历史显示

杜鲁门 是位有思考的果敢的政治家, 有勇气,有决断, 有担当。

麦克阿瑟 是位纯军事而无大局的司令官。

解除麦克阿瑟的军职,不是 杜鲁门一人的心血来潮茫然决定, 参谋长联席会议,陆海空三军的主帅,都支持总统总司令的决定, 也可以说,是三军参谋长的决定由总统来宣布下达和执行。

麦克阿瑟 认为中国和军队不堪一击,主张战火连中国 一起烧, 杜鲁门和他的参谋长们,认为要打一次 有限战争,不要挑起第三次世界大战。而且 麦克阿瑟 几次公开批评杜鲁门总统的国际政策和方针。这惹恼了本来就对麦克阿瑟不感冒的 总统 杜鲁门。

A dispute between President Harry S. Truman and General Douglas MacArthur in 1951, during the Korean War. MacArthur, who commanded the troops of the United Nations, wanted to use American air power to attack the People's Republic of China.

The President, suspecting MacArthur might see that his days were numbered and resign before he could act, moved quickly, announcing the dismissal at 1 a.m. on April 11, 1951:

“With deep regret, I have concluded that General of the Army Douglas MacArthur is unable to give his wholehearted support to the policies of the United States Government . . . military commanders must be governed by the policies and directives issued to them in the manner provided by our laws and Constitution. . . . General MacArthur’s place in history as one of our greatest commanders is fully established.”

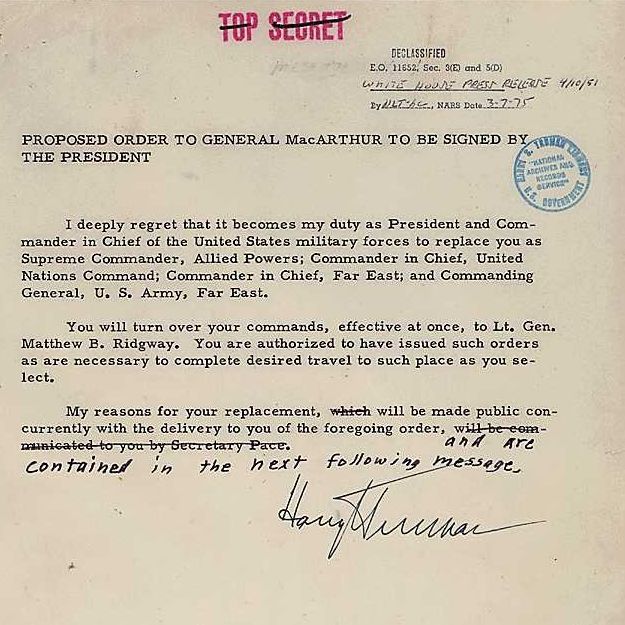

杜鲁门签署的 解职命令原文

In perhaps the most famous civilian-military confrontation in the history of the United States, President Harry S. Truman relieves General Douglas MacArthur of command of the U.S. forces in Korea. The firing of MacArthur set off a brief uproar among the American public, but Truman remained committed to keeping the conflict in Korea a “limited war.”

Problems with the flamboyant and egotistical General MacArthur had been brewing for months. In the early days of the war in Korea (which began in June 1950), the general had devised some brilliant strategies and military maneuvers that helped save South Korea from falling to the invading forces of communist North Korea. As U.S. and United Nations forces turned the tide of battle in Korea, MacArthur argued for a policy of pushing into North Korea to completely defeat the communist forces. Truman went along with this plan, but worried that the communist government of the People’s Republic of China might take the invasion as a hostile act and intervene in the conflict. In October 1950, MacArthur met with Truman and assured him that the chances of a Chinese intervention were slim. Then, in November and December 1950, hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops crossed into North Korea and flung themselves against the American lines, driving the U.S. troops back into South Korea. MacArthur then asked for permission to bomb communist China and use Nationalist Chinese forces from Taiwan against the People’s Republic of China. Truman flatly refused these requests and a very public argument began to develop between the two men.

In April 1951, President Truman fired MacArthur and replaced him with Gen. Matthew Ridgeway. On April 11, Truman addressed the nation and explained his actions. He began by defending his overall policy in Korea, declaring, “It is right for us to be in Korea.” He excoriated the “communists in the Kremlin [who] are engaged in a monstrous conspiracy to stamp out freedom all over the world.” Nevertheless, he explained, it “would be wrong—tragically wrong—for us to take the initiative in extending the war… Our aim is to avoid the spread of the conflict.” The president continued, “I believe that we must try to limit the war to Korea for these vital reasons: To make sure that the precious lives of our fighting men are not wasted; to see that the security of our country and the free world is not needlessly jeopardized; and to prevent a third world war.” General MacArthur had been fired “so that there would be no doubt or confusion as to the real purpose and aim of our policy.”

MacArthur returned to the United States to a hero’s welcome. Parades were held in his honor, and he was asked to speak before Congress (where he gave his famous “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away” speech). Public opinion was strongly against Truman’s actions, but the president stuck to his decision without regret or apology. Eventually, MacArthur did “just fade away,” and the American people began to understand that his policies and recommendations might have led to a massively expanded war in Asia. Though the concept of a “limited war,” as opposed to the traditional American policy of unconditional victory, was new and initially unsettling to many Americans, the idea came to define the U.S. Cold War military strategy.

In 1985 Richard Nixon recalled discussing the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with MacArthur:

MacArthur once spoke to me very eloquently about it, pacing the floor of his apartment in the Waldorf. He thought it a tragedy the bomb was ever exploded. MacArthur believed that the same restrictions ought to apply to atomic weapons as to conventional weapons, that the military objective should always be limited damage to noncombatants... MacArthur, you see, was a soldier. He believed in using force only against military targets, and that is why the nuclear thing turned him off, which I think speaks well of him.

|