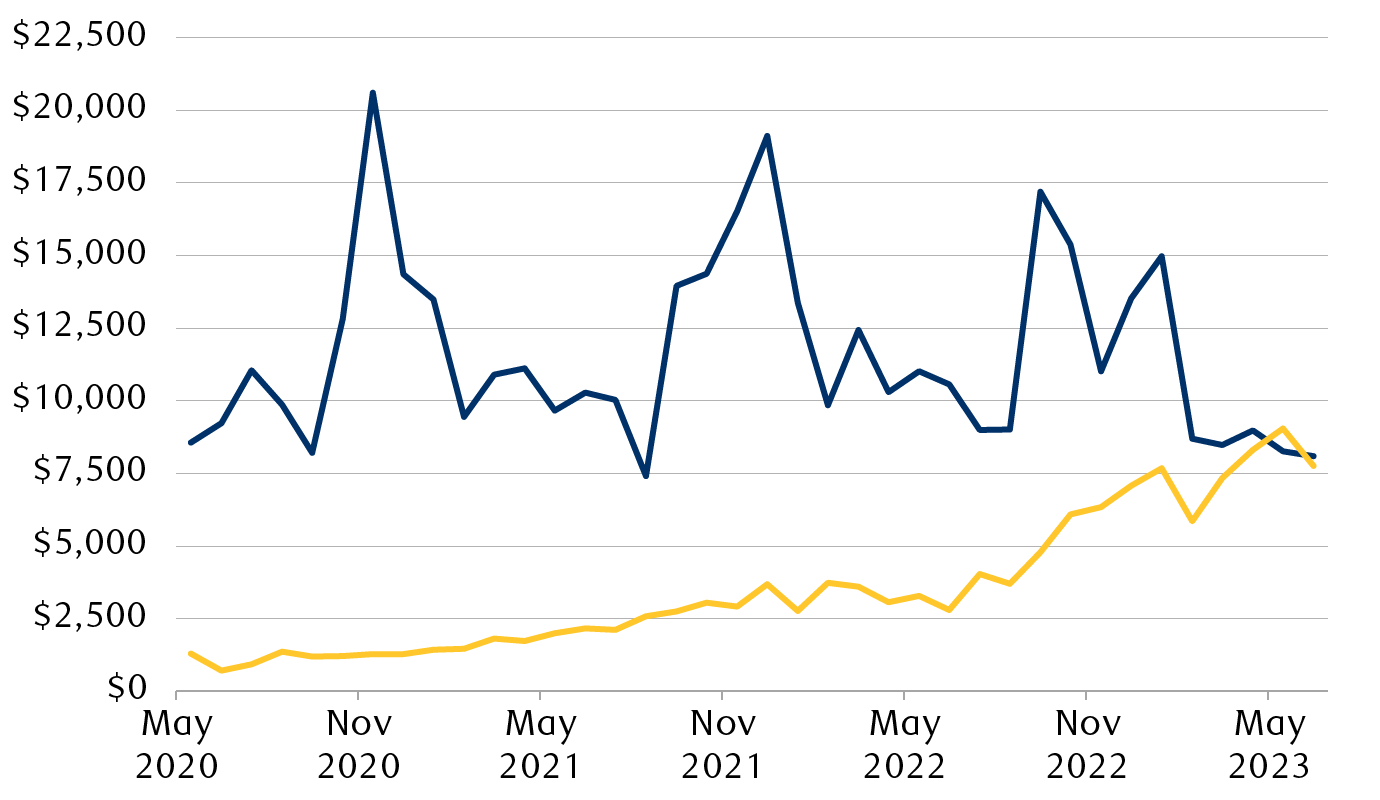

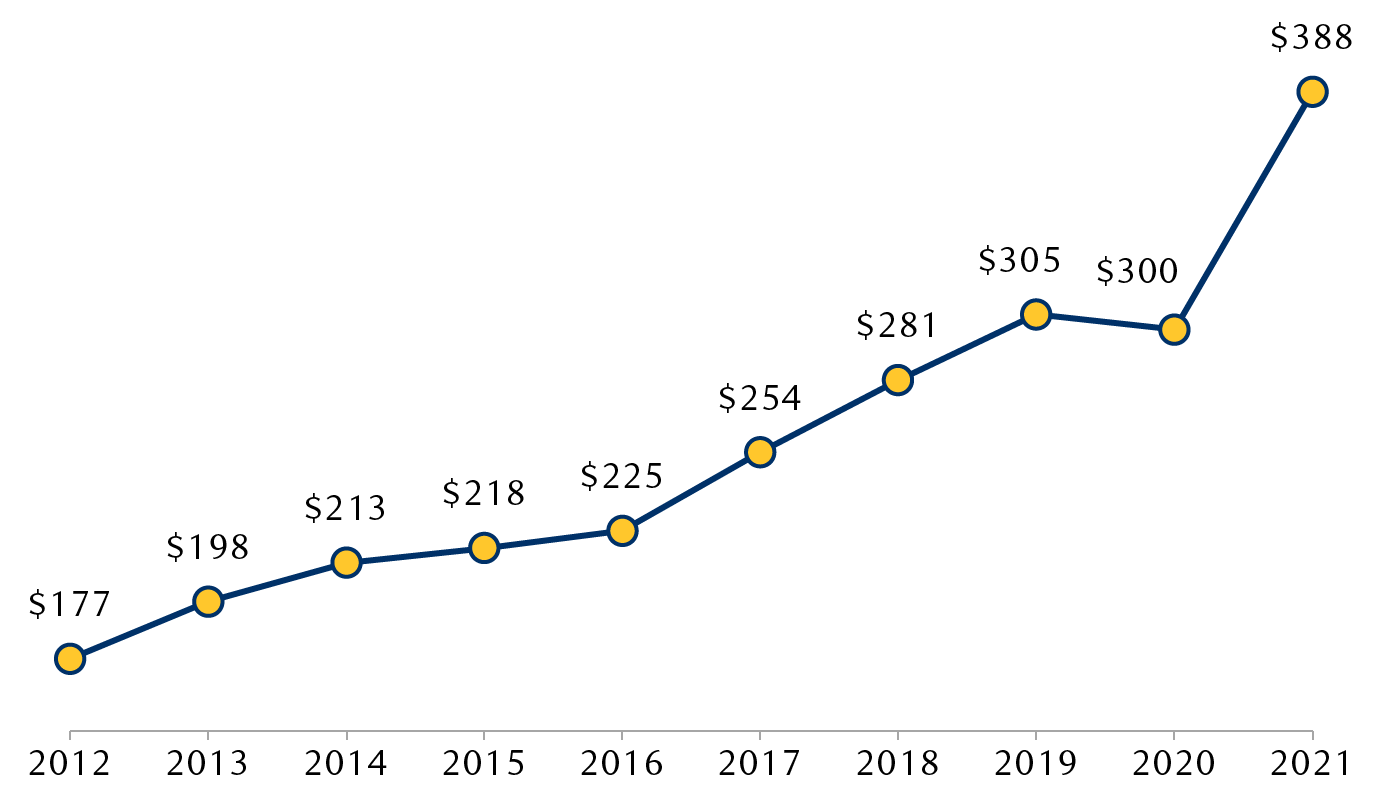

例如,随着东南亚10个东盟*国家的制造能力不断增强,它们与中国制造供应链的联系也更加紧密。 2012年,东盟成员国从中国进口了1770亿美元的商品。在短短10年内,这一数字到2021年增加了一倍多,达到3880亿美元。

过去十年中国对东盟的进口增长了一倍多美元(十亿)

2012年至2021年东盟国家从中国的进口额

折线图显示了2012年至2021年期间东盟国家从中国的进口额。该图显示,多年来进口额稳步增长,从2012年的1770亿美元增至2021年的3880亿美元,翻了一倍多。

*东南亚国家联盟 (ASEAN) 是一个区域性政府间组织,由 10 个成员国组成:印度尼西亚、马来西亚、菲律宾、新加坡、泰国、文莱、柬埔寨、老挝、缅甸和越南。

资料来源 – Statista、加拿大皇家银行财富管理; 截至 2021 年的年度数据

东盟地区仍然高度依赖中国的投入和资本货物,这对这些国家制造的产品至关重要。 如果跨国公司希望未来几年在该地区生产更多商品,我们认为中国生产也将在供应链中发挥有意义的作用。

中国庞大的制造业足迹

“中国制造”的标签对于很多人来说并不陌生,但中国制造的整体规模和范围可能仍然被低估。

中国制造业规模连续十多年位居世界第一。 据联合国称,2021年,中国制造业产值占全球的30%。 相比之下,欧盟总共占16%,美国占15%,日本和德国分别占6%和5%。

目前,中国是世界上唯一符合联合国统计参考分类系统所有制造业相关部分标准的国家。 这说明了中国生产能力的广泛性。 许多行业的称号位居世界第一。

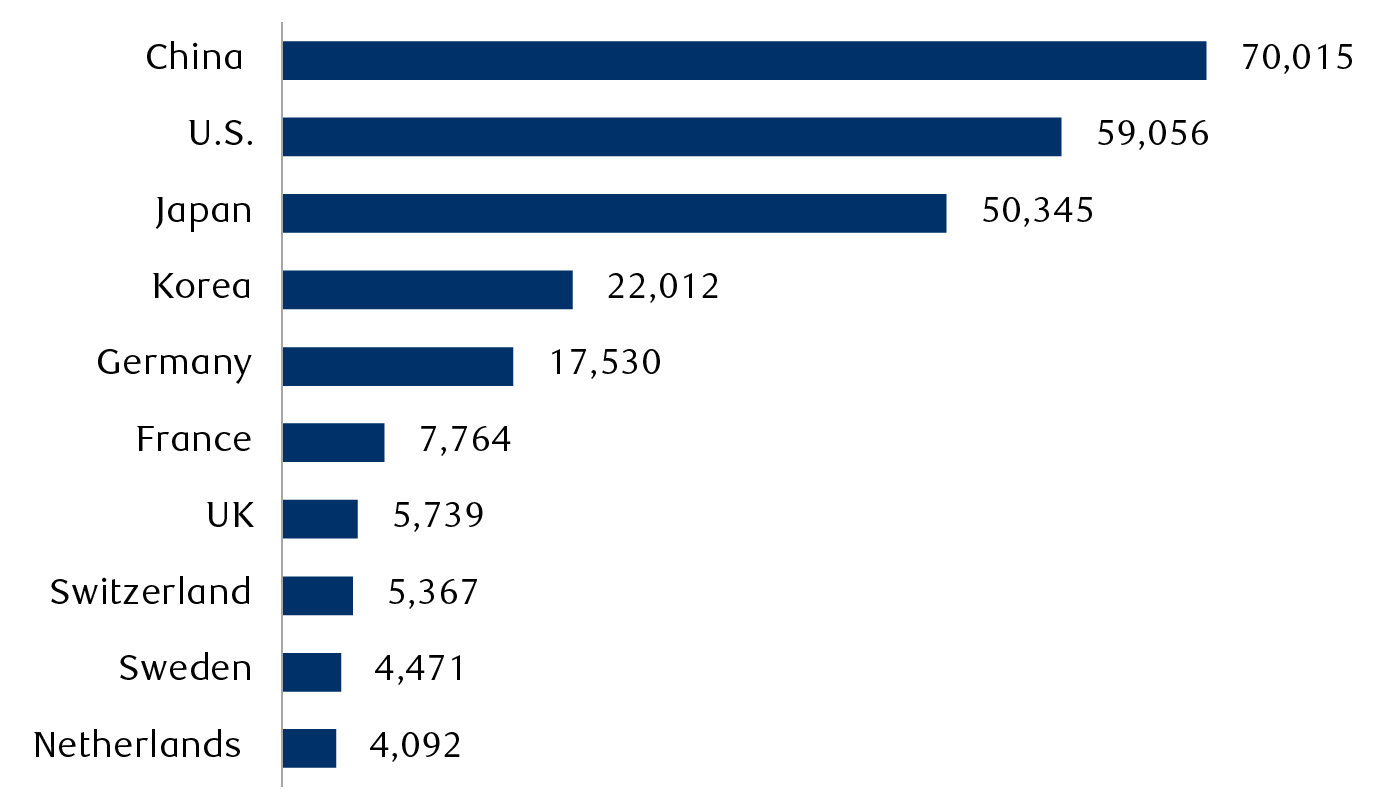

中国作为知识产权领导者的崛起也有助于其制造基地的成熟和发展。

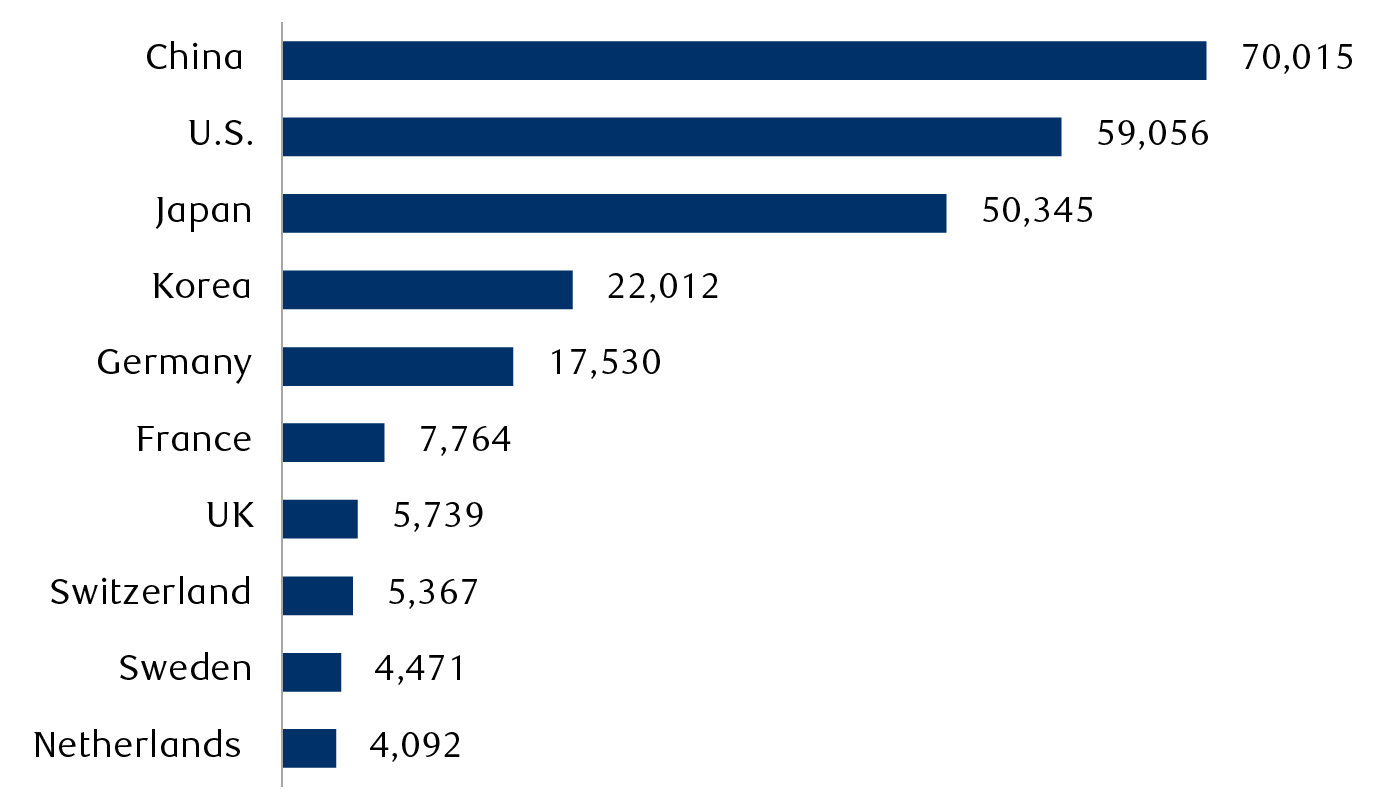

2019年,中国超越美国,成为根据世界知识产权组织(WIPO)《专利合作条约》申请国际专利的最大来源国。

2022年中国提交专利合作条约申请最多

根据《专利合作条约》提交专利申请最多的国家

条形图显示根据世界知识产权组织《专利合作条约》(PCT) 提交专利申请最多的前 10 个国家。 中国申请人提交了 70,015 件 PCT 申请,其次是美国(59, 056)、日本(50,345)、韩国(22,012)、德国(17,530)、法国(7,764)、英国(5,739)、瑞士(5,367) 、瑞典(4,471)和荷兰(4,092)。

资料来源 – 世界知识产权组织统计数据库(2023 年 2 月),加拿大皇家银行财富管理

随着中国从低成本制造中心转变为越来越注重创新和复杂制造技术的制造中心,我们认为该国将保持其制造主导地位,同时进军电动汽车等新兴战略领域。 )、电信、生物工程、人工智能(AI)等领域。

制造能力在技术上变得更加先进

过去几十年来,中国在各个行业建立了全面的供应链,这在很大程度上得益于跨国公司和战略合资企业的本土化进程。 这些合作使中国获得了技术和诀窍,并为自身的技术创新奠定了基础。

近年来,西方开始对中国获取人工智能、量子计算和先进半导体等关键技术实施限制,引发了人们对中国能否进一步向供应链上游迈进并实现其所谓的“技术自力更生”的能力的担忧。 ” 目标。

这可能会给中国的技术发展带来挑战,并可能减慢其发展速度。 然而,重要的是要记住,中国过去已经表现出克服技术限制影响的能力。 天宫空间站和中国电动汽车的开发就是两个例子。

天宫:从旁观者到独立航天强国

国际空间站(ISS)是美国、欧洲、俄罗斯、加拿大和日本之间的合作项目。 截至 2023 年 6 月,它已接待了来自 21 个不同国家的宇航员。

2011年,美国国会通过了一项由总统签署的法律,禁止美国国家航空航天局(NASA)向中国提供资助或与中国进行直接的双边合作,从而有效阻止了中国加入国际空间站。

作为回应,中国在接下来的十年里开发和发射单独的模块,以在 2023 年完成自己的永久空间站,称为“天宫”。

天宫建立了中国在太空的独立存在。 它使中国能够开展先进的科学研究,代表着中国作为全球太空强国迈出了改变游戏规则的重要一步。 随着国际空间站计划于 2031 年退役,天宫将成为唯一正在运行的空间站。

汽车工业:从新兴产业到高科技产业

过去几十年发展起来的全面供应链为中国汽车行业的技术进步铺平了道路。

一般的经验法则是,特定制造领域的生产规模越大,就越容易提高生产效率、产品质量和技术。

中国通过制定国家政策和资金支持、培养国内人才以及与其他国家建立战略互利联盟来寻求克服技术障碍。

中国汽车工业的发展,特别是电动汽车技术的快速进步,让我们可以深入了解该国扩大生产规模进入高科技制造业的能力。

20世纪70年代末和80年代政府改革开放后,中国汽车行业经历了快速增长。 该行业与大众、通用和本田等外国汽车制造商成立了合资企业。

起初,中国汽车工业严重依赖国外技术,特别是在内燃机汽车的核心部件发动机和变速箱设计方面。

随着时间的推移,中国发展了广泛的汽车供应链和制造能力,同时积极鼓励技术工程人才的发展。

2000年代初,中国开始探索新能源汽车。 2010 年代,政府出台了一系列旨在支持研发 (R&D) 和鼓励电动汽车采用的政策。

传统汽车生产中使用的许多技术和生产工艺可以转移到电动汽车制造中。 同时,电动汽车的核心部件和技术包括电池、电动机和电控系统,与传统内燃机汽车的组成部件和技术有很大不同。

凭借强大的制造技术和支持性的公共激励措施,中国汽车工业能够摆脱传统化石燃料动力传动系统的技术限制,并进军更先进、更清洁的技术。

Patent Result 最近的一份报告强调了中国在电动汽车充电专利方面的领先地位。 2010年至2022年,中国企业在该领域提交了41,011件专利申请,比日本高出52%,是美国电动汽车充电专利数量的近三倍。 中国现已超过日本、美国和欧洲,成为最大的新型电动汽车出口国。

中国从劳动密集型制造业转型

与当前中美地缘政治摩擦无关的其他因素也有助于改变中国的供应链和制造流程。 这些大多源于中国自身的经济发展。

过去20年来,随着中国经济的显着增长,劳动力成本增加了一倍多,迫使鞋类和服装制造等劳动密集型产业转移到劳动力更便宜的国家——很多情况下是转移到东盟国家。

这个过程可以追溯到十多年前中国开始制造业升级的时候。

一些劳动密集型产业开始从沿海制造业中心转移到欠发达的内陆城市和省份。

后来,随着那里劳动力成本的上升,生产开始向国外转移,中资工厂在东盟国家涌现。 中国制造业在该地区的投资范围包括纺织、消费电子产品、电动汽车供应链、制药等。

截至2021年,中国以140亿美元成为东盟地区第三大国际直接投资来源国,仅次于美国的400亿美元和东盟国家相互投资的210亿美元。

供应链多元化:低于宣传的水平

尽管供应链在一定程度上远离中国,但这种变化并不像人们想象的那么重要。 电子和机械行业就是一个很好的例子,它是全球贸易中最大的商品类别。

该行业的出口以中国为主,但近年来已向东盟国家转移。 与保尔森基金会有联系的美国智库Macro Polo的一项研究显示,2018年至2021年,中国对美国的电子产品出口额下降了10个百分点。大部分缺口被东盟国家填补。 美国前财政部长汉克·保尔森)。

人们很容易得出这样的结论:中国在全球制造业中的地位正在输给东盟国家。 然而,数据却讲述了不同的故事。 东盟国家在全球制造业中的收益相对较小; 该地区的市场份额从 2010 年的 3% 左右小幅上升到 2021 年的 5% 左右,而同期中国的份额从 20% 上升到 30%。

数据告诉我们,虽然部分制成品的最终组装可能已从中国转移到东盟,但中国的整体制造能力仍然较高。

中国正在逐步用更先进、更高附加值的制造业取代劳动密集型产业。 这种结构转型的典型例子是新能源汽车、太阳能电池和锂电池这三种可再生能源产品的出口繁荣。

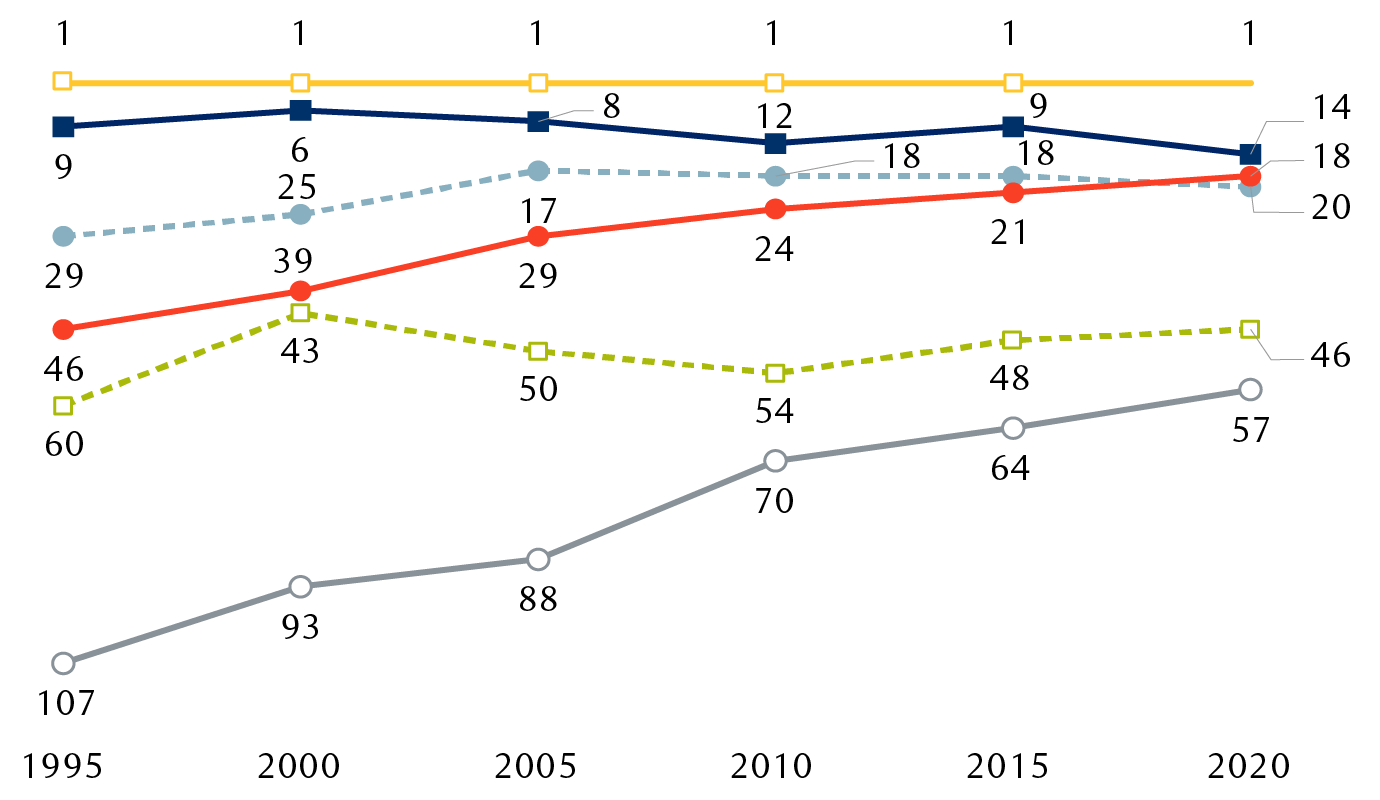

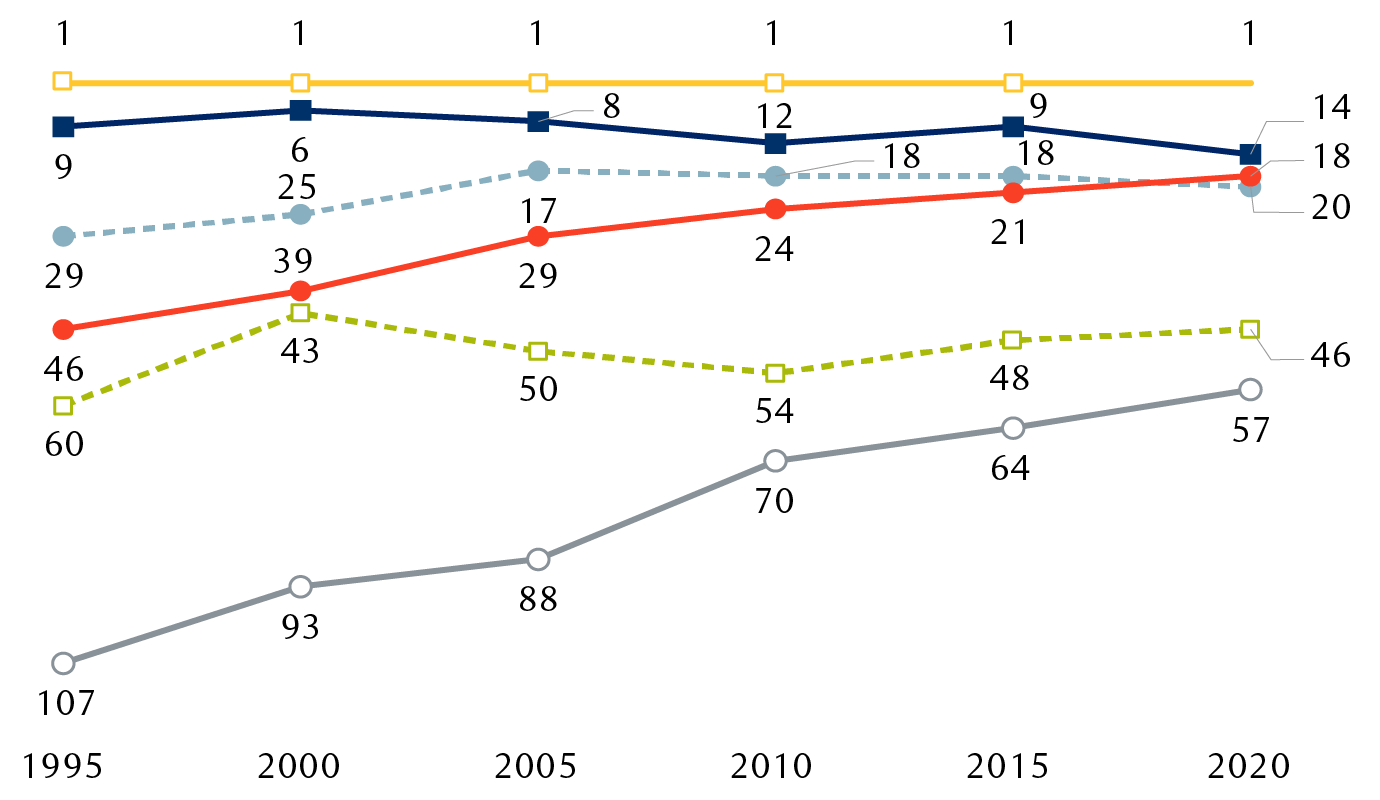

随着中国向供应链上游移动,其经济变得更加复杂

哈佛经济复杂性指数排名; “1”是最复杂的

哈佛经济复杂性指数排名

折线图显示了1995年至2020年各国(日本、美国、中国、墨西哥、印度和越南)复杂性排名。日本自1995年以来一直排名第一。中国的排名从1995年的第46位提升至2020年的第18位 美国排名多年来略有下降,2020年排名第14位,墨西哥1995年排名第29位,2020年上升至第20位。印度和越南排名分别从第60位上升至第46位,从第107位上升至第57位。

日本

我们。

中国

墨西哥

印度

越南

注:经济发展需要生产性知识的积累及其在更广泛、更复杂的行业中的运用。 哈佛增长实验室的经济复杂性指数(ECI)评估一个国家的生产知识状况。 随着一国出口数量和复杂程度的增加,该国的ECI趋向于“1”; 例如,在该数据中,日本的 ECI 一直最高,为 1,而越南目前最低,为 57,尽管其得分一直在提高。

资料来源 – 哈佛增长实验室、加拿大皇家银行财富管理

与此同时,中国已经改变了贸易模式,摆脱了依赖供应材料或零部件的加工贸易。 历史上,制造商一直采用加工贸易来寻求专业投入或降低劳动力成本。 其占中国出口总额的比重已从2000年的55%下降至20%左右。与此同时,制成品出口单位价值持续上升,表明产业升级正在进行。

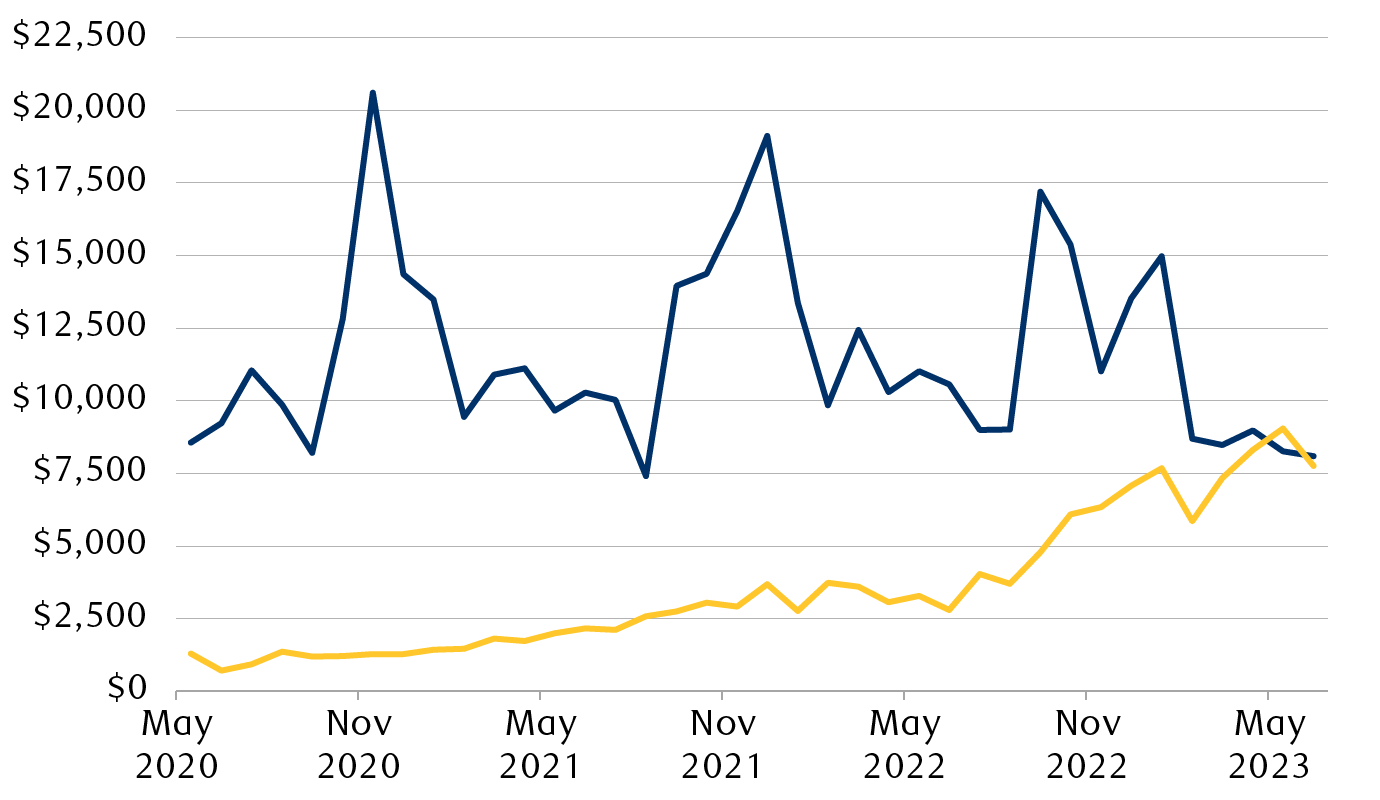

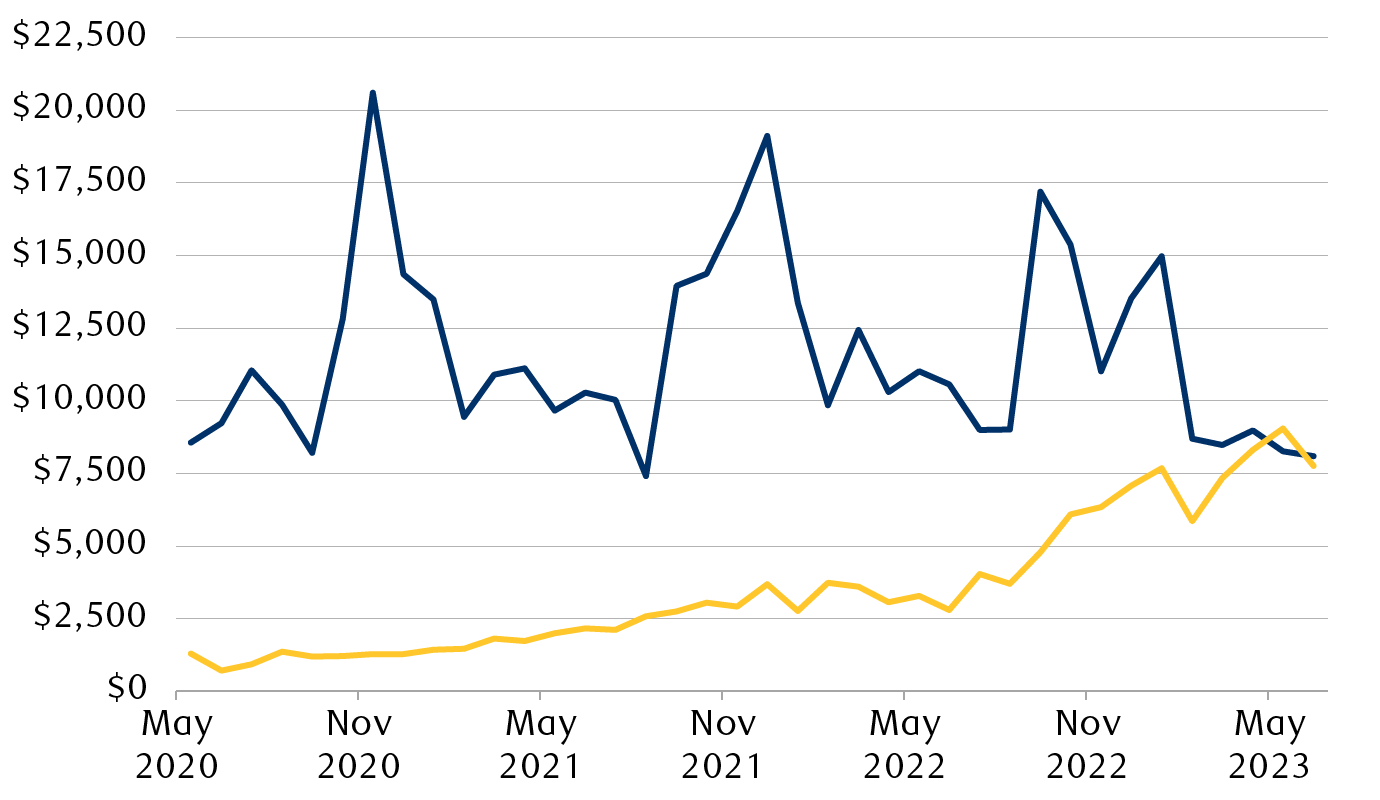

随着中国制造业变得更加复杂,汽车出口额激增

美元(百万)

2020年5月至2023年5月中国手机和汽车月度出口额

折线图显示了2020年5月至2023年5月中国手机和汽车的月度出口额。2020年5月汽车出口总额为13.05亿美元,并且一直在增长(最新读数为77.58亿美元)。 汽车出口额现已赶上手机(最新数据为81.01亿美元),手机是传统上重要的出口领域。

手机 汽车

资料来源 – 加拿大皇家银行财富管理公司、彭博社; 截至 2023 年 6 月的月度数据

中国仍将是一个有吸引力的投资目的地吗?

20世纪70年代和80年代改革开放后,中国与跨国公司建立了互利共赢的关系。 中国从跨国公司那里获得了技术和管理知识,而这些公司在中国享有较低的生产成本和较高的利润(我们认为这提振了股价),以及进入中国庞大的国内市场的机会。

然而,最近,跨国公司开始重新评估在中国的商业环境及其投资计划。

中国美国商会的一项调查显示,将中国视为三大投资重点之一的跨国公司比例从2012年的78%下降到2022年的45%。

中国政策环境的不确定性、跨国公司对经济增长放缓的预期以及中美经济和政治关系的整体不确定性是受访者最关心的问题。 其他担忧源于中国人口老龄化以及该国获得关键技术的限制。 来自中国国内企业的日益激烈的竞争也给跨国公司带来了挑战。

尽管存在这些担忧,但我们认为,中国仍然提供着不容忽视的机遇。

由于中国GDP占全球总量的18%,我们认为仅中国经济规模就值得跨国公司关注。 该国拥有世界上最大的中等收入阶层。 据麦肯锡预测,到2030年,超过40%至50%的中国人口将居住在高收入城市。

在汽车、奢侈品、工业设备等领域,中国市场贡献了全球收入的25%至40%。 我们认为,这使得跨国公司很难选择不参与中国市场的竞争。

英特尔首席执行官帕特·基辛格(Pat Gelsinger)承认,保持进入中国半导体市场的机会非常重要,因为它提供了收入机会,而且这些收入有助于为英特尔的研发和内部扩张提供资金。

在 7 月份阿斯彭安全论坛的主持讨论中,基辛格表示:“目前,中国占半导体出口的 25% 至 30%。 如果我的市场减少 25% 或 30%,我就需要建造更少的工厂。 我们相信,我们希望最大限度地向世界出口……您不能放弃 25% 到 30% 的市场以及世界上增长最快的市场,并期望继续为我们发布的研发和制造周期提供资金。 我们想要最大化。 目前,半导体是对中国的第二大出口产品,仅次于大豆这一战略类别,甚至没有紧随其后的第三位。 这对我们的未来具有战略意义。 我们必须继续为研发、制造等提供资金……”

为了抓住中国机遇并同时管理风险,跨国公司有多种选择来组织其供应链,例如采取“在中国,为中国”的方式,即在中国为国内市场生产零部件。 跨国公司还可以采取“中国加一”战略,在国外建立一条额外的区域供应链以到达中国及周边市场,或者维持一条以中国为组成部分的全球供应链。

扩大而不是减少贸易联系

全球供应链多元化不一定是零和游戏。

随着劳动密集型供应链从中国转移,越南、印度、柬埔寨和墨西哥等国家可能会扩大其在全球制造业中的份额。 在岸和友岸外包趋势也可能使西方的一些行业受益。

但对中国上游材料和商品的依赖意味着该国仍可能发展其制造业并向供应链上游移动。

中国继续与全球各国进行贸易,并寻求扩大贸易关系。 中国正在经历的不是“去全球化”,而是贸易流向的转变,将重点转向加强“一带一路”倡议以及与俄罗斯、中东、中亚、东盟等国家和地区的合作。 这一转变旨在减少中国对西方的依赖,扩大与更广泛的国家或全球 80% 人口的贸易关系。

话虽如此,并非所有供应链转移都一定具有成本效益。 在某些情况下,出于国家安全考虑,各国可能会建设冗余的制造能力,从而可能导致最终产品价格上涨。

例如,根据半导体研究和咨询公司 SemiAnalysis 的数据,台积电 (TSMC) 美国工厂生产的芯片可能比台湾和中国大陆生产的芯片贵 15% 至 20%。

是进化,而不是崩溃

去全球化是一个复杂的话题,最近已成为一个带有地缘政治色彩的术语。 然而,从表面上看,我们发现从 20 世纪 80 年代到 2008 年的激烈全球化时期向更加碎片化时期的转变是国际贸易和商业的自然演变。 用“供应链转型”代替“去全球化”的想法或许会更加清晰。

从概念上讲,它类似于在国家安全和主权发展优先的时期,供需的市场力量优化资源配置,找到自然平衡。 这种演变可能取决于成本、制造复杂性以及法律和政治框架等因素。

纵观现代历史,许多经济体都成功地实现了供应链转型,包括英国、美国、日本和“亚洲四小龙”(韩国、台湾、香港和新加坡)。 我们相信中国的经验不会有什么不同。

研究资源

所需披露

本文中的材料仅供参考,并不针对任何国家/地区的任何个人或实体,也不旨在向任何国家/地区的任何个人或实体分发或使用,如果此类分发或使用将违反法律或法规或将受到加拿大皇家银行的约束 或其子公司或组成业务单位(包括加拿大皇家银行财富管理公司)遵守该国家/地区的任何许可或注册要求。

这并非任何加拿大皇家银行实体出售或提供任何特定金融账户、产品或服务的具体要约,也不是申请任何特定金融账户、产品或服务的具体邀请。 加拿大皇家银行不会在不允许的司法管辖区提供账户、产品或服务,因此加拿大皇家银行财富管理业务并非在所有国家或市场都可用。

本文包含的信息本质上是一般性的,无意且不应被解释为向用户提供的专业建议或意见,也不得解释为任何特定方法的推荐。 本材料中的任何内容均不构成法律、会计或税务建议,建议您在按照本材料中包含的任何内容采取行动之前寻求独立的法律、税务和会计建议。 利率、市场状况、税收和法律规则以及与您的情况相关的其他重要因素可能会发生变化。 本材料并不旨在成为可能适合用户的方法或步骤的完整陈述,未考虑用户的具体投资目标或风险承受能力,也无意邀请进行证券交易或 以其他方式参与任何投资服务。

在法律允许的最大范围内,加拿大皇家银行财富管理公司及其任何附属公司或任何其他人均不对因使用本文件或其中所含信息而产生的任何直接或间接损失承担任何责任。 未经 RBC Wealth Management 事先同意,不得以任何方式复制或复制本材料中包含的任何内容。 RBC财富管理是描述加拿大皇家银行及其附属机构和分行财富管理业务的全球品牌名称,包括加拿大皇家银行投资服务(亚洲)有限公司、加拿大皇家银行香港分行和皇家银行 加拿大、新加坡分公司。 可根据要求提供更多信息。

加拿大皇家银行根据《银行法》(加拿大)正式成立,为股东提供有限责任。

® 加拿大皇家银行的注册商标。 经许可使用。 RBC 财富管理是加拿大皇家银行的注册商标。 经许可使用。 版权所有 © 加拿大皇家银行 2023。保留所有权利。

xxxx

China's next act in a changing economic order

https://www.rbcwealthmanagement.com/en-asia/insights/chinas-next-act-in-a-changing-economic-order

As nations move away from the post-Cold War period of intense globalization, how will the world’s manufacturing powerhouse adapt to the new economic paradigm?

By Jasmine Duan, August 14, 2023

RBC Wealth Management's “Worlds apart: Risks and opportunities as deglobalization looms” series explores the trend away from globalization and its ramifications for investors, economies, and financial markets. The latest feature in the series focuses on China’s unique role in global supply chains and manufacturing.

- A Western decoupling from China is unrealistic as supply chains are highly complex and interconnected. China is gaining market share in global manufacturing by moving up the supply chain.

- China has demonstrated an ability to overcome the impact of technological restrictions in the past. The country’s vast manufacturing scale and well-established supply chains should lay a foundation for future technological innovation.

- The country began shifting away from low-end, labour-intensive component manufacturing to higher-tech, full-spectrum product manufacturing more than a decade ago.

- China’s domestic market is too big to be ignored by multinational corporations. But we think multinationals need to determine how to pursue opportunities in China while at the same time effectively managing risks.

- The supply chain transformation we are witnessing is a natural evolution of international trade and commerce. We believe China can successfully navigate this period just as many other countries have in modern history.

News headlines often highlight the role of geopolitics and the COVID-19 pandemic in driving Western-based multinational companies to relocate their supply chains away from China. This, in turn, fuels a narrative that emphasizes these factors as the primary catalysts for change in global supply chains and China’s manufacturing sector.

As trade flows shift away from the intense period of globalization to something more fragmented, geopolitical factors are indeed playing a role. Governments are promoting and incentivizing the onshoring and friend-shoring of manufacturing, and many multinational companies are looking to diversify their supply chains.

However, for China, we think the situation is more complex and less pessimistic than mainstream headlines portray.

First, the high complexity of global supply chains, combined with the extensive scale of China’s industrial sector and manufacturing competencies, makes it undesirable and unrealistic for many multinational companies to make a complete break with China anytime soon, in our view.

Second, for years China’s manufacturing sector and global supply chains have evolved in response to forces that are unrelated to the current trade and political frictions between the U.S. and China.

Even if onshoring and friend-shoring trends pick up pace in developed countries, we think the mutually beneficial relationships that China has forged with numerous multinational companies over more than four decades will keep China integrated within the global economic and investment landscapes.

Supply chains are far more interconnected and complex than imaginable

Companies producing complex products often have four or more layers of thousands of suppliers.

According to consulting firm McKinsey & Co., technology companies have 125 tier-one suppliers (i.e., the direct suppliers of the final product or the fully built components used to create the final product) and more than 7,000 across all tiers, on average.

An auto manufacturer typically has around 250 tier-one suppliers, but the number increases to 18,000 across the full supply chain.

The complexity of global supply chains frequently results in interdependencies between companies in countries with upstream products or materials.

For example, as the 10 ASEAN* countries of Southeast Asia have built out their manufacturing competencies, they have become more connected with China’s manufacturing supply chain. ASEAN members imported US$177 billion of goods from China in 2012. In just 10 years, this more than doubled to US$388 billion by 2021.

China’s imports to ASEAN have more than doubled in the past decade

U.S. dollars (billions)

Line chart showing ASEAN countries’ import value from China for the period of 2012 through 2021. The chart shows imports steadily rising over the years and more than doubling from US$177 billion in 2012 to US$388 billion in 2021.

*The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is a regional intergovernmental organization comprising 10 member states: Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam.

Source – Statista, RBC Wealth Management; yearly data through 2021

The ASEAN region remains highly dependent on China’s inputs and capital goods, which are essential to products manufactured in those countries. If multinational companies want to produce more goods in the region in the coming years, we think Chinese production will also play a meaningful role in the supply chain.

China’s vast manufacturing footprint

The “Made in China” label is familiar to many people, yet the full scale and scope of Chinese manufacturing may still be underestimated.

Chinese manufacturing has ranked first in the world in terms of scale for over a decade. In 2021, China accounted for 30 percent of global manufacturing output, according to the UN. By comparison, the EU in aggregate accounted for 16 percent, the U.S. 15 percent, and Japan and Germany accounted for six percent and five percent, respectively.

Currently, China is the only country in the world that conforms to the standards of all manufacturing-related sections of the UN’s statistical reference classification system. This illustrates the wide breadth of China’s production capacity. Designations for many of its industries rank first in the world.

China’s rise as an intellectual property leader also contributes to the sophistication and development of its manufacturing base.

In 2019, China overtook the U.S. to become the largest source of international patents filed under the World Intellectual Property Organization’s (WIPO) Patent Cooperation Treaty.

China filed the most Patent Cooperation Treaty applications in 2022

Bar chart showing the top 10 countries filing the most patent applications under the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). Applicants from China filed 70,015 PCT applications followed by the U.S. (59, 056), Japan (50,345), the Republic of Korea (22,012), Germany (17,530), France (7,764), the UK (5,739), Switzerland (5,367), Sweden (4,471), and the Netherlands (4,092).

Source – World Intellectual Property Organization statistics database (February 2023), RBC Wealth Management

As China migrates from being a low-cost manufacturing hub to one that increasingly focuses on innovation and complex manufacturing techniques, we think the country will maintain its manufacturing dominance while at the same time make inroads into emerging and strategic fields such as electric vehicles (EV), telecommunications, bioengineering, artificial intelligence (AI), and other areas.

Manufacturing competencies have become more technologically advanced

China has established comprehensive supply chains across various industries over the past few decades, largely thanks to the localization process of multinationals and strategic joint ventures. These collaborations have enabled China to acquire technologies and know-how, and have laid the foundation for its own technological innovation.

In recent years, the West has started implementing restrictions on China’s access to critical technologies, such as AI, quantum computing, and advanced semiconductors, raising concerns about the country’s ability to move further up the supply chain and achieve its stated “technological self-reliance” goals.

This could pose challenges to China’s technology development and potentially slow it down. However, it’s important to remember that China has demonstrated an ability to overcome the impact of technological restrictions in the past. Two examples include the Tiangong space station and China’s development of EVs.

Tiangong: From the sidelines to an independent space power

The International Space Station (ISS) is a co-operative program between the U.S., Europe, Russia, Canada, and Japan. It has welcomed astronauts from 21 different countries as of June 2023.

In 2011, the U.S. Congress passed a law which was signed by the president prohibiting the country’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) from funding or engaging in direct, bilateral cooperation with China, thus effectively preventing China from joining the ISS.

In response, China spent the next decade developing and launching individual modules to complete its own permanent space station called Tiangong, or “Heavenly Palace,” in 2023.

Tiangong established China’s independent presence in space. It enables the country to conduct advanced scientific research and represents a significant, game-changing step for China as a global space power. With the ISS scheduled to be retired in 2031, Tiangong would then be the only space station in operation.

Auto industry: From nascent to high tech

A comprehensive supply chain developed over the past few decades paved the way for China’s technological advancement in the automotive industry.

The general rule of thumb is, the larger the production scale in a particular manufacturing segment, the easier it is to improve production efficiency, product quality, and technology.

China has sought to overcome technology hurdles by putting in place national policies and capital support, nurturing domestic talent, and forming strategic, mutually beneficial alliances with other nations.

China’s development of its automotive industry, particularly its rapid progress in EV technology, provides insights into the country’s ability to scale up production into higher-tech manufacturing.

The auto sector in China saw rapid growth after the government’s Reform and Opening-up period in the late 1970s and 1980s. The industry formed joint ventures with foreign automakers such as Volkswagen, General Motors, and Honda.

At first, China’s auto industry relied heavily on foreign technologies, particularly when it came to engines and transmission designs – core components of internal combustion vehicles.

Over time, China developed extensive auto supply chains and manufacturing capacity, while actively encouraging the development of skilled engineering talent.

By the early 2000s, China started to explore alternative energy vehicles. In the 2010s, the government introduced a series of policies designed to support research and development (R&D) and encourage EV adoption.

Many of the technologies and production techniques used in traditional vehicle production can be transferred to EV manufacturing. At the same time, the core components and technologies of an EV include the battery, electric motor, and electronic control system, which vary greatly from the components that make up a traditional vehicle with an internal combustion engine.

With robust manufacturing know-how and supportive public incentives, China’s automotive industry was able to free itself from the technological constraints of traditional fossil fuel drivetrains and make inroads into more advanced, cleaner technologies.

A recent report from Patent Result highlights China’s lead in EV charging patents. From 2010 to 2022, Chinese companies submitted 41,011 patent applications in this field, which is 52 percent higher than that of Japan and nearly three times the number of U.S. EV charging patents. China has now become the largest exporter of new EVs, overtaking Japan, the U.S., and Europe.

China’s shift away from labour-intensive manufacturing

Other factors that have little to do with the current geopolitical frictions between the U.S. and China have also helped to transform Chinese supply chains and manufacturing processes. These mostly stem from China’s own economic development.

Over the past 20 years as China’s economy has grown markedly, labour costs have more than doubled, forcing labour-intensive industries such as footwear and apparel manufacturing to relocate to countries with more affordable labour – in many cases to ASEAN countries.

This process can be traced back to when China began upgrading its manufacturing sector more than a decade ago.

Some labour-intensive industries began to move away from coastal manufacturing hubs into less developed inland cities and provinces.

Later, as labour costs increased there as well, production began migrating abroad with Chinese-owned factories popping up in ASEAN countries. The range of Chinese manufacturing investments in the region includes textiles, consumer electronics, EV supply chains, pharmaceuticals, and others.

As of 2021, China has become the third-largest international source of foreign direct investment in the ASEAN region at US$14 billion, following the U.S.’s US$40 billion and the US$21 billion that ASEAN countries invest in each other.

Supply chain diversification: Less than what is advertised

Although there has been some degree of supply chain diversification away from China, this change is not as significant as one might assume. A good example comes from the electronics and machinery sector, which is the largest goods category in global trade.

The sector is dominated by China in exports but has been shifting somewhat to ASEAN countries in recent years. China’s electronic exports by value to the U.S. decreased by 10 percentage points from 2018 to 2021. Most of the slack was taken up by ASEAN countries, according to a study by Macro Polo, a U.S.-based think tank connected to the Paulson Institute (founded by former U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson).

One may easily draw the conclusion that China has been losing ground to ASEAN countries in global manufacturing. However, the data tell a different story. ASEAN countries’ gains in global manufacturing are comparatively minor; the region’s market share climbed slightly from around three percent in 2010 to about five percent by 2021, while China’s share rose from 20 percent to 30 percent over the same period.

The data indicate to us that while some of the final assembly of manufactured products may have shifted from China to ASEAN, China’s overall manufacturing capacity has remained elevated.

China has been gradually replacing labour-intensive industries with more advanced and higher value-added manufacturing. Prime examples of this structural transformation are the export boom of three renewable energy products: new energy vehicles, solar cells, and lithium batteries.

As China moves up the supply chain, its economy is becoming more complex

Harvard Economic Complexity Index rankings; “1” is the most complex

Line chart showing various countries’ (Japan, the U.S., China, Mexico, India, and Vietnam) complexity rankings from 1995 to 2020. Japan has been ranking first in the index since 1995. China’s ranking improved to 18th in 2020 from 46th in 1995. The U.S.’s ranking has trended slightly down over the years and ranked 14th in 2020, while Mexico was 29th in 1995 and rose to 20th in 2020. India’s and Vietnam’s rankings increased from 60th to 46th and from 107th to 57th, respectively.

- Japan

- U.S.

- China

- Mexico

- India

- Vietnam

Note: Economic development requires the accumulation of productive knowledge and its use in a wider range of more complex industries. The Harvard Growth Lab’s Economic Complexity Index (ECI) assesses the state of a country’s productive knowledge. As the number and complexity of a country’s exports increase, the country’s ECI moves toward “1”; for example, in this data, Japan has consistently had the highest ECI of 1, whereas Vietnam currently has the lowest at 57, although its score has been improving.

Source – Harvard Growth Lab, RBC Wealth Management

Simultaneously, China has shifted its trade model away from processing trade, which relies on supplied materials or components. Processing trade has historically been used by manufacturers seeking access to specialized inputs or lower labour costs. Its share in China’s total exports has decreased to around 20 percent, down from 55 percent in 2000. At the same time, finished goods export unit values have continued to rise, signaling an ongoing industrial upgrade.

As Chinese manufacturing has become more complex, the value of vehicle exports has surged

U.S. dollars (millions)

Line chart showing China’s monthly export value of mobile phones and vehicles from May 2020 through May 2023. In May 2020 vehicle exports totaled US$1,305 million and they have been increasing (last reading was US$7,758 million). Vehicle export value has now caught up with that of mobile phones (last reading was US$8,101 million), traditionally an important export segment.

- Mobile phones

- Vehicles

Source – RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; monthly data through June 2023

Will China remain an attractive investment destination?

China and multinational corporations built mutually beneficial relationships after the country’s Reform and Opening-up period in the 1970s and 1980s. China acquired technology and management know-how from multinationals, while these companies enjoyed low production costs in China and higher profits (which we think boosted stock prices), as well as access to China’s large domestic market.

However, more recently, multinationals have begun reassessing the business environment and their investment plans in China.

In a survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, the share of multinational corporations perceiving China as one of their top three investment priorities dropped from 78 percent in 2012 to 45 percent in 2022.

Uncertainty around China’s policy environment, multinationals’ expectation of slower economic growth, and overall uncertainty about the U.S.-China economic and political relationship were the top concerns of survey respondents. Other concerns stem from China’s aging demographics and the country’s restricted access to key technologies. Rising competition from Chinese domestic players also poses challenges to multinationals.

Despite these concerns, in our view, China still presents opportunities that cannot be ignored.

With its GDP accounting for 18 percent of the global total, we think the size of China’s economy alone demands attention from multinationals. The country has the world’s largest middle-income class. Based on McKinsey’s estimates, more than 40 percent to 50 percent of China’s population will live in high-income cities by 2030.

In sectors such as automobiles, luxury goods, and industrial equipment, China’s market contributes 25 percent to 40 percent of global revenues. In our view, this makes it hard for multinational corporations to choose to not compete in the Chinese market.

Intel’s CEO Pat Gelsinger has acknowledged that maintaining access to China’s semiconductor market is very important due to the revenue opportunities and because that revenue helps fund Intel’s R&D and internal expansion.

During a moderated discussion at the Aspen Security Forum in July, Gelsinger said: “Right now, China represents 25 to 30 percent of semiconductor exports. If I have 25 or 30 percent less market, I need to build less factories. We believe we want to maximize our exports to the world … You can’t walk away from 25 to 30 percent and the fastest growing market in the world and expect that you remain funding the R&D and the manufacturing cycle that we’ve released. We want to maximize. And right now semiconductors are the number two export to China behind that strategic category of soybeans, and there’s not even a close number three. This is strategic to our future. We have to keep funding the R&D, the manufacturing, et cetera …”

To capture opportunities in China and manage risks at the same time, multinationals have various options to organize their supply chains, such as adopting an “in China, for China” approach, where components are manufactured in China for its domestic market. Multinationals could also adopt a “China plus one” strategy, by establishing an extra regional supply chain outside of the country to reach China and surrounding markets, or by maintaining a global supply chain utilizing China as one component.

Expanding, not reducing, trade ties

Global supply chain diversification doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game.

With labour-intensive supply chains shifting away from China, countries such as Vietnam, India, Cambodia, and Mexico could expand their shares of global manufacturing. The onshoring and friend-shoring trends are also likely to benefit some industries in the West.

But the dependency on China’s upstream materials and goods means the country can likely still grow its manufacturing sector and move up the supply chain.

China continues to trade with countries globally and seeks to expand trade ties. Rather than “deglobalizing,” China is experiencing a shift in trade flows, adjusting its focus towards strengthening its Belt and Road Initiative and cooperation with countries and regions including Russia, the Middle East, Central Asia, and ASEAN. This shift aims to reduce China’s reliance on the West and expand trade ties with a broader range of countries, or the 80 percent of the rest of the global population.

Having said that, not all supply chain shifts will necessarily prove cost-effective. In some cases, countries might construct redundant manufacturing capacities driven by national security concerns, potentially resulting in increased end-product prices.

For example, chips made in Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s (TSMC) U.S. factory are likely to be 15 percent to 20 percent more expensive than those made in Taiwan and China, according to semiconductor research and consulting firm SemiAnalysis.

An evolution, not a breakdown

Deglobalization is a complicated topic, and recently has become a geopolitically loaded term. However, beneath the surface, one finds that the shift away from the period of intense globalization that occurred from the 1980s through 2008 to something more fragmented is a natural evolution of international trade and commerce. Substituting the idea of “supply chain transformation” for “deglobalization” perhaps provides more clarity.

Conceptually, it is akin to the market forces of supply and demand optimizing the allocation of resources to find a natural equilibrium in a period in which national security and sovereign development are being prioritized. The evolution could depend on costs, manufacturing complexity, as well as legal and political frameworks, among other factors.

Throughout modern history, many economies have successfully navigated supply chain transformation including Great Britain, the U.S., Japan, and the “Four Asian Tigers” (South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore). We do not believe the China experience will prove to be any different.

The material herein is for informational purposes only and is not directed at, nor intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity in any country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Royal Bank of Canada or its subsidiaries or constituent business units (including RBC Wealth Management) to any licensing or registration requirement within such country.

This is not intended to be either a specific offer by any Royal Bank of Canada entity to sell or provide, or a specific invitation to apply for, any particular financial account, product or service. Royal Bank of Canada does not offer accounts, products or services in jurisdictions where it is not permitted to do so, and therefore the RBC Wealth Management business is not available in all countries or markets.

The information contained herein is general in nature and is not intended, and should not be construed, as professional advice or opinion provided to the user, nor as a recommendation of any particular approach. Nothing in this material constitutes legal, accounting or tax advice and you are advised to seek independent legal, tax and accounting advice prior to acting upon anything contained in this material. Interest rates, market conditions, tax and legal rules and other important factors which will be pertinent to your circumstances are subject to change. This material does not purport to be a complete statement of the approaches or steps that may be appropriate for the user, does not take into account the user’s specific investment objectives or risk tolerance and is not intended to be an invitation to effect a securities transaction or to otherwise participate in any investment service.

To the full extent permitted by law neither RBC Wealth Management nor any of its affiliates, nor any other person, accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this document or the information contained herein. No matter contained in this material may be reproduced or copied by any means without the prior consent of RBC Wealth Management. RBC Wealth Management is the global brand name to describe the wealth management business of the Royal Bank of Canada and its affiliates and branches, including, RBC Investment Services (Asia) Limited, Royal Bank of Canada, Hong Kong Branch, and the Royal Bank of Canada, Singapore Branch. Additional information available upon request.

Royal Bank of Canada is duly established under the Bank Act (Canada), which provides limited liability for shareholders.

® Registered trademark of Royal Bank of Canada. Used under license. RBC Wealth Management is a registered trademark of Royal Bank of Canada. Used under license. Copyright © Royal Bank of Canada 2023. All rights reserved.