insight

工程技术,地产投资,信仰家园,时尚生活Published: 20 November 2012 (GMT+10)

On 14th May 2012, the Dalai Lama was awarded the Templeton Prize of £1.1 million.1 So what is the Templeton Prize, and why did the Dalai Lama get it?

The 14th Dalai Lama

The Templeton Prize

The Templeton Prize was established in 1972 by American-born British billionaire Sir John Marks Templeton (1912–2008), who later set up the Templeton Foundation to fund the prize in perpetuity. This came to our attention a decade ago when we learned that the Templeton Foundation was paying Bible colleges around the world to run courses that taught theistic evolution. See Evangelical colleges paid to teach evolution. At that time the Templeton website said its Prize was awarded annually to

“a living individual who has shown extraordinary originality advancing the world’s understanding of God and/or spirituality.”2

“The Prize is intended to help people see the infinity of the Universal Spirit still creating the galaxies and all living things and the variety of ways in which the Creator is revealing himself to different people. We hope all religions may become more dynamic and inspirational.”3

After Sir John’s death, the revised Templeton website read:

“The Prize celebrates no particular faith tradition or notion of God, but rather the quest for progress in humanity’s efforts to comprehend the many and diverse manifestations of the Divine.”4

As such, the website announces that its Prize has been awarded to “representatives of Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism, but also others as well”, i.e. to those who do not claim adherence to any of these religions. See Templeton Prize goes to evolutionist professor, and Templeton Prize goes to pantheist Darwinist.

The Templeton website originally said: “The Templeton Prize does not encourage syncretism … .” However, the awarding of the Prize this year would seem to be the epitome of this. The Dalai Lama is a ‘Buddhist atheist’ (he says he’s Buddhist, and that he doesn’t believe in God; hence ‘Buddhist atheist’). The website says he

“has vigorously focused on the connections between the investigative traditions of science and Buddhism as a way to better understand and advance what both disciplines might offer the world.”5

Nevertheless the presentation ceremony was held in St Paul’s Cathedral, London. It was preceded by a period of chanting by eight Buddhist monks, before he was welcomed by the Canon of St Paul’s, with the Bishop of London and the Archbishop of Canterbury in support.

The Dalai Lama

The 14th Dalai Lama6 is a man by the name of Tenzin Gyatso (né Lhamo Dondrub, 1935– ). Since 1950, he has been the leader of the dominant sect of Tibetan Buddhists, who believe him to be a reincarnation of an ancient Buddhist leader, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.7 However, concerning himself, the Dalai Lama says: “I am just a human being.”8

In 1950, Communist China took over Tibet. After the Communists brutally crushed a Tibetan uprising in 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India. He was awarded the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize “in recognition of his nonviolent campaign over nearly 40 years to end China’s domination of his homeland”.9 He is the first Dalai Lama to have come into full contact with Western science and technology.

He has written some 70 books in which he reiterates that as a Buddhist he does not believe in a transcendent Creator God who is the uncaused first cause, nor that Jesus Christ was this God incarnate. He thus does not believe that mankind is in rebellion against God and hence under divine Judgment from which we need a Saviour, or that Jesus Christ is that Saviour. He tells us: “My own worldview is grounded in the philosophy and teachings of Buddhism, which arose within the intellectual milieu of ancient India.”10,11

Buddhism is a philosophy of life, the product of human thought, not a revelation from God or about God.

Origin of Buddhism

Buddhism began as the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, a Hindu prince of the Sakya tribe, born in northern India (now Nepal), who lived and died 25 centuries ago. At the age of 29, he ventured beyond the protective walls of the palace and saw for the first time a frail old man, a sick person, a dead body, and an ascetic. All this led him to abandon his kingly birthright, leave the palace and his wife of 13 years and his newborn son, and give himself to extreme asceticism, which almost cost him his life. He then chose a ‘middle path’ that avoided both self-mortification and self-indulgence, and which culminated for him in ‘enlightenment’ through meditation. He became known as Sakyamuni Buddha—meaning ‘the sage of the Sakyas’, or just ‘the Buddha’, meaning ‘the enlightened one’.

This does not mean he was a god, or a messenger/prophet from God. The Buddhist website buddhanet.net states: “A Buddha is not a god/God. The relationship between a Buddha and his disciples and followers is that of a teacher and student.”12 Buddhism is thus a philosophy of life, the product of human thought, not a revelation from God or about God. Buddhist doctrine is known as the Dharma.

The Buddha’s ‘enlightenment’ included the Four Noble Truths. These are:

- Life is suffering.

- The origin of suffering is desire arising from greed, anger and ignorance.

- Cessation from suffering is possible.

- This can be achieved by following the Noble Eightfold path of right living through self-effort.13

Karma

The concept of karma as a universal Law of Cause and Effect pervades Buddhism. Buddhist Venerable Master Hsing Yun explains:

These ladies believe they can earn good karma by giving food each day to Buddhist monks.

“All intentional acts of body, speech, and mind produce karmic retribution that will inevitably occur. … it is karma that keeps sentient beings trapped in the cycle of birth and death. … Good karma [resulting from deeds which help other sentient beings] leads to rebirth as a human being or a heavenly being. On the other hand, bad karma is any action that harms or causes suffering to self or others. Very bad acts produce karma that leads to rebirth in one of the three lower realms of existence (the realms of hell, hungry ghosts, and animals).”14,15

And the Dalai Lama says:

“In Buddhism, this karmic causality is seen as a fundamental natural process and not as any kind of divine mechanism or a working out of a preordained design.”16

Karma generated in this life may arrive in this life, or in the next life, or in some life beyond the next life “when the right conditions arise”. Karmic causes and effects do not disappear, they cannot be forgiven, there are no exceptions, and bad karma and good karma cannot cancel each other out. One life is not enough to pay for all of one’s karma. Reincarnation is thus an ongoing process of birth, death, and rebirth … with the prospect that if you kill a chicken in this life, you face being reborn as a chicken in your next life (see also Reincarnation vs Creation). Strict Buddhism calls for vegetarianism, because eating meat involves killing an animal. Westerners might wonder whether another reason could be the possibility that a frozen chicken in a supermarket just might be Grandpa!

Nirvana

For Buddhists, the only means of escaping from this cycle is to achieve nirvana. According to Buddhist authorities, this is not a heaven or paradise, but more like total oblivion.

“In Buddhism, it refers to the absolute extinction of individual existence, or of all afflictions and desires; it is the state of liberation, beyond birth and death. It is also the final goal of Buddhism.”17

Achieving nirvana is through enlightenment, which means that you become a buddha, i.e. someone who has been purified of karma. This is only possible from the human realm. No saviour exists, not even Buddha. Each person must get there solely by their own effort.

Some aspects of Buddhism vis-à-vis Christianity

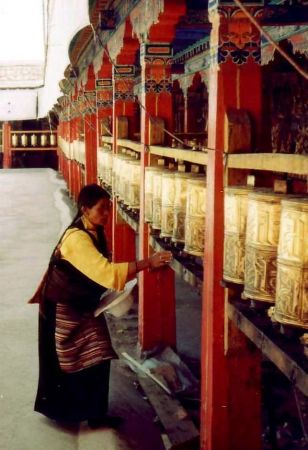

Buddhists don’t pray to God, but believe they can earn merit by turning a prayer wheel as this woman is doing, while reciting the mantra written on it.

1. No God

Buddha rejected the existence of all gods and spiritual beings. Buddhism thus denies the Christian concept of a Supreme Spiritual Being outside of His creation who brought all things into existence. Buddhists begin with the presupposition that there is no Divine Authority to direct their conduct or to whom they are accountable now or in any future life.

Christianity’s presupposition is that God does exist as a Personal, Intelligent, Moral Being. We believe that He is able to communicate truth to us and has done so in His Word, which we call the Holy Bible. In this, God tells us not only that He created all things, but that He did so through his Son, the Lord Jesus Christ (Colossians 1:16). And concerning our accountability to God, we are assured that not only is it appointed unto man to die only once, but “after that comes judgment” (Hebrews 9:27).

2. No non-material part of man that survives physical death

The Dalai Lama writes:

“In Buddhism there is no recognition of something like the soul which is unique to humans. From the perspective of consciousness, the difference between humans and animals is a matter of degree and not of kind.”18

Christians believe that because we are all “made in the image of God”, we have a spiritual dimension, i.e. a capacity for holding spiritual communion with God through prayer, praise, and worship. Furthermore this is a permanent essence or immortal part of man that survives death; it is sometimes called the “soul” (Matthew 10:28); cf. Revelation 6:9 where the martyred disembodied dead in heaven are called “souls”. And Jesus said: “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul” (Mark 8:36).

These aspects of ‘no God’ and ‘no soul’ are similar to atheist/evolutionist Richard Dawkins’ statement in The God Delusion:

“An atheist … is somebody who believes there is nothing beyond the natural, physical world, no supernatural creative intelligence lurking behind the observable universe, no soul that outlasts the body and no miracles—except in the sense of natural phenomena that we don’t yet understand.”19

To the Western mind, the doctrine of ‘no soul’ appears to undermine the Buddhist concept of reincarnation—if a person has no soul, what part of them gets reborn? And without a soul how can anyone be held accountable for karma and its alleged consequences? However, to a Buddhist, religion is a set of practices not a set of answers. Relating harmoniously to everyone and everything is more important than the reason why things are or are not.

3. No sin against God

Sin, as rebellion against a holy God, or as transgression of divine law(s), is not recognized in Buddhism. Buddhists have many numerical lists of things to do or not do, but these tend to be regarded more as counsel than as commandments. For example, one of Buddha’s Five Precepts for laymen is “Do not take intoxicants.”20 Thus under Buddhist philosophy, if you do drink alcohol or use drugs, you are just making it harder for yourself to become enlightened. Equally, sexual misconduct is not a sin in the sense of breaking a God-given commandment.

Christianity teaches that sin is rebellion against the authority of God over us, and against His standards for our behaviour. As such sin is an affront to the holiness of God who made us “in His image” (Genesis 1:27).21 (See Why did God impose the death penalty for sin? and Dawkins’ dilemma: How God forgives sin). Jesus said that the work of the Holy Spirit is to “convict the world of sin, and of righteousness and of judgment” (John 16:8).

4. No Saviour

In Buddhism, there is no Saviour. The only salvation is through self-help, following the ‘Noble Eightfold Path’ until you become a buddha, i.e. you pass out of the wheel of life and enter nirvana. Buddhists deny the deity of Jesus Christ, and hence that His death on the cross was the perfect sacrifice and atonement for our sins.

The Gospel, as defined in 1 Corinthians 15:1–4, is “that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures.” The Bible says that by His resurrection from the dead Christ “was declared to be the Son of God in power” (Romans 1:4). The Lord Jesus Christ is thus the Saviour whom God has provided and whom we all need. As the Bible says: “In this is love, not that we have loved God but that He loved us and sent His Son to be the propitiation for our sins” (1 John 4:10).

5. No creation—either of life or of the universe

(a) Of Life

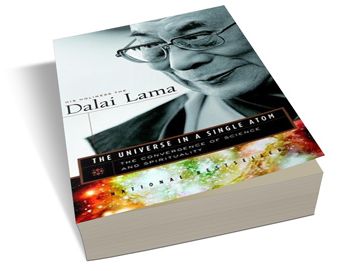

In his book The Universe in a Single Atom the Dalai Lama devotes the whole of Chapter Five to discussing the theory of evolution. As this concept is not a threat to any Buddhist scriptures, nor yet to the Buddhist religion, and certainly not to Buddhist atheism, his conclusions are very pertinent and obviously he cannot be accused of having a creationist bias.

He notes that Darwinian evolution does not explain the origin of life, that it is not even a testable theory by Karl Popper’s definition (see creation.com/its-not-science), that survival of the fittest is a tautology, that the struggle for existence through aggression and competition does not explain altruism and compassion, and that the Darwinian account of the origin of life does not explain the origin of sentience (i.e. conscious beings who have the capacity to experience pain and pleasure).22

Not surprisingly, because he does not believe in Creation, the Dalai Lama does not have an adequate answer to any of the problems he highlights in Darwinism.

(b) Of the Universe

Buddhism provides no historical information about the beginning of things—the universe, the world, life, us. Despite their obsession with the karmic law of cause and effect, the issue of a ‘First Cause’ is cheerfully and robustly ignored. In his book, The Universe in a Single Atom, the Dalai Lama writes:

“From the Buddhist perspective, the idea that there is a single definite beginning is highly problematical. If there were such an absolute beginning, logically speaking, this leaves only two options. One is theism, which proposes that the universe is created by an intelligence that is totally transcendent, and therefore outside the laws of cause and effect. The second option is that the universe came into being from no cause at all. Buddhism rejects both these options.”23

He notes the promotion of the big bang as an attempt by some to explain the origin of the universe, but finds the latter unconvincing. He says:

“I am left with questions, serious ones: What existed before the big bang? Where did the big bang come from? What caused it? Why has our planet evolved to support life? What is the relationship between the cosmos and the beings that have evolved within it?”24

He concludes: “[I]n Buddhism the universe is seen as infinite and beginningless … ”25 He also points out that the Buddha himself never directly answered questions put to him about the origin of the universe. And he says that

Yes, even in India we look both ways before we cross the street because it is either me or the bus, not both of us.

“Interpretations of the meaning of the Buddha’s refusal to answer these questions directly vary. One view is that the Buddha refused to answer because these metaphysical questions do not directly pertain to liberation [i.e. release into nirvana]. Another view … is that insofar as the questions were framed on the presupposition of the intrinsic reality of things, and not on dependent origination, responding would have led to a deeper entrenchment in the belief in solid, inherent existence.”26

This mention of the ‘reality of things’ highlights the Buddhist doctrine that reality is an illusion, and that all things and experiences are changeable and impermanent. As Buddhist Venerable Master Hsing Hun explains:

“In Buddhism it is said that existence relies on emptiness, which means that all phenomena have no ‘independent’ nature. Since all things are interconnected, not one of them can be said to have a permanent, substantial existence. Ultimately, the nature of all things is ‘empty’; their existence relies on ‘emptiness’.”27

Presumably such a thought experiment does not preclude Buddhists from looking both ways before crossing a busy street. The leading Indian-born Christian apologist Ravi Zacharias (1946– ) says:

“Yes, even in India we look both ways before we cross the street because it is either me or the bus, not both of us!”28

Concerning reality, Christians believe in a God who not only is there, but who also has given us accurate information about the past. As Christian scholar and theologian Dr Francis Schaeffer has said: “He [God] has spoken first about Himself, not exhaustively but truly; and second, He has spoken about history and about the cosmos, not exhaustively but truly.”29 Our record of this is the Bible.

What then do Buddhism and Christianity say about the three major concerns that human beings have concerning life? Consider:

BUDDHISM | CHRISTIANITY | |

|---|---|---|

God | Unknowable | Revealed in the Bible |

Soul | None | Immortal part of man |

Sin | Replaced by the Law of Karma | Rebellion against God |

Saviour | Only one’s own self | Jesus Christ, the one and only |

Salvation | Through ‘enlightenment’ | Through repentance and faith in Christ’s death and resurrection |

Goal | Achieving an unconscious nirvana | To live forever with Christ in Heaven |

1. Forgiveness for the past

Buddhists do not acknowledge that humans are in rebellion against a holy God. They are accountable only to themselves and so only have themselves to save themselves by their own works. The result of this mindset is that they have no basis for forgiveness for shameful deeds done in the past, only a wretched proactive inescapable karma.

The good news for Christians (and indeed for everybody) is that there is an answer to the sin problem. It is called salvation. We believe that God loves us (Romans 5:8), and because He loves us, He sent his Son, the Lord Jesus Christ, who had no sin (Hebrews 4:15), to pay the penalty for our sins by His death on the cross. “In Him we have redemption through His blood, the forgiveness of sins” (Ephesians 1:7). Because Christ was sinless, He could die for our sins, and because He was and is God, His death is effective for all who avail themselves of it by repentance and faith in what He has done.

The Bible says: “If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9). Notice the word “just”—God can justly forgive us our sins because Christ has paid the penalty for them. And it is only on the grounds of Christ’s death on our behalf that God can and does deal mercifully with us. The Bible also says: “For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast” (Ephesians 2:8–9).

2. Help for the present

We have already seen that Buddhism offers no help for the present. Their cure for suffering is the elimination of desire, but counteracting this ‘cure’ is the doctrine of karma. There is also the problem of self-refutation: there must be a desire to eliminate desire! Christianity teaches that the greatest problem we all have is sin, and a primary meaning of this is “missing the mark” or “falling short” (meaning “falling short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23)).30 Buddhists may think of this only in terms of their ongoing Law of Cause and Effect, or karma, but the Bible calls it ‘sin’.

The good news of the Gospel is that “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, ‘Cursed is everyone who is hanged on a tree’” (Galatians 3:13). While this is referring to our transgression against God’s Law, Christ can save Buddhists not only from this, but also from their own self-imposed Law of Karma because “as far as the east is from the west, so far does He remove our transgressions from us” (Psalm 103:12).

When Christ rose from the dead, He was resurrected as Himself, not reincarnated as somebody else. As such, He dwells in the hearts of believers through faith (Ephesians 3:17). The Bible calls this being ‘born again’ (John 3:3), and the especially good news for Buddhists is that it only needs to happen once. Further good news is that the same almighty power of God that raised Christ from the dead is available to Christians today for life and service (Ephesians 1:18–20). But the corresponding bad news for the unsaved is that we only “die once, and after that comes judgment” (Hebrews 9:27)—no second chances in a reincarnated future life.

3. Hope for the future

For Buddhists, the future means innumerable rebirths, with the forlorn hope of perhaps achieving nirvana—something like total annihilation—at absolute best. Not much of a future!

For Christians, the future means hope—a hope that is certain. We have the wonderful promise that after death we will be united with our God and Saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ, to spend eternity with Him in Heaven. The Word of God, the Bible, referring to those who have died as those who have ‘fallen asleep’, says:

“But we do not want you to be uninformed, brothers, about those who are asleep, that you may not grieve as others do who have no hope. For since we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so, through Jesus, God will bring with Him those who have fallen asleep. For this we declare to you by a word from the Lord, that we who are alive, who are left until the coming of the Lord, will not precede those who have fallen asleep. For the Lord himself will descend from heaven with a cry of command, with the voice of an archangel, and with the sound of the trumpet of God. And the dead in Christ will rise first. Then we who are alive, who are left, will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air, and so we will always be with the Lord” (1 Thessalonians 4:13–18).

Thus, Christ’s atoning death and His resurrection not only provide cleansing from shame in the past, they also give power in the present, and certain hope for the future.

Evangelizing Buddhists

Buddhism produces a strong national and ethnic identity which is one of the greatest obstacles to evangelism. In the minds of many Asians, to be Thai, Burmese, Tibetan … etc. is to be Buddhist. Thus, as in all evangelism, one must build bridges, i.e. be a caring friend who forms trusting relationships. We also need to bear in mind that it will be much easier for converts to stand if the whole family comes to Christ rather than just individuals.

Dr Alex Smith, OMF International missionary with many years experience relating to missionary evangelism of Buddhists advises:31

- Clarify essential concepts

Such as the universe, God, Christ, man, sin, grace, salvation, life, Heaven. These terms all mean something different to Buddhists from what they mean to Christians.

- Check they heard what you meant

Good communication depends on what has been heard and understood rather than on what has been said. So conversational exchange involving listening and feedback to clarify meaning are essential. E.g. ‘eternal life’ (John 3:16) may be understood by Buddhists to mean ‘eternal suffering’ because to them life is suffering and they make every effort to escape ‘the inevitable cycle of ongoing life’.

- Have confidence that God is working

The Holy Spirit is the primary agent for producing conviction and conversion. The powerful Word of God proclaimed, clearly understood, and received by faith can transform lives, families, societies, and whole people groups.

- Practise love and patience

Pray, earn the right to speak, relate in true Christian love and genuine affection, avoid criticism and pressure, believe that God is working.

Some different approaches to sharing the Gospel with Buddhists suggested by Dr Smith include:32

- Begin with God as Creator as does the Bible (but explain that suffering is due to the rebellious choice of humans).

- Use elements of Buddhism as stepping stones to Christianity—presenting the exact truth of God but in meaningful garb. E.g. the curse of karma is done away with through Christ’s redemptive death and resurrection.

- Explain repentance and forgiveness in terms of deliverance from shame rather than just from guilt. (The Bible mentions shame many times more often than it does guilt. And Asian cultures are more shame-driven than Western ones, which are more guilt driven.)

- Show that the Gospel can deliver healing in place of suffering.

- Show that Christ is the all-powerful Lord over the things that Buddhists fear, such as animistic spirits, ancestral ghosts, witchcraft, the afterlife, the eight levels of Buddhist hells, and especially the impact of their karma.

- And remember that “Truly, above everything else, the mighty power of Christ in our lives is the crucial dynamic that will help Buddhists recognize the living Creator God.”33

The first book in the Bible, Genesis, relates how suffering and death entered the world. God originally created a perfect sinless world, in which there was no violence, disease, suffering, or death (Genesis 1:31). However, the first humans whom God created, Adam and Eve, rejected God’s authority over them, thereby incurring God’s righteous judgment. This judgment included suffering as well as death. Thus Genesis 3:16–19 reads:

“To the woman He said, ‘I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children. Your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.’ And to Adam He said, ‘Because you have listened to the voice of your wife and have eaten of the tree of which I commanded you, “You shall not eat of it,” cursed is the ground because of you; in pain you shall eat of it all the days of your life, thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; for you are dust, and to dust you shall return.’”

As well as judging sin with death, God also withdrew some of His sustaining power. Everything is thus running down because of sin (“in bondage to decay”, Romans 8:19–22).34 God has given us a taste of life without Him—we now live in a world of violence, disease, suffering, and death—and the whole cosmos was affected, including animals eating each other, and thorns. Christians are not immune from these, and the Gospel does not promise we shall be delivered from suffering. Indeed, God Himself, in the person of Jesus Christ, went through pain, suffering and death to redeem us from eternal suffering. Rather, God has purposes to achieve in our life through suffering. And for this, we as Christians now have Christ’s presence within us (John 1:12) to help us.

In particular: Suffering can ‘perfect’ us, or make us mature in the image of Christ (Romans 5:3–5; Hebrews 5:7–9). Suffering can help us to know Christ who was a “man of sorrows and acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:3). Suffering can make us more able to comfort others who suffer. (2 Corinthians 1:3–4). Suffering prepares us for glory in heaven (Romans 8:18; 2 Corinthians 4:17). And as Christians we should especially note Philippians 1:29: “For it has been granted to you that for the sake of Christ you should not only believe in Him but also suffer for His sake.”

Related articles

References

- Most of which he said he planned to donate to the Save the Children fund in India, and to a project to train Buddhist monks as scientists. Return to text.

- www.templetonprize.org/purpose.html accessed 23 January 2002. Return to text.

- www.templetonprize.org/purpose.html accessed 14 February 2002. Return to text.

- www.templetonprize.org/purpose.html accessed 27 August 2012. Return to text.

- www.templetonprize.org accessed 9 October 2012. Return to text.

- ‘Dalai Lama’ is a title meaning literally ‘ocean teacher’ or figuratively ‘teacher of deep concepts’. Return to text.

- Bodhisattvas are believed by Tibetan Buddhists to be enlightened beings who have postponed their own nirvana and chosen to take rebirth in order to serve humanity. The first Dalai Lama was Gendun Drup (né Pema Dorje, 1391–1474). Return to text.

- The Dalai Lama, My Spiritual Autobiography, p. 7, Rider, London, 2010. Return to text.

- The New York Times online, October 6, 1989. Return to text.

- The Dalai Lama, The Universe in a Single Atom, p. 43, Broadway Books, New York, 2005. Return to text.

- Today Buddhism has over 1 billion followers worldwide, and involves many sects within its main traditions, which are: the conservative Theravada known as Southern Buddhism (e.g. in Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos), the more liberal and majority Mahayana known as Northern and Eastern Buddhism (e.g. in Japan, China, Korea), and the more recent (c. 7th to 8th century AD) minority Vajrayana that contains some tantric elements, practised mostly in Tibet and Mongolia. Zen is the Japanese term for a form of Mahayana Buddhism that emphasizes knowledge achieved through meditation, rather than theoretical knowledge as the route to enlightenment. Return to text.

- buddhanet.net/e-learning/snapshot01.htm Return to text.

- The Noble Eightfold path involves “(1) Right View; (2) Right Thought; (3) Right Speech; (4) Right Action; (5) Right Livelihood; (6) Right Effort; (7) Right Mindfulness, and (8) Right Concentration.” (Ref. 14, p. 136.) Return to text.

- Venerable Master Hsing Yun, The Core Teachings Buddhist Practice and Progress 1, pp. 35–36, Buddha’s Light Publishing, CA 91745, USA, 2006. Return to text.

- Some writers use the term ‘merit’ for ‘good karma’. Return to text.

- Ref. 10, p. 109. Return to text.

- Ref. 14, p. 135. Return to text.

- Ref. 10, p. 107 Return to text.

- Dawkins, R., The God Delusion, Bantam Press, London, 2006, p. 14. See refutation by Bell, P., J. Creation 21(2):28–34, 2007; creation.com/delusion. Return to text.

- “Five Precepts: The fundamental principles of conduct and discipline that were established by the Buddha for wholesome and harmonious living. They are: 1) do not kill; 2) do not steal; 3) do not lie; 4) do not engage in sexual misconduct; and 5) do not take intoxicants.” Quoted from Ref. 14, p. 133. Return to text.

- Cosner, L., Broken images, Creation 34(4):46–48, 2012. Return to text.

- Ref. 10, pp. 111–115. See also review of this book by Bergman, J., Dalai Lama—Nobel laureate Darwinism critic, J. Creation 26(3), 2012 (in press). Note too Buddhist Venerable Master Hsing Yun’s comment on the Law of Cause and Effect: “If you plant a pumpkin seed, you will not reap a tomato.” (Ref. 14, p. 19.). Return to text.

- Ref. 10, p. 82. Return to text.

- Ref. 10, p. 92. Return to text.

- Ref. 10, p. 93. Return to text.

- Ref. 10, p. 77. Return to text.

- Ref. 14, p. 19. Return to text.

- From the article “Proven Western Logic vs. Flawed Eastern Logic” at forums.canadiancontent.net/. See also Kumar, S., and Sarfati, J., Christianity for Skeptics, ch. 7, Creation Book Publishers, 2012. Return to text.

- Schaeffer, F., A Christian View of Philosophy and Culture, Book 3, He Is There and He Is Not Silent, p. 324, Crossway Books, Illinois, 1982. Return to text.

- Enns, Paul, Moody Handbook of Theology, p. 310, Moody Press, Chicago, 1989. Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon entry for the Greek word for sin, ἁμαρτάνω (hamartanō), the normal NT word for sin, says, “1. to miss, miss the mark, hence 2. Generally, to fail of doing, fail of one’s purpose, go wrong: to be deprived of a thing, lose it.” Simon Wallenberg Press, 2007. Return to text.

- This section is adapted and abbreviated with permission from Dr Alex Smith, author of A Christian’s Pocket Guide to Buddhism, pp. 69–76, Chapter 7, Sharing the Gospel, Christian Focus Publications, Scotland, 2009. The whole book is recommended reading for everyone concerned with evangelizing Buddhists. Available from OMF International offices, worldwide. Return to text.

- Ref. 31, pp. 77–94, Chapter 8, Approaches to Sharing the Gospel. This chapter is essential reading for everyone concerned with evangelizing Buddhists. Return to text.

- Ref. 31, p. 94. Return to text.

- Smith, H.B., Cosmic and universal death from Adam’s Fall: an exegesis of Romans 8:19–23a, J. Creation 21(1):75–85, 2007; creation.com/romans8. Return to text.